Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2012/11/28/the_bbc_news_online_story/

Scoop! The inside story of the news website that saved the BBC

How BBC News Online was created from scratch

Posted in Legal, 28th November 2012 11:20 GMT

Special report Fifteen years ago this month the BBC launched its News Online website. Developed internally with a skeleton team, the web service rapidly became the face of the BBC on the internet, and its biggest success story – winning four successive BAFTA awards.

Remarkably, it operated at a third of the cost of rival commercial online news operations – unheard of in public-sector IT projects. Devised before there were really any content management systems, the technical architecture became a template for all major news systems, and one that’s still in use today. The team endured some furious internal politicking and sabotage to survive.

Here for the first time is the inside story of the website that saved the BBC – with contributions from key figures including former BBC director general John Birt, now Lord Birt.

The BBC reports its award-winning BBC site

Why the internet?

When the information superhighway arrived on a wave of hype, there was good reason to be sceptical. Dialup computer bulletin board systems (BBSes) had been around for a decade albeit with limited adoption from enthusiasts. The French version of Prestel, Minitel, had only reached its wide audience of about 9 million homes because the French government had subsidised the terminals. The internet remained just as expensive, at UK dialup rates, as the marginal BBSes.

“A senior news editor told me the internet would be a flash in the pan – this was in 1996,” recalled one BBC correspondent. When it was clear it wouldn’t, it was argued it would confuse people.

Another Beeb journalist, Mike Smartt, who was an early enthusiast of the online service, said: “Putting web links on TV would merely bamboozle viewers, they argued. Announcing them on radio news would be worse and take up precious time."

Fortunately, one BBC figure fascinated by digital technology was best placed to ensure the online operation could take off: Lord Birt, the director general of the corporation, who was an Oxford engineering graduate. At a grammar school in Liverpool in the late 1950s, he had been given a project to explain the difference between analogue and digital computers to his science class.

“I didn’t find a use for that knowledge for twenty five years,” he now chuckles.

Lord Birt had been trumpeting the impact of new technology, such as fibre-optic networks, and how it could dramatically lower the barriers to entry: TV could become a read-write medium, he pointed out in a 1979 lecture.

Although the newborn internet was on the Beeb's radar from early on, no one knew exactly what to do with it. There was a desire to explore it, Lord Birt told us, but “this was quizzical, curious and inchoate – it was a very long time before that coalesced into anything you'd call insight”.

For Lord Birt, the 'net looked like “a way of sending rather dry-looking text around the world speedily and it did feel all very techie – this wispy blue print, no pictures, no graphic design, certainly no moving pictures. No real impact. It felt like the kind of medium you'd use to send academic papers to a foreign university”.

Lord Birt

“This is a medium in which you can transmit news – but in what form – and to what market – these were things we didn't know the answer,” he told The Register.

In the summer of 1996, the BBC had signed a deal with Fujitsu ICL. For £50m, the computer giant acquired the right to use BBC material and build its websites – including a news service. The sites would use Fujitsu ICL software, under shelter under the umbrella domain Beeb.com. The service would be funded by advertising.

Lord Birt explained the thinking:

The early but faulty insight was that the internet was an extension of the world of publishing. What part of the BBC published magazines? That was BBC Worldwide. And we couldn't see, at that point, any real prospect of utilising the technology. That plainly was a mistake.

But then the DG had second thoughts. Serious second thoughts.

"The story has many heroes and one is Jeremy Mayhew," said Lord Birt. Mayhew had been an advisor to the MP Peter Lilley, who was a member of the Tory Cabinet in the early 1990s, before joining the BBC Strategy Unit in 1993. He became the director of new media two years later.

“He was the one who did the deal with ICL which was very much again a piece of venturing on both sides,” added Lord Birt. “In life sometimes you make a decision instantly – I looked at Mayhew's [online news] prototype and” – the peer clicks his fingers – “I saw what the implications were. I saw we had made a big mistake and that we needed to do a U-turn – and it was unthinkable you could put that service like that out with advertisements.

“All of those thoughts occurred to me in half a second – and all credit to Jeremy for the work – all of those things became instantly apparent.”

Lord Birt decided he had to take the news website out of the Fujitsu ICL deal: the BBC must own its own internet news site.

“That was really bad news for ICL in some ways although they still had the ability to participate," admitted Lord Birt. Rumours of a lawsuit never materialised. The fine print in Mayhew’s contract with the computer giant kept the BBC in the clear. (Beeb.com would eventually be repositioned as a shopping portal before it was closed in 2002.)

The BBC’s R&D wizard Brandon Butterworth – “another hero”, according to Lord Birt – “was someone who had all the equipment needed in his bedroom”. Butterworth had already put up the first website from Kingswood Warren, the sprawling Surrey mansion that housed the BBC's research team. And the BBC had even briefly operated an internet service provider called the BBC Networking Club.

BBC Online, separate from the news website project, was established as an experimental area. After some investment, it fell under the control of former Tomorrow’s World producer Ed Briffa, who reported to Broadcast – the TV and radio empire that was historically at loggerheads with the BBC’s news departments. BBC Online had little clear vision of what it should do – but then few people in the mid-1990s did.

Some 12 years before he became a life peer, Lord Birt joined the BBC in 1987 as deputy director general. He arrived from ITV with a brief to sort out news and current affairs, and hand-picked two journalists in their 30s – Tony Hall and Jenny Abramsky – as lieutenants to lead his revolution. A decade on, Hall was director of news, and Abramsky head of the awkwardly-named "continuous news".

Bob Eggington

Abramsky sounded out Bob Eggington, a tough and practical editor, described in Lord Birt’s memoirs The Harder Path as a “dedicated, driven and no nonsense journalist” to head up the news website project.

Eggington wasn’t sure about it. He knew the corporation was on rocky ground – but he knew that if the operation could be built quickly and did a good job, its momentum might overcome corporate inertia and win over doubters. He secured a direct line of command to Abramsky and Hall – and a promise to shield the operation from the BBC’s bureaucracy. This would prove invaluable.

Mike Smartt joined as the news site’s editor. He had been a BBC TV news correspondent at home and abroad – and was an early technology adopter. He’d demonstrated to management that he could file scripts on a laptop “without harming himself or anyone else”. Smartt was fresh from the BBC’s 1997 Election website. For Eggington, Smartt “had thought about doing a news website longer than anyone else – and knew more about it”.

Lord Birt was famous for insisting that vast, deeply analytical reports are produced before any decision could be justified. When it came to the internet, he made the decision to ramp up online activity, then commissioned the reports later – and he was right. As one BBC insider put it: “Birt saw that something needed doing, so he set up something with the freedom to do it."

Eggington told The Reg: “He has his detractors, and sometimes I'm one of them, but the whole BBC internet effort happened because of John Birt.”

The peer is more modest today and deflects credit onto others.

“The BBC is a delightfully creative organisation: whether it's well managed or badly managed, these people will express themselves,” he said. “People were broadly alert to the internet. But they can't coalesce, so to speak, unless the management stands behind it and invests in it.

“We didn't act perfectly on every insight we had – but the news demo was the critical moment – I knew this is going to be an important public service medium, and it has to be funded by the licence fee, and it's going to be very successful. And we've got to be there, and be pioneers.”

There was a snag, however. The BBC wasn’t allowed to put up web pages. Nothing in the royal charter – which sets out the public-funded organisation's purposes – permitted it to do so, and the Ministry of Fun was ready to pounce on any transgression. The lacuna threatened to paralyse the BBC’s operation. Lord Birt then did something quite bold: he gave the order to proceed with a news website without the ministry’s permission to do so. A formal approach would have taken months.

This meant everything about the news website had to be provisional, like some kind of skunkworks project; until the BBC could secure an agreement, bureaucrats in Whitehall could have pulled the plug at any moment.

It was a genuine concern. Lord Birt recalled how the BBC’s attempts to put the World Service online had been abruptly halted when the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, which sinks public cash into the international service, simply struck the line out of the budget.

“It wasn't a paralysing uncertainty. I assumed the government may fire a shot across our bows – but are they going to stand in the way of something that the BBC has a deep conviction about?" said the peer. "I'm sure I didn't have a deep worry. It was an irritation rather than a concern.”

It was now May 1997 and Eggington had no staff and no plan, but he had a deadline. He did hear some good news: the team leader at a major news rival was considering joining – and even better, may be able to bring some of his people with him.

How the tech team was put together, the software designed – and its mastermind found writing code at a dialup ISP

In late 1994, philosophy graduate Matthew Karas was finishing a master's degree at Cambridge in computer language processing. In Manchester in the 1980s Karas helped put pirate radio stations on air in Hulme and Moss Side, and he was a musician: his band Soil had earned handwritten fan mail from Morrissey. Unable to find a job in language processing, he found himself working shifts at a dialup ISP called Delphi for £7 an hour.

The internet provider had set up a consulting business, which was building Sky’s first websites. Delphi wanted to employ twenty staff to hand-code HTML and paste in content for the broadcaster's news, weather and sports websites. “Why not design a system to do it?” asked an astonished Karas, who then handed them what became one of the world’s first substantial web content management system (CMS). In the end, the software saved Sky having to employ 16 HTML grunts.

Rupert Murdoch's News International acquired Delphi outright, and cast the team into a joint venture called LineOne with BT and United News & Media. News Intl withdrew from the venture in 1999, and LineOne was acquired in 2001 by the Italian telco Tiscali. Today, it’s better known as TalkTalk, and is owned by The Carphone Warehouse.

Delphi would be a hub for London’s first generation of web coders, many of whom socialised on a mailing list called Haddock, including Matt Jones, Stef Magdelenski, Yoz Grahame, Tom Broxton and Karas’ friend from his philosophy studies, Stuart Tily. As the software boss, Karas had little time for the Haddock banter and in-jokes. What intrigued him more was building a better CMS.

Then came the call from Eggington.

Karas liked the can-do spirit of Smartt and Eggington, and the independence they had carved out in the vast BBC bureaucracy. They also discovered they had something else in common.

“We believed very strongly that the internet was for everyone,” Karas told The Reg. The BBC had launched a hobbyist ISP in 1994, the BBC Networking Club, for computer enthusiasts. “The BBC Networking Club, was fine for its time, but appealed to people who shop at Maplin.”

The technical brief of BBC News Online was daunting: the site would need to be constantly updated and offer stories in a variety of languages, taking feeds from the BBC’s World Service operation.

“I told Bob [Eggington] I thought it could be done within two years with 12 programmers. Bob said it had to be done in 16 weeks with 5 programmers,” said Karas. A date was set to launch in November 1997.

Matthew Karas

Karas handed in his notice at LineOne and took up his new job at the BBC on 3 June, 1997, returning to the ISP briefly over the summer to tempt across a dozen of the team: they were mostly software developers, but there were a few designers too.

Designer Matt Jones, who had already left Delphi, was one of the first to join the new operation, and was put in charge of prototyping how the site would look and behave.

Karas wasn't impressed by what he saw across the Atlantic. A CMS at ABC required journalists to construct sophisticated database queries to build articles, while another, at MSNBC, looked smart but wasn’t built for the intense workflow the BBC anticipated.

Karas also examined expensive packaged software options, including Vignette’s StoryServer, marketed by CNet. Vignette had rapidly acquired big-name publishing customers with big budgets, including the Guardian newspaper. But these packaged options still required a lot of integration work.

A risky architecture

If hiring chattering London techies was a gamble by Eggington, then the architecture Karas wanted – “a CMS done properly” – was also risky. And it was politically charged, too.

The BBC had a contract with ICL Fujitsu and every new project was obliged to use Fujitsu staff, and wherever possible, technology.

“I had knew what we wanted to do – from learning what worked and didn’t with my CMS at Sky," said Karas. "People were dazzled by the internet and interactivity, but underneath, it was a publishing system.”

Non-trivial technical issues, such as managing queues of articles awaiting publication, needed to be resolved. The system would need to juggle 60 in-house staff hammering it at once, publishing stories, with many more feeds coming in from other places. Karas devised a demanding specification that he knew ICL Fujitsu could not match. The News Online system needed to be able to publish an article from an editor’s desk within thirty seconds. The specification ensured that Fujitsu’s offering would fail: it couldn’t process the feeds, resolve the links, in the turnaround time required. Fujitsu withdrew.

Smartt was adamant the site wouldn't lazily publish stories direct from the wire feeds. Instead, he and Eggington wanted to tap into the vast amount of high-quality output generated by the BBC, particularly its World Service division, which broadcast to more than 40 countries. The BBC’s radio journalists used a VAX minicomputer with a system called BASYS (which DEC had acquired in 1992) that became Avid iNews – and also a Unix system called Edit. If the radio news scripts were in a computer somewhere, why couldn’t News Online use them? It wasn’t going to be easy.

Help was around, but Karas felt it wasn’t the right help. He wanted his team to focus on the overriding requirement of achieving rapid publishing, something that minicomputer sysadmins might not intuitively understand. This meant politely rejecting help from the BBC’s legendary technical expert Brandon Butterworth, who Karas had known from his pirate radio days: both had been in Manchester in the mid-1980s.

(Now the BBC's chief scientist, Butterworth tells the history of the broadcaster's web presence here.)

“Brandon was a visionary in a lot of ways: he foresaw the use of the internet for time-based media – such as radio and TV – before anyone else did. He knew the protocols were up to it, and what needed to be done,” said Karas.

“But the system really had to work for editorial – it was a publishing system. Brandon’s view was that of a system architect, a Unix guy.”

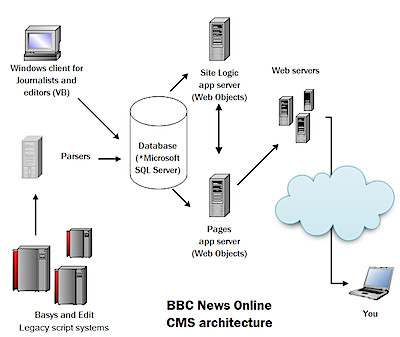

The architecture Karas devised in 1997 was a database-driven system although “the public were miles from a database”, he said: the website would publish mostly pre-built pages rather generate them entirely on the fly from the database every time a visitor requested an article.

The application servers were split into two groups: one set handled the content queues to produce pages for the public-facing web servers; the others ran the site logic. It was a loosely coupled architecture with several advantages: the interfaces between them were well designed, and it also meant one part of the system could be upgraded or, heaven forbid, break without significantly derailing the other parts.

The 1998 CMS architecture for BBC News Online

SQL Server was later replaced by an Oracle database, but the architecture remains (click to enlarge)

The design gave the BBC great flexibility, too: new output formats such as WAP, an Indian language edition, and a simple version for blind users, or Netscape and Microsoft push channels, could be added very quickly and easily.

At the centre of the design was the database, initially Microsoft’s SQL Server – which was fast and cheap – although this was later replaced by an Oracle product. The database accepted submissions from journalists, using a custom-built client, and the text scraped from legacy systems within the BBC empire.

Karas ensured the programmers were kept well away from the data store.

“Programmers don’t have a clue how databases work, particularly the security side,” he said. “I hired a database administrator just to keep them off the system.”

For the application engines, Karas made an unusual choice: WebObjects. Steve Jobs’ NeXT demonstrated the web programming framework in 1995; Apple acquired it along with Jobs in December the following year. At that point, WebObjects required a programmer to learn Objective-C, an esoteric programming language only really used at the time to write code for NeXT machines.

Karas felt this was not a challenge for a bright programmer, who should already understand object-oriented programming, and it was less confusing than C++. The Apple framework was ideal for web publishing, but the problem was that hardly anyone used it. Fortunately Karas was able to find two well-known reference customers who were using the software kit: NASA and IBM. Although neither used WebObjects in the demanding way Karas envisaged, it was enough to get him the green light to proceed.

“We were doing agile development before there was an agile. It was extensible, it was loosely coupled, and it was database-driven but not at the outward layer. The core of it is still there,” he said.

Tapping into existing internal BBC systems to scrape content was an inspired move, and a typically British piece of improvisation. Many radio production staff were located overseas, and there was no budget to fly them to London to teach them coding. The web news team wondered how to lift the journalists' work with minimal disruption.

The developers decided to add three simple instructions to the existing workflow: the correspondents or producer must add a headline to the radio script, they must spell correctly, and they must not leave in cueing information – such as advice for a continuity announcer on how to pronounce a name, or when to discard a given script.

“There were bad at headlines at first, and they would write a whole paragraph for them, but they got the hang of it,” said Karas. “But it worked. An editor sitting in Moscow who had never seen a web page was producing web pages.”

For the website design, the team took a leaf from The Register, according to Karas. Although El Reg was not yet a full-time operation – that came in April 1998 – it was was one of the first popular UK news sites. The Reg had a rolling front page with older stories scrolling off the bottom. The BBC designers devised an area in which major stories could be manually positioned, ideal for busy news days, and all other articles were simply listed in order of publication time and date.

Bugs, server wrangling, coding all night, none of these compared to the mindnumbing politics

At the time, internet projects at the BBC were handled by Aztec, a three-man external consultancy. The trio included Ian Stewart, who had invested in the ill-fated first attempt at a WiReD UK magazine that was partly owned by The Guardian. BBC tech projects had to defer to Aztec, bypassing their own tech gurus. Karas decided Aztec had to go, but it would be two years before the consultants' grip was eased. Eggington says he was obliged to use the consultants, but could ignore their advice.

Unusually, the small News Online team took decisions with editorial and technical staff chipping in advice rather than giving orders. Furious arguments were resolved without lasting animosity; nobody got religious about technology choices. But as the deadline day of November approached, the gang hit a snag.

Matt Jones’ design team had come up with a set of HTML layouts that followed best practice guidelines, but nobody was wedded to the styling, which made use of putty-like beiges and greys.

The BBC at the time was going through a corporate rebranding exercise, which involved commissioning a new logo from design agency Lambie Nairn. The BBC had used sloping letters for its logo, with few variations, since 1962. Lambie Nairn straightened the characters, and changed the font to Gill Sans, and the letters looked better on computer screens. The new logo had yet to be unveiled to the public, and only be made public on 4 October in 1997. Everyone was ordered to work with the WPP-owned branding agency. So rather reluctantly, the News Online team sent their templates to Lambie Nairn with the invitation to “reimagine” them.

Almost overnight, a junior working at the agency, who had no web layout experience, sent back a new set of designs. “Mike, Bob and I looked at them and thought these were so much better,” said Karas.

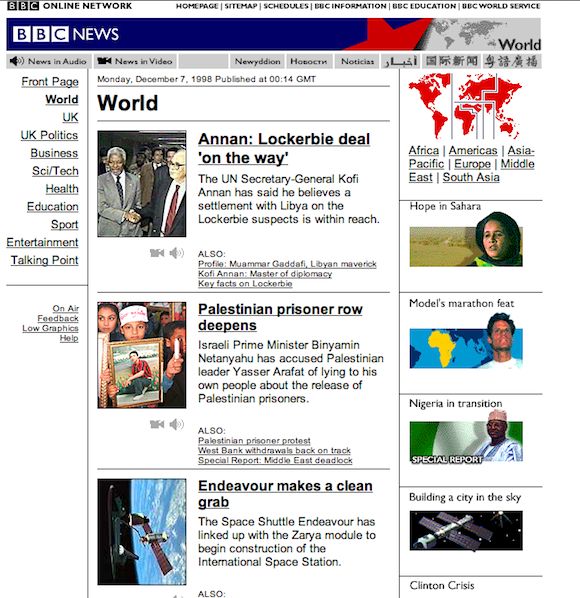

Without kicking up a fuss, Jones set to work rewriting the news website's HTML, even though this meant revising every template in the system. Jones would become creative director after the site's launch, giving News Online a clean, simple and consistent look, and some clever and subtle touches. Even today, the first News Online pages look clean and modern – one of the few websites from 1997 that hasn't dated – and look better than their contemporary versions.

There was one other problem. A senior BBC technical advisor, a Microsoft loyalist, had mandated that Beeb developers use Microsoft’s Replication Server: a now-forgotten piece of software that mirrored copies of folders across a LAN. For News Online, it was worse than useless, and it wouldn’t work across firewalls. Microsoft even jetted experts from Redmond to Blighty to tweak the product, but it wasn’t fit for the job the internet news team needed. The News Online gang lashed up a simple FTP script instead.

'We couldn’t poach them because Ceefax was a hugely popular service'

“Karas had an incredibly conceptually clear grasp of what’s going on, and what needed to be done from a user’s point of view,” said one Beeb executive. Meanwhile Smartt was recruiting reporters. Most of the BBC’s journalists were broadcasters – the only text reporters at the corporation worked for Ceefax.

“We couldn’t poach them because Ceefax was a hugely popular service that needed to be maintained – although one or two did apply to join news online and did so,” said Smartt. "Everyone was recruited through job adverts and many who joined were new to the BBC”.

Smartt ensured the site found its own voice. The team’s independence ensured it wasn’t running TV scripts. Working non-stop, the team made it. News Online went live on schedule.

“The speed of that original project meant that some of my team were working 16-hour days, 7 days a week. There were various burn-outs – three of my team had some long-term damage from the stress,” said Karas.

A veteran of the BBC bureaucracy, Bob Eggington had gambled that the longer the project took to launch, the more people would be able to delay it.

“The speed of execution was part of Bob's approach to minimise the risk of interference,” explained Karas.

The wisdom of this strategy was confirmed years later when the BBC iPlayer project racked up years of delays before eventually emerging in public. Originally conceived as a peer-to-peer distributed media system, iPlayer at one point had 400 inputs into the design process – almost every part of the BBC had a say in it – and that meant occupying a chair at a meeting. The project was only put back on course when Anthony Rose, now at Zeebox, stripped the core team back to 15 developers and focussed on shipping a Flash-based streaming iPlayer rather than a distributed behemoth. The endless design meetings were cancelled.

“Bob [Eggington] was a master at fending off skullduggery,” one of his staff recalled. It was a skill that he would need to draw on in the next two years.

The days and months after the successful launch – and attempts to wreck it

Despite early problems, News Online raced out of the blocks. At first it crashed several times a day – but it was up and running very rapidly.

The site started to double its readership every month. Smartt’s team quickly found a voice. The clean look, speedy operation and the breadth of material available reminded people of the scale and reach of the BBC’s journalism. It was definitely British – but the World Service feeds gave it a global feel.

The News Online home page a few days before launch ©Matt Jones

And the journalists were soon showing up their rivals.

“In my own field, science, we were doing it quicker and sharper,” said science correspondent David Whitehouse, who joined the team shortly after launch. “We completely destroyed everybody else.”

The citadel of BBC Newsgathering had initially ignored the newcomer. Before long, it was getting stories by looking at the BBC’s website. “Do you think when you get a good story, you could tip us off?” the head of newsgathering was overheard asking the news website team.

News Online was the first to cover the Ladbroke Grove train crash because, according to one BBC worker, “you could see Ladbroke Grove from the seventh floor where we were based. A puff of smoke went up. The website's managing editor, Dave Brewer, took a camera, took a picture, and we had it up online. We broke the story because he saw the smoke.”

Today there’s a mini-industry urging journalists to "learn to code", but Mike Smartt thought that was an unforgivable a distraction. “No coding was necessary – in fact, the use of HTML by writers became a sackable offence,” he recalled.

BBC News Online scooped the news website category at the BAFTAs in 1998 and for the next three years – until the category was abolished. Even so, another journalist speaking to The Reg said: “It took two to three years before the rest of the BBC realised that online would be just as important as TV.”

But the success brought enormous resentment. The biggest obstacle blocking the team wasn’t technical nor a commercial rival – but the BBC itself.

The Empire Strikes Back

Incredibly, despite the string of BAFTAs, the BBC’s biggest success story wasn’t appreciated.

The BBC’s Online operation, separate from the news website, was located in Threshold House, an overspill office on Shepherd’s Bush Green, where Ed Briffa, chief of Broadcast Online, and his new strategy assistant Azeem Azhar, an Oxford graduate in philosophy, politics and economics who had briefly been a Guardian technology correspondent, worked. The News Online team referred to this as “PowerPoint House”, an indication of the tensions between the two factions.

A snapshot from 1998

The runaway success of Eggington and Smartt’s new operation contrasted with the poorly focussed sprawl of the rest of the BBC’s internet operation. Broadcast Online operations had spent £30m on its sites. Meanwhile, the news website was run on a tight budget, cost a third of Briffa’s overall budget, and was eclipsing it in terms of traffic.

In early 1998, News Online noticed something strange. Server logs showed that all BBC websites had experienced an unusual spurt in visitor traffic. On some days, according to the logs, the most popular domain browsing the BBC was the BBC itself. What was happening? BBC Online had decided to include “non-human page impressions” in its numbers: around 65 to 80 per cent of the "hits" were actually coming from Microsoft and Netscape push channels. Just as sending a letter is no proof of its receipt, most of the subscribers never saw the pages.

The News Online team came under pressure to follow suit – and include its own substantial push numbers – but declined. The independent web traffic auditor ABC noticed the caper and refused to audit the BBC’s numbers.

Briffa departed in 1998, but there was no respite from his successor Mark Frost, an American who joined after a brief stint at AOL UK. Frost was convinced Will Wyatt, head of the BBC's broadcast TV and radio empire, could bring News Online to heel. But because the news website team had carved out its own reporting line – via Abramsky and Hall – at the start of the venture, that was never a realistic proposition.

“There were attempts to broker back room deals to take over News Online, sometimes someone would try to get control of the funding, sometimes asking for access to our database to repurpose news content elsewhere, and sometimes just leaving us to do good work and then taking credit for it," recalled one insider.

There are people who take credit for BBC News Online today who devoted their efforts to trying to sabotage it, one former insider noted wryly.

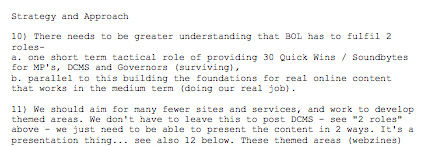

Quick wins and webzines.. a flashback to 1998

A memo to Briffa from his team in 1998 revealed a lack of focus, a craving for “quick wins” and the desire to create a technical bureaucracy.

Yet the BBC’s top brass could see what worked and what didn’t – and News Online worked. Before he officially took office, Greg Dyke – the incoming director general and Lord Birt’s successor – visited Eggington and Smartt, and was impressed. Dyke was actually gauging who was most competent in Online to launch a sport website – which would have been a huge boost in traffic for whichever team won. Dyke was impressed enough to give the News Online team the job.

BBC Sport landed the web news gang another another huge success. Jones gave the sports pages a distinctive yellow background – much like evening newspapers printing Saturday scores on pink paper. The BBC’s first attempt to put the football results online saw them published at midday on a Sunday. It has come a long way since. The success of the sport site ended any realistic prospect of Fujitsu reviving Beeb.com, or the Broadcast team ever finding a hit. The Broadcast Online rivals began to peel away into the private sector – or tried to join News Online.

Karas recalled spending hours discussing URLs with Tom Loosemore, who had joined Frost’s team and was attempting to build a site for the 1998 World Cup. Loosemore was one of several who wanted to switch to News Online. No one could find a job for him in the team. He went on to head a large team devising “BBC 2.0”, which was cancelled, and now works at a vastly expanded Cabinet Office devising "GOV 2.0" – a project to streamline public-sector websites. After months of deliberation, the GOV 2.0 recently standardised on a new font for Whitehall sites, called Transport.

The sports page: the yellow 'un

Briffa’s successor Mark Frost, introduced to the BBC by Azhar, lasted a year. BBC Online staff drifted away to cast their lot in the first dot.com bubble. Azhar himself would start eSouk, a short-lived incubator.

“I warned the news website team from the outset that their startup wouldn’t last. As the News Online site became more vital to the BBC, it was inevitable it would be brought back under central control,” recalled one executive.

Having seen off the worst of the threats, and with News Online now a core part of the BBC, Eggington moved on in 2000. Karas joined a spinoff of Mike Lynch’s Autonomy. Mike Smartt led the editorial team until 2004, and was made an OBE that year.

What made it succeed, then?

“Apart from the well-matched team, the simple truth is that we had a clear and valuable mission, while something like the EastEnders discussion forum didn’t," said one former executive. "People came to the BBC website for news and sports – which is news – or for programme information. Now they come to watch a program. Everything else, the vanity pages, is cruft.

“Bob [Eggington] put up a wall around the team stopping harmful external interference. We would offer to help other departments but it had to be on our terms. We ended up helping World Service quite a lot."

The site had a clear focus, and it focussed relentlessly on what the licence-fee payer really valued from a BBC site: reliable news trickling in over a slow dialup link.

“In those days nobody really knew what they were doing – it wasn’t unusual for half the budget on a project to be wasted, or 80 per cent. We had a very clear idea of what we needed to do,” Eggington said.

Karas agreed that it’s the lack of focus that explains why generously funded web publishing projects fail: they hire talented people, but don’t tell them what is needed.

“It's as though people think that the ingredients for a good web operation is hiring well-known website builders, rather than having a vision for some useful, informative or entertaining content," he said.

That’s a little bit like starting a newspaper by hiring some printers and telling them to print a newspaper. When it doesn't work out, it's not the printers' fault".

All three executives were driven to make it succeed. They also knew how to defend the fledgling operation from the BBC bureaucracy. And there was a huge element of trust down the chain of command. Lord Birt trusted Abramsky, and Abramsky trusted Eggington and Smartt to deliver, and fought their corner for them in the boardroom.

A huge degree of trust was placed on the techies to build the world’s most demanding news content management system – which paid off. And this trust was also enjoyed by correspondents, who were proud of their role in the system and were highly motivated. “They gave creative people what they need, a bit of space,” recalled one reporter.

And the quality of the staff was excellent. “BBC managers aren’t always very good – but Bob Eggington and Mike Smartt were exceptionally good managers,” said Whitehouse. Eggington himself says it was simpler than that:

“We wanted the best thing from a user’s point of view.” ®