Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/07/22/openstack_cloud_controller_turns_three/

Happy third birthday, OpenStack: Ready to dominate all clouds now?

'A testament to the power of bourbon and unit test coverage'

Posted in SaaS, 22nd July 2013 16:56 GMT

It has been three years since the techies at NASA and Rackspace Hosting mashed up their respective cloudy compute and storage software to create OpenStack.

And by most objective measures, the resulting cloud control freak has gained enough momentum - both in terms of partner and developer enthusiasm and the increasing sophistication of its code - to bypass Eucalyptus and CloudStack. It has been fighting against the two older open source alternatives for years, but now it looks like it is close to claiming the much-desired title of "the Linux of cloud operating systems".

OpenStack has come far very fast, and naturally elicits comparisons to Linux itself, which took the enterprise computing market by storm in the late 1990s, first in technical and high performance computing and then among enterprises at large, as a cost-effective alternative to Unix and proprietary operating systems.

Linux now drives about a quarter of server revenues each year and has eclipsed Unix as the main alternative to Microsoft's Windows Server platform. The familiarity that most businesses have with Windows on the desktop has been the key driver of Windows in the data center, much as the similarity between Linux and Unix has been a key driver of Linux systems sales.

In the cloud controller space, there are no such incumbents, although there are natural affinities between operating systems, hypervisors, and now cloud controllers. So few true clouds have actually been built to date (although some of them are certainly large, such as those puffed up by Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, Google, and Rackspace) that the market is still, to a certain extent, wide open.

The market for private clouds is particularly wide open, while that for public clouds is dominated by Linux and either Xen or KVM hypervisors with the exception of Microsoft Azure, which is based on an amalgam of the Hyper-V hypervisor, Windows Server, and System Center with some other goodies thrown in.

Some companies want one throat to choke, while others want the most openness and flexibility they can get. If you can have both, it would be ideal. But that's not how the IT industry works, now is it?

The OpenStack stack community still has a tremendous amount of work to do, and competing cloud platforms (at both the infrastructure layer and higher up in the platform layer in some cases) are not sitting still in terms of development and driving customer adoption.

But as OpenStack turns three, the community can certainly be proud of the fact that NASA and Rackspace managed to get this thing off the ground and, despite much grousing over Rackspace having too tight a hold on the project for the first two years, managing to place it in the hands of an independent foundation that is steering its development. Well, as much as anyone can be said to be steering a collective of open source projects.

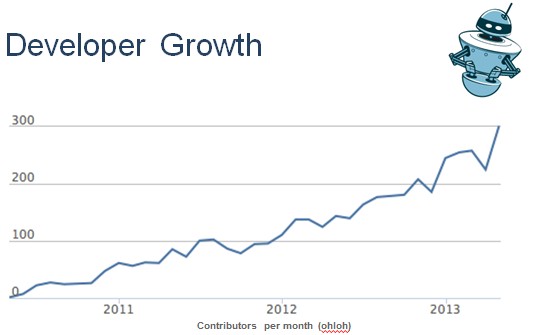

The number of cumulative OpenStack developers continues to grow

"It has been three years that we could never have predicted, with just incredible growth and involvement from way more people than we ever expected," says Jonathan Bryce, executive director at the OpenStack Foundation, which controls the governance for the project.

Bryce told El Reg: "There have been some interesting criticisms along the way, but to me the thing that just really blow my mind is the people who have stepped up and volunteered to be part of the OpenStack community."

The official birthday celebration for OpenStack will take place in Portland on July 24, but there will be over 40 community birthday parties hosted around the world to commemorate the passing into year four for the cloud control freak.

Any excuse to drink, really. That may not be much of an exaggeration, either.

"The fact that we get along at all is a testament to the power of bourbon," explains Josh McKenty, CTO and co-founder of Piston Cloud. Piston Cloud is one of the several distributors of commercial-grade OpenStack support and McKenty was one of the chief techies at NASA who worked on the original Eucalyptus deployments for the space agency. He also worked on the Nova controller that NASA contributed to the OpenStack cause.

"The culture of OpenStack was dominated by drinking and unit test coverage," says McKenty. "The OpenStack Summit is basically Thanksgiving dinner. We have a couple of crazy uncles, people making inappropriate comments, others taking their clothes off. It really is Thanksgiving dinner."

That sure sounds a lot less boring than working for Microsoft or VMware. And, as Bryce explains, it has been edgy from Day One when Rackspace first started pondering what it might do in conjunction with NASA to try to create a pure open source cloud controller. OpenStack is now a genuine contender against Eucalyptus, which has some core components as closed source; Cloud.com, which has since been opened up by Citrix Systems under an Apache license; and VMware's vCloud cloud. The VMWare offering is an extension to its vSphere server virtualization suite - it adds orchestration, metering, and other features to turn it into a cloud.

Amazon ... schmamazon

The fact that OpenStack, unlike Eucalyptus and CloudStack, is not concerned with API compatibility with Amazon Web Services, was a big deal, and one that could have been a problem - and still might be in the future, depending on how dominant AWS becomes in cloud computing. (More on this in a minute.)

"I was at Rackspace when we launched this, and this was something that we had to go to the board of directors to get approval for because we were going to be giving away a lot of intellectual property as a public company," says Bryce.

"And the question, after they had gotten comfortable a bit with the idea, which took some time, that they asked us was this: 'What is the biggest risk? What could go wrong?' And I said that the worst-case scenario is that we go through all the trouble of making our code public and trying to do development in the open and nobody else shows up."

Bring a bottle - and your code contribution

Well, people showed up to the OpenStack party. As of this week, the OpenStack community has 10,149 members from 120 different countries. And 1,036 of these have made more than 70,137 different code contributions since the OpenStack project was launched three years ago.

Not everyone stays active in any community forever, of course, and the OpenStack Foundation estimates that there are around 240 or so active contributors to the code base in any given month and that over the course of a release cycle there are around 800 to 900 active contributors. This, by any measure, is a large-scale software project.

"OpenStack has a diversity of use and a diversity of community," says McKenty, and this is its strength. "And the fact that OpenStack is past 10,000 members and that it has more than 1,000 active code contributors is astounding.

"More than 10 per cent of community members are actually successfully landing contributions to the code. If you compare that to Mozilla and the work on Firefox, which I was also part of, there were in the low hundreds of people who landed code on Firefox, and their community was hundreds of thousands of people. So the ratio for OpenStack is just amazing."

In the past three years, OpenStack has been beefed up from its initial Nova compute controller from NASA and Swift object storage controller from Rackspace to have additional modules to add network virtualization, bare metal provisioning, virtual machine image management, block storage, access control, and a graphical management console, just to name a few.

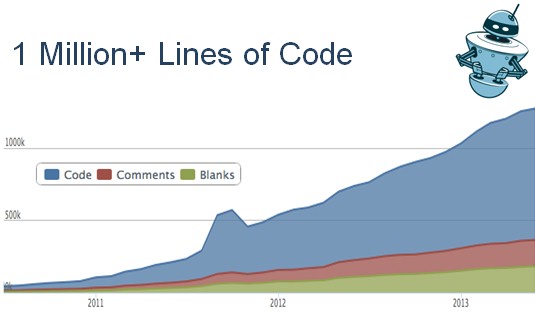

More modules will be added as features roll into existing modules. At the moment, the official OpenStack collection is comprised of just under 1.3 million lines of code, and as you can see, the code base has grown fast as features and modules have been added:

Yes, they count blanks and comments as well as lines of code

This chart above shows how the code base for OpenStack has grown over time as each successive release has been outlined and then coded, but what it does not show is the code churn, which is substantial.

For instance, in the last 12 months, the OpenStack project has added 2,936,791 lines of code, but has removed 1,594,506 lines of code. This is still software that is rapidly changing, even as the current "Grizzly" release, announced in April, is arguably the first production-grade implementation of OpenStack that bleeding edge companies can think of deploying in their data centers to build a private cloud or a public cloud (if they are service providers).

It is hard to say if the code base will settle down. As long as the code is improving and OpenStack doesn't break API compatibility, most people won't care or even notice.

"Ultimately, we focused on creating an environment where everybody who wanted to come pitch in and work on this could have an impact, could find a place, and have an effect on OpenStack and therefore on the future of computing," says Bryce.

El Reg tried to goad Bryce into saying even if they are VMware with much taunting, but the most we could get Bryce to say was "even if they are a large, proprietary software company."

"The other thing that is great about this is that OpenStack has forced a number of companies to take a more open approach in how they do development and licensing and how they interact with partners," Bryce continues.

"Again, if you go back three years, everything was not using an Apache license and there were a lot of open-core projects out there. OpenStack was started by users, not by software companies who were trying to do this balancing act of being a software company and making money off some of the software and giving away other parts. By not having that built-in conflict of interest, it freed us up to try to make OpenStack the most open community it could possibly be."

The inevitable criticism and sour grapes

None of this means that there has not been plenty of criticism heaped on OpenStack software, the foundation that controls it, and the developers who code it.

"The older OpenStack gets, the more I feel like a parent, and I have two kids of my own outside of OpenStack," McKenty says with a laugh. "It is amazing that everyone who is not a parent wants to tell you how to raise your kid. Every single person will criticize what you are doing because it is not their job.

"So this week has been punctuated by 'You're doing it wrong.' And they can't agree on what we are doing wrong, which is what makes this funny. Maybe I am just a parent who feels this criticism personally."

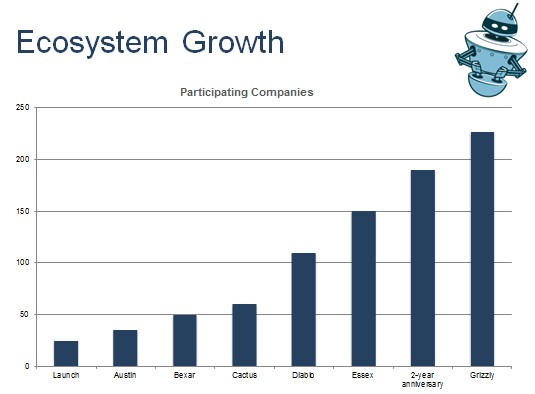

The OpenStack ecosystem of partners continues to expand

The criticism comes from two camps. There are those who are looking for "the POSIX of the cloud" and accuse the OpenStack Foundation of not creating this, which essentially means not making OpenStack a cloud computing standards body instead of product development community.

"A standard is not a product, and it is not even a framework," continues McKenty, and he is on a roll now. "Moreover, the best standards we have ever had were the Internet standards, and the entire Internet RFC process was about taking what was already working and then calling it a standard, not sitting around in a committee four or five years ahead of time inventing something in the abstract.

"And that is specifically what we refuse to do – which is to make stuff up before we build it – with OpenStack. The people who really like to be on those committees are really offended because we don't give them a place to live."

You're not... compatible

The other criticism is that OpenStack should have just cloned Amazon Web Services, and McKenty is having none of that talk.

"This one makes me crazy," says McKenty. "The reason that people wanted something like OpenStack to exist is because they wanted something that Amazon could not deliver. And the example I always give is the first reason we broke AWS API compatibility is because we wanted to be able to have an instance that you could turn off and then you could turn it back on.

"You cannot do that with Amazon. If you turn it off, it is deleted, it is destroyed. Goodbye. Sayonara. Having AMI images you can reload is not the same thing as having a pause button."

The other problem with strict AWS compatibility is that OpenStack is meant to be used in private, public, and hybrid clouds and there will be certain APIs that have to be exposed that do things that AWS simply does not expose externally (even if it might have such functions internally).

The example that McKenty gives is that the corporate auditors have to know the physical location of a VM, and there needs to be an audit trail of where is has been running as it flits around the cluster of servers inside the firewall or hops back and forth between public and private clouds.

The dominance of Rackspace over OpenStack

The whole point of starting OpenStack as far as NASA was concerned was to get the space agency out of the software development business yet give it a cloud controller that was totally open source and that it could contribute to as a means of getting the features it needed. As soon as NASA's cloud coders left to do their own riffs on OpenStack, that left Rackspace in the driver's seat as the biggest contributor and at this point the largest user of OpenStack.

With the establishment of the OpenStack Foundation last September, Rackspace let go of OpenStack and it was then that Red Hat could join up and formally adopt OpenStack as its official cloud control freak for peddling to its Linux shops.

IBM followed suit and is now adopting OpenStack as its cloud controller for both private clouds built from its systems (including System z mainframes, believe it or not) and for its SmartCloud Enterprise public cloud.

"Rackspace is consciously not worrying about whether we are the top contributor in terms of commits to a release of OpenStack, and we are looking at other things such as patches," explains John Igoe, vice president of cloud at Rackspace. "We are also looking at what important projects, from an operational standpoint, that should be started up."

Don't fork this up, man...

Igoe has been involved with OpenStack even before the project was formally started, having spent time with Rackspace executives four years ago when he worked at Dell's Data Center Solutions custom server business. Igoe ran a company called Silverback that created remote network monitoring and management software that was bought by Dell.

He was eventually tapped to handle the software part of this unit, and among other things, he shepherded the creation of Dell's "Crowbar" OpenStack setup utility and became the point person at Dell for hooking into the OpenStack community. Three months ago he joined Rackspace, and it looks like he is eager to assert himself, on behalf of his new employer, inside the OpenStack community. This will probably annoy other contributors and member companies.

"I think Rackspace, since it has transitioned the ownership and the management of OpenStack to the foundation, an independent entity, is in the process of reasserting its leadership position in the community," Igoe tells El Reg.

"What I saw when Rackspace was the major sponsor of the foundation was a little bit of timidness on the part of Rackspace to actually to lead and demonstrate a direction in the community. I think that what we will see in year four is that Rackspace is going to be much more visible. And that is important because the OpenStack Foundation board is facing a number of challenges."

The first challenge is that users are becoming an important part of the community along with developers and corporate sponsors, and their needs have to be addressed. So, for instance, there needs to be a shift from features and functionality being added to making OpenStack a better operational tool, making metering, billing, orchestration work better. And this is something Rackspace execs involved in OpenStack have been saying for the past year.

But Rackspace is also quite aware that it cannot push OpenStack too hard and that it is not in charge of the project any more.

"We need competition in the OpenStack community, and we need cooperation, too," says Igoe. "If we don't encourage competition and really solid collaboration, we are going to develop forks.

"Organizations are going to feel that in order to drive their business and a return on their investment, there will be forks in the OpenStack community where people try to differentiate themselves based on proprietary capability. And that will not be good for the overall growth of OpenStack."

That is always the challenge with any open source project. And only time will tell if OpenStack can hold it all together. Perhaps it is best to just keep the bourbon flowing, then. ®