Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/02/16/space_asteroid_impact_inevitable/

The universe speaks: 'It's time to get off your rock!'

Long-term civilization on a single planet is impossible

Posted in Science, 16th February 2013 02:29 GMT

Comment The twin visitations from our solar system on Friday – one expected and one not – are yet another signal that mankind really needs to get out and about a bit more if we are to survive as a long-term species.

Those with an interest in space had already blocked out Friday on our calendars for the flyby of the asteroid 2012 DA14 a scant 17,150 miles (27,600 kilometers) away. But over a thousand Russians are nursing their wounds from an unexpected airbursting meteor, parts of which now appears to have just missed a major nuclear facility.

Russia has had more recorded impacts from space junk than most, thanks to its vast expanse and extended latitude over a good chunk of the Northern Hemisphere. The 1908 Tunguska Event is the most famous; that explosion went off with the force of a thermonuclear weapon and left massive devastation. By some estimates if it had come minutes earlier the major cities of Europe could have been in the firing line, including London – then the world's capital city.

As for 2012 DA14, it gets its prefix because it was discovered barreling down on Earth less than a year ago – and today's flyby was very close indeed. In astronomic terms 17,150 miles is nothing, and if its trajectory were slightly altered we'd have been looking at a major impact, although on the bright side global warming wouldn't have been such a major issue any more.

This isn't going to descend into mystical predictions of a deity or Mother Nature–type universal spirit sending us a message; science doesn't work like that. Friday's visitations are nothing more than a reflection that we now know what asteroids are, can detect them at ever greater distances, and are starting to look actively for them – but still get clobbered unexpectedly.

As our understanding of the Earth and its place in the cosmos grows, it has become increasingly clear that if humanity is to survive to a decent age in galactic terms, then we're going to have to have a backup plan because we could be bombed back to the Stone Age (or fossilized altogether) at any time.

Warnings from history

Mankind's history is replete with tales of glowing balls in the sky and falling rocks as a signal of doom or massive upheaval.

The Bayeux Tapestry shows Halley's Comet presaging doom for Britain as the French William the Bastard set off for England to change his suffix to Conqueror back in 1066. Further back in the fourth century, the Roman emperor Constantine is thought to have been inspired by a meteor to beat his rival Maxentius in a battle that unified the empire.

Looks like it's going to be one in the eye for King Harold

Religions have always been quick to try and explain such things. Contemporary historian Bishop Eusebius wrote that Constantine believed the meteor was a sign from the Christian god, and this led the emperor to convert and establish the faith's major status. The Black Rock that devout Muslims make pilgrimages to is also thought to contain a meteor, and even today there are many who will claim that the latest Russian explosion is a sign from some god or other.

But before we get too snooty about faith, let's not forget that it has only been in the last 250 years or so that in some quarters of science have even accepted the existence of falling chunks of rock from the sky. In 1803 the French Academy of Sciences was hotly debating the issue when a shower of 3,000 objects fell on the nearby town of L'Aigle in broad daylight, which settled the argument once and for all.

Since then explorers and geologists have found a few giant impact sites, particularly in large meteor crater lakes around the world, but it wasn't until we moved into space and started looking down on the planet's surface that we saw that there were many more massive impacts than first thought.

One of the most worrying for humanity if the now infamous Chicxulub impact, caused by a six miles (10 km)–wide monster rock that effectively wiped out the prime species of the day, leaving mammals to pick up the pieces. It has recently been suggested that our search for intelligent life should be confined to planets and systems that suffer minimal bombardment for just this reason, since too many impacts may leave it impossible for advanced species to develop.

A meteor could even have accidentally brought about the end of modern civilization back in 1972, when one got within 35 miles of ground-level over Utah. Had it hit, projections suggest a two kiloton airburst directly over the US that, given the state of Cold War tensions at the time, might have triggered global thermonuclear war, dipping us into a medieval lifestyle for generations.

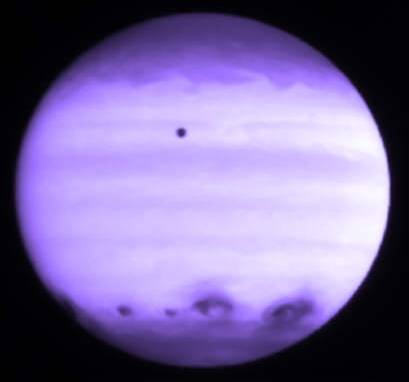

The scars of Shoemaker Levy

Then in 1994 astronomers got a birds-eye view of the kind of asteroid strike that might kill all life on Earth right down to bacterial level. Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 broke apart and slammed into Jupiter at 134,000 miles per hour, with just one fragment punching a 7,450 mile (12,000 kilometer) hole in the gaseous giant that took months to heal over.

Fiddling while Rome burns

Earth's astronomers were lucky with Shoemaker-Levy, since they knew it was coming and the planet was in an excellent position to observe the impacts. The resulting damage caused a flurry of activity to discover similar threats.

"The giggle factor disappeared after Shoemaker-Levy 9," the comet's co-discoverer David Levy is widely quoted as saying, referring to those who dismissed the possibility of such a fate befalling Earth.

In 1996, Levy's colleague Shoemaker set up the Spaceguard Foundation to help coordinate spotting such species-threatening missiles; it collects data from sources both public and private. The name comes from the organization envisaged to serve the same purpose by science seer Arthur C. Clarke in Rendezvous with Rama.

NASA's own Near-Earth Object division is key to this and has a congressional mandate to find all rocks more than a kilometer across in the vicinity – but it's a big sky. According to NASA there are 861 such rocks in the area and 1,378 asteroids that are classed as potentially threatening.

And those are just the ones we know about.

The more we survey the Solar System, the more material we find either floating in slow orbits or whizzing through on their way elsewhere. But funding for such research is pathetically low: NASA got just $5.8m in 2010 to keep an eye out for the end of the world.

The agency has been studying asteroids using probes since the early 1990s, and has launched missions exclusively for studying them. The most recent, the Dawn spacecraft, has already scoped out the giant asteroid Vesta and is on its way to Ceres to check it out as well. Japan, Russia, and China have all sent out probes with varying degrees of success.

What we're discovering is that asteroids generally come in two forms: rubble piles held together relatively loosely or chunks of more sold material that have been blasted out of larger bodies. Comets, meanwhile, are relatively more fragile but usually faster-moving and more difficult to track.

NASA has set the goal of identifying 90 per cent of the Near Earth Objects, and that's a lot of throws of the dice that could turn up snake-eyes. Add in the remaining 10 per cent that we'll miss and it's clear that while we should hope for the best, preparing for the worst is also a good idea.

Better living through technology

It wasn't just the astronomical community that got inspired by Shoemaker-Levy 9. Big bangs always get Hollywood's juices flowing, and the film-going public was subjected to a series of implausible blockbusters about mankind being saved from asteroids – always in the nick of time.

However implausible the films – Armageddon alone has 168 physical impossibilities according to NASA, although it's not known if the agency counted Ben Affleck's attempt to portray believable emotion – they have inspired a generation of boffins to do research on how to deal with such a threat. Based on what's come out so far, we're all doomed.

All current plans currently come down to two tactics: destruction and diversion. One of the first proposed methods was to fire weaponry at an incoming asteroid and either destroy it or blast it out of the way. The tricky part is achieving detonation close enough to the rock to have an effect at insanely fast velocities. In addition, doing so might just turn one big strike into lots of little ones, and add radioactive materials into the mix.

Such plans also underestimate the amount of explosive force needed to destroy a large object or even alter its trajectory. We're talking many times the total world arsenal of nuclear weapons, and that can't be cobbled together in a hurry, nor can the delivery system to reliably get them into the right place.

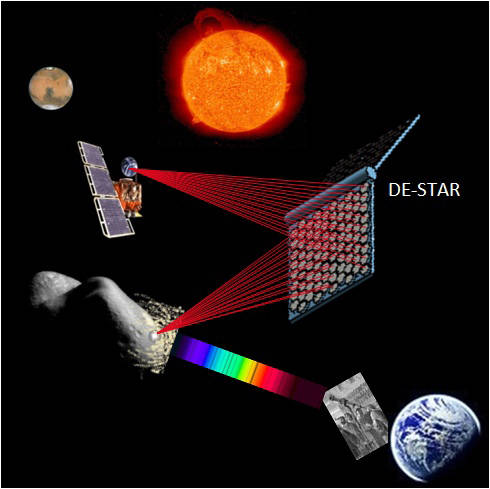

A slightly different technique, and one that could be particularly applicable to comets, is to use orbital lasers to burn away threats before they get here. Comets are typically darker than asteroids and might absorb more energy and thus break apart faster. Targeting a big object isn't so hard, but once it breaks apart that then you're back to the multiple-strike problem.

Lasers might offer one possible, if unproven, solution

The laser approach does look slightly more promising for deflecting incoming rocks, however, by shifting their path an Earth's width or so by heating up the surface. There is, unfortunately, the possibility that as the surface disintegrates then the power of the laser is diffused, and we won't know until such a system is tested.

One recent plan even suggests letting the sun do the job by firing paintballs at the threat, but El Reg would hate to stake the planet on it.

The other type of solution – and the one favored by NASA – is to land on the foreign object and deflect it in situ. This would involve either installing an engine which would fire to change the path of the rock, or install a solar sail to use the sun's energy to change its course.

This would require an effort equivalent to landing a man on the Moon – or beyond, for that matter – and would require reaching the object, matching velocities, landing safely, building and maintaining the apparatus, and then getting off again – although no doubt there would be volunteers to skip the last part, if necessary.

NASA's best guess is that it would take seven years to get such a mission organized. And that's optimistic.

More than one basket

Given the short warning we got from 2012 DA14, the chances of doing anything to stop an impact are vanishingly small. Sooner or later we're going to get hit by something, and if it's big enough the planet could be uninhabitable by humans for years or even decades.

Worse still is the chance of impossible-to-stop impacts like those thought to have caused the creation of the Moon or possibly the asteroid belt. They're highly unlikely to come, but if we're looking to hang around for a few million years or so the odds of living those eons on one planet look short and we'll need a life raft or two, either self-sustaining space colonies or making a go of it on Mars or some of the Solar System's moons.

Science fiction writer Robert Heinlein summed it up best: "Once the human race is established on more than one planet and especially, in more than one solar system, there is no way now imaginable to kill off the human race."

Ever since we've had a space agency, people have been complaining that it's all a waste of money. But getting into orbit and beyond has paid huge dividends in technological advancement, as well as intellectual inspiration, and it will ultimately be the only thing that offers our species a long-term lifespan. ®