Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2013/01/02/monitor_2000ad_mach_1_and_forecasting_future_tech/

Making MACH 1: Can we build a cranial computer today?

How SF gets it right by getting it (mostly) wrong

Posted in Personal Tech, 2nd January 2013 12:43 GMT

Monitor is an occasional column written at the crossroads where the arts, popular culture and technology intersect. Here, we look back at 2000AD's MACH 1 - the first secret agent with his own, in-body computer.

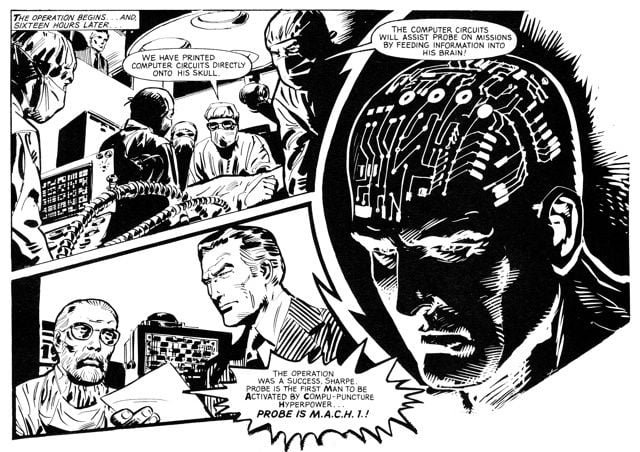

In 1977, Pat Mills, the first Editor of 2000AD comic, created MACH 1, a strip telling the story of John Probe, a super-powered cross between James Bond and the Six Million Dollar Man. These days, most fans of the strip remember the Man Activated by Compu-puncture Hyperpower for his enhanced, bionic-level strength, but Probe had another McGuffin: a computer grafted onto his skull.

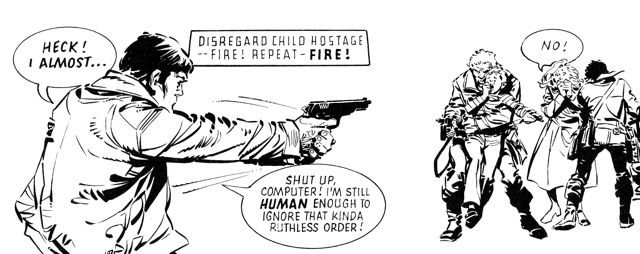

Probe’s up-close-and-personal computer - known affectionately as ‘Computer’ - could hear the secret agent ask it questions and was programmed to respond with mission-relevant information.

Back in the late 1970s, this was pure sci-fi. There were desktop computers in the States, and they were starting to appear over here, but the idea that any of 2000AD’s readers would have one of their own, let along one small enough to fit inside the human body, was fanciful in the extreme.

And yet four of five years later, thanks to Sinclair, Acorn, Commodore, Dragon and co., many Earthlets did indeed own a computer at home. Now, almost 36 years on, as gadgets from the smartphones we all have in our pockets to the likes of the Raspberry Pi demonstrate, computing power can now be placed in a very small space indeed.

So could we create a MACH man’s cranial computer today?

It’s not beyond the bounds of possibility. Probe’s computer could speak and hear. Speech synthesis is a doddle to do, and if the output is fed through a tiny speaker tuned to a frequency that will make the user’s earbones resonate - a technique that’s been applied to audio output since the late 1970s - our modern day MACH man would be the only one able to hear it. Fit a tiny microphone into his voicebox and he’d be able to answer back, speech recognition software doing the hard work.

The circuits of Probe’s computer were applied directly to his skull. In at a time before World+Dog knew what a silicon chip was, 2000AD’s artists envisioned the computer as being comprised of electrical lines and bulk components. Laying down layers of flat copper circuitry onto the curved surface of the skull would be tricky, but not impossible. CAT scans would allow a precise model of the subject’s head to be prepared. The circuitry could be fitted to that before being placed on the real skull.

Getting the chips in place would be harder, not to mention leave a series of bumps and lumps under the skin. But it’s not hard to envisage removing an area of bone during surgery and replacing it with a 3D-printed unit containing circuitry, memory, solid-state storage, processor and I/O. Hook it up to the aforementioned mic and Bonefone-style resonator, and you’re away.

Well, almost. We still need power. How about a wee - and well-sealed - thin lithium polymer battery kept topped up by a gadget for converting kinetic energy from our MACH man’s movements into electricity? You know, the kind of rig that keeps watch springs tightened. Such a system was proposed for phones and music players a couple of years back.

Of course, this being a lithium battery, our hero’s bosses in the SIS - modern day equivalent of the slimy, xenophobic Dennis Sharpe - would need to ensure the power pack can be eventually removed and replaced. That said, given the kind of scrapes the original MACH 1 got into, perhaps his non-hyperpowered successor wouldn’t last long enough to need a new battery. Assorted off-the-shelf bio-sensors would allow the computer to track the state of MACH 2013’s physiology.

The Modern MACH Man

So there we have it: the ultimate in wearable computing, a compact, subcutaneous computer able to communicate by speech. This being the modern age, of course it would have wireless links too - cellular for range and ubiquity - for interrogating remote databases plus GPS to keep our secret agent on track to his destination and to find the quickest escape route. Again, all this is possible now: we have the technology, we have the capability.

The question is, of course, whether our man would need it at all. The very technology that would allow a computer to be miniaturised and embossed on a secret agent’s skull as per the original MACH 1 is already there in his hand: it’s his phone.

Give him a hands-free headset and a feed from base, and he can be continually aided by humans at home who can monitor his progress using military grade GPS tech and, at least while he’s outdoors, satellite-mounted cameras. Modern agents don’t need to undergo expensive surgery to get real-time data feeds - just a trip to a local Carphone Warehouse.

That’s the trouble with looking ahead an wondering how technology might evolve. Writers often get the broad thrust right - as Pat Mills did, anticipating the miniaturisation of advanced compute power - but when it comes to details they are usually out by miles. They’re interested in what we can’t do now but would like to. But they forget that it’s the technologies we discovered but didn’t know what they might make possible that change the world.

Take the microprocessor. Integrating circuits is one thing, and a necessary step toward the greater miniaturisation of electronics, but using the technique to create a programmable logic device that, at first, was less powerful than any computer of the time... well, no wonder Intel, back in the 1960s when the first microprocessors were being created, thought its future lay in memory chips. Even if the company could have foreseen the personal computer revolution, and perhaps made the logical leap off the desktop and into users’ hands, would it have conceived a world just 50 years hence when people own laptops, desktops, tablets and smartphones, all of them general purpose computing devices?

Pat Mills at least envisaged an interesting new form-factor: the cranium. Of course, he created MACH 1 to entertain ten-year-old boys, not forecast the future. John Probe’s computer ally is a plot device first, prediction second, and an unintentional one at that. Post World War II science-fiction is rarely deliberately predictive. Any fiction set in the future is going to make implicit predictions about what technology humans will be using at that time, but it’s important not to forget that these ‘forecasts’ are first and foremost tools to help tell a story.

Whether forecast

Think about Star Trek, perhaps the most enduring example of SF widely believed to be intentionally predictive, especially by Americans working in the technology industry, most of whom seem to be Trekkies. The show’s Communicator is held by some to be a mobile phone prototype, but it’s really just a futuristic walkie-talkie. There’s no indication everyone in the Federation or beyond possesses such a device and uses it not only to talk to people over great distances but to read the news, play games, to navigate on foot, to tell other folk what they’re currently doing, and to take pictures. Star Trek: The Next Generation may have miniaturised the Communicator into a badge, but it’s still just a voice device, not a smartphone.

Not to pick on Trek - few novels, comics, films or TV series forecast what mobile phones have become and their impact on today’s society let alone tomorrow’s. Those that hinted at widespread phone use didn’t see text messaging coming or - despite the Sony Walkman - that we’d be downloading music to them. Most SF authors who got wind of the internet in the 1970s and 1980s didn’t suggest we’d be turning to it on mobile devices for daily news and telling World+Dog in 140 characters or less what we’re doing at any given moment. There is no Twitter, no Facebook in William Gibson’s early novels, for instance.

Just like MACH 1’s cranial computer, it’s easy to come up with ‘impossible now, possible sometime’ technologies, but rather harder to work out whether they’ll find a use - and even more to spot other technologies that make them redundant. ®