Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/01/28/the_oric_1_is_30_years_old/

The Oric-1 is 30

The colourful story of a would-be Spectrum killer

Posted in Personal Tech, 28th January 2013 12:02 GMT

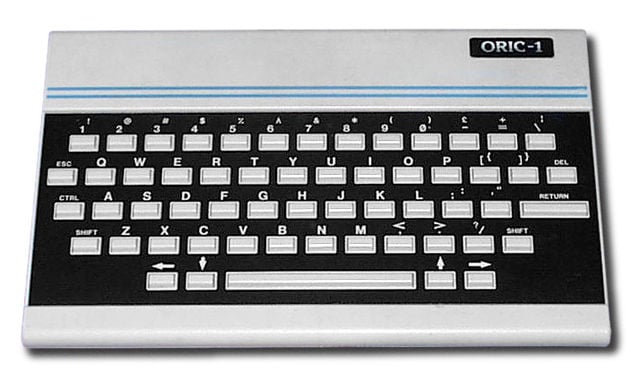

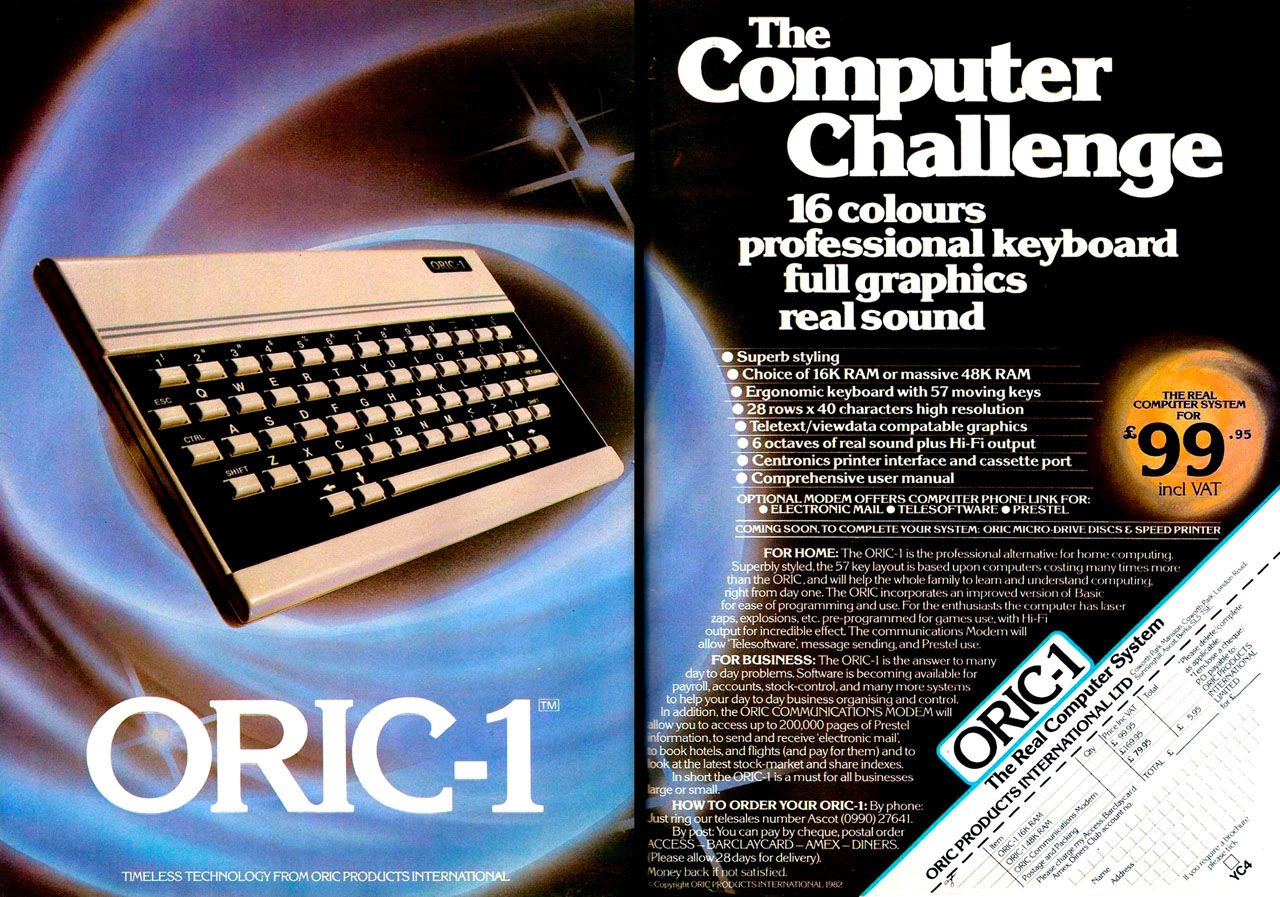

Archaeologic The Oric-1, which was formally launched 30 years ago this week, was produced with one thing in mind: to take on Sir Clive Sinclair at his own game. “The Oric is a competitor for the Spectrum,” one of Oric developer Tangerine Computer Systems’ software team, Paul Kaufman, emphatically told members of the press. “We are convinced that it is a better machine.”

The Spectrum was launched in April 1982 and its arrival brought home to John Tullis, then an executive director dropped into Tangerine by the company’s venture capital funding, that Tangerine’s future lay in the low-cost, £100-200 UK home computer market.

Tangerine was no stranger to the microcomputer arena. The company as it had become by 1982 had been established in October 1979 by Dr Paul Johnson and Barry Muncaster, both of whom were then working for Cambridge Consultants Ltd (CCL), the technology development and consultancy, Johnson as a hardware engineer employee, Muncaster as a PCB layout contractor.

Johnson, whose University of Bradford PhD was awarded for his research into high-speed analogue to digital converters for use in digital television, had already developed an adaptor to link microprocessor test rigs to video display units, which he made and sold to the University under the name Digital Designs in the mid-1970s. Digital Designs soon morphed into Tangerine with the assistance of Johnson’s former school friends Mark Rainer and Nigel Penton Tilbury. They released the video adaptor as the Tangerine 1648 - named after the 16 x 48 character screen it generated - as a side-line while they got on with their day-jobs.

Microtan

In 1977, on the back of the 1648, Tangerine was hired to develop the video sub-system for the Nascom-1 micro then being developed on behalf of Nasco by Shelton Instruments’ Chris Shelton, who had close contacts with CCL. But when, two years later, Muncaster challenged Johnson to prove he could, as he had boasted, develop a full computer and get rich on the back of it for a £10,000 investment, the two acquired the Tangerine Computer Name from Johnson’s existing partners and reformed the company with Muncaster as MD, starting the new version with venture capital funding on 1 October 1979. The following year, Johnson quit CCL to work on Tangerine projects full time.

The upshot was the Microtan 65, a CMOS 6502-based motherboard system designed to slot into a large, rackmountable chassis or one of a series of backplane units, all of which could host one or more expansion boards. In addition to the 750kHz 6502, the Microtan was equipped with 1KB of Ram and 1KB of Rom, the latter containing the system’s monitor softwre, Tanbug, written by a Mike Rose, a pal of Johnson’s who was working for Sinclair at the time. The micro used a UHF modulator to present a 32 x 16 array of 8 x 8 pixel characters on a TV screen.

Tangerine also released the Tanex, an expansion board with space for up to 7KB of additional Ram, tape and serial interface ports, and six Rom slots for extra, system-resident apps, including a 6502 assembler and disassembler, and Microsoft Basic. Other boards, from hi-res graphics units to interface cards, would debut from Tangerine and from third-parties.

The basic Microtan board sold in kit form for £59.95 - the pre-built version was a tenner more, and was assembled by a ten-person in-house team of solderers - and it was aimed solidly at the home computer enthusiast, though Paul Johnson recalls that a fair few were acquired by universities, research labs and commercial entities, among them British Nuclear Fuels.

The 65 was launched in December 1979 and during its first two years on sale it built up a small but keen user base, eventually leading to the establishment of an in-house newsletter, the Tansoft Gazette, edited by Paul Kaufman. “I was a programmer at Shell working on massive databases full of North Seas geophysics survey results,” he remembers.

“I bought a Microtan, and I had problems getting the thing going. I was a constant pain in the arse to Tangerine because I was phoning them up all the time asking questions trying to find out more about how the thing worked. It was quite obvious they didn’t have anyone looking after the customers, just engineers. After I’d been a nuisance for quite I while, they actually called me up and offered me a job of looking after the customers. When I arrived I had six months’ of users’ letters to work through.” Kaufman recalls joining Tangerine toward the end of 1981, but he was being quoted in the press as a company spokesman as early as August.

Tiger, Tiger

Tangerine soon established a software arm, Tansoft, which was later accompanied by Tandata Marketing, set up to sell the Johnson-designed Tantel 170, a gadget for connecting a TV to BT’s online service, Prestel. It’s a device Johnson is still proud of, combining as it did a basic computer, teletext adaptor, PAL signal encoder and 75-1200 baud modem for just £170 plus VAT - at a time when a standard 1200 baud modem would have set you back £1500, he says. By September 1981, Tandata was claiming the Tantel had 78 per cent of the Prestel adaptor market. It then began to offer a version that connected computers to the BT service too. Tandata would eventually be sold, to Applied Petroleum.

In the meantime, Johnson - Tangerine’s sole hardware designer - had begun work on the Microtan 65’s successors. By now, Clive Sinclair’s Science of Cambridge had released the ZX80 and, a year later and under the new name Sinclair Research, the ZX81; Acorn had launched the Atom. All three machines and others of the time, Johnson maintains, contain TV-out circuitry inspired by his pioneering work on the Microtan. But, of course, no secret was made of the machine’s workings: his computer came with full schematics, as all kit-computers did back then.

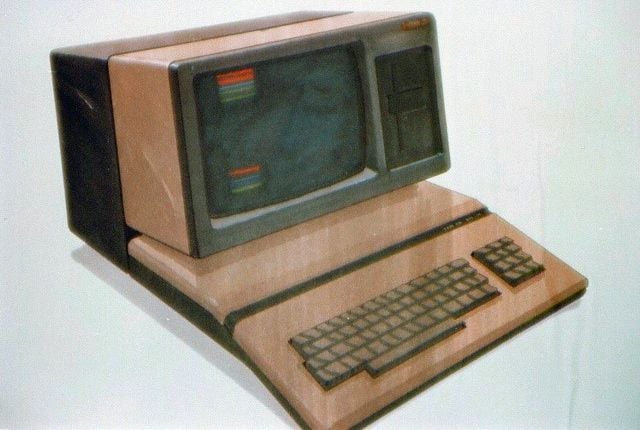

The machine that became the Oric was one successor to the 6502-based Microtan 65, but Johnson also created a larger, desktop system called the Tiger with the intention of breaking into the emerging business computer market, then centred on machines running Digital Research’s CP/M OS. Begun in 1981, the Tiger was a 4MHz Z80A-based machine which had two other CPUs on board, neither of them a 6502. Instead, while the Z80A ran the software, a 2MHz Motorola 6809 was assigned I/O duties and an NEC 7220 handled the graphics work. It had stacks of Ram: 64KB attached to the Z80A for CP/M, programs and data, and 96KB given over to the hi-res, 512 x 512 colour graphics sub-system, plus 2KB for the 6809. The bundled 14in colour monitor unit had space for two floppy disk drives which connected up to two of the Tiger’s three drive controller ports. It also had Centronics and a jack for its built-in modem. With its impressive graphics, the Tiger was aimed at graphical applications, such as CAD, making it a very early example of what became known as a workstation.

References to the Tiger begin to appear in the press in August 1981, but by the spring of 1982, John Tullis decided that the real opportunity in the UK computer market was not for a large desktop machines like the Microtan and the Tiger but small, cheap boxes for games players and enthusiasts. Then Sinclair followed up the ZX81 with the Spectrum, and Tullis suggested Tangerine direct its efforts to devise a low-cost games-centric colour machine to rival it.

Target: Sinclair

The start of the home micro project didn’t mean the end of the Tiger, at least not yet. Come August 1983, months after the low-cost machine had already gone on sale as the Oric-1, Tangerine announced the TD-3000 Tigress with a view to shipping the machine the following October. By then the design had also been sold to HH Electronics, a developer of audio amplifiers founded in the late 1960s and based just down the road from Tangerine. HH announced the HH Tiger around the same that Tangerine did, before putting into production later that summer. HH would take the risk and considerable cost of tooling up for Tiger production off Tangerine’s shoulders.

PCN’s reviewer, Susan Curran, called the Tiger “the Rover of the micro world perhaps”, but the computer failed to make an impression, despite its novel architecture. It was too costly to produce, and Tangerine was never able to ship its version, the TD-3000. HH’s parent company went bust three months later and that was that. Meanwhile, rather than release the micro that was by April 1982 already called the Oric - the name, conjured up by Tullis from a partial anagram of ‘micro’, confirms Paul Johnson - Tangerine instead chose to establish yet another company, Oric Products International, to take the computer to market. A key source of funding for Tangerine’s new computer was secondhand car seller British Car Auctions (BCA), brought in by Tullis, who knew BCA founder David Wickins. Wickins was persuaded to invest in the UK home computer boom and put up £350,000 to fund development work, but this was contingent on the establishment of a new company to market the micro.

Tangerine's early visualisation of the Tiger

From the collection of Paul Kaufman

Tangerine’s role, then, was to develop the machine and license the design to OPI, for which it charged £100,000 up front plus 50 pence per unit for the first 100,000 units, recalls Johnson - £150,000 in all. Indeed, the computer’s motherboard would clearly state: “ORIC-1 Designed by TCS Ltd”.

Tullis became OPI’s Chairman, with Johnson and Barry Muncaster taking on the roles, respectively, of Technical Director and Managing Director. Peter Harding was put in charge of sales and marketing, a role he also fulfilled for Tandata. OPI’s remaining director was Ted Plumridge, present to represent the interests of BCA.

Having designed the Microtan 65 around the 6502 processor - the version of the chip produced by Rockwell - Johnson decided to use the chip in the Oric too. The home micro needed to be developed quickly and cheaply, and that mean using as much of the Microtan as possible.

Designing the Oric

“We stuck with the 6502 processor... because it's probably the world's best-selling chip,” he said in an interview with Popular Computing Weekly published just after the Oric’s formal launch in January 1983. “Besides we have lots of experience with it, and software for it has already been built up. For example, we can quite easily modify the Microtan DOS to run on the Oric.”

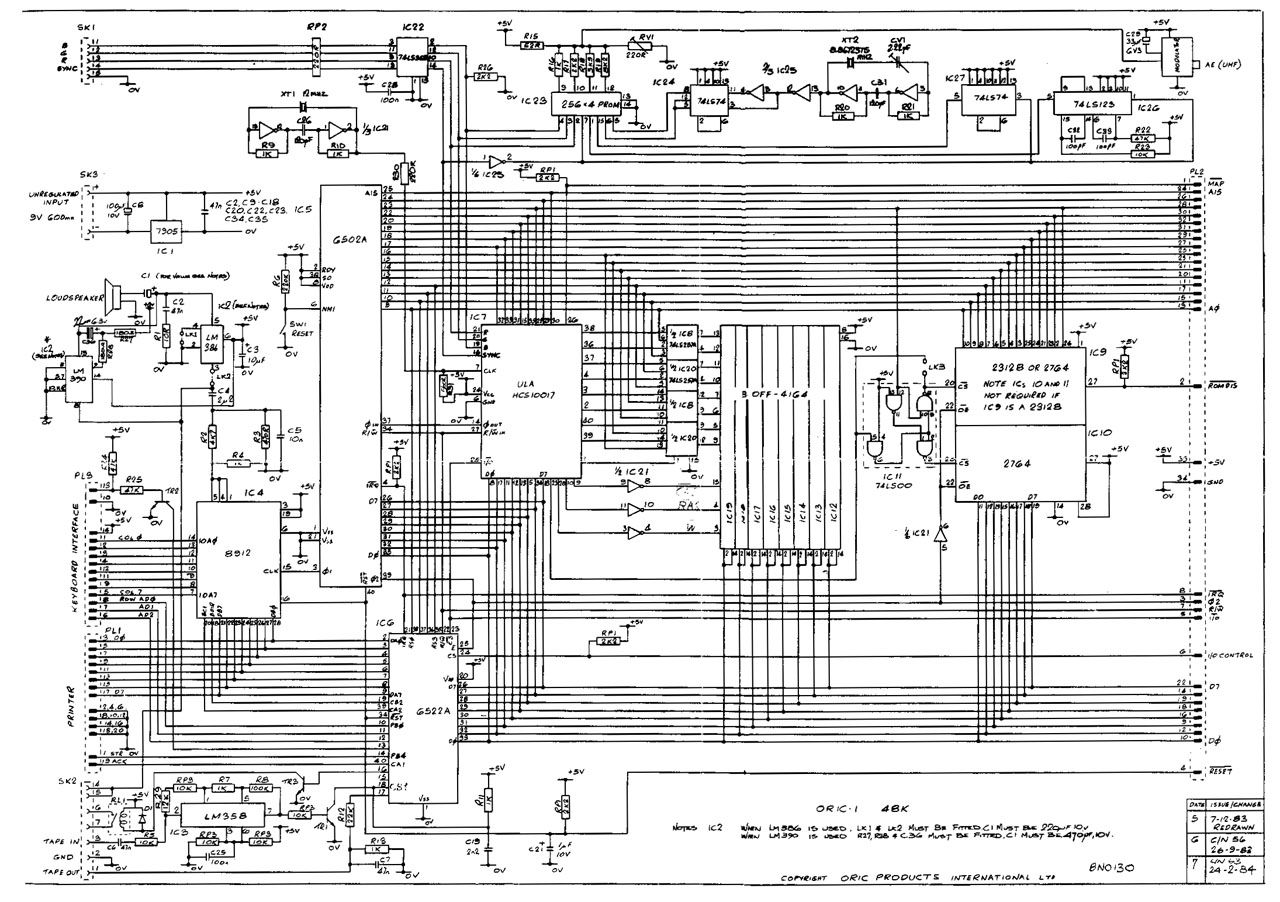

Development work ran through the spring and summer of 1982. In July, Tangerine told the press it had completed the design work on “a new micro which will go on sale in October for less than £100” to take on the Spectrum, which by then had still not shipped in volume and, it was becoming clear, would not do so until the following autumn. Central to keeping down the cost was the use of a monolithic ULA (Uncommitted Logic Array) chip - what today would be called a Gate Array - designed to combine as many subsidiary logic components as possible.

“Incorporating the ULA into the Oric enables the price to the customer to be considerably less than in computers which use generally available chips and processors,” claimed Peter Harding in the June/July 1983 issue of Oric Owner, the by-then rebranded Tansoft Gazette. “The Oric ULA takes the place of 80 chips which would normally be needed to do the job it does.”

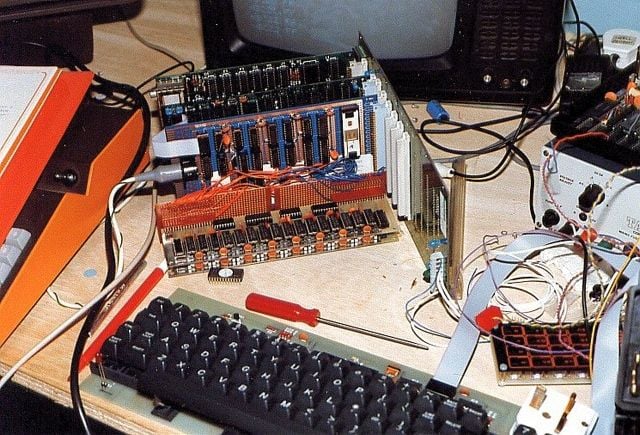

According to Paul Johnson, the ULA was originally created as a TTL (Transistor-Transistor Logic) integrated circuit. “Once you have the TTL version working, you know the logic is OK,” he told Popular Computing Weekly. Tangerine used the TTL ULA emulators in the first Oric build. However, the final machine would use CMOS chippery, fabricated by California Micro Devices - which, in 2010, would be absorbed by industrial chip designer and manufacturer On Semiconductor. “CMOS technology is different from TTL, so we first laid the thing out as a plan to see where the problems would be,” said Johnson in 1983. “Then we did a simulation of a new logic diagram and worked out the timing paths.

“When the first finished gate chips came through from California Devices in early December we took out the emulator, plugged in the chip and it worked first time. It was quite a relief!"

Inside the machine

Alongside the ULA and the 6502 sat a General Instruments 8912 sound chip - audio would prove to be one of the Oric’s strengths, as would the graphics - and a bank of Ram chips, 16KB or 48KB depending on which version you chose. It contained 16KB of Rom. The Rom chip was allocated to the top 16KB of the Oric’s 64KB memory map. The Ram was segmented into, first, four 256-byte pages and, at the top, 10KB of memory for the high or low resolution displays - 240 x 240 pixels and 40 x 28 characters, respectively - and standard and Teletext character sets, copied in from Rom and so editable by the user. In between, sat either 5KB or 37KB for program and data storage.

Connectivity with the outside world was provided not only by the inevitable UHF modulator but also five-pin DIN port to pump an RGB video signal to a monitor, a feature serendipitously added by Johnson because he had some suitable components going spare. This would ensure the Oric-1’s supremacy in France - all it took to support France’s SECAM-format TVs was a cheap RGB-to-Scart cable, which produced better results than the expensive PAL-to-SECAM active adaptors other UK micros needed. A second, seven-pin DIN served as the cassette feed.

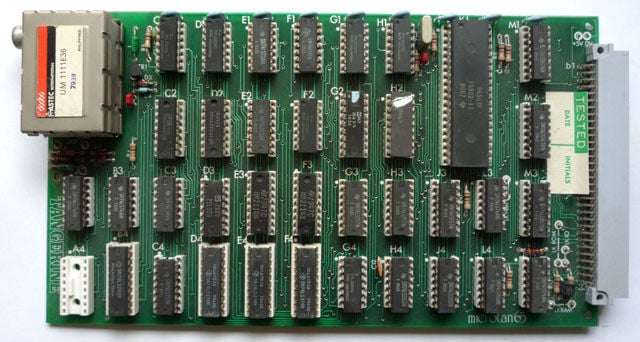

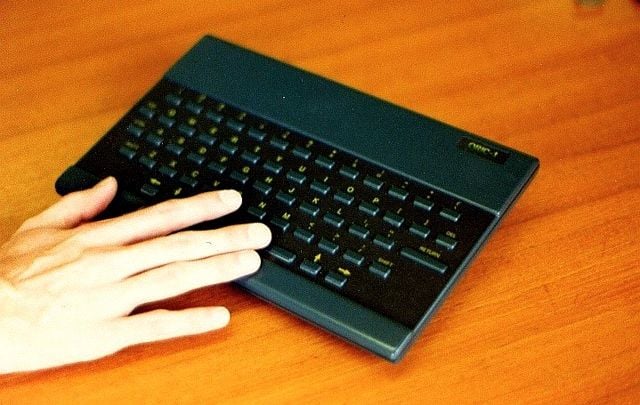

Early Oric prototype hardware

From the collection of Paul Kaufman

“What marks the Oric out from some of the older machines is that it has been designed with an awareness that 1983 will see computers being used increasingly for practical purposes,” said Meirion Jones, reviewing the Oric-1 for Your Computer’s February 1983 number. “The built-in Centronics interface will make it easy to plug in a printer or other peripherals. Oric will soon be selling a modem so that Prestel will become available.”

Tangerine’s own expansion bus port completed the Oric’s port array, set into the back of the machine behind its 57-key plastic capped keyboard, a kind that today might be called calculator-like, but back in 1983 was praised for being not only laid out to make typing accurate but also for avoiding the Spectrum’s rubbery ‘dead flesh’ feel. Unlike the Sinclair machine, the Oric had a space bar. The keyboard, along with the entire casing, was created by industrial designer Paul Durbin, who would go on to style OPI’s later micros.

A troubled start

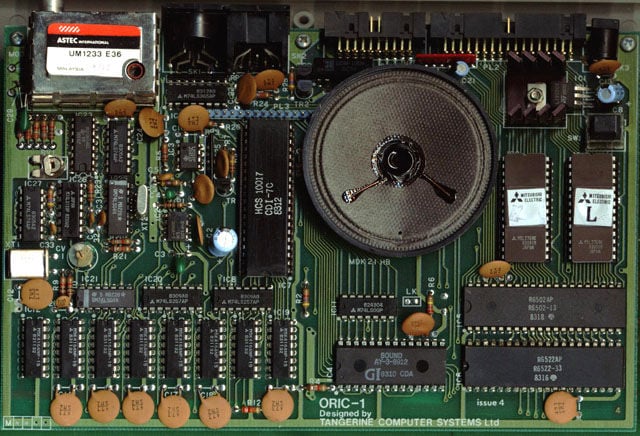

Inside the machine, the Oric-1’s ULA chip slotted into a tidy, well organised motherboard. When Steve Mann reviewed the Oric-1 for the April 1983 issue of Personal Computer World, he was impressed by its “very neat and uncluttered interior... It is clear a lot of thought has gone into the layout; components are neatly arrayed in groups and there are no last minute additions or alterations as there are on the Lynx and the Spectrum”.

That may have been an apposite description of the hardware, but it could not be applied to the contents of the computer’s Rom chip, overseen by chief coder Andy Brown, with Peter Halford assigned to test some of the routines, particularly the cassette handling code. Geoff Philips produced the demo tape. As professional programmer, Paul Kaufman had a hand in it too: he coded the Oric’s sound routines and Basic commands - most notably ZAP, PING, SHOOT and EXPLODE, writing them in Forth before handing them over to the software team to be hand-coded in assembly language on an Apple II.

One of Paul Durgin's Oric case mock-ups

From the collection of Paul Kaufman

OPI originally hoped to begin selling the Oric-1 in October 1982. Early that month, OPI shifted the release date back a month, announcing that it would debut in two versions: a £99.95 16KB model and a 48KB unit for £169.00. The cheap machine was immediately heralded as the first UK colour micro available for under £100.

Come November, however, and an OPI admitted that its initial batch of 1000 machines would now not be released until mid-December. Unfortunately, it had begun advertising the machine and soon started taking orders - 2000 of them by late January 1983, according to the company. By way of compensation, the 48KB machine would now come with Forth as well as Basic, it said, the former on cassette. A 32KB model was announced too, priced at £139.95, though this version, if it was ever seriously considered, never made it to market, a victim of the need to deal with a TV modulator problem that was holding up manufacture of the 16KB and 48KB units.

According to Steve Mann, writing in February or March 1983, PCW received its first Oric-1, a pre-production unit, on 23 December 1982. It didn’t work, and neither did a replacement unit. A third Oric worked, but came without usable documentation. PCW would eventually receive the manual and a fourth Oric to test. Other reviewers were less lucky, ensuring “reviews have already appeared in some magazines that will have dissuaded a large number of prospective purchasers from buying. These reviews have contained wrong information and have failed to mention any of the Oric's strong points. This is no reflection on the journalists involved - there is no way they could have done a proper job without the material provided”, wrote Mann.

Manual override

“The stupid thing about all this is that the worst sufferer of the debacle has been Oric itself... It would have been far better if Oric had held back on the hardware (and the advertising) until the full manual was ready...”

That fact seems to have been lost on Oric’s managers, some of whom took the early reviews personally. Peter Harding, for instance, grumbled to Oric Owner that “the general standard of reporting is diabolical and there is more inaccurate information printed than actual facts. The reviews... of the Oric, although in the main very favourable, are often totally inaccurate and do not extol the full virtues of the Oric, eg. only two colours in hi-res mode.”

As Steve Mann noted, proper documentation might have prevented that.

To be honest, OPI was not unique in this. Many a new computer company rushed to commission manuals while the hardware and software were still being worked on. Getting to market quickly meant there was no other way. The Oric-1’s final manual would eventually be sourced from Popular Computing Weekly and computer book publisher Sunshine.

OPI wasn’t alone in suffering supply woes, though suffer them it did. “It would be unfair to single out OPI because many of the people who have now waited three months for the Orics they ordered on 28 days’ delivery only ordered one because they had given up on ever receiving the Spectrum they had ordered when Acorn failed to deliver the BBC on time,” quipped Your Computer’s Meirion Jones in the February 1983 issue

Supply problems would dog OPI throughout the first half of 1983 - video issues delayed the production of both models into February, and for a time it seemed that the 16KB Oric would go the way of the 32KB version. Some folk who ordered 16KB Orics were even lent 48KB machines in lieu of the arrival of their chosen models, so clearly OPI could make enough of those. Eventually, Barry Muncaster told readers of the June/July 1983 issue of Oric Owner that 16KB Oric-1s “are now in full production”, some “minor technical problems” having at last been ironed out.

Not-so-sweet 16K

“The 16K Oric [was] exactly the same design as the 48K Oric,” said Muncaster. “We would have had no problems if the specification of a particular chip had not altered just prior to manufacture. However, it did, which resulted in us having to change the 16K circuit board. This has meant a 12-week delay in production.”

It has been suggested that cost was also a reason for the 16KB Oric’s delay: OPI couldn’t make it cheaply enough to justify the £99.95 price - the 16KB Spectrum was £125, and that’s with Sinclair’s undoubted savvy in low-cost manufacturing. “It is costing so much to build the 16K that we cannot give a decent discount,” Paul Kaufman told Popular Computing Weekly in March 1983. He was explaining why OPI’s retail partners were focusing on the 48K model, but his words hint at what may have been the real reason for the 16K no-show. “Later on in the year, production costs may come down and we will be able to offer a better deal.”

Indeed, in May, the 16KB Oric went from £99.95 to £129.95, though OPI bundled £30 of software with the machine to take away the sting. Smart it did - at this time, most other micro makers were cutting their prices, Sinclair having lead the way in April by aggressively dropping the 16KB Spectrum to £99.95 and the 48KB model to £129.95. For a time, then, Sinclair was selling a sub-£100 colour micro and OPI was not.

Eventually, OPI began to get on top of the matter. Marketing director Peter Harding said in the same issue of Oric Owner: “During February we made and sold 25,000 units and May's figure was 32,000 units. All of our mail order sales will be fulfilled by the end of April, and the Oric will be available readily in WHSmiths, Dixons, Laskys, Menzies, Spectrum, Computers For All, Greens (Debenhams) Micro C and hundreds of independent computer dealer outlets.”

Looking ahead, Harding forecast that “Oric expects to sell approximately 400,000 units to February 1984 to be sold in the UK and Europe. This figure does not include the considerable product we expect to be sold in Japan, SE Asia, Australia/New Zealand and the USA”.

Rom problems

And sell the Oric did, especially over the Channel in France. There, some 35,000 machines had been sold by late September 1983, according to one contemporary report citing OPI, more than the 21,500 sold in the UK. Overall sales were around 72,500 units.

And this despite some early reviews’ errors and some serious issues. Cables were found to fit poorly, most notably the power line: a slight knock and the Oric shut down for want of electricity. Then there was the Basic. Early machines booted into “Oric Extended Basic 1.0 © 1983 Tangerine”, according to the computer’s start-up screen, and the first users found it to be rather buggy. “In the first systems IF... THEN worked but IF... THEN... ELSE didn’t unless the first statement in the ELSE clause was a PRINT statement,” noted Personal Computer News in its 29 April 1983 issue, adding that a fixed Basic was due in “weeks”.

“The faults in the Basic language have been tracked down and corrected,” Barry Muncaster told What Micro? early in 1983, referring back to reviewers’ grumbles. “A new ROM has been ordered and should be in all machines leaving the factory after the start of April.” If the PCN report is anything to go by, that didn’t happen - or if it did, it left a fair few issues unresolved. By October Oric sources were telling Home Computing Weekly that this “new Rom will make cassette handling and the TAB command more reliable” - both problems that went back to the early Roms.

The cassette routines were widely criticised in the early days, with bundled software tapes often failing to load no matter what cassette player was used. OPI blamed Cosma, the Witney, Oxfordshire based company that duplicated Oric’s cassettes. “There was a technical problem with the tapes,” said Paul Johnson at the time. “The problem was purely down to the quality of the duplication.”

Taped out

Cosma denied the claim and insisted Oric’s hardware was to blame. “The Oric machines appear to have a problem. We test our production rigorously, and our data duplication company is one of the highest quality,” said a Cosma representative. “We can take any sample Oric likes, and load it.”

Wherever the fault lay, it was Oric owners and coders who had to deal with it. At October 1983’s Personal Computer World show, software developer Softek showed off an Oric Basic compiler which it said would ship by Christmas. OPI was tight-lipped, but many users crossed their fingers and hoped this meant a bug-free Basic would be with them by the festive season. To date, OPI had chosen to reveal very little to machine code writers about the Oric Rom’s routines, claiming it software licence prevented it doing so and that changes might invalidate published information, breaking code written on the back of it.

Paul Johnson reveals that Tangerine was not merely an early licensee of Microsoft Basic, but that it also owned an OEM licence allowing it to sub-license the code, which it did, to OPI. Both Johnson and Paul Kaufman recall that Microsoft’s code, supplied as source files on a floppy, contained many bugs which OPI’s software team had to fix. The glitches were duly reported back to Microsoft, which ignored them until Barry Muncaster threatened to withhold future instalments of the licence fee. “After that, we got a letter from Paul Allen telling us ‘Bill was on the case’,” recalls Johnson.

Meanwhile, the cost of ramping up production, and of developing promised disc drives, a modem and a printer, all of which had to be delayed a number of times - from June to September and then on into 1984 - was burning through OPI’s funding. It was growing too big, too quickly.

Chairman John Tullis said at the time he foresaw the problem in the Spring of 1983 and began seeking new funding. In October, he announced that Edenspring Investments PLC, a property speculator, would acquire OPI in order to bring in fresh finance to help cover OPI’s growing R&D costs and its plans to expand into new areas of business, and to clear debts.

Edenspring

“Because we are increasing our trade so rapidly and going into a number of new products in 1984 we have had to widen our capital base to finance the developments. We would not have been able to fund that ourselves,” Tullis told the press and punters. He revealed the deal would give Oric the cash it needed to expand its business for 12 more months, and OPI spun the investment the basis for growth. But Peter Jones, Edenspring’s joint MD, revealed that “Oric’s cash requirements are, well, quite pressing”. The reverse may have been true too - Paul Johnson recalls that, after the deal was struck, the shine came off a number of Edenspring’s property holdings.

The acquisition saw Edenspring offer OPI’s creditors shares to cover £1 million in debt, and the release of further shares to raise £750,000 in cash. Outside of OPI, the move was viewed as a sign the company was in difficulty. But Johnson says the Edenspring deal was partly inspired by Acorn’s September 1983 flotation on the Unlisted Securities Market (USM): rather than float OPI, a costly process, it was cheaper to have Edenspring, which was already listed, buy the company.

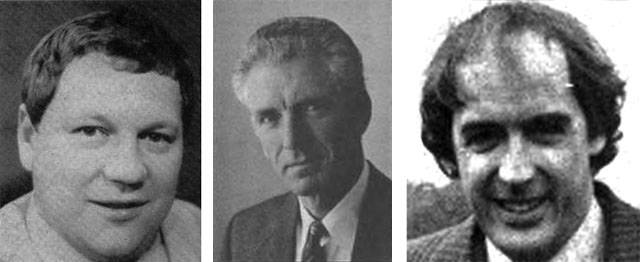

OPI dramatis personae: (L-R) Peter Harding, John Tullis and Barry Muncaster

Stock Exchange rules, however, meant Edenspring lost its listing, forcing the shares to be traded on the less prestigious private over-the-counter market. At the time the scheme was announced, Edenspring shares were trading at 9p each, valuing OPI at £8 million.

One casualty of the Edenspring acquisition was the temporary shelving of plans to introduce a IBM PC-compatible micro, presumably for cost reasons. Barry Muncaster signalled the scheme during September 1983 in response to ‘Peanut’, a version of the PC IBM was developing for the home market. Oric’s machine was to have been priced at £200, Johnson recalls. Eventually the Big Blue machine would be released in November 1983 as the PC Jr. Cheekily inverting the story, Muncaster told Popular Computing Weekly that “Oric will produce a product which the Peanut will be compatible with”.

He also forecast that “Peanut will be very successful”, which also proved to be the exact opposite of what eventually happened. The PC Jr, Time magazine later wrote, “looked like one of the biggest flops in the history of computing”.

Fire in the hole

Worse luck came sooner: Kenure Plastics’ Berkshire factory, site of Oric-1 production, was consumed by fire on the night of 13 October, wiping out stocks of finished Oric-1s - around 7000 - and unassembled components. Production began again at a nearby facility almost immediately, but it was news OPI and Tangerine could have done without.

Still, the following month, OPI told the world it had shipped 120,000 Oric-1s - fewer than half the 350,000 Oric Owner’s June/July issue claimed had been ordered during the first half of the year - and that it expected to record sales of more than £10 million by January 1984 “putting Oric in the top league of British home computer makers”. Weekly sales data produced by research company MRIB show the Oric-1 rising from fifteenth place in the Top 20 Sub-£200 Micro Chart to peak at number three at the start of May. Over the coming few months it was drop to eighth place but then rise again, to fifth, overtaking at times the ZX81, the Vic-20 and the Dragon 32 but never really challenging its arch-rival, the Spectrum.

OPI’s ambitions stretched beyond micros. “In addition to sustaining growth in the volatile home computer market,” the company said, “Oric is broadening its product base into business communications and opto-electronic systems which are being developed at its new 11,000sq. ft. Cambridge R&D centre.”

John Tullis said at the time: “I intend to widen the company’s product base and it is hoped that within two years computers and peripherals will form no more than 50 per cent of our business.” Paul Johnson recalls the establishment of a new company, Oric Medical, to devise technological products for clinical settings, including a gadget for reading blood pressure through a fingertip sensor.

Making that possible was a further £4 million from Edenspring which, having made its initial investment, now swapped OPI shareholders’ Oric stock for its own shares, named Barry Muncaster MD and put Tullis on its board, neatly completing OPI’s reverse acquisition of the firm. The firm had great hopes for 1984.

Yet the Oric-1’s days were numbered. Conceived in April 1982, formally launched in January 1983, it would be succeeded in January 1984 by the Atmos. At the 1’s launch, OPI Marketing Manager Peter Harding had talked about a successor machine appearing in 15 to 18 months’ time, and, by March 1984, 15 months after its formal launch, the Oric-1 was indeed no longer in production.

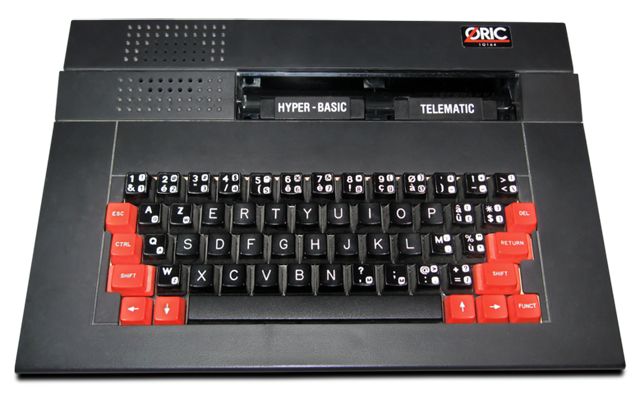

Atmos

The Atmos’ arrival was somewhat overshadowed by the debut of the QL, Sinclair’s attempt to break out of the home computer market into the more lucrative business arena, as Tangerine had once dreamed of using the Tiger to do. But the new Oric wasn’t much of an upgrade: the Atmos was simply an Issue 4 motherboard Oric-1 in a new case - once again designed by Paul Durgin - that featured a bigger, but not, admits Paul Johnson, better, keyboard. It also shipped with, at long last, a fresh Rom, version 1.1. It still contained some issues, but the worst version 1.0 bugs were squashed.

Yet the Atmos wasn’t the new machine many Oric fans had anticipated. “I don’t see how anyone can call the Atmos a new product,” grumbled Your Computer reviewer Bryan Skinner. It’s no wonder then, that by February 1984 Barry Muncaster was already talking about a successor - “the likely name is Stratos”, reported PCN - a third Oric machine that, it seemed, would be out before the peripherals - modem, disk drive and printer - promised would accompany the first in the series.

Users had to wait until October 1984 for the modem when, as Personal Computer News tartly put it: “Oric has produced the micro world's equivalent of proof that the Loch Ness monster exists - it has released a modem.” This despite OPI telling the world the previous March it had canned the product...

The Stratos - at least, the machine Muncaster had hinted at - likewise took some time to emerge. OPI talked up the Stratos - aka the IQ164 - in December 1984, but it was largely an upgraded Atmos, itself a revamped Oric-1. Only two Rom cartridge slots, one for the Basic interpreter or any other language, the other for applications, marked it out from its predecessors. It would appear eventually as the Telestrat, released in the latter half of 1986 by Eureka Informatique, the French firm that acquired OPI “for several hundred thousand pounds” in May 1985.

Christmas 1983’s lower than expected home computer sales hurt many a UK manufacturer. It contributed to the demise of Dragon and of Lynx creator Camputers, and almost did for Acorn. But 1984 proved an even tougher trading environment indeed, thanks to declining demand for home micros and a fall in the Sterling-Dollar exchange rate driving up the cost of components - the prompted OPI to up the Atmos’ price by £20 to £190. More computers were being sold through the major chains, which demanded lower and lower prices, crushing vendors’ margins.

Many folk thought Oric would not survive 1984. Finance Dir Allan Castle was repeatedly called upon to deny the company was in difficulty. In August, he claimed sales were running at £2m a month after record sales of £2.5m for June. Toward the end of the year, Barry Muncaster boasted Oric/Atmos sales had topped 350,000 units in the first two years - “by then Sinclair hadn’t got round to the ZX81”.

The beginning of the end

Legal action hounded OPI throughout the year. Pan Books sued over alleged non-payment of fees for the production of the Atmos manual; OPI sued its new, exclusive distributor Prism for £4m - it was awarded £320,000 - after unsuccessfully attempting to sue KMP, its advertising agency, for the same amount. Durrell Software had a go too, and Teknocron Circuits tried to have Tangerine Computers Systems - seemingly dormant for the past two years - wound up, claiming TCS still owed it money for making the Tantel 170 boards.

During 1984, John Tullis stepped down as OPI's Chairman, to follow other business interests. He was replaced by Edenspring chairman David Duguid.

OPI formally launched the Stratos just over two years after the Oric-1, on 1 February 1985, but this time it went into receivership almost immediately - and before it could launch the two IBM compatibles it had suggested in November 1983 it was working on, not to mention the MSX box and 68008-based QL killer it talked up separately. "We could solve Acorn's problems at a stroke," boasted Muncaster.

Maybe, but he couldn't fix OPI's woes. Edenspring put the company into receivership on 2 February 1985, "after months of speculation", as contemporary press reports put it; new Tansoft chief Bruce Everiss said: "Oric has been looking over its shoulder at the receiver for about six months now."

Oric survivors today: Paul Johnson (inset) and Paul Kaufman

Everiss was made redundant; Barry Muncaster resigned from OPI and Edenspring and took over the management of Tansoft. For a time: Tansoft went under in May. OPI’s debt was estimated at £5.5 million. ASN, OPI's French distributor put in a bid for OPI, but it was rejected. So was a bid from Muncaster. Eureka picked up the pieces shortly afterward, and OPI continued not as an English company but as a French one - appropriate, since its machines had always been more popular there. Eventually, Eureka, which restyled itself Oric Products International, crashed too, in December 1987.

OPI’s closure in the UK saw the departure of Paul Johnson and Barry Muncaster. Johnson went on to establish a number of semiconductor design consultancies, including Array Consultants and Energys, and went on to acquire and run Cambridge Consultants’ fabless semiconductor company Cyan. He’s now a consultant advising semiconductor and electronics start ups and investors. Muncaster eventually took on a number of senior roles in the biotechnology industry.

Peter Harding died in 2004. Paul Kaufman quit Tansoft toward the end of 1983 to found Orpheus, a multi-platform software developer, and later ran LanSource. These days he’s in charge of music-computer kit maker IK Multimedia’s UK sales operation. His successor at Tansoft, Bruce Everiss, went on to become marketing chief of Codemasters, organised the All Formats Computer Fairs, and now is in charge of communications at Kwalee. ®