Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2012/11/14/the_secret_history_of_liberator_the_first_british_laptop_part_two/

Liberator: the untold story of the first British laptop part 2

Out to launch

Posted in Personal Tech, 14th November 2012 12:00 GMT

Archaeologic It is 1984 and Bernard Terry, a civil servant, has devised a 'portable text processor' to make his fellow civil servants more productive in the office and out. Electronics giant Thorn EMI has agreed to manufacturer the machine, which will eventually be called the Liberator and become Britain's first laptop computer. Thorn has taken on the R&D team from the collapsed Dragon Data to design the Liberator. For all the details, check out Part One of the Liberator story.

Now read on...

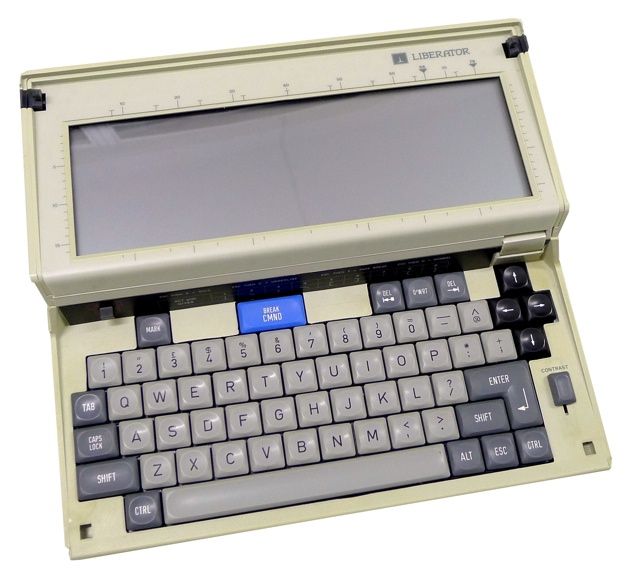

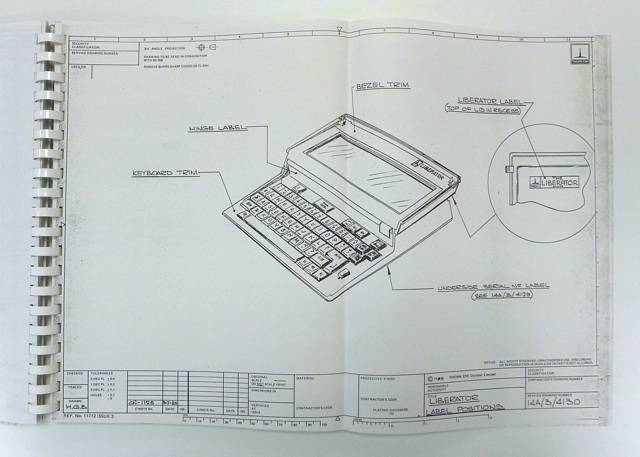

The Thorn EMI Liberator

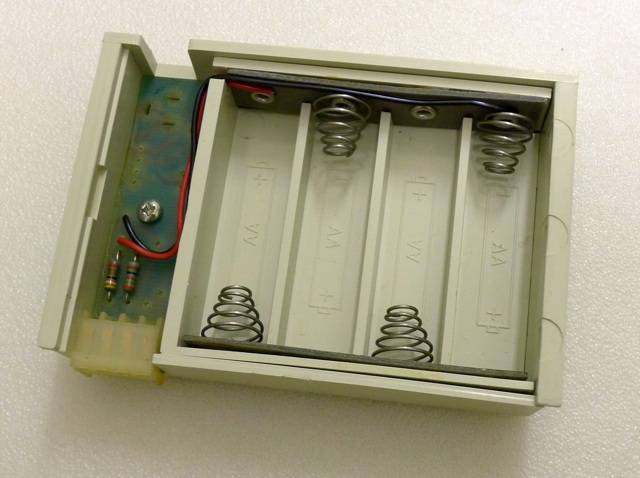

Another important hardware design choice to be made was the new machine's mobile power source. A battery, of course - but what type of battery? Today, designers would unthinkingly adopt a rechargeable, but that wasn't such an obvious move back then, Liberator hardware engineer Jan Wojna remembers. He did design a NiCad battery pack and it was offered as an accessory for the Liberator, but the prime mobile power pack would be a box - to make it interchangeable with the rechargeable unit - into which the user could slot four AA cells.

"Using rechargeables created all sorts of design problems," says Wojna, "because of the very wide variation in output voltage that you'd get from a batter pack when it was fully charged and the curve that you got as it discharged, requiring you to initially reduce the voltage and when it dropped below a certain voltage invert it back up again to keep it at a steady 5V. That was actually one of the main challenges."

The AA pack - model number LABH1040 - offered better runtime than the LRBP1030 NiCad battery did. It could keep the portable operational for 16 hours; the rechargeable unit would give you just 12 hours’ work time.

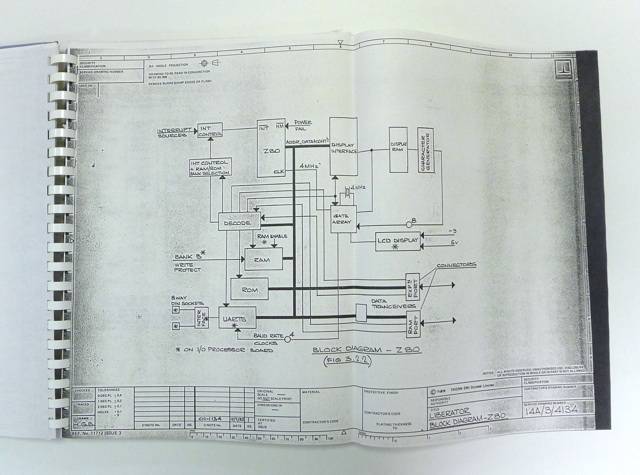

From the Technical Manual: from the motherboard schematic...

This was early, innovative work in the field of mobile device power management. Plenty of effort went in to getting it right, Wojna recalls. "No matter how good everything else might have been, if you couldn't get a decent battery life out of your pack, you didn't have a solution."

Another challenge: space. One of the key design decisions, says Wojna, was to integrate as much of the electronics as possible into a single integrated circuit - not easy given the "quite primitive" tools available to enable such integration. With this custom silicon housing all the hardware controllers - keyboard, screen, I/O etc - Wojna didn’t have to fit much else onto the motherboard other than the processor and the memory.

It’s a sign of the difficulty in designing a complex IC in those days that this component was one of the last Liberator parts to be completed. It was built out of a California Micro Devices - now On Semiconductor - Field-Programbale Gate Array (FPGA). Wojna says four sample chips finally arrived from the foundry right before Christmas 1984. He and design team director Derek Williams couldn't wait to try them and sneaked away from families and into the office on Boxing Day to test the chips. The first was fitted into the prototype. The Liberator failed to boot. Spirits fell. Had the team got the design wrong? If so, could it be fixed and new silicon produced in time to meet the tight six-month development deadline Williams had encouraged Thorn EMI management to set?

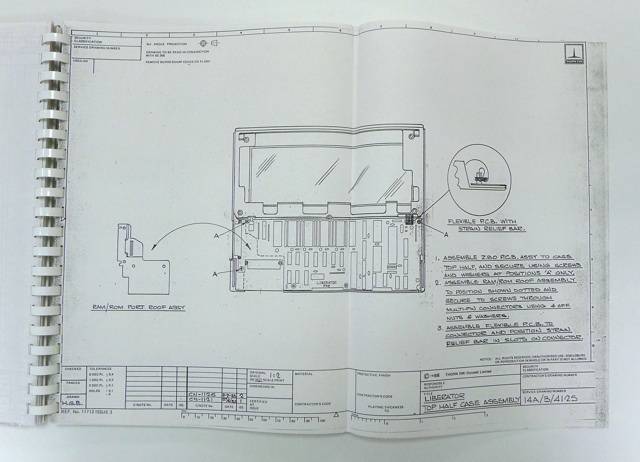

...to the top of the clamshell...

There was much relief, then, when the second chip was put in in place of the first, and the machine started up and worked as planned. "It was a duff chip - it did nothing. All the other three worked perfectly."

Another innovation: using piggy-back sockets for the Liberator's S-Ram chips, a solution leapt upon as the only way to get all the necessary chips onto a board that had to be sufficiently small to fit into an A4-footprint case. The problem, however, was that no one was selling the sockets in the UK, says Williams, so the team bought direct from a US supplier. That caused some friction, he recalls, with Thorn EMI's huge, centralised, highly bureaucratic and jealous of its role purchasing department. Allow small, fast-moving operations to do their own buying? Well, that's it's not how it's done here.

"We had to break every rule in their book to get this thing developed on time," says Williams.

Other aspects of the Liberator's hardware specification were defined by the needs of the operating system. So while Wojna was hammering out the electronics, software engineers Duncan Smeed and John Linney, aided by John Constant from Digital Research, tuned CP/M and its then brand-new menuing system for the new machine. Linney also wrote the text-editing software, which would later be released as Wordcom, coding the application in the then relatively little used C language rather than assembler, again in a bid to save time at the cost of a small but acceptable memory footprint overhead.

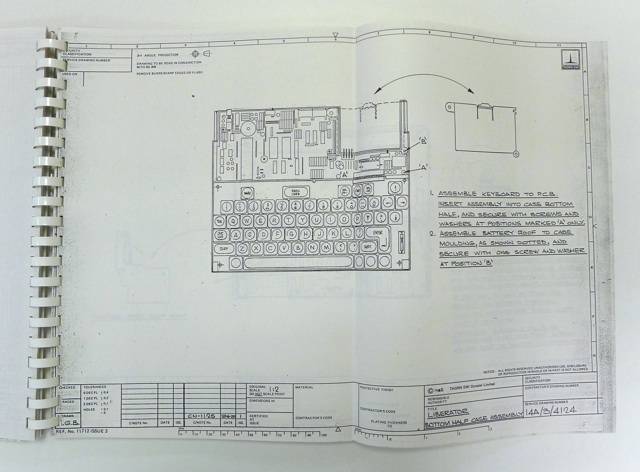

...and the bottom half...

During the development process, the team were in almost constant contact with Bernard Terry who became, as Linney now recalls, "a focus group of one", overseeing the work the team were doing on the user interface, the physical interface and the word processing software, and steering them back on course when they move the product beyond what he believed civil servants would be able to understand and use.

"They kept coming back to me on specifications, and then they produced a prototype which I trialled and then modified," Terry recalls now. "They used me as a free consultant! They would say, 'we want to do this', and I would say, 'we don't want that, it's too complicated'."

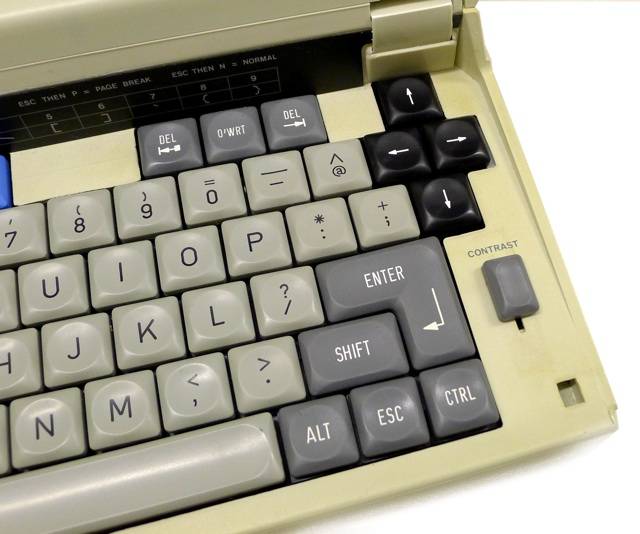

It was Terry, for instance, who rejected the calculator-style keyboard originally held to be necessary to keep the machine's thickness down. No, he said, the Liberator must have a keyboard with large, full-travel keys. Interestingly, a memo Terry wrote to Andy Powell, Thorn EMI's business development manager, in August 1985 reveals that "during the initial stages of the UK kneetop development, a fair amount of thought was given by Derek [Williams] and I to the use of an alternative keyboard to the typing Qwerty style, as the unit was to be aimed at non-typing staff" and because "the CCTA have always shown an interest in a move towards more efficient and ergonic [sic] keyboards, including the Dvorak and the Maltron".

...then put the two parts together

Ultimately, though, the scheme didn't come to fruition: the Liberator would ship with a Qwerty keyboard. "We were already breaking enough conventions with the Liberator," wrote Terry after development was complete, "and settled for the de facto standard."

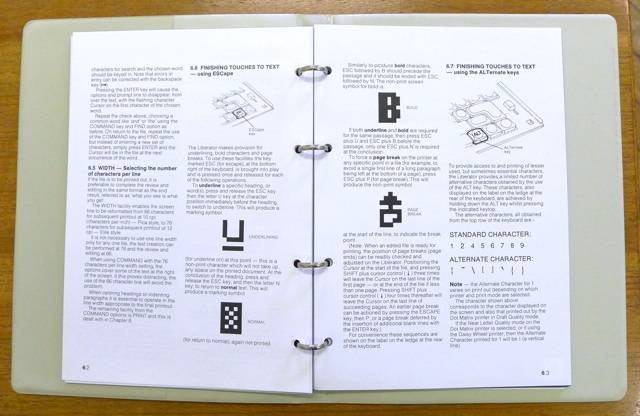

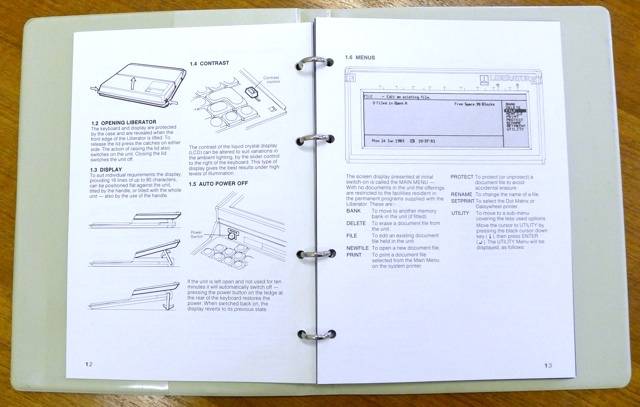

The Liberator lives... almost

Both Terry and Williams insisted on a large display - notable at a time when past mobile computers, especially those he had evaluated in a bid to find a suitable machine for his Civil Service colleagues, had either tiny screens or wide, but shallow displays. The need to include the big screen - a Toshiba-made 80-character by 16-line job with a pixel resolution of 480 x 128, supplied without a display controller so Jan Wojna had to design one and build it into the FPGA; comparable products had 40-character by eight-line screens - almost certainly inspired the Liberator's clamshell design.

Derek Williams handled with the Liberator’s industrial design. The six-month design and build timeframe made gearing up steel tools for the machine’s injection-moulded case impossible to achieve, so Williams sought out firms who specialised in aluminium tooling and had experience in injection moulding. “Steel tooling would have take three to four months to prepare,” he says, “and that would not have worked for us. We needed to be able to develop the mouldings very, very quickly.”

The 'CMND' key was crucial...

Williams approached the Production Engineering Research Association - now simply Pera - in Melton Mowbray, and Pera put him in touch with a consultant to work on the Liberator. “But they like steady, stable projects, and they weren’t used to pressure and constant revisions, and the guy working on the design and the tooling, he couldn’t handle the stress.” Williams began to search again, and found a Gloucester-based designer called Miles Bozeat. “He had experience in aluminium tooling, he was a very innovative designer. He took the project over from Pera.”

Bozeat came up with various designs, not only the angular look that was ultimately adopted for the Liberator but also a more rounded case which, Williams recalls, was the one favoured by Bernard Terry. But it was veto’d by the Thorn EMI marketing department, which favoured the “more contemporary” look that the machine eventually shipped with.

The Liberator, then, was a surprisingly thin and light machine, cased in cream plastic, with hinge half way along the top surface. Release the black catches on the left and right sides, and the forward part of the upper case springs up to reveal the 62-key keyboard, a slider control to adjust the screen's contrast, and the machine's monochrome LCD screen. Displayed around the panel: character- and line-count rulers, a nod toward the typewriter's formatting aids.

Knee-friendly underneath?

The rear of the Liberator, which is where the majority of its ports were located, was protected by a plastic strip that could be pulled away from the back of the machine to form a carry handle. Fold the handle down and it became the laptop's stand. Rotate it the other way, up and over the top of the machine, and it became a support for the display, which would otherwise fold to lie back flat onto the top of the portable.

The screen had no fancy hinge, simply a thin - but durable, if surviving Liberators are anything to go by - plastic strip connecting the separate display housing to the body of the laptop, and containing the screen's signal ribbon cable and power feed. Pulling the handle away from the back of the machine exposed the Liberator's removable 9V battery pack, its two 8-pin, 9600 Baud Din-type serial ports, and a parallel Ram expansion port. There was a second, general-purpose parallel expansion port on the Liberator's left-hand side.

The Din ports were based on a specification called S5/8 - for 'Serial five Volt, eight-pin'. Its use had been proposed by the Public Service Working Party (PSWP), under the recommendation of Technical Consultant Andrew Hardie and others. The PSWP had found RS232 to have become a "plethora of incompatible sub-sets" of the standard, while an alternative interface, the Centronics specification, was impractical for mobile use because of its "expensive and even larger multiway connectors". So the PSWP devised S5/8, which would, the organisation believed, provide a simple, low-cost and low-power alternative ideal for mobile computers. It pitched S5/8 to the British Standards Institute (BSI) during 1984, and the technology was subsequently added to the Liberator specification.

...but the Contrast control never quite overcame the LCD's limitations

The PSWP's motives may have been sound, but it proved a mistake for the Liberator. As reviewer Nick Walker noted in his evaluation of the Thorn EMI Machine for the September 1985 issue of Personal Computer World magazine: "It's doubtful this new standard will be adopted by printer manufacturers... Even Thorn EMI's own printers, especially selected for the Liberator, are Centronics machines with the necessary conversion box."

Specifications later suggested for next-generation Liberators would feature Centronics port.

The first Liberator's on-board memory was segmented into two banks, A and B, containing 40KB and 24KB, respectively - 64KB in total. There was a further 8KB of Ram on board for system use, but only the amount of user-accessible memory was stated in surprisingly honest promotional material. Flip a slider switch on the back, and bank B would not only kept powered by its own battery, but write protected like a diskette. Both banks were also fed from the main battery even when the Liberator was turned off, allowing their content to be retained - an amazing innovation in an era when most computers used floppy disks for non-volatile storage, hard drives were simply too big and too power hungry for a portable, and Flash solid-state storage was the stuff of dreams.

Even if the main battery ran flat or was removed, memory bank B's contents would be preserved by a built-in button cell that provided 50 to 500 hours' data protection, Thorn EMI claimed at the time.

The two ports are the Din-based S5/8s, the would-be UK standard

According to the Liberator manual - preserved, along with a machine and many of its peripherals by the Science Museum - the machine's "memory is allocated in 'blocks' of about one thousand characters". Two blocks were assigned to the word processor's paste buffer. Linney recalls that memory was implemented in Static Ram because it consumed less power - energy wasn't expended regularly refreshing each memory cell's state.

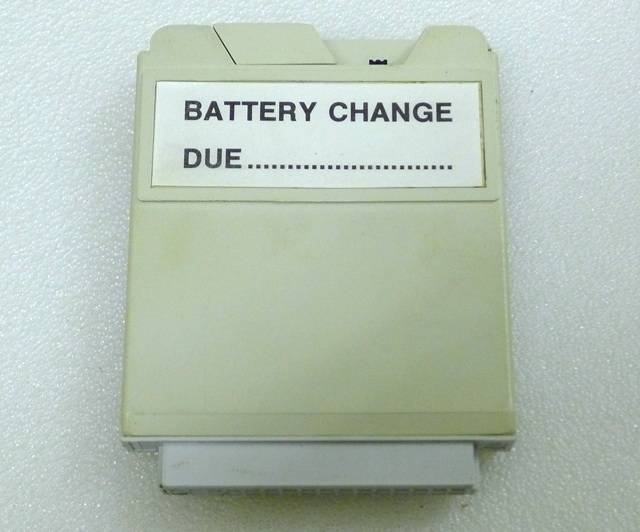

Not every machine came with Bank B. Two models were put into production: the 40KB LPTP1001 and the 64KB LPTP1002. The former only had Bank A fitted, the latter Banks A and B. Both banks were separate, as was Bank C, added to either machine plugging the LRAM1060 24KB Ram pack into the Liberator's expansion port. It too could be write-protected and kept powered with its own on-board battery, allowing it to be used to swap files between machines.

The Liberator today

Viewing the Liberator 27 years on in the Science Museum's collection, I was struck by just how portable Thorn EMI's team of engineers had made the machine. The spec sheet quotes a battery-less weight of 1.7kg. Add a further 200g for the NiCad power pack and the total is not that much greater than a typical modern 13in laptop. Long-time mobile computing fans will have had to lug much heftier notebook computers around in the years since then.

With its 295 x 252mm footprint, the Liberator doesn't take up much more desk - or knee - space than an A4 sheet of paper. At 35mm thick, it's not exactly chunky, either.

One of the two Liberator battery packs...

Similar thoughts occurred to PCW reviewer Nick Walker. “On removing the Liberator from its box, the first thing that strikes you is how thin the unit is... it is no more than 1.5in thick,” he said, adding that the Liberator had “probably the thinnest full-stroke keyboard I've seen. Even so, the keyboard is nice to use, with sculptured keys and a good, positive feel...

“The screen is... surprisingly large for a machine of the Liberator's price, and as such is capable of holding a decent amount of text on a single screen.”

True, but other reviewers had problems with the display. Not its size, but the nature of LCD technology in the mid-1980s. Punch's Michael Bywater was typical: "A lot of people hate LCD screen, I know. I'm not that keen myself, since they require direct lighting and direct lighting means that you get some glare off the screen glass, and if you move the lighting to avoid the glare, you can't see the screen."

...and, yes, it could run happily for hours on four AA batteries

Michael Becket in the Daily Telegraph said seriously: "The screen is as good as any liquid crystal display. Opinions vary on the clarity of such things, but a reflective surface detracts from readability."

The Financial Times played it for laughs: "She opens the lid to reveal a flat, grey plastic screen. 'Beep,' it says in welcome. She types a few words but find its difficult to see them. She turns the machine this way, swivels it that way. All she sees on the screen is her own reflection, so she uses it to adjust her make-up. At £650 (excluding VAT), the Liberator makes an expensive mirror."

Carried using the handle - though the Liberator was also supplied with a branded, leather-look shoulder case, possibly the world's first dedicated laptop bag - I found it to be a remarkably easy machine to move around. The manufacturing quality is typically early 1980s British, but don't forget this machine was made in an era before today's highly computerised, ultra-precise production techniques evolved.

Flip the switch on the battery-backed Ram pack to keep the contents safe from accidental erasure

That said, even contemporary reviewers were concerned about build quality. “Generally, the standard of workmanship on the review model was not equal to that on similar Japanese machines,” wrote Practical Computing’s Glyn Moody. “For example, the various sections of the moulding at the back are not totally flush, and the spring door on the Ram port is wonky. Thorn EMI says that the machines which will be sold to the public have better tolerances and overall finish.”

Maybe the manufacturer did say that, but judging from the machine I saw - a unit sold to a civil servant, not an early review sample - the Liberators provided for sale were no better.

I wasn’t permitted to power up Science Museum’s Liberator, but looking at the screen and trying the keyboard, I could see Bernard Terry’s vision of a portable device for getting down ideas and drafting documents was fully realised. Judging from the manual, and from the memories of users, it’s clear the development team had produced text manipulation tools writers would find themselves at home with today.

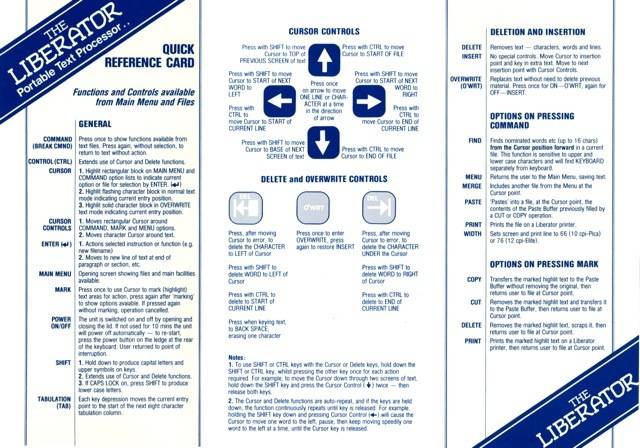

Fold-up pocket guide: all you need to know to operate the Liberator

With the development work almost complete, Thorn EMI Information Technology’s marketing team, led by Ian Milne, began drumming up interest in the press. In late January 1985, Milne told journalists that the company was about to launch a portable machine codenamed ‘Mat’, for Management Aid Tool. Milne promised the system would launch before March.

It's not clear who coined the name 'Liberator' - Milne or one of his marketing team, says Derek Williams; it was a marketing department decision. Certainly by mid-February 1985, 'Mat' was out, Liberator was in.

Ready to launch... almost

The Liberator design team's first working prototypes were little more than circuit boards with keyboards and screens attached. The CCTA's deal with Thorn EMI called for an initial delivery of 40 complete units. These were hand-assembled by the team during the first months of 1985 when a strike at the Treorchy, Wales plant ensured that the original plan of getting workers there to build them had to be abandoned.

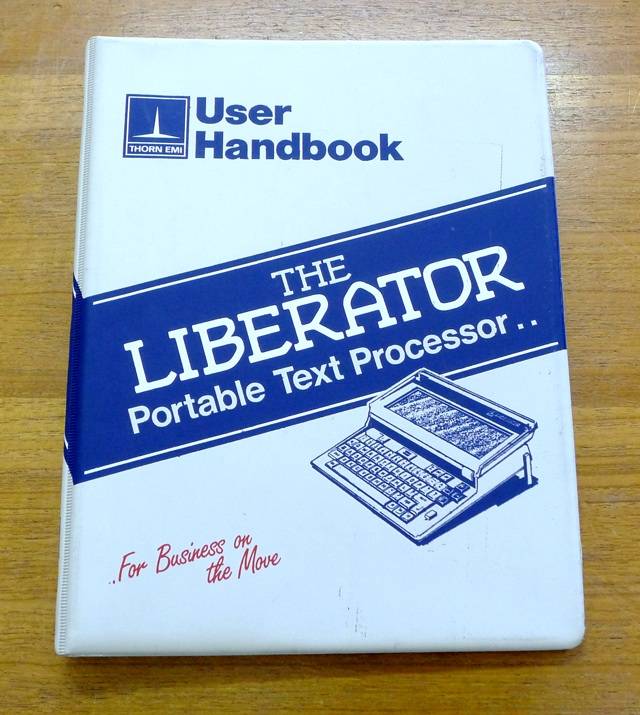

Manual override: the Liberator was not promoted as a computer

“We all did whatever we had to do to make the thing work, and that meant forget about demarcation," says Williams. "There were obvious skill sets and that dictated who was going to do what, but at the end of the day, it was a joint effort.” So there was never any question of anyone not mucking in to get the units built. They all grabbed soldering irons and screwdrivers and set to work.

"We loaded up the back of my car, and I drove down to London and delivered the units to Bernard," remembers Williams. "Then I went to Sunbury-on-Thames [site of Thorn EMI's HQ] and showed them the receipt for the goods. They were totally gobsmacked. No one had delivered a project of that complextity on time and on budget before."

Bernard Terry handed six of the first prototypes to civil servants for pre-release testing. "I selected about six people who would then trial them and come back with feedback. For instance, one of the things the I underestimated was the file size that people required - it was bigger than I thought it should be. Now we had a limit on the file size, and we had to change it. And people would come back and say, 'It would be good if it did this, or it would be nice if you could add that', and we did keep on modifying and hopefully improving it.

RTFM... but you never really needed to

"The main faults we found were manufacturing faults rather than system faults. There was nothing wrong with the software, there was nothing wrong with the hardware - it was how they were putting it together in South Wales," he told me.

Thorn EMI previewed the Liberator to 70 senior Civil Servants on 21 February 1985 at an event held in Riverwalk House, the CCTA's HQ. Bernard Terry discussed the motivation for the project and the thinking behind it, and demo'd the Liberator to attendees. Derek Williams talked about Thorn EMI's commitment to manufacturing the machine. On 18 March, Thorn EMI's marketing team began previewing the machine to CCTA and departmental staff. Civil Service pricing was agreed with Her Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO), which would be selling the device, and CCTA staff member Gordon Lawrence noted in a promotional document that "Thorn EMI is about to make the commercial launch and full production models are expected to be available in May [1985]".

That proved overly optimistic. Come May, Thorn EMI was already saying the Liberator would launch in June, though HMSO had already started listing the machine in its catalogues and customer newsletters as "non-stock items" and was offering government departments further previews of the machine. At the same time, the CCTA was working with pre-production machines, testing the software to expose bugs that would need to be squashed before the final Rom was burned.

Get it set

As John Peacock, the development team's finance manager, says, the first units highlighted issues that would need fixing before production could begin. The strike at the Treorchy didn't help, but at least it was short-lived. A bigger problem was that Thorn EMI bosses hadn't really believed the design team's claim that a working prototype would be ready early in 1985. It was, but Thorn EMI wasn't ready for it. And this was a time when initiating mass production required a lead time of at least 16 weeks, says Peacock.

Another problem, recalled by Derek Williams, was exposed when the machine was shown at the CCTA demo in February. The Treorchy plant had a wooden floor, but Riverwalk House was laid with nylon carpeting. The static electricity shocks the first Liberators were exposed to were something the rushed development team had never anticipated. Jan Wojna went back the to drawing board and in a few weeks had beaten the problem.

The June deadline was missed too, but Thorn EMI was sufficiently pleased with the product's progress to highlight the new device in its Annual Report, published in July of that year, calling it “a compact, easy-to-use and highly portable word processor with extensive applications”.

No monster PSU for this mobile computer

That enthusiasm would fade. The following year, the company's Annual Report would not mention the Liberator at all. By that time, Thorn EMI was more concerned by the ongoing cash drain that was UK chip maker Inmos, which it had taken over in July 1984 after it acquired 76 per cent of the Transputer developer for £95m.

But at the end of September 1985, Thorn EMI had enough cash to splash out on an extravagant public launch in France, taking journalists to the Chateau d'Artigny near Tours in the Loire valley. They were given kit play with on the flight, the better to appreciate the value of being able to work even at 30,000 feet. How many of us don't take that for granted now?

Back in Treorchy, Thorn EMI was punching out Liberators, Jan Wojna having spent the first part of year overseeing the establishment of the production lines while John Linney and Duncan Smeed finished off the software. Following the portable text processor's launch, their job was largely done and they were soon tasked with other computing projects for Thorn EMI. The following year, they would be working on an IBM compatible laptop, an Intel 286-based machine derived from their work on the Liberator but based on the platform now rapidly establishing itself as the de facto standard.

The world's first dedicated laptop bag?

Thorn canned the project just after the completion of the prototype, Wojna recalls, despite a major deal with “a major manufacturer” which John Peacock remembers was Daewoo. The Korean company was willing to make the machine and sell it in the States, but only if Thorn EMI committed itself to running a European sales operation. But Thorn wanted simply to license the design to other companies, Peacock recalls, and so the deal fell through.

Had the project reached the product stage, it would have been the first IBM-compatible notebook with an integrated hard drive to come to market, beating Toshiba, which launched the first HDD-fitted notebook PC, the T1200, in 1987.

Part Three: Into the maelstrom

Part One: Taking on the typing pool