Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/05/24/geeks_guide_gchq/

INSIDE GCHQ: Welcome to Cheltenham's cottage industry

'If this nerve centre didn't exist, neither would I' says Reg man

Posted in Geek's Guide, 24th May 2013 07:05 GMT

Geek's Guide to Britain For staff at the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in Cheltenham, there’s an air of Fight Club about the place. The first rule about GCHQ is you don’t talk about GCHQ.

It’s a well observed tradition, even though there are road signs and a bus route directing you to this highly secret establishment, the nerve centre of Britain's communications surveillance operations.

GCHQ Benhall … does a doughnut keep better secrets? Source: Bing Maps/Digital Globe

The design of the doughnut-shaped building at Benhall has attracted a fair share of attention since its completion in late 2003. Indeed, if you take a look at the site from Google Earth, you might wonder if it inspired Steve Jobs’ plans for a new circular Apple building – a company that also likes to keep secrets.

Benhall is now the primary home of GCHQ and the majority of the service’s 5,300 employees are based here. The organisation’s own website describes itself as “one of the three UK Intelligence Agencies and forms a crucial part of the UK’s National Intelligence and Security machinery”. The other two are the Security Service (MI5) and the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6).

In years gone by, GCHQ in Cheltenham was spread over two sites a few miles apart: Oakley and Benhall. The Oakley site has largely given way to a housing development although some buildings remain with the barbed wire fence rather menacingly separating it from a kids’ play area on the new estate. While undoubtedly unintentional, this incongruousness does appear strangely Soviet – it’s perhaps fitting given Cold War concerns became GCHQ’s raison d’être in the 1950s.

GCHQ Oakley ... recreation and razor wire live side by side these days

I was born into a GCHQ family as my parents met there. As I write, it now occurs to me that if GCHQ didn't exist, neither would I. Spooky. I lived in a GCHQ house, too – purpose built to accommodate the growing workforce – and I could see Benhall's satellite dishes from my bedroom window.

I worked there too, and before I tread further along this telecommunications taboo tightrope I should mention to our colonial cousins that what we have here is the equivalent of America’s National Security Agency (NSA). For me, this association came in handy when applying for a US visa to visit a GCHQ colleague working for that ultra-hush-hush outfit. Mentioning those three initials at the US Embassy had my passport visa stamp in seconds.

Incidentally, I did ask the GCHQ press office if there was any chance of a tour of the building or even some publicity pictures of the interior. Admittedly, there was a bit of wishful thinking behind the former – there were employee family tours when the building was complete – but the answer was no. The polite response to the latter request was that pictures would be considered on condition the article could be viewed before publication. That's against our editorial policy, but chances are they've done that already.

Official Secrets Act warning

and that's just the car park

I decided to take some photos myself, which are no more intrusive than those found on Google Streetview. It was only later that I spotted a "no photographs" sign, but as I was some distance away, I didn’t notice it at first. I doubt I'd notice if I’m now being followed or having my communications tampered with as a result, but it would seem like a waste of time and of public money.

If you do go on a tour of ‘Nam, taking pics aplenty up to the wire wouldn’t be a very good idea. The security staff, many of which are ex-servicemen, take a dim view of this sort of thing.

Choosing Cheltenham

As part of my research for this piece, I dug up Peter Freeman’s 34-page booklet titled How GCHQ came to Cheltenham, which lays out a longer story than I’d anticipated. Freeman details the early years and the decision-making process that saw this sleepy Cotswold town – that for 75 years up to 1945 had a static population of 50,000 – undergo significant changes when GCHQ became operational. The population swelled by 20 per cent in the 1950s with a housing programme in place to support Cheltenham’s new cottage industry: intelligence gathering.

Freeman remarks that the Ministry of Health’s initial views were that “Cheltenham did not want civil servants and already had plenty of local employment”. The Ministry of Works leaned on the Ministry of Health and consequently the town now breeds civil servants.

Early GCHQ history by staffer Peter Freeman

I was reading an exclusive edition of Freeman’s work which features various handwritten corrections and additional detail courtesy of my mother, and she would know being on the 1950s-era Foreign Office recruitment team based above the Ministry of Food bureau in Clarence Street, Cheltenham (rationing was still in operation in post-war Britain). Their task was to find the right stuff to staff Oakley and Benhall.

Yet how GCHQ came to Cheltenham owes more to what the Americans left behind after World War II than any strategic importance to the spa town's location. The Oakley and Benhall sites were purchased by the Ministry of Works in 1939 and building works began for the purpose of housing government departments if an evacuation from London's Whitehall became necessary. During the Blitz, some ministries had to move fast and ended up arriving before work on the temporary office blocks was complete. Each site had six of these utilitarian, single storey, 12-spur buildings that, in total, clocked up over 400,000sq ft of office space.

With the Blitz over, various departments returned to London, and the Americans, now involved in the war, found themselves at these two sites running a major HQ. The US SOS (Services of Supply) dealt with logistics for the European Theatre of Operations, US Army (ETOUSA), and the buildings were used as offices for this communications hub. According to Freeman, the Americans arrived in secret and those coming from London had exclusive trains laid on to keep their movements under wraps. The railway staff at Paddington weren’t so clued up though, and slapped up signs on the platform saying “US Forces To Cheltenham”. As the Yanks dug in at ‘Nam, they consequently installed a substantial network of landlines which remained after the war.

US Forces in covert UK transportation ops … lucky they kept this quiet

Source: HyperWar

The clincher was when Cheltenham was visited by a staffer from GCHQ - then based at Bletchley Park near Milton Keynes - who knew of the site at Benhall, which was where the Ministry of Pensions had taken residence prior to an eventual move to Blackpool. Posing as an Admiralty official on a pensions fact-finding mission, he was granted a tour of the site and wrote up a favourable report of the place. Although there would be numerous inter-departmental and financial wrangles to follow, GCHQ eventually made its home in Cheltenham in the early 1950s.

The great British code warriors

Now established for more than six decades in Cheltenham, GCHQ has origins that go much further back. The Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) was formed in 1919 after World War I, its role being to assess security and coding methods within the government and develop improvements. Well, that’s what the man in the street would be told: its other function was to analyse the communications systems Johnny Foreigner was using. Hence, GCHQ, as it became known in 1946, has since been regarded as a "listening station". It’s not the only one, but it is the most well-known in the UK.

The eternally unassuming Bletchley Park

Originally based in London, the bulk of GC&CS relocated to Bletchley Park in August 1939, later moving to Eastcote in 1946 where there was an established GC&CS site with "analytic machinery" – the term "computer" had yet to catch on. Even though the wartime peak of 10,000 staff had now reduced to a few thousand, Eastcote wasn’t in very good shape, was cramped and couldn’t be expanded. Moreover, keeping it close to London – with the idea of a rapid redeployment farther afield if the threat of war loomed – was no longer practical. The cipher and communications technology now in use didn’t take too kindly to being moved and, with the various preparations involved, could take up to 6 months to reinstal elsewhere.

Eastcote was too close to the capital and a suitable site that could function during times of war and peace became the new strategic focus. When the move finally came, the Eastcote facility transferred to Oakley in 1952. Benhall was earmarked for a consolidation of various radio stations a year earlier, but this was cancelled due to a number of concerns regarding space for the aerials and interference from nearby civil aviation communications sites at Elkstone and Winstone.

Benhall site from 1945: those temporary office blocks hung around for 60 years

Even so, Benhall was established as a technical facility aided by its various workshops. In 1956, the Joint Speech Research Unit (JSRU) was formed in Eastcote but eventually set up home at Benhall in 1978. This lodger unit produced rafts of papers on speech synthesis and analysis. It joined up with the Royal Signals and Radar Establishment in 1986 to become the Speech Research Unit only later to be privatised in 1999. It is now called Aurix, owned by Avaya. Incidentally, the Speech Research Unit should not be confused with the Joint Technical Language Service (JLTS) that, if the ageing sign is anything to go by, is possibly still in residence at Oakley and undertakes a different role, focussing on translation and interpreting services.

Remember those temporary office blocks built in the 1940s? This implicit impermanence became a standing joke on both sites as each decade passed and they were still there. In fact, a few remain at what’s left of Oakley and would be entitled a Civil Service pension now.

I was installed in one of these for a time, which was set up for experiments on magnetic tape, in varying conditions of humidity and temperature. The makeshift lab was nicknamed the "steam room" and I sat there, mostly on my own, creating environments in a chamber with water boiling away to supply the moisture and occasional blasts of CO2 used to control the temperature. I’d monitor the results on a chart recorder and then type in a rather long-winded formula into a Honeywell scientific calculator to make some sense of it all.

You might wonder what on Earth this had to do with the work of a listening station. In short, back then, a lot of tape recorders were used in various remote listening posts, and the idea behind this experiment was to discover what tape formulations worked best in different environments.

Temporary office blocks still exist in what remains of the Oakley site

The block itself was pretty sparse, with aged everlasting linoleum flooring, big cast-iron radiators and draughty single-glazed windows. It would have been nice to have had a radio in there, but bringing in a tranny (that's a transistor radio) from outside wasn’t permitted although sophisticated wireless equipment existed in abundance in other designated areas. Personal tape recorders and cameras weren’t allowed, and you had to call in the official photographer to document any setups you felt deserved a snap. I’d be interested to know how the organisation deals with the abundance of smartphones today. Are they banned or is the place more trusting now, I wonder?

A little bit of Oakley

While Benhall is just a bus journey away these days, if you’re keen to see the last remnants of Oakley, then you can either wend your way through the new housing estate or take a peek over a field from Aggs Hill. The latter is more of a challenge but can be made into an interesting diversion if you’re a fitness fanatic or just fancy an easy way to get to the top of Cleeve Hill by car and admire the view along with the three aerial masts that can be clearly seen from the town.

Hillside retreat: Oakley from Prior's Road

is mostly houses and a Sainbury's car park

If you’ve already done the housing estate Oakley drive-by, then the simplest way to get to Aggs Hill is to travel up Harp Hill where you’ll be on the periphery of Cheltenham’s most exclusive housing stock in Battledown. If you’re a Tour de France enthusiast, cycling up Harp Hill should be a breeze, but the gradient of Aggs Hill is tough. Just keep going to the crossroads sign for Cleeve Common only. When you get to the end of the road you’ll be under three sizeable antenna masts serviced by Arqiva, and you can stroll onto Cleeve Common – dog owners, keep an eye out for sheep.

Cleeve Hill aerial masts: Arqiva site 36223

GPS: 51.921694, -2.010261

The splendour of the Cotswolds notwithstanding, if you did bike it this far, the real reward is whizzing back down Aggs Hill at a frightening rate with a nod to the remaining Oakley site entrance as you corner at the bottom... or hit the Hewletts Reservoir wall. The fun’s not over; there's Harp Hill left to descend – there used to be a hospital at the bottom, but not any more, so take care. If you’re still feeling sporty, or fancy a brew with a view, then The Rising Sun Hotel on Cleeve Hill is worth a visit. Alas, the High Roost Hotel on the same stretch closed in 2003 which was incidentally a US Army hospital during WW2. Oh, and don't forget, Cleeve Hill has a golf course too, which, for a fee, anyone can get their balls out and whack them off among the sheep.

Down the tubes

When I worked at Benhall, which in the heyday of the two Cheltenham sites was focused on R&D – the job titles tended to be variants of scientific officer, technician (radio repairman) and radio operator. Being there also meant I spent most of my time in the new-ish 1970s building. The eternally dodgy lifts had bright puce panelling that was so intense you couldn’t wait to get out, and some days you’d hear bagpipes playing in the quadrangle at lunchtime. This was no state occasion, just some chap engaged in windbag practice – optional for civil servants.

GCHQ Benhall 1970s style: canteen (foreground left), archway for stores (background right)

The labs themselves were spacious and well-equipped. Being a junior grade, I learned how to use sophisticated test equipment there but didn’t see the attraction of playing Star Trek on the lab’s DEC PDP-11 during breaks. It seemed like a lot of typing was going on but not much else. I’d be more inclined to have a go at building a guitar effects pedal instead; “working on a foreigner” being the phrase used to describe any pet projects or domestic repairs undertaken on site.

Benhall had its own immense stores and on your first day in this high-tech community you’d go through the various catalogues – some on microfiche – to find the equipment you’d need to build up your toolkit. It felt like being in a sweetshop but you’d need a senior officer’s signature to get it all and some gear would be serialised too, so it wouldn’t go astray, even the bloody leather tool bag. Going to stores was often welcome respite from the hum of the lab as nobody ever turned off equipment and even the oscilloscopes would add to the fan noise.

Typically, the lab would have its own reserve of resistors, capacitors and various silicon chips, which would be routinely checked. You could even put in an order to the stores using the Lamson tubes that featured on every floor. We’re talking of the days before email here, and so messages were sent in small capsules along a pipe using compressed air. I remember seeing these in department stores when I was still in short trousers and was amazed to find this technology hailing from Victorian era in such a sanctuary of tech.

What made matters worse was that some bright spark had decided to deploy a rectangular Lamson tube array. The thinking was that this would allow for larger payloads so you could get stores to send you back those resistors and capacitors using a Lamson tube. It would have been great if it wasn’t for the fact the capsules were forever getting stuck. Circular objects in a round pipe: good. Rectangular objects in a flat sided duct: bad.

At about 10.15am and 3pm the official 15-minute tea break would be stirring into life. Some labs would have a proper sit-down in the corner while just a table and kettle would suffice for others. I remember once forgoing the usual chatter of current affairs and returning to my workbench with a cuppa during a break. The lab was now empty apart from me and then the Principal Scientific Officer (PSO) wandered in – the department’s head honcho. He asked me where everyone was. I replied that they were having a "mass debate" in the tea room. He gave me a look of utter disgust and wandered off. It took a while for me to realise that I should have chosen my words more carefully, as even a communications expert misunderstood my mention of mass debating.

Surprising perhaps given the environment was equipped with Wayne Kerr knobs and tools aplenty.

Actually, the issue of misinterpretation reminds me of a situation my Dad described to me regarding context in intelligence gathering, which I’ll come to in a moment. The late Steve Dormon spent a lifetime at Oakley; by comparison, I spent a lunchtime at Benhall. Oakley had different clerical and executive officer grades – fairly nondescript titles that veiled the true nature of the top-secret analysis many were involved in. While Benhall was all about hardware and technology, Oakley had admin and training at the front of the site, with beautiful minds working on intelligence analysis far from the madding crowd.

Doughnut, anyone?

Inside, there are cafés, bars plus a restaurant and a gym. An internal street is the hub of the site, joining up these facilities and the various departments. Being circular, you're no more than five minutes walk away from anyone in the building. In the basement you can get around quicker, as an electric goods train runs down there delivering stuff. An underground road handles more sensitive materials.

Other startling specs include the computer area that is said to be the size of the Royal Albert Hall. The doughnut frame used 250,000t of concrete, the electrical wiring covers 6,000 miles and BT laid 5,000 miles of cable and 1,850 miles of fibre. And to cap it all, the estimated total cost hit £1.2bn. Yet truth be told, the site is actually more interesting to view from aerial shots than from ground level, as it’s bit like a frisbee on a lawn: there’s not a lot to see unless you’re on top of it.

Built for £337m using cash from the controversial Private Finance Initiative (PFI), it was the biggest project of its kind

With this in mind, I took a night-time trip up to the top of Leckhampton Hill hoping a telephoto shot of the site would reveal some twinkling Stargate SG-1 charm. Apart from being farther away than I’d thought, it turns out to be quite difficult to see at night. A cluster of street lights hints at its whereabouts, but the building itself seems to be dressed in stealth bomber clothing, as it’s virtually invisible. Cool.

Grounded: Avro Vulcan B2 XM569 cockpit

A daytime pilgrimage is easy enough, as there are signposts everywhere. Finding the place is one thing, entering it is another – it’s definitely members-only, having travelled the length of Hubble Road only to gaze upon the high-security car park. So, what next? Well, you could always go for a spot of flying at Gloucestershire Airport, Staverton on Bamfurlong Lane.

The airport used to be home to the beloved Skyfame Museum, but it has since expanded and become more of an aviation industry village. However, there is the revamped Jet Age Museum that has relocated to the north of the airfield – part of the Meteor Industrial Estate – and should be open to visitors later this summer. It’s a shrine to early jet propulsion as the area is linked with the development of the Gloster Meteor – the first production jet aircraft based on Sir Frank Whittle’s engine design.

Sky drive: Gloucestershire Airport, Staverton

If that sounds all too exciting for you, The Aviator café and restaurant at the airport has a full menu of grub to suit kids, veggies and carnivores alike. More importantly, the bar serves Wadworth's 6X which might settle your nerves to consider taking flying lessons at the Flying Shack just down the road. You can’t miss it as there’s an Avro Vulcan B2 XM569 cockpit in the car park. Oh, and keep an eye out for the type FW3/26 WW2 pillbox on the roadside overlooking the airfield. But if terra firma and tinkering with cars is more your style, perhaps a trip to nearby Harry Buckland's scrapyard would suit? It's a local institution, having been going since 1935, so you never know what you might find there.

Tinker, tailor...

Oakley had its own bar too, and no doubt the thinking behind this was to keep lubricated chatter within the secure confines of the grounds. The fact that the place sold godawful keg bitter – I think it was Whitbread Tankard or Ind Coope Double Diamond – meant that most self-respecting drinkers ended up at The Bayshill Inn. Not exactly local to Oakley but known for a decent pint of Wadworth’s 6X. There was even a mural of regulars painted in there which included an ale fancier from GCHQ. No, you don't have to wear a burqa or similar to work there.

At one point I found myself at The Bayshill Oakley on a training course. During the lunch break I asked a security chap if I could go up the hill to visit my Dad. “Oh no son,” he scoffed, “you’ve not got clearance to go up there.” Needless to say, bring-your-kids-to-work week has always a bit of a damp squib for a lot of families in ’Nam.

Bond calls for help to decipher the mumblings of his tailor

Source: Anthony Sinclair

Indeed, “how was your day?” tends to be a conversation killer for GCHQ employees too, but I do recall my Dad telling me about a course he attended that sounded a lot more fun than anything I’d been on. The gist of it was to do with context and how information could appear abstract when it lacked any reference points. The way this was demonstrated on the course was to play a muffled recording that sounded like people talking in the adjacent room. The group was asked if they could tell what was being discussed and none could. Then they were told that it was a conversation between a man and his tailor. The recording was played again and, armed with this reference, they could all understand it. I never found out if the mention of whether sir dresses to the left or to the right implied any political leanings.

Just for the record, it’s worth mentioning that the good folk of GCHQ are not of a hive mind and don’t all share the same political views. So don’t think for a minute that snoopers’ charters proposed by the government of the day are universally supported. While the technology may exist to follow a political whim, I’m sure most GCHQ bods would rather be tracking greater dangers than getting bored to death trawling through domestic emails or following misguided tweets.

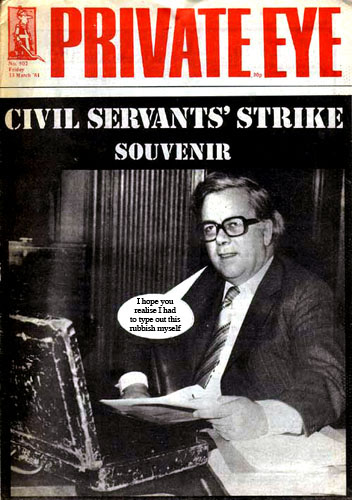

Source: Dink Cartoons

Talking of politics, Thatcher initially proposed banning unions at GCHQ following the Civil Service strike in 1981, which some GCHQ personnel observed. I remember a handful of pickets at the site entrance, but it was all pretty passive. Still, Mrs T’s thinking behind the ban was that this security service could not be compromised by strike action. There was quite a fuss, to put it mildly.

Badge of honour?

Source: UnionNews

Somewhat naïvely, I was surprised by this as I had tried to join the union myself way before the ban arose. Despite phoning up the local union rep, I didn’t get the followup information I was expecting. The combination of my low wage (I wasn’t exactly looking forward to paying the dues) and the mutual apathy that ensued meant I didn’t become part of the union and was left with the distinct impression that there was no obvious urgency for members.

It’s a pity this didn’t work out though, as Thatcher bribed compensated each GCHQ union member with a £1,000 cash payout for abandoning their respective trade union. The ban finally took effect in 1984 and 14 workers were sacked for refusing to relinquish union membership. It took until 1997 for unions to be permitted once more at the establishment.

Reproduced by kind permission of PRIVATE EYE magazine

Click for a larger image

I was there when the Falklands War broke out and although the conflict was fairly short-lived, the mood definitely changed during this period. Nobody was being jingoistic, and a single-minded seriousness prevailed. If anything, there was a sense of disappointment that we found ourselves in this situation, as part of the purpose of the organisation was to be so well-informed as a nation that conflicts could be avoided. Remember, GCHQ was there to monitor signals from around the world, as well as what was happening in Blighty.

Another pearl of wisdom from my Dad on this matter was that the Americans had warned us that the Argentines were gearing up for battle way ahead of their invasion of the Falkland Islands back in 1982 and that for some reason, the powers that be here in Britain had ignored this intelligence from our colonial cousins. I’ve no cause to doubt what I was told back then. History is littered with similar situations of intelligence being deliberately ignored or even sexed-up for political reasons.

Anyone who has taken an interest in the tales of secrecy at Bletchley Park during wartime will be aware that there is a "need to know" mindset, where people worked in separate teams without meeting or discussing their tasks with others. When I first heard this phrase at GCHQ I mistakenly thought it meant that one needs to know – like we were sharing stuff in some motivational way.

Of course, the emphasis is actually, do you need to know? Oh well, I was not long out of school so such subtleties were initially lost on me. If people were coming and going in secret, it naturally wasn’t obvious at all. I do recall the "cell" though, which I noticed one or two people emerging from occasionally. It was some kind of high-security broom cupboard, although it could have been like a Tardis inside, but I never found out. I guess I didn’t need to know. Still, it’s no surprise that places like that existed, whether for storing sensitive documents or working in a shielded environment. Maybe there was a Lamson tube in there going all the way to Cheltenham race course bookmakers.

The BBC managed to get a tour of Oakley before the demolition began and produced a couple of videos that include the high-security vaults, massive code-crunching computing areas and a backup power generator that could run the whole town.

Untold stories

While the mindset of secrecy is encouraged with good reason, it does have its drawbacks for those with ambition. I recall a few jaded souls who had stayed so long that, despite having exceptional talent, would find it difficult to leave because they couldn’t tell a future employer on the outside what they’d been up to. So unless they could find a government job posting elsewhere, they were destined to remain residents of Hotel Gloucestershire: you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.

On the other hand, high-flyers fresh from university would find they had an opportunity to shine given the brain-tingling tasks they had to tackle and the resources at their disposal. Don’t be shy of working there if you have the skills, but you might want to keep an eye on the calendar unless you’re planning on being a lifer.

That being so, the secretive side of things can begin to seep into your thinking. Who’s watching you? Surely, somebody must be from time to time as a routine security measure so you don’t end up becoming vulnerable financially or in other ways.

“My, that codecracker Jenkin’s is a lucky chap, he’s nearing retirement and that gorgeous 19-year-old Chinese girl he met at the bus stop has totally fallen for him. Who’d have thought it?”

Just how closely you are monitored can tease the imagination. On this point, my Dad would joke about voting Communist to see just how secret the secret ballot was. I don’t suppose he ever put it to the test, but if you work there and feel lucky when the next election comes around, why not give it a shot?

Working there affected my thinking too, as it’s only in recent years that I’ve stopped dreaming about returning to the place to embrace the technological challenges and achieve great things. Yes, I would finally have a crack at Star Trek and get to the Emeritus level, if only I could find a PDP-11 handy. Still, I picked up useful transferable skills there, as fault tracing combined with being a dab hand with soldering iron worked out very well when I found myself in London working in recording studios.

Naturally enough, the establishment has moved with the times. The intense efforts to monitor Cold War threats have largely given way to focus on the terrorism and cyber-security issues of today, as highlighted on the GCHQ website. Whatever you think about the secrecy of the place, the intelligence services endeavour to keep us safe. It was a motivating force for those who’d experienced WW2 and went on to take jobs at GCHQ so this country wouldn't experience anything like that again.

I've no doubt it's a commitment that continues to this day: so far, so good. ®

GPS

51.898835, -2.120497

Post code

GL51 0EX

Getting there

A40 Cheltenham