Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/06/28/30_years_on_the_story_of_the_memotech_mtx/

30 years on: Remembering the Memotech MTX 500

Very possibly the second-best British micro of the early 1980s

Posted in Personal Tech, 28th June 2013 13:04 GMT

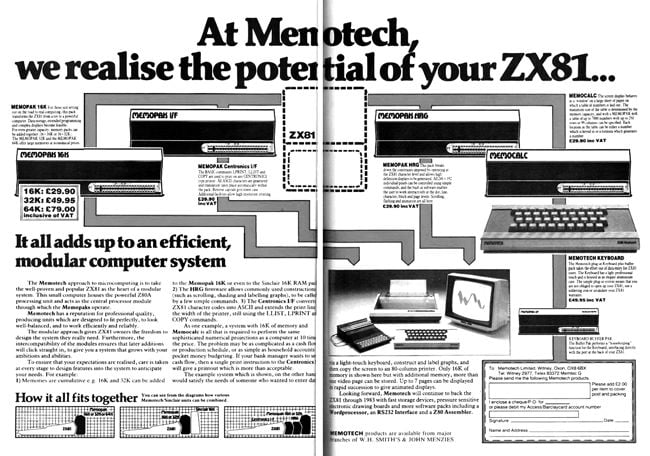

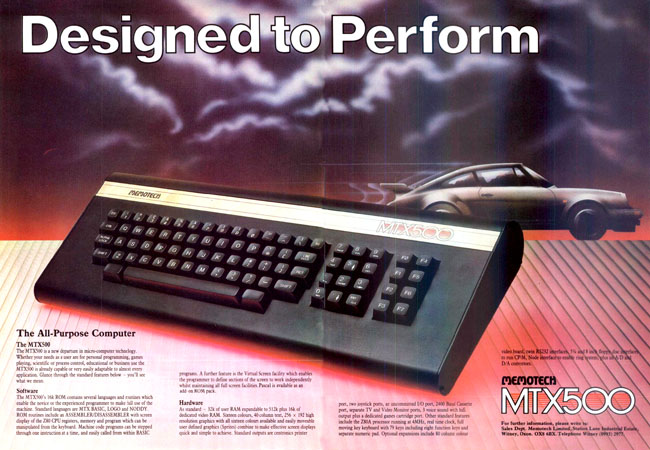

Archaeologic Memotech liked to advertise its MTX 500 and 512 microcomputers with a picture of a speeding black Porsche, but the machines, which made their first public appearance 30 years ago this month, while undoubtedly quick off the mark soon slammed hard into an unforeseen wall thrown up by a sudden, severe change in market conditions.

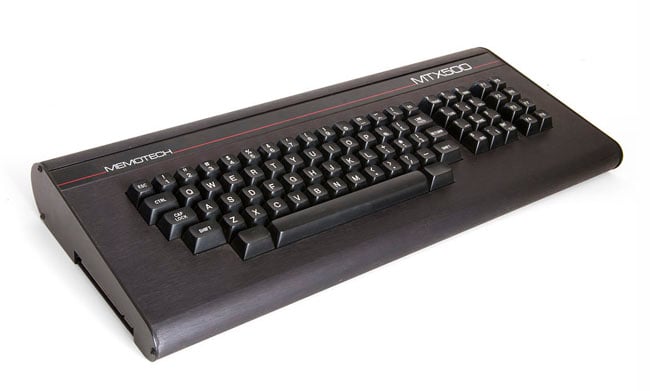

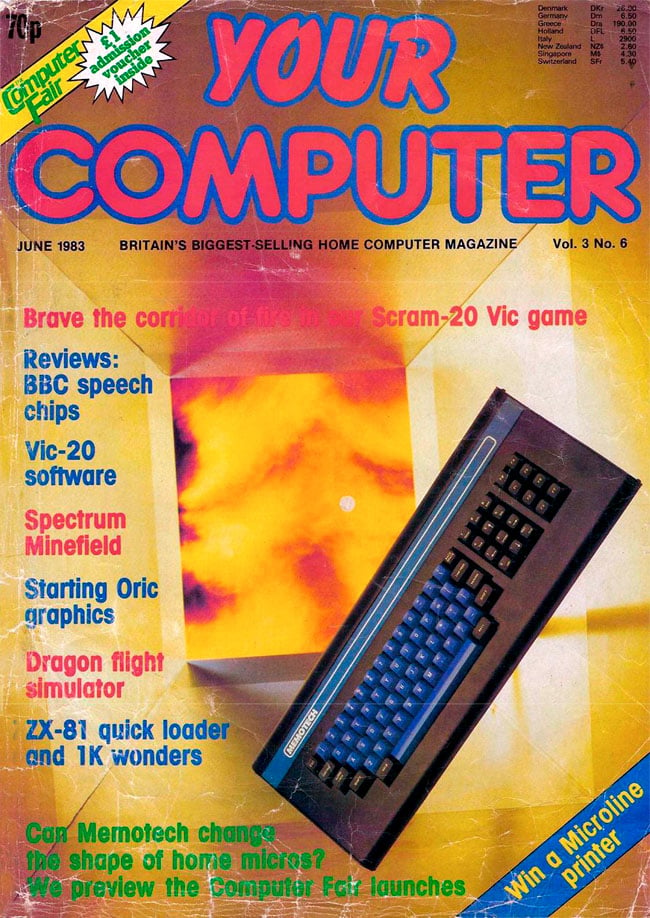

Announced in June 1983 at the Earl’s Court Computer Fair and at the height of the UK home computer boom, the MTX almost immediately won plaudits for its build quality, performance, capacity and all the functionality its developers had crammed in. Only slightly more expensive than a Sinclair ZX Spectrum, the MTX nonetheless had a spec to match that of the BBC Model B. It ought to have been of one the defining micros of the third generation of British home computers, but the near-complete collapse in demand after Christmas 1983 which killed the likes of Dragon Data, Camputers and others, would prevent it ever realising its full potential.

The MTX 500

Source: Bilby

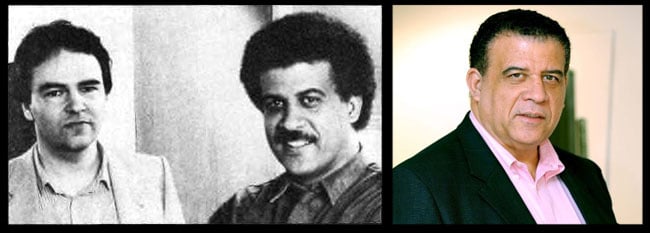

Memotech was the brainchild of two Oxford boffins: a mathematician and a metallurgist, Robert Branton and Geoff Boyd.

During the mid-1970s, Boyd studied for his PhD in Oxford University’s Department of Metallurgy. There he’d had to design electronic circuits for lab work, and quickly discovered he was a rather dab hand at it. Becoming something of an electronics enthusiast, he was soon building audio kit at home.

Around 1977, Boyd met Branton, who was then working within Oxford’s programming research group. Boyd recalls encountering his soon-to-be business partner at a ‘crammers’ session in which the two, and others, were giving extra tuition to school kids getting ready to take their A level exams. The two became friends, and when, in 1979, Boyd moved to the University’s Engineering Department to begin his post-doctorate research work and his electronics projects shifted toward more complex computing circuits, the pair decided to go into business.

Boyd recalls their first work: a touch interface system, devised and designed out of hours - the two men were still in their day-jobs at the University - as a successor to the the Qwerty keyboard. “It was customisable. It would have readers on it - you just slipped a bit of paper in and convert it from, say, a keyboard into map reading device, and that’s really where we started.”

Enter the ZX81

Branton was the software guy, Boyd the hardware man. The two found backers to provide the finance, and a company was formed, Oxford Computing, to produce and market the gadget. It wasn’t, Boyd recalls, an ideal experience - he feels the backers got rather more out of it than he and Branton did - so the two men quit and began to seek out a new project on which to work.

And then, in March 1981, Sinclair Research launched the ZX81. “The thing that was crucially different about the ZX81 was that it was the first small computer with floating point arithmetic. Because we were both scientists, that made a huge difference in terms of what it could do. And that’s why we got involved. We probably bought one of the very first ones, in kit form.” But the machine had just 1KB of memory, and the two partners realised that users were going to need a lot more.

Boyd says he was very interested in memory at the time, having designed the memory sub-system for the digitiser. He used that as the basis for an additional memory unit for their ZX81, and so was born the first product they could make and sell rather than license. Memotech was formed, and their efforts yielded some of the first memory expansion modules for the Sinclair machine, along with Centronics and RS232 printer interfaces, and a typewriter-style keyboard, connected through the ZX81’s expansion port, for quick-fingered coders to use in place of the Sinclair-standard membrane job. The HRG masked 2KB of the ZX81’s Rom with firmware of Memotech’s own to add 248 x 192 hi-res graphics, in conjunction with Memotech Ram expansion.

The company didn’t just offer hardware. Branton’s software skills were put to work producing spreadsheet and word processing applications.

Memotech’s add-ons business was a huge success, and the company grew very rapidly indeed, especially when Sinclair’s own ZX81 Ram Packs were in short supply and, later, when Timex, Sinclair’s contract manufacturer, launched the ZX81 in the States under its own name.

“When Dram ICs were purchased, they needed to be fully tested... which typically lasted three to four minutes,” recalls Boyd. “In the UK, there were two contract manufactures who made Sinclair’s add-on packs: Thorn EMI and AB Electronics. They used GenRad testing machines that cost over $1 million each. You couldn’t speed up the test, so the throughput of these machines was limited.

“Memotech couldn’t afford these machines to test its Memopaks, as they were called, so we built our own testing rigs using Intel 8048 8-bit microcontrollers with a complete memory test system that cost us less than $500!”

Move to micro

Clever applications of technology like this, and the surging interested in the new home computers, helped Memotech became a million pound business within a year of its 1981 foundation. By 1984, it had sold more than a quarter of a million MemoPaks and grown its headcount to 110. Boyd had long since left the university life behind to work solely for on his new company as Technical Director.

Boyd and Branton might have contined to focus on peripherals, but the announcement in April 1982 of the 48KB Sinclair Spectrum prompted their backers to wonder whether, with computers coming out with ever more memory on board, there was any long-term future in the memory add-on business. At the first sign of success, Memotech had bought land in Witney, Oxfordshire on which to build a factory to punch out even more of its anodised aluminium-clad memory packs. If the add-on market was about to die, they needed to come up quickly with something else the plant could be used to produce. Boyd and Branton were told toward the end of 1982 that it was time they got into the micro business themselves.

Fortunately, they already had a foot in the door. That year, the Memotech founders decided to fund a project to build a low-cost computer-based hi-res video digitisation system, dubbed HRX. The system was being designed by two post-graduate electronics engineers, Steve Marchant and Chris Marvell. At the heart of the HRX design was a 6MHz Z80B-based computer built by Marchant, which he called, unsurprisingly, the SM1. It had 64KB of Ram, a pair of 8-inch floppy drives, a full 80-column colour graphics card and ran Digital Research’s CP/M operating system.

Memotech never sold the SM1, though a fair few were built to use as development machines within the company and it did, later, offer the HRX. Memotech might have chosen to mass-produce the SM1 - business-centric CP/M machines were much in demand even two years after the 1981 debut of the IBM PC - but because the company had very close partnerships with major retailers and the home computing resale channel, it was decided to develop a system for the home derived from the SM1.

“By that time we had deals with all the top distributors, with WHSmith, Boots and so on, and we figured we just needed to make a great-looking computer and put it on the market and it would sell like hot cakes,” says Boyd now. And, indeed, as work on the new micro progressed through the first half of 1983, it seemed that whatever computer companies could come up with, British buyers would snap straight up.

The result was the MTX. Marchant himself didn’t work on the machine, though Boyd is emphatic about the debt the MTX owes to Marchant as the creator of the SM1. Essentially, Boyd took Marchant’s design and subtracted the more costly and business-centric components to bring it to what Boyd said in an interview with Popular Computing Weekly in June 1983 was “the minimum entry point”. Adds Boyd today: “Most people if they design a computer, design from the bottom up. We designed the MTX from the top down. Our task, in January 1983, was to see how we could take that great design and design it down to an entry-level system.” Marchant’s work on the SM1 allowed Boyd to complete the MTX hardware very quickly.

Enter the MTX

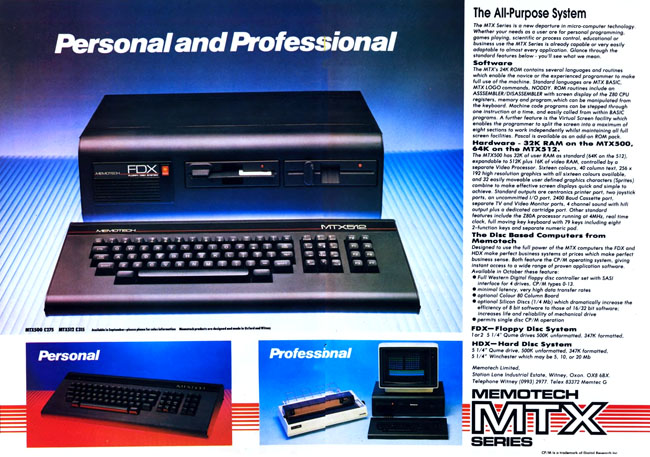

Not too low-end, mind. The MTX was always designed to compete more with the then recently released BBC Micro than the Sinclair machines, now including the Spectrum, that Memotech had cut its teeth producing peripherals for. “We are aiming at the more serious home user and the business market,” said Memotech sales and marketing chief Tim Spencer in 1984. “The machines are not aimed at the games market, although of course you can play all the usual games on them.”

The MTX wasn’t simply an SM1 without the disks and disk operating system. Any home computer released back then needed a built-in programming language, sound and colour graphics, and the hardware and software to support these needed to added to the pared-back SM1 design. So too was TV output and, in a nod to the Sinclair end of the market, joystick ports. That said, Boyd put in all the hooks he could to ensure the MTX could easily be upgraded back to the level of the SM1, which was also the basis for all the major peripherals Memotech would offer for the MTX.

The MTX500, then, used a 4MHz Z80A backed with just 48KB of Ram. A version with 96KB, the MTX512, arrived early in 1984, but both machines could be expanded internally to 512KB - hence the latter’s name, and alluded to broadly in the name of the first model.

The MTX’s Basic was stored in 24KB of Rom, implemented in three 8KB Rom chips, but more could be added through the expansion edge-connectors placed at either end of the motherboard. Up to 48KB could be added this way, with the contents paged in and out as necessary and in a way transparent to the user. Likewise the all the extra memory beyond 64KB that was all the Z80’s 16-bit addressing could reach at any given time. Boyd had made much of the Z80’s ability to used paged memory in developing his ZX81 expansion packs, which supplied the CPU with their own Ram and Rom selection signals, and used the same trick with the MTX. He tucked the control circuitry in a tiny ULA to keep its secrets safe.

Your Computer puts the prototype MTX 500 on its June cover

The right-side expansion connector was reserved for the MTX Communications Board, which added a couple of of RS-232 ports to be used to hook up the computer’s FDX and HDX storage peripherals, and to connect the MTX to Memotech’s Oxford Ring networking system - a nod to Acorn’s similar network, Cambridge Ring. The left-side connector was presented as a general purpose expansion port, accessed by removing a plastic cover on the side of the MTX’s casing.

The MTX had a 40 x 24 alphanumeric display; Boyd had hoped to squeeze in 80-column graphics, but couldn’t get it to fit in the time allowed to develop the machine. The computer also had a low-res 64 x 48, 16-colour mode that allowed any of the colours to be applied to any of the 4 x 4 pixel blocks; and two 256 x 192 hi-res mode which could also present text on a 32 x 24 grid. In the first of these modes, you could apply two colours to each 8 x 8 array of pixels. The second mode allowed 16 colours to be used. In each machine, 16KB of memory was reserved for the video buffer, and kept entirely separate from the program Ram, allowing users to switch to the higher resolutions without losing space for code.

Stylish design

The picture was managed by the Texas Instruments TMS9929A video chip used in the machine - “the best low-cost graphics chip available”, says Boyd - as was the support for up to 32 user-definable 8 x 8 or 16 x 16 pixel sprites, which, unlike the Commodore 64, could be defined and manipulated with the built-in MTX Basic.

Alas the MTX couldn’t do circles, which appeared as ovals, as they did on the Oric. But it had one clever, unique trick: one of the 16 colours was "transparent" which, coupled with the MTX’s virtual screen system, could allow a background image to be displayed through a "window" in the foreground image.

Brushed metal

Sound was provided by a second TI chip, the SN76489, this one able to drive three channels of tones and a fourth for noise. It was the chip the BBC Micro used.

The MTX’s anodised black aluminium casing packed in the inevitable TV modulator output plus a co-ax monitor connector; a pair of D-sub, Atari- and Commodore-style joystick ports; 3.5mm mic and ear sockets for the fast, 2400 baud cassette feed; an RCA sound port for hooking the MTX up to a hi-fi; a Centronics parallel printer port; and two gaps for the pair of extended D-sub RS232 ports that were a feature of the Communications Board. The joysticks operated by emulating arrow key presses, so they didn’t need special support in software.

All this in a low-rise shell which, with its integrated 59-key keyboard, and separate numeric and eight-button function key pads - 79 keys in all - could easily be mistaken for a business PC keyboard, especially when hooked up and placed in front of Memotech’s dual-floppy unit, the FDX, or its hard drive enclosure, the HDX.

Coming as the MTX did from the SM1, it was decided very early on that it would measure up to the de facto standard width of a business computer, 475mm, and that it would be clad in Memotech’s trademark black anodised aluminium. The extra numeric keypad and function keys were added because the Qwerty deck alone looked lost among the acres of metal.

The metal casing had other, less aesthetic benefits: it operated as a heat sink - the voltage regulators were bolted to the case metal - and became a Faraday Cage to block stray radio interference from the MTX’s chippery. “Unlike some of its competitors, the MTX512 sailed through the stringent American FCC approval procedures with flying colours - the first time round,” Memotech boasted in its ads.

Development days

The MTX case’s physical attributes were established early on, but its colour scheme went through several incarnations before the machine went into full-scale production. Early, pre-release versions sported bright blue Qwerty keycaps and branding - presumably to go with the white on blue text screen the computer presented when powered up and connected to a TV. The adverts which began to appear in the summer of 1983 had red and white branding, with the original Memotech logo. Finally, Memotech settled on the familiar red highlighting, white lettering and all-black keycaps.

Some photos from the period show an MTX with a stronger red colour scheme, not just the branding but also full red keycaps for the keys that weren’t part of the main alphanumerical set. This, in fact, was one of the special versions developed to win a massive order from the Russian government.

The deal with the Soviets was a couple of years further on from the MTX’s first appearance in June 1983. Having commenced development work in January 1983, Boyd recalls, the first working prototype was ready in February - on Valentine’s Day, says Boyd, a target set at a preliminary meeting between him and Branton on Boxing Day 1982. The following months were spent devising how how the MTX’s case would be cut, and in the development of MTX Basic and the machine’s other firmware, including its machine code monitor and Pilot-like computer-assisted instruction language, Noddy - a series of “interactive screen manipulation routines”, as the manual put it.

“Robert took on Richard Hammersley, who was a student at Imperial College, and between him, Robert and another developer, John Luscombe, they were able to do the software, while I tested it,” remembers Boyd. “We had to go from January to launch a product which was ready in six months, and it had to be bug free because it had to go to Rom which had an eight-week lead time so you had to get it right first time. We achieved that, the four of us.”

Other folk had smaller roles. Oxford mathematician Richard Pinch, who knew Boyd, was asked to provide an algorithm to underpin MTX Basic’s ARCTAN command, though the implementation of his suggestion proved not as accurate as it should have been, which affected some of the MTX’s benchmark scores. These were generally better than all other home micros other than the BBC Model B, which cost £124 more and had less memory, though slightly better connectivity options.

When the MTX debuted, Memotech said the MTX would ship in August, but it would be much later in the year before production began, when “the company’s high-profile advertising campaign has been titillating potential buyers for many months”, as What Micro? put it, and full-scale output wouldn’t begin to take place until early in 1984. During this time, Boyd, Branton and co. had moved on to focus on the development of the FDX and other peripherals, leaving the MTX in the hands of colleagues responsible for manufacturing and sales. They also established Continental Software, run by Ed Hollingshead, to create software for the new machine.

Positive reviews

By the end of 1983, review samples had already trickled out, first of the MTX 500 and then, toward the end of 1983, of the MTX 512. Naturally, reviewers focused on the look of the MTX. “The MTX 512 is a real looker,” wrote John J Anderson in US magazine Creative Computing. “It is a computer capable of looking as ‘at home’ in your living room as your stereo does... Feels good too, like slamming the door on an XJ6.”

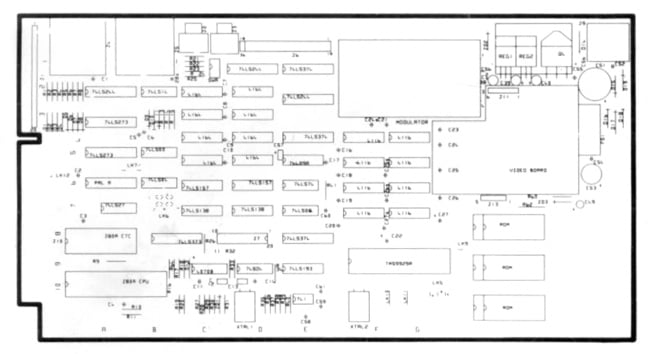

Your Computer called it “striking”, but Digital and Micro Electronics’ Dick Leslie was more pragmatic: “Assembly is extremely rigid,” he wrote and noted how a small allen key could be used to remove the unit’s end caps, allowing the upper surface to be lifted up to reveal a well-organised motherboard: “All the components are laid out neatly and without any space being wasted... There are no signs of any last-minute alterations on the boards... There isn’t a ULA in sight, which perhaps explains why there have been no serious delays in getting this micro into the market place.”

Leslie even pointed out that a daughtercard was not a patch for motherboard bugs, as was usually the case with early 1980s UK micros, but a swappable unit holding all the country-specific video circuitry.

Inside the MTX 512: note the space for the Communications Board on the right side and the country specific video circuitry daughtercard. The Z80A is down in the left hand corner

Click for a larger image

Source: Dave Stevenson

“The keyboard is superb - goodness knows how much it is costing Memotech to fit it - and it gives the machine a very definite professional style,” Leslie added.

Other reviewers praised the MTX keyboard too - the keys “have a professional and solid feel and a touch typists would feel at home with them”, noted Your Computer’s David Aubrey Jones - though almost every reviewer disapproved of the undersized Return key.

What Micro? was also bothered by the two unmarked keys placed on either side of the spacebar: press both simultaneously and the MTX would perform a reset. The magazine felt this was too easy to do accidentally. “MTX owners would be well advised to consider the old Apple trick of taking the plastic caps off these keys so that they are less prone to accidental use,” it suggested.

But there was plenty of functionality for others to praise, such as the MTX’s virtual screen system. “One can create up to eight of these Virtual Screens with the CRVS command and switch between them with VS,” wrote David Aubrey Jones in Your Computer. “Another command, DST, allows one to roam about freely within screen setting up a page of text using full-screen editing facilities.”

Noddy, meet Basic

Boyd recalls the virtual screen functionality being added because a visitor to Memotech had happened to mention that Microsoft was working on a windowing system, so one of the software team decided to bring a version of it to the MTX. Similar discussions about the Logo computer language and languages for computer-aided learning had led to the addition of Noddy, a text manipulation language for question-and-answer driven programs, and to Logo drawing commands being built into MTX Basic.

Of Noddy, Your Computer wrote: “There are only eight simple commands that need be mastered [INPUT, DISPLAY, RETURN, EXIT, GOTO, COMPARE, PAUSE and OFF] before some quite complex question and answer type program can be written. It is constructed in pages that incorporate text to be printed to the screen.” Not unlike Apple’s HyperCard, in other words, or even Tim Berners-Lee’s early HTML precursor, Enquire.

Borrowing from the Camputers Lynx, MTX Basic implemented a CODE instruction to hold machine code to ensure programmers could augment their Basic software without needing to POKE decimal values READ from a DATA statement into a pre-determined area of Ram. Unlike the Lynx, the MTX had another instruction, ASS, which was used to enter Z80 assembly language statements directly.

The MTX’s assembler was separate from Basic and could also be accessed through the machine’s Front Panel Display, one of the machine’s virtual screens. This presented a source code listing disassembled from memory, the instruction at the current Program Counter reading, register values and memory in hex or Ascii. Code could be executed instruction by instruction, and breakpoints set to aid debugging, all thanks to hooking the Z80’s Non-Maskable Interrupt (NMI) to the timer chip.

It was, in short, a good old-fashioned monitor program - the sort of thing all home computers came with in the 1970s but which fell out of favour when machines began to ship with Basic built in.

“I could recommend no better way to master beginning Z80 assembly,” said Creative Computing’s John J Anderson.

This was a feature other reviewers lauded too, and they were generally very impressed with Memotech’s work. The MTX 500 was, said Your Computer, “a true match for Acorn’s BBC computer... It is well designed and very sturdily constructed. At £275 it is good value when one takes into account what it includes.”

Why 1984 was not like 1983

Computing Today’s Owen Bishop saw the MTX’s graphics capabilities, backed as they were by dedicated Ram, plus the machine’s assembly language support and powerful Basic, scope for the creation of “some extensive and elaborate games”.

But it wasn’t to be. Like so many other early 1980s home micros, the MTX, though undeniably competent and well-priced, nonetheless failed to make a dent in sales of the pricier but in-demand BBC Micro, or those of the cheaper, less sophisticated Sinclair computers. Boyd and Branton found that the distributors and retailers who had gobbled up Memotech’s ZX81 add-ons were decidedly less keen on the company’s micro.

Worse, come early 1984, and suddenly punters seemed a lot less interesting in gobbling up new micros than they had during 1983. Hard enough as it was to compete with the big names, “the bottom fell out of the market,” says Boyd. “No one was buying.”

Having invested so heavily in plant to build ZX81 add-ons and then to convert it into a factory to make computers, Boyd and Branton had to find somewhere else to sell those computers - they weren’t going to sell in the UK. The US was considered, and a US operation established, but such was the colossal cost of marketing there that it could never be a short-term solution. Fortunately, Memotech’s distribution partners in France, Germany and Scandinavia proved more loyal, and as sales trickled out in the UK, demand was strong on the Continent. Indeed, Boyd says this dynamic became apparent very quickly and after a short time the company effectively focused its efforts on supplying its continental partners.

No wonder, then, that in December 1984 when it was summing up the micros available to Brits that - disastrous as it would turn out - Christmas, Personal Computer News said: “If Memotech is guilty of anything, it is hiding its light under a bushel.” Boyd says Memotech continued to advertise in the UK - “it was the centre of the market, you had to maintain a presence” - but its eyes were looking elsewhere.

“The MTX is one of the best-built machines around offering an extremely advanced specification for the price,” continued PCN. “Success in the micro field is an elusive thing but few who have missed deserve it more than Memotech. If they could get more software house to back it the MTX would really take off.”

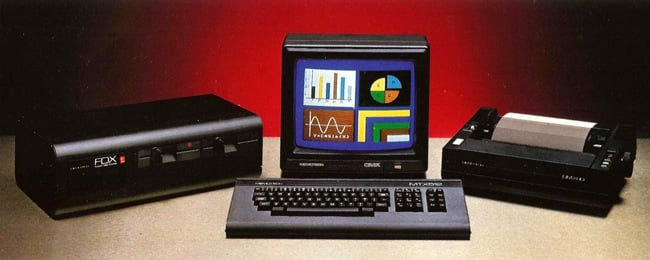

In a bid to boost sales, Memotech cut its UK prices in August 1984, dropping the MTX 500 by £100 to £175 and the 512 to £199. By this point, Dragon Data and Camputers had already gone bust, Oric was wobbling, and even Sinclair and Acorn were feeling the pinch. Memotech was perhaps one of the few vendors to already have had an eye on professional users, and that year it released the FDX and HDX, add-ons to give the MTX business-friendly technology. And the MTX series was briefly joined in the autimn of 1984 by the RS128, an MTX with 128KB of Ram, though there’s little evidence that Memotech shipped and RS128’s any great volume, certainly not in the UK.

Dead not Red

The FDX looked like a 16-bit business micro’s system unit. It gave the MTX a pair of 5.25-inch floppy drives and the 80-column text-centric graphics cards needed to run the copy of Digital Research’s CP/M 2.2 the FDX bundled. Memotech also chucked in SuperCalc 2 and NewWord to handle, respectively, spreadsheet and word processing duties. Hooking up the FDX and starting it all up from a system disk would bypass the MTX’s Basic interpreter and juggle the memory map the way CP/M liked it.

The £870 add-on also contained space within its enclosure for up to four Memotech silicon disks of the kind enigneer Steve Marchant had devised for the SM1 back in 1982. It also had expansion ports for extra drives and such. Indeed, the FDX almost turned the MTX back into the SM1. The HDX was a variant of the FDX, with a 5, 10, 20MB hard disk in place of the second floppy drive.

One problem: business users were now beginning to favour IBM-compatible PCs over CP/M systems. Memotech probably had a window of opportunity to make the most of the last years of CP/M, but it was soon distracted by an opportunity it felt it could not let go by: to sell hundreds of thousands of machine to the Russian government.

The MTX and its FDX (left) add-on were critically acclaimed. Memotech even rebranded a dot-matrix printer to go with them

The company signalled its intentions in April 1985, though the deal-making had been going on for months previously, a result of a 1984 government initiative to bring some help to the UK’s struggling tech companies. PCN reported that the company was anticipating the sale of some 200,000 micros and 20,000 disk drives units to Russia.

The Soviet Union was in the market for computers it could put into its schools. At the time, export controls strictly regulated the shipment of advanced Western computer technology over the Iron Curtain, but COCOM regulations were changed to allow CP/M machines to be sold to the Eastern Bloc. Memotech, with its Z80-based, CP/M capable MTX was an obvious contender, less so Sinclair with its Z80-based Spectrum and Acorn, with the 6502-based BBC’s add-in Z80 option, but they too were introduced to the Russian negotiators.

Meanwhile, Memotech had another trick up its sleeve: Speculator, a gadget allowing MTX owners to play Spectrum games on their computers. Both machines, of course, were based on the same processor, the Z80, so Memotech hired a contract programmer called Tony Brewer to devised a way to load machine code games off tape into the MTX memory - the Speculator shipped with a set of “loader programs” for 20 popular Spectrum games - and run them. Brewer had already written driver code for the FDX’s silicon disks.

Collapse

At the same time, other Memotech programmers were working on the Russian version of the MTX. The Soviets required some cosmetic changes to be made: red instead of black, mainly, but only a couple of demo machines were actually produced, says Boyd. The bulk of the work, however, involved converting MTX Basic into the Russian language. Memotech had some expertise here: the MTX already contained character sets for a variety of European languages, to facilitate sales in France, Germany, Spain and Sweden.

And then the Russian buyers decided instead to acquire just 10,000 computers based on the MSX platform.

Immediately after the announcement of the MSX deal, Memotech spokesman Jeff Wakeford told Popular Computing Weekly: “[The Russians] have asked us to go back to the Soviet Union with the Memotech micros in August, so at least they’re still interested.”

They weren’t, and as MTX sales continued to fall, Memotech’s options were running out. In September 1985, it slashed the price of the MTX 500 to just £79.95, the 512 to £129.95. It was a desperate move and it failed to pay off. As the money ran dry, Memotech had little option but to declare bankruptcy and call in the receiver.

Naturally, the company blamed the Russians, but today Geoff Boyd admits they were simply a convenient scapegoat. What really killed Memotech was developing and producing a machine during a boom - 1983 - only to launch and begin selling it right before a bust - 1984. Failing to persuade retail and distribution giants to buy the MTX as readily as they had Memotech’s memory add-ons didn’t help. Almost all the components needed to manufacture 1984’s machines had been bought in advance during 1983 at the peak of the market. So not only had Memotech stacks of parts, it had also paid a premium for them. It had had to, says Boyd, to secure supply and buy heavily to beat lengthening lead times as factories became jammed with production orders. Besides, not a soul had anticipated 1984’s decline.

By March 1986, Memotech’s backers had decided to move on. Robert Branton had left the company during the 1985 crisis, so Boyd acquired Memotech’s assets himself and prepared to re-launch the company as Memotech Computers. He had help from Keith Hook, who ran SyntaxSoft, which had sold the Speculator and a similar gadget Tony Brewer had worked up for the Tatung Einstein. Something of an MTX fan, Hook also ran Genpat, an MTX User Group and his byline can be found in old issues of PCN as a reviewer and letters-page correspondent.

Memotech reborn

He may even be the real writer of a letter from one Philip Arkley of Acrington, Lancashire published in Popular Computing Weekly’s 14 August 1986 issue, which noted the arrival of both Vortex Software’s Highway Encounter game and that “most of Mastertronics’ best software” had all now come to the MTX courtesy of Syntaxsoft’s porting efforts.

The surprisingly well-informed Arkley also claimed that Memotech Computers had now axed the 500 and slashed the price of the 512 to £79. “For the price of three-quarters of a Spectrum you get four times the speed and power,” he insisted before promising a new machine at Christmas - four months away. It’s hard to believe Arkley was just an ordinary MTX user.

Not least because he was correct. September 1986 press reports suggested Memotech 2.0 would be coming out with a sub-£100 games machine, but a rival to Amstrad’s massively popular PCW8256 - one of 1985’s few UK IT success stories - was also mooted and, by October, was back on the cards, possibly to ship with an emulator to allow it to run PCW software. That was a Syntaxsoft specialism, don’t forget.

Memotech’s principals in 1983: Robert Branton (left) and Geoff Boyd; and Geoff today (far right)

And then, in December, Memotech began advertising the MTX 512 Series 2: a tape-based 256KB model for £99.95, rising to £166 for a version with a clip-on 1MB 3.5-inch floppy and MTX Basic disk extensions. Or, for £264, you could get the MTX plus drive plus 512KB Ram disk plus CP/M plus 80-column card. It was essentially Geoff Boyd selling off the components and MTX computers he’d acquired in order to take control of Memotech.

In January 1988, Your Computer noted: “Memotech is still around, though in a smaller and different form from the original Memotech... still based in Oxfordshire and catering for a loyal but dwindling band of supporters.”

The MTX, then, went out not with a bang but a whimper.

Not so Geoff Boyd, who used the foundation he had created by establishing Memotech 2.0 to build a successful business providing electronics to run stacks of CRTs in video wall configurations. In the late 1990s, the LCD manufacturers moved into the market, using their ability to integrate the control electronics into the displays to undercut existing offerings. Geoff moved on and, still at heart an enthusiast of audio electronics, went on to join UK flat-panel speaker technology company NXT to drive its licensing business. He was there for ten years. Now he runs Coleridge Design Associates in San Jose developing audio technologies.

Robert Branton went on to found Lazy Summer Books, a kids’ publishing endeavour. He has continued to work on software, developing dictionary management code for many of the big names in dictionary publishing. He’s now director of systems a self-publishing site YouCaxton. Thanks, Paraic

Steve Marchant, creator of the SM1 micro, from which the MTX was derived, continues to work with Chris Marvell as Technical Director at Marvell Consultants. After his involvement with Memotech, he also managed the University of Nottingham’s micro labs, and was later Technical Director at image capture company Picsolve. ®

The author would like to thank the many retro-tech fans for archiving home computing adverts, photos and documentation from the 1980s, without whom this feature would not be possible. Thanks to Dave Stevenson in particular. Very special thanks go to Geoff Boyd.

Correction

Arkley actually got in touch on 04/03/19 to say he is a real person who really liked the MTX. "At the time I had a massive interest in the MTX and promoted it in any way I could, with it being such a well built and powerful (real) computer," he said. "I'd no connection with Memotech. I was connected to the home computing trade at the time and much of my intel was from the trade magazines of the time (e.g. the wonderfully and often sarcastic Computer Trade Weekly – CTW).

"It was heartbreaking to see Memotech fail like they did. I still rate their MTX and the few bits of software that made it to the platform. I did have a Spectrum Emulator – which really was a huge admission of defeat. Paying software houses to produce MTX versions of the latest titles would have been money better spent. Then again – that's with the luxury of hindsight.

"With the advent of PCs and games consoles I lost interest in the industry and moved on."