Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/03/01/aerial_surveillance/

Spies in the sky: The leaps and bounds from balloons to spook sats

A brief history of aerial surveillance around the globe

Posted in Science, 1st March 2013 08:34 GMT

Picture special In just 230 years, humanity has progressed from its first faltering flights to the capability to photograph from space an object the size of a grapefruit - a testament both to technological progress and our need to keep a close eye on the world around us.

The advancement of aerial surveillance and imaging has been driven in large part by the military, although it was a civilian who first returned photographs from aloft.

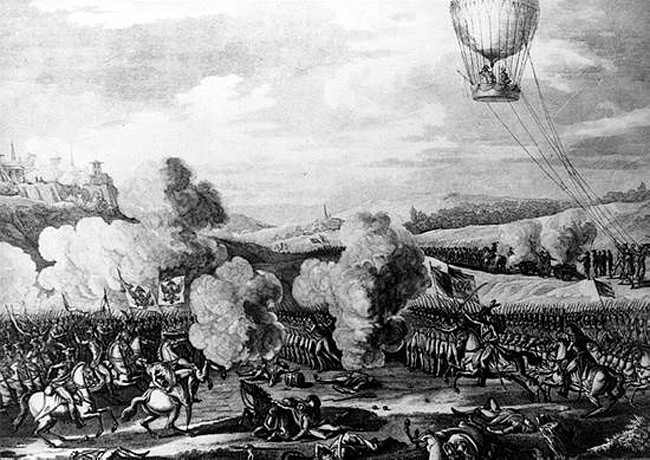

In 1783, a hot air balloon constructed by the Montgolfier brothers provided the vehicle for the maiden manned ascent, and in 1794 the French army realised the potential of airborne observation at the Battle of Fleurus, where the balloon L'Entreprenant contributed significantly to its victory over the Coalition Army.

The British and American militaries began to explore the use of balloons in the second half of the 19th century, with Union forces in the American Civil War opting for hydrogen to lift artillery-spotting platforms.

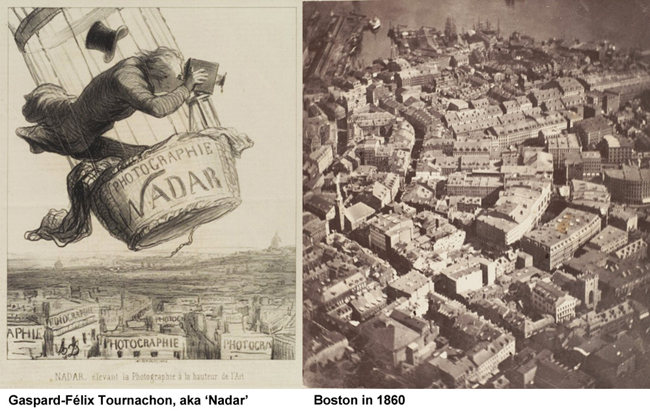

It was back in France in 1858, though, that Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, aka "Nadar", captured aerial photographs of Paris from a balloon, marking the birth of aerial photography. These images do not survive, and an 1860 view of Boston recorded by James Wallace Black and Samuel Archer King has the honour of being the first existing example of the world snapped from on high.

By the outbreak of WW1, balloons continued to serve as platforms for aerial observation, albeit vulnerable ones with their hydrogen-filled bulks floating above the battlefield offering tempting targets.

As the war progressed, and photographic equipment evolved rapidly in response to the need for intelligence, dedicated reconnaissance aircraft were fitted with cameras able to return detailed images of the destruction below, such as the fate of the Belgian village of Passendale, erased from the map during the Third Battle of Ypres:

The aircraft which captured the carnage proved as vulnerable as hydrogen balloons to fighter attack, and by WW2 a viable aerial reconnaissance vehicle would need altitude, and above all speed, to have a decent chance of survival.

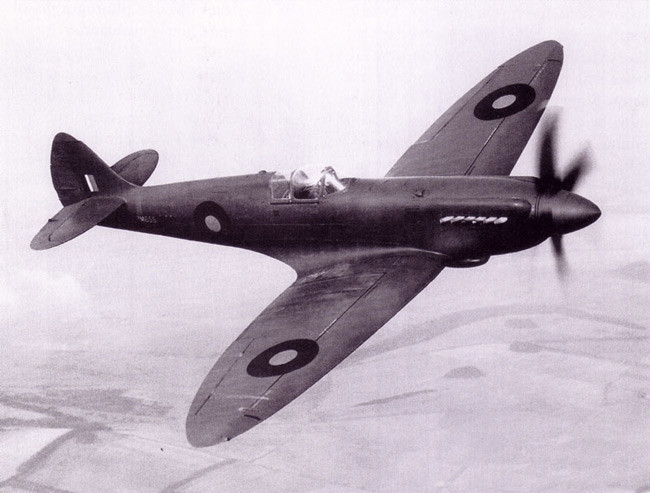

Aircraft such as the Spitfire PR XIX and Mosquito reconnaissance variants, stripped of their armament and armour, proved highly effective in dodging enemy fighters and delivering vital intelligence.

Whereas as a WW1 German Albatros C.III reconnaissance biplane trundled along at 140km/h to a maximum height of 3,350m, the PR XIX soared to 12,200m at 595km/h.

The RAF's PR planes - and their US counterparts including the F-6 Mustang and Lockheed F-5 Lightning - proved an indispensable weapon in the war against Hitler. In June 1943, the British famously spotting the V2 testing site in Peenemunde, revealing the fledgling technology which would later lift man, and spy satellites, into orbit:

The Soviet menace....

As the dust settled on WW2, the West turned its attention to the Soviet threat. The US obsession with what exactly was going on behind Iron Curtain prompted it to sink huge resources into three lines of surveillance attack.

The first was an evolution of the balloon platform, which used the US Navy's enormous "Skyhook" meteorological globes (pictured) as a basis for dispatching camera gondolas over the Soviet Union.

The first was an evolution of the balloon platform, which used the US Navy's enormous "Skyhook" meteorological globes (pictured) as a basis for dispatching camera gondolas over the Soviet Union.

In 1956, the resulting "WS-119L" system was ready to fly into enemy airspace, under the codename "Genetrix". The balloon was designed to float at around 16,800m for airborne payload recovery by a converted C-119F cargo aircraft.

For the effort and expense required, the results from Genetrix were modest. Almost 450 balloons were launched, of which around 380 actually reached their target airspace, where 300 were either shot down or came down prematurely due to malfunction.

Simultaneously, work was progressing on the U-2, whose high altitude capability was intended to keep it out of range of Soviet fighters and surface-to-air missiles.

While the WW2 reconnaissance Spitfires and Mosquitos relied largely on speed for safety, the U-2's modest 690km/h cruise speed wasn't though to be an issue at its 70,000 feet operating altitude.

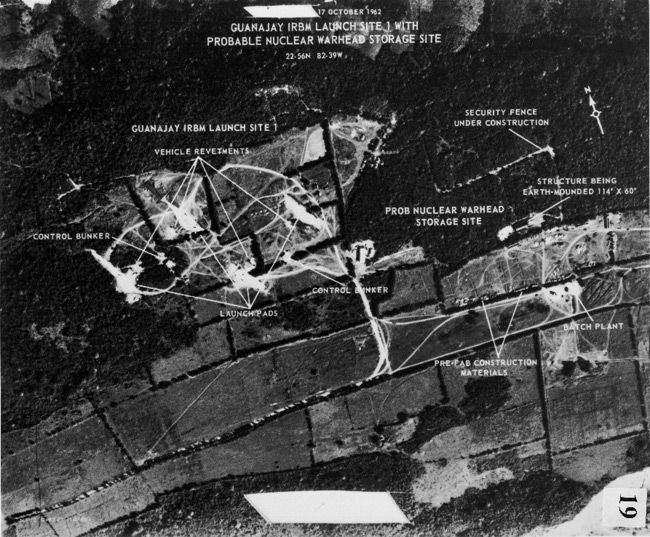

The first U-2 overflight of the Soviet Union was in July 1956. Notable successes during the aircraft's career included the revelation of Baikonur Cosmodrome to US eyes, and identification of Russian missile sites during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962.

However, the belief that altitude alone meant immunity from enemy intervention proved erroneous, as pilot Gary Powers found out when he was downed over Sverdlovsk in May 1960 by an S-75 Dvina surface-to-air missile.

The capture of Powers and the remains of his aircraft proved a huge embarrassment to the US. In October 1962, Major Rudolf Anderson was killed when his U-2 was downed over Cuba, again by an S-75 Dvina. To address the U-2's shortcomings, work began on the SR-71.

The SR-71's 25,900m ceiling was impressive, but its Mach 3.3 (approx 3,530 km/h) top speed allowed it to simply outrun the opposition, including missiles.

It first flew in December 1964, completing over 3,500 mission sorties (all variants) until its swansong flight in 1999. Of the 32 examples built, 12 were lost to accidents, and none to enemy action.

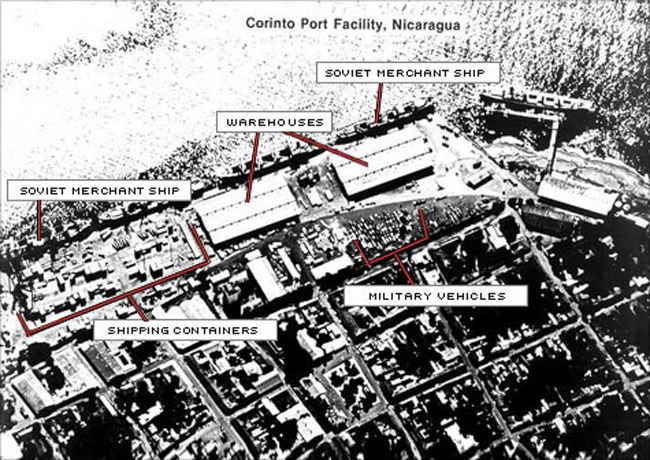

Like the U-2 over Cuba, the aircraft proved a useful tool in providing evidence of Soviet activity in America's back yard. In 1982, the US released an SR-71 photo of enemy merchant ships in Corinto, Nicaragua, as part of its campaign to demonstrate the USSR's backing of the Sandanista government:

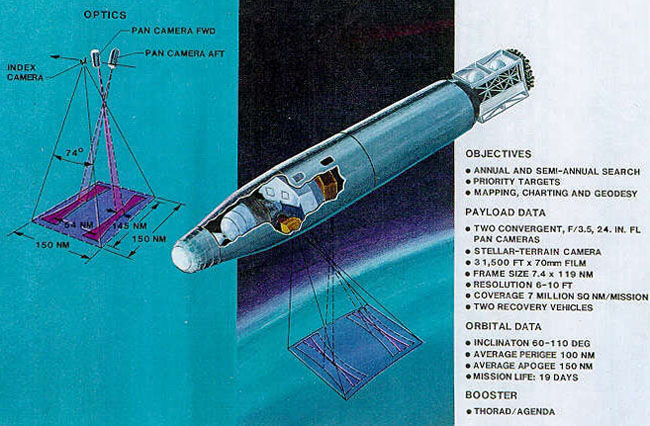

Before the SR-71 took to the skies, and as the U-2 plied its trade over hostile lands, the US was attempting to get off the ground with its most ambitious aerial reconnaissance programme - a satellite system codenamed "Corona".

Spurred by the Soviet's early lead in space with the launch of Sputnik in 1957, the ultra-secret Corona proposed the use of a Thor ballistic missile first stage and "Agena" second stage to lift a photographic payload into Earth orbit.

The project gained extra urgency following Gary Powers' capture by the Soviets in 1960, which prompted the US to cease U-2 missions over the USSR. After 13 failed mission attempts in 1959-60 - mostly revolving around launch vehicle malfunction - a Corona launch in August 1960 finally returned footage covering 2,655,000 square kilometres of territory.

To retrieve the precious film, Corona used the same airborne recovery system developed for Genetrix. The US Air Force's "Samos" satellite programme (1960-72), experimented with cameras which could scan and transmit images to Earth via radio, apparently to poor effect.

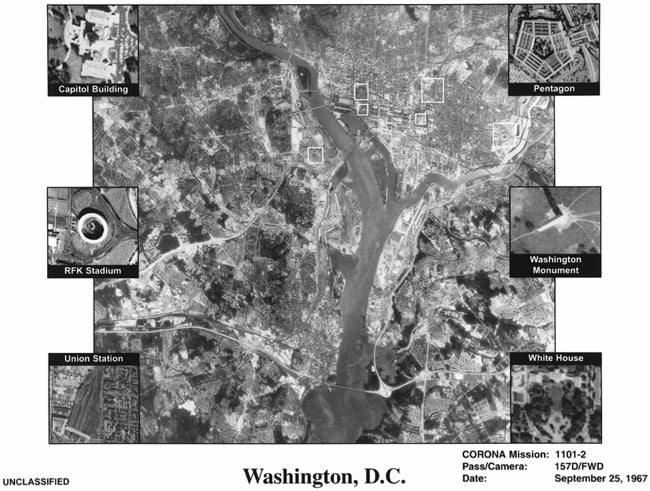

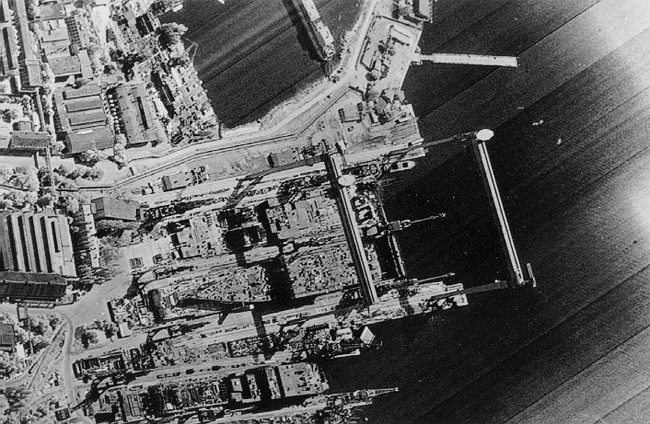

The considerable effort required to obtain Corona images paid off with results that were of sufficiently high definition to pinpoint key installations:

US satellites continued to use recoverable film stock until until the development of the KH-11 series of satellites in the 1970s. These were the first to boast electro-optical digital imaging and, accordingly, provide real-time footage of their targets.

In 1984, a former worker at the US's Naval Intelligence Support Center leaked several KH-11 images of the Nikolaiev 444 shipyard in the Black Sea to Jane's Defence Weekly. One, showing construction of a Kiev-class aircraft carrier, demonstrated the impressive capabilities of US spy satellites:

Satellite imaging continues to advance, both in the military and civilian arenas. As commercial companies offer high-resolution snaps to the public and services such as Google Earth, the spooks are still busy with classified ops, such as last year's NROL-36 launch.

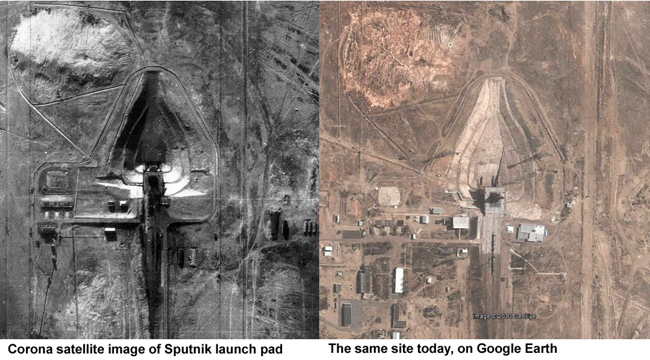

As an example of just how far the technology's come, compare a Corona image of the Sputnik launch pad at Baikonur Cosmodrome, obtained at vast effort and expense on good old-fashioned film back in the 1960s, and the same site today, available free at the click of a mouse to anyone with an internet connection:

We can thank the CCD for the today's high-resolution satellite imagery, but until the 1970s, everything shot from above had to be recorded on physical media.

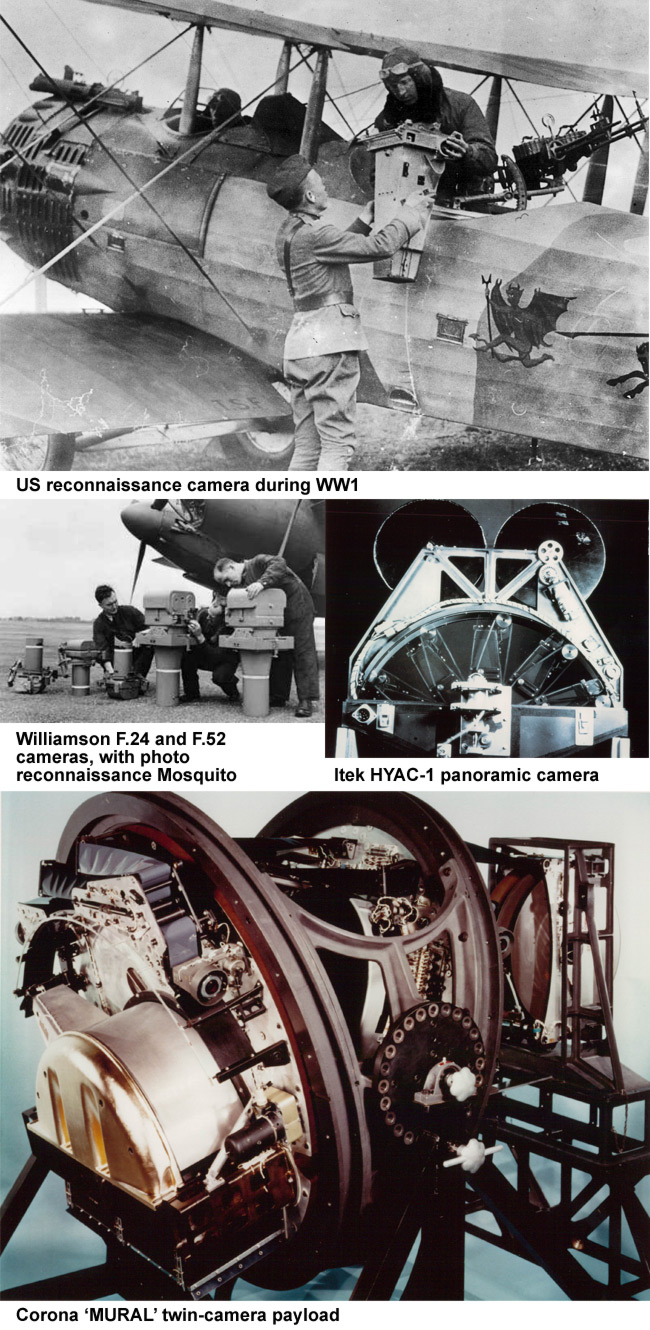

No doubt Gaspard-Félix Tournachon struggled aloft with a glass plate camera for his first shots of Paris over 150 years ago, and by the Great War aerial photographers were still grappling with cumbersome devices, albeit a little more user-friendly.

By 1917, the British Williamson P7 camera packed a handy magazine of 24 glass plates of 5in x 4in, but the same manufacturer's WW2 F.24 had embraced roll film, offering up to 250 5in x 4in exposures.

The F.24 system offered interchangeable lenses at focal lengths of 5in, 8in, 14in and 20in, but the image format lacked detail at even the longest of these when photos were taken from high altitude.

The larger F.52 used a 8.5in x 7in film format, with up to 500 exposures available in a single magazine. Optional longer lenses of 36in and 40in focal lengths addressed the resolution from altitude issue.

Post-war surveillance programmes saw the design of increasingly complex roll-film cameras, with many of the US's needs met by the Itek Corporation. The company's HYAC-1 panoramic model, used in the Genetrix balloon missions, led to 70mm film stock models for Corona.

The first Corona launches used a single camera, quickly replaced with a twin-camera set-up dubbed "MURAL" (see above). The cameras' 24in (610mm) focal length lenses - ultimately supplied by 4,900m of film each - could initially resolve objects on the ground of 12m in diameter.

Improvements in the system allowed later Corona satellites to resolve objects just 1.5m in diameter.

By contrast, the folding optics telescope design of the KH-11 satellites' cameras, with a primary mirror of around 230cm and an 800 x 800px CCD, could - based on analysis of leaked photographs - resolve down to 14cm.

While the prospect of photographing a grapefruit from space is a delicious idea, high-altitude fruit surveillance is sadly beyond the pockets of mere mortals.

Next week, we'll have a look at the thriving DIY spy-in-the-sky scene - from UAVs to High Altitude Ballooning (HAB), and give a few pointers as to how those with less than multi-billion dollar budgets can mount their own aerial reconnaissance mission.

In the meantime, we'll leave you with this montage from our Paper Aircraft Released Into Space (PARIS) mission, demonstrating how a balloon, a tank of helium and a $100 camera can provide breathtaking bangs for not many bucks...

®