Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2012/11/23/why_os2_failed_part_one/

IBM insider: How I caught my wife while bug-hunting on OS/2

No wonder that chkdsk flaw was never fixed

Posted in OSes, 23rd November 2012 09:39 GMT

Part one The unholy alliance of IBM and Microsoft unleashed OS/2 25 years ago with a mission to replace Windows, Unix and DOS. Back then, I was a foot-soldier in that war: a contract bug hunter at Big Blue. Here’s how I remember it.

By cruel fate, an even crueller editor has decreed that a quarter of a century later I must write an article on whether you should still bet your career on Microsoft. And I am struck by the way that those who’ve not read history have condemned themselves to repeat it.

'In some ways my work has been to make life hard for Microsoft'

In the late 1980s, most PCs still ran one program at a time, although some were infested with Terminate and Stay Resident hacks that fought among themselves. Graphical user interfaces appeared on desktops - but Windows apps tended to screw with one another big time: even if you simply turned on a Windows PC and didn’t do anything further, there was a good chance it would crash all by itself.

Then preemptive multitasking operating systems that could protect apps from each other became viable on Intel chips, thanks to new microprocessor features and improved performance. The idea of a super-DOS arose and was quickly seen as having potential to deliver something more special, for which they needed me...

IBM was pathologically secretive. My job interview consisted largely of the manager asking “so Dominic, tell me about yourself” with no indication of what they’d want me to do. I’d been involved in Microsoft’s Intel x86 Unix, though not in any useful way, so I replied: “In some ways my work has been to make life hard for Microsoft.” The recruitment pimp had told me that IBM bosses usually “took their time” to make decisions, but this time the offer was on my answering machine before I got home.

So I turned up and was paid to do no work. I was in IBM UK’s lab in Hursley, near Winchester, but no one seemed to want me to actually do anything. I had signed a contract with a non-disclosure clause (which has now expired I should made clear), but apparently that wasn’t good enough. I offered to sign another one but no one knew where to get it.

Eventually this was resolved, and I was assigned a PC but not even given an email account to use because I was a contractor, an untermensch. The only way for me to get email was to pretend that I was the contractor who used to sit at my desk and so I used his ID for the next three years.

(As another example of my lowliness within the company, someone in a HR department somewhere somehow got it into their head that I was female. I’m not a pretty man, trust me on this, but I'm also not a Dominique. Moves were afoot to end my contract before I could claim maternity benefits - not even the sexism was competent.)

Dozens of man years were sucked up by penny-pinching arguments over expenses when programmers on the critical path were sent to the US to get OS/2 finished while housed in digs rejected by students. IBM management, of course, stayed in the same sort of accommodation that all Microsofties were put in regardless of level.

We’ll always have a trip to Hawaii, er, ish

Microsoft developers on the OS/2 team were promised a week in Hawaii if they got the thing finished and, of course, had share options. IBM tried to compete with a trip to the Azores, which wasn’t quite as good. It was irrelevant anyway because Big Blue's HR vetoed our prize on the grounds that IBM rules prohibited that many IBMers being on the same aeroplane.

Instead IBM HR came up with a plan that summed up the department's view of tech staff: a dinner dance. In Southsea. For our non-British readers this is not a glamorous location.

As a scumbag contractor I wasn’t invited, but since I was dating one of the seven women on the project, I went anyway and was impressed by the way IBM had tried so very hard to make the inside of a municipal leisure centre look like Hawaii. This is so crap that the integrity checks I’ve installed to watch myself for incipient senility keep flagging it as a false memory.

The only way I can force myself to believe the idea that the richest corporation on the planet behaved that way is that the girl who took me is now a reassuringly expensive lawyer who was kind enough to marry me and so we have photographic evidence.

(I wish to make it clear that I’m not saying IBM had the worst HR of any firm in the world, merely that my 28 years in technology and banking have never exposed a worse one to me.)

In that context it is a mystery as to how they hired people who were among the smartest and most pleasant IT pros I’ve ever worked with. Even the guy that both Microsoft and IBM developers referred to as the worst programmer in the world was easy to get on with. Shame that a few years later he died fighting for the Taliban.

Anyway, back to the technology. OS/2 was getting a hugely improved graphical user interface called Presentation Manager, an industrial-grade graphics library based upon IBM's successful GDDM, and plans were underway to include a proper database and host connectivity in the operating system itself.

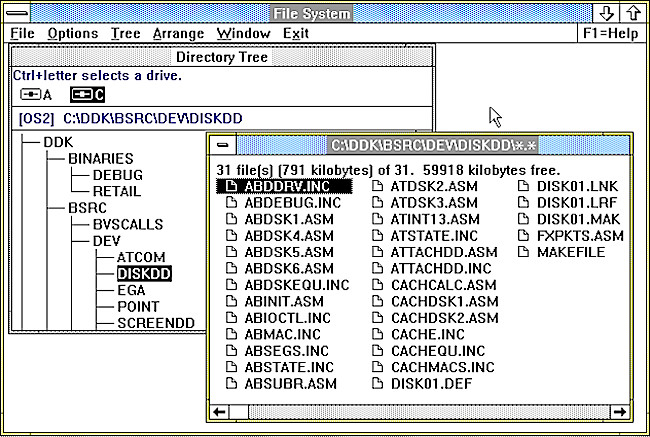

Something familiar about all this: OS/2's desktop. Credit: OS/2 Museum

OS/2 1.0 went out as a text-only super-DOS. What we saw as “real OS/2”, aka version 1.1, was released a year later and contained the super-doopa graphics support. We even had the shiny new VGA standard to drive it.

There was also a graphics markup language that allowed you to design sets of windows and attach dynamic code to the pages that could be downloaded from a shared directory. We thought that was cool and in the early 1990s we kept wondering if it could be made to do something special.

Testing was a concept Microsoft struggled with

Testing OS/2 was a concept Microsoft struggled with at the time. More than once I had to deal with Redmond code that was reported to have passed and failed various quality assurance tests with complex behaviours, yet for some reason that code consisted solely of a RETF instruction, which (in theory) simply ends a subroutine call.

Their code reviews were a joke. Their developers put source code comments of the form “Skip over random IBM NLS shit” in the support for national languages, and the comment “if window count is zero return false” was next to a line that always returned zero. Microsoft flatly refused to fix this one saying that it conformed to Redmond's coding standards, a copy of which we never managed to acquire if it actually existed.

We, on the other hand, were regarded as hopelessly bureaucratic. After Microsoft lost the source code for the actual build of OS/2 we shipped, I reported a bug triggered when you double-clicked on Chkdsk twice: the program would fire up twice and both would try to fix the disk at the same time, causing corruption. I noted that this “may not be consistent with the user's goals as he sees them at this time”. This was labelled a user error, and some guy called Ballmer questioned why I had this “obsession” with perfect code.

IBM had sheets of stats on productivity and financials, the software development equivalent of AIDS. For no good reason, IBM thought software quality correlated to things like the abundance of newline characters in the source code.

So Big Blue extended its bizarre measure of productivity - the number of KLOCs, or 1,000 lines of code - to such an extent that the source code editors we used came ready with macros to bulk up your code; for example, it would extend C comments over multiple lines to make your code pass insanely dumb metrics. Suddenly, everything looked good.

Because we were starting from a largely clean base, we could do things right with OS/2. Even with the benefit of more experience and hindsight I think nearly all of the engineering decisions were the right ones and the implementation was pretty sound by the standards of the time.

IBM's Personal System/2 PC was announced at the same time as OS/2, and the computer was supposed to primarily run our operating system - but the first shipments of the hardware ended up using PC-DOS.

Most OS/2 developers at IBM and Microsoft not only didn’t use PS/2s, we weren’t even aware of their existence until too late. The parallel with Windows Surface tablets is quite striking here - a spurious marketing connection between hardware and software. Whereas PS/2s struggled to run OS/2 properly, the Surface can’t run a decent version of MS Office at all and is incompatible with Windows on purpose.

OS/2 was elegant

As OS/2 quickly evolved from an extended DOS, shared libraries and threading support were added to the mix as was the idea that the operating system's software interface - the API - should be carefully designed rather than allowed to become a mess of randomly named functions.

The API was coherent enough that you could guess the order and type of parameters because they followed a pattern without reading the documentation.

There were real arguments over the API design, though, and it was not astonishing to see a six-page change request for the name of one API call. This doesn’t sound too bad until I share that the call was eventually named WinBeep. There were even existential arguments over whether beeping should be allowed.

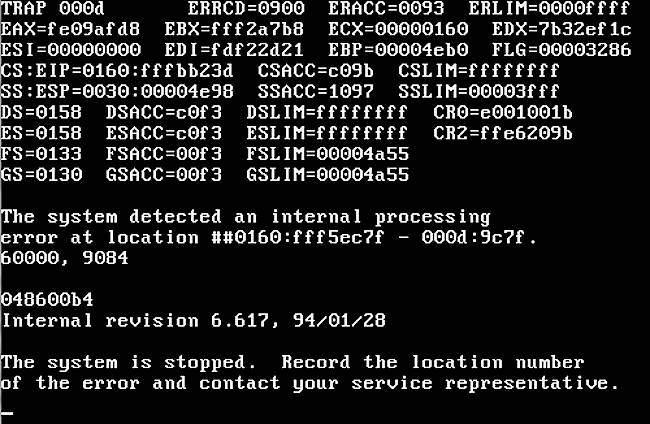

Still, my favourite was the SheIndicatePossibleDeath whereby the Shell (She) would signal that that the system was not well and that steps should be taken to recover or gracefully restart. The Microsoft devs thought this was hilarious and instead felt that the Trap D black screen of death was all a user needed to see in such cases.

Oh, I see! Trap code D, it's so obvious what's wrong

They, of course, eventually demonstrated their superior skills by upgrading Windows NT to the blue screen of death and giving secretaries, accountants and other office users such vital information as the various memory addresses involved in the screwup so that they can patch a dodgy device driver.

So, were there any API code examples?

No, you fool. The OS/2 API documentation was programming-language neutral. Some examples of actual code was in the development kit, and it was of high quality, but it was perhaps one per cent of what needed to have been written.

Documentation was hard to maintain due to the sheer speed at which changes were made to the API. One of the times I made myself unpopular involved revealing a simple mathematical model that showed the rate of change of the system was so high that our developers could not keep up and the testers could not even write the tests for it.

This meant the project would either be late or never ever reach completion and there was no third possibility: shipping it on time. I wasn’t the only person pointing this out, but no senior IBM manager wanted to be the first to say with authority that the product would be late. I can’t believe you haven’t seen that on your own projects.

I write this article with hindsight, but be clear that I was near the bottom of the food chain and most of the decisions seemed reasonable enough to me.

In spite of this, OS/2 was easier to program than anything else you could find. We knew this for a fact and buried somewhere in IBM are the videos to prove it. IBM hired in skilled programmers from every platform and asked them to carry out various programming tasks in the usability lab and they took longer than they should have.

The problem was that the developers kept on asking “how do I do X” where X was some hack or workaround you didn’t need to do in OS/2. Mac and Windows developers actually seemed quite angry that so many of their favourite kludges were not needed.

After years of manuals that consisted of insider jokes and interesting puzzles, the Unix devs admired our documentation. The DOS programmers thought Christmas had come and wanted to come and work with us.

I tried and miserably failed to get those videos put out as part of the advertising for OS/2 which was, well, really quite like the advertising for Windows 8. You could tell a lot of money was spent, but it left no real reason in your mind to actually do anything about it. In any case like Microsoft now, IBM wanted to talk to “real people”, not those who understood computers and made the IT decisions for businesses.

Documentation is another part of the whole saga where I share in the guilt of failure. This was before I took up writing, and I could have helped the documentation team more but it was a bit dull.

I was on the inside track of the OS with which MS and IBM both wanted to rule the world; I expected to make real money from the project, so the fewer plebs who understood OS/2 programming, the better for me and IBM.

Or so we thought - look out for part two. ®