Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/03/15/maarten_schmidt_quasar_anniversary/

Schmidt still scanning the skies 50 years after defining the quasar

El Reg talks with legendary astronomer about gamma rays, GPS, and Hitler

Posted in Science, 15th March 2013 22:37 GMT

Interview Fifty years ago this Friday Dutch astronomer Maarten Schmidt revolutionized his field with a paper on quasars, the energy sources that now act as terrestrial guide points in our exploration of the cosmos.

His initial 1963 paper was disputed by some of the biggest names in astronomy, got him on the cover of Time magazine (joining such august figures as Edwin Hubble), and overturned much of conventional thinking on the steady-state universe in favor of the Big Bang theory of an expanding reality.

On the anniversary of his discovery, Schmidt talked with The Register on his inspirations, discoveries, and plans for the future.

Radio Number One

Look up into the night sky and you won't see a quasar, but gaze through a radio telescope and they burn with brightness. Their name – quasi-stellar radio source – defines them, and they pour out such huge amounts of electromagnetic energy that they were first thought to be some of our closest galactic neighbors.

It was the invention of radio telescopes that really began to open up our understanding of quite how complex the universe is. Seeing stars is one thing, but detecting the emissions of interstellar objects on non-visual wavelengths is another, but it has led to a much deeper understanding of time and the structure of both our own galaxy and its place within the universe.

Still going strong at 84

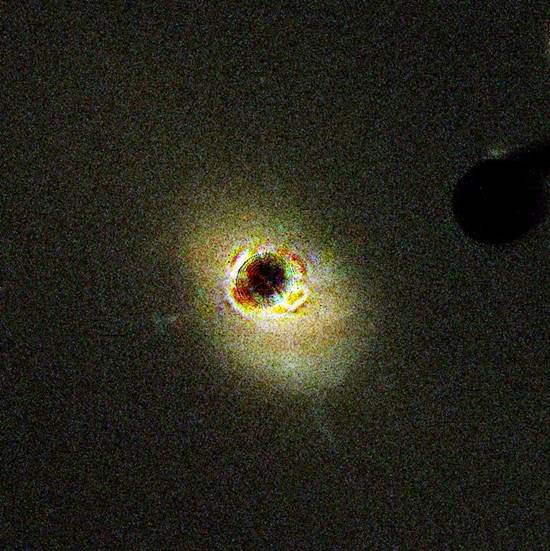

Schmidt's insight was to measure the redshift of an energy source known as 3C 273 and to realize that, far from being a close star, it in fact shone from three billion years back in our universe's history. He theorized in a 1963 paper in Nature that the object was a mass about one light-year across and was driven by a super-massive black hole at a galaxy's core.

"I realized immediately the importance of the discovery because it allowed us to probe deeply into the universe and back in time with objects that are bright, and therefore I saw we would be able to use quasars to go to very large redshifts," he told us.

His theory has finally reached acceptance (against some stiff competition), and at the ripe old age of 84 Schmidt is still examining the universe, albeit from a slightly different standpoint.

Hitler's contribution to astronomy

Schmidt was a 10-year-old living in the northern Dutch town of Groningen when the German army invaded his country. Encouraged by an uncle, he used the blackout conditions imposed for the next five years to view the stars without the light pollution that curses earth-bound optical telescopes.

"First I had a chemistry lab at home and then, of course, the usual small explosions," Schmidt reminisced. "And somehow the universe and the stars attracted me, and it started in a very basic manner but developed and became my career."

Quasar 3C 273, the first identified quasar

He received encouragement in his career from his family (although his grandmother warned him that he'd ruin his eyesight) and after the war had ended he was able to resume his studies and apply to study astronomy.

Schmidt studied at the University of Leiden under the now-legendary Professor Jan Oort, who had "borrowed" a German radio aerial during the war to jury-rig a radio telescope, and was investigating his now-confirmed theory that comets came from a band of matter outside the Solar System now known as the Oort Cloud.

In 1956 Schmidt earned his PhD, finishing with a white-tie oral examination in which he answered questions on not only cosmology but also topics such as homing pigeons and the need to establish right of way at traffic roundabouts – examiners were a lot tougher back then. Oort recommended Schmidt for a Carnegie Fellowship and he took a boat to New York to check out the New World's telescopes.

He spent a happy two years using the 60- and 100-inch telescopes at the Mount Wilson Observatory near Los Angeles, and was offered a position at the California Institute of Technology. However, he could not accept, he said. "I felt loyal to Leiden so decided to return. But in November, when I returned to Holland, it was foggy and wet for a solid month and it was very dispiriting."

A year later, CalTech renewed its offer of a professorship and Schmidt made the decision to leave the land of his birth and head to pastures new. He emigrated with his wife and two children in 1959 (Dutch bureaucracy being what it was, the paperwork took a year to sort out), joined the university that year, and remains there to this day.

A shift in time

Schmidt spent long nights at Southern California's Palomar Observatory zipped into an electrically-heated flight suit against the killing cold, studying radio emissions in space. He soon grew intrigued by the huge sources of energy he saw there.

NASA's estimation of what a quasar could look like

Fellow astronomer Tom Matthews had begun to measure the redshift of these radio sources, and was getting results that suggested that they weren't as close as had been thought, but instead light-years further away. But the problem was that under to the prevailing view of the universe as being in a steady state, expanding constantly but with an even mix of matter inside, this wasn't possible.

Quasars exist only far back in cosmological time and aren't evenly distributed, as they would have been under the steady state theory of the universe that was then championed by such prominent figures as Sir Fred Hoyle. Quasars are a much better fit in the Big Bang theory of the universe, where certain types of objects form at specific times in the universe's growth cycle.

"Some prominent astronomers formed the opposition and would not believe what was going on," he explained. "But I liked Fred very much, we were certainly good friends. He was fantastically original and intelligent and extraordinarily creative."

Guiding lights

All this might sound very esoteric but there are plenty of practical applications to Schmidt's quasar discovery – not least the possibility of GPS here on Earth.

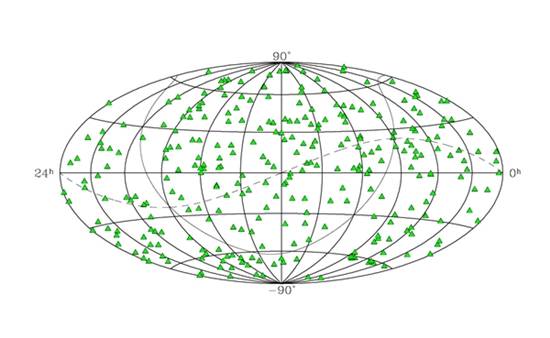

Because quasars are so far away, they are incredibly stable in their positioning, and as some of the brightest objects in the sky they are easily recognizable. In 1995, NASA completed its first International Celestial Reference Frame (ICRF) map of 600 quasars, now has over 3,000 logged in, and the map is the fundamental reference system for astronomy positioning.

The precise mapping of quasars has applications on Earth and beyond

The position of these quasars is used to guide GPS satellites as they encircle the Earth from precise points to coordinate data. Thanks to the work of Schmidt, quasars are their guide-points, and their emissions could conceivably be used as navigational markers for space travel as well.

Quasars are, however, a dying breed. They appear to be a feature of the early life of the universe when there was plenty of fuel for the black holes thought to drive them. After 30 years of study, Schmidt is devoting the latter part of his career to the study of gamma ray bursts, mysterious bursts of energy from back at the beginnings of the universe.

Gamma ray bursts were first detected in the 1960s by US military Vela satellites, which were lofted to keep an eye on the Russians and make sure they weren't breaking the nuclear weapons test ban. They detected the gamma radiation from a distant point in the universe, and it's now thought that these bursts are generated by supernovae or the merging of stars.

At 84 Schmidt is still going strong, although he said that he appreciates the use of CCDs in the field, since it means no more long nights sitting in damp fields or on frigid mountain-tops. Eventually he says he'll be forced to retire from Caltech, but that won't stop his sky-gazing.

"Astronomers are among those who you never know when they are retired or not because we keep at it," he said. "All astronomers love the work they are doing – they are dedicated, and perhaps even obsessed." ®