Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2012/11/12/the_secret_history_of_liberator_the_first_british_laptop_part_one/

Liberator: the untold story of the first British laptop part 1

Taking over the typing pool

Posted in Personal Tech, 12th November 2012 12:01 GMT

Archaeologic In 1985, the UK home computer boom was over. Those computer manufacturers who had survived the sales wasteland that was Christmas 1984 quickly began to turn their attention away from the home users they had courted through the first half of the 1980s to the growing and potentially much more lucrative business market.

The IBM PC had been launched four years earlier, in 1981. The 5150 and the clones it had inspired at Compaq and other computing firms new and established were winning an increasing share of the market. Some British manufacturers were content to follow the American lead and offer clones of their own. Others, however, believed they could win with systems of their own design.

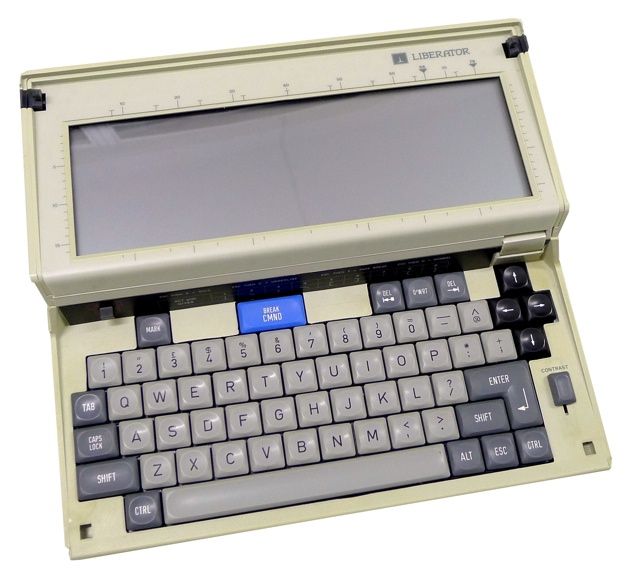

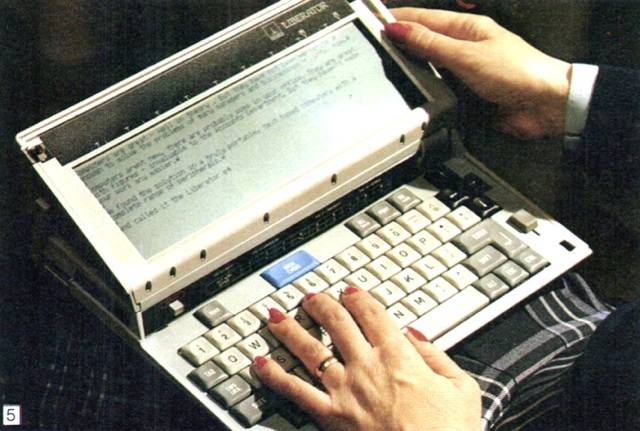

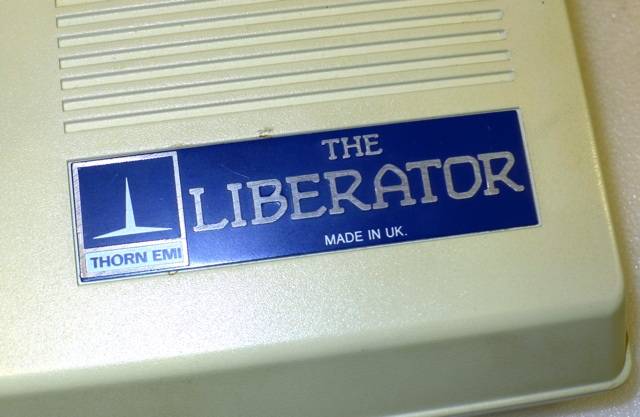

The Thorn EMI Liberator: the first British laptop

Time would show they were wrong, that what business wanted more than anything was standardisation and, more importantly, the cost savings that came with it. Other buyers wanted ultra-low cost computing. But in the mid-1980s many of Britain’s computer companies had established themselves in a market where numerous, often incompatible home micros successfully co-existed, each with its own ecosystem of software and add-ons. They believed business buyers would be happy with this world too.

Perhaps the most famous example, Sinclair’s Quantum Leap, or QL, flopped, and so did many, many others. Few are remembered today. Among the forgotten is the Thorn EMI Liberator, named not for the starship featured in the first three seasons of the then-popular BBC TV sci-fi show Blake’s 7 but for its ability to free workers from their desks and allow them to work on the move.

Little known now - it doesn’t even have a Wikipedia entry - the Liberator was the UK’s first home-grown laptop computer.

Designed for civil servants

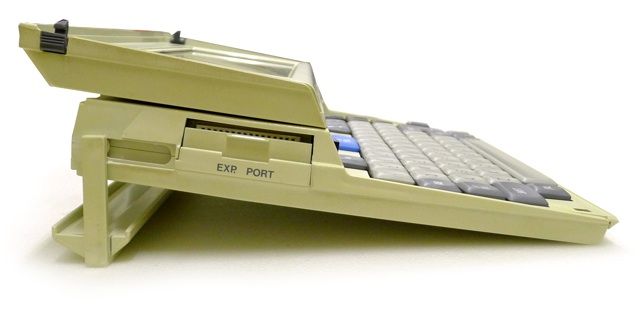

It wasn’t the first portable computer, or even the first British mobile machine - Epson’s HX-20 and the Grundy NewBrain claim those honours. It wasn't the first laptop: for that look to the US-made GRiD Compass. But the Liberator was the first notebook computer created in Britain that would be recognisable as such to users of today’s portable PCs. It sported the now familiar clamshell design. Closing the lid put it to sleep; opening it not only brought back the power, but put the user back exactly where they had previously left off working.

And this major innovation in mobile computing was created for that most conservative of worker, the British civil servant.

The machine that was to become the Liberator was devised by a civil servant too. It was designed to solve a very particular problem: the delay imposed upon civil servants by the established workflow for written communications. In an era before email when all formal correspondence had to be in writing, civil servants who might, say, reach an agreement on a course of action during a phone call would nevertheless have to confirm the plan in a formal letter. They would jot down or dictate the gist of the message, which would then be sent off to the typing pool to be written up neatly. This took time, doubly so if a latter needed to go back to the typists for corrections or amendments. In the meantime, no one could proceed until they had all the right paperwork.

As a Principal Systems Analyst and Designer, Bernard Terry - called by some "Britain's father of the laptop" - realised that putting text editing tools into the hands of his colleagues could eliminate the delay. He also knew that many civil servants, especially the more senior ones, were highly resistant to new ways of working. These were men who relied upon secretaries to do the typing and filing for them. These knowledge workers didn't need a fancy new typewriter, something that they would perceive as a way to get them to do the work lower grades were employed for, but a device which would allow them to take charge of the creative process.

This device, then, would not be pitched as a ‘word processor’, at that time a term for an electronic typewriter with its own memory and storage, and a machine for secretaries and the typing pool. Nor would it be promoted as a ‘computer’, a device viewed as a tool for the mechanics in the IT department not civil service decision makers. Instead, it would be a ‘portable text processor’, a gadget on which the enterprising civil servant could create the drafts he or she would then pass on to others for printing and posting.

At the time, Terry was working for the CCTA, the Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency, a body established to provide government departments with guidance on the use of information technology equipment.

The CCTA was formed in March 1972 by the then Conservative government as the Central Computer Agency. The Heath administration had accepted the findings of the Select Committee on Science and Technology, published in October 1971, that government needed a more joined-up approach to IT implementation. The CCA combined a number of government departments’ IT operations: the Computer Procurement Division and the Central Computer Bureau of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO), the government's office equipment supplier; the Technical Support Unit of the Department of Trade and Industry; and the Civil Service’s own Management Services (Computers) Division, which was already managing a number of large IT projects on behalf of the Treasury.

The CCA became the CCTA in 1979. Two years later, the Treasury would take control of the CCTA, and it was here that Bernard Terry was given the go-ahead by the CCTA's Director, Reay Atkinson, to find just such a text processor as he had envisaged.

Field trials

The first step, Terry recalls, was to find out if such a machine already existed. Now long retired but still spritely, the 85-year-old Terry told me he began to work through all the portable devices then on the market, almost all of them coming out of Japan, evaluating each as a possible basis for the Civil Service machine. Most were found wanting: they were either far too bulky or too small, the latter also lacking sufficient storage for the volume of documents a civil servant might be expected to produce, equipped with only tiny screens and unfriendly calculator-style keyboards.

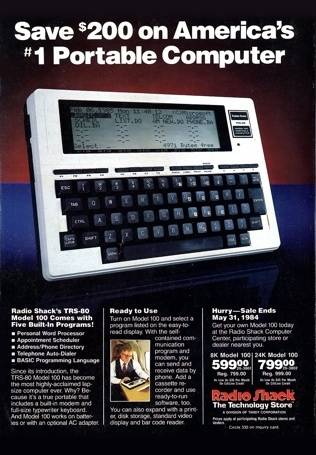

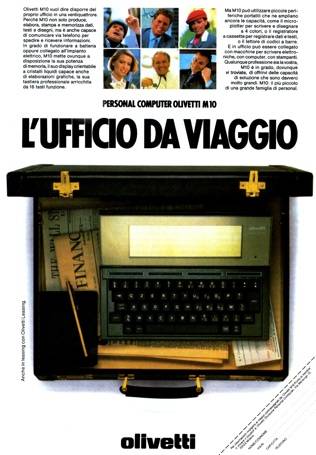

Would-be Liberators: (L-R) Tandy's TRS-80 Model 100 and Olivetti's M10, both made by Kyocera

With no stand-out contender, Terry decided to field-trial some of the existing machines. The selection criteria were an A4 footprint, a reasonable weight of around 4lbs (1.8kg) and a thickness no greater than 1.25in (31.3mm) to ensure it would fit into a Civil Service-standard briefcase. Three machines were chosen: the NEC 8210A, the Olivetti M10 and the Tandy TRS Model 100, all produced to the same broad template by Japanese manufacturer Kyocera. Terry was granted sufficient budget - £30,000 - to buy five each of these portables, plus peripherals and to conduct the evaluation. The machines were put in the hands of volunteers from within the CCTA and a number of other government departments, including the Department for Health and Social Security, the Department of Trade and Industry, the Department of Education and Science, the Department of Health and Social Security, and the Ministry of Defence, across a range of Civil Service grades.

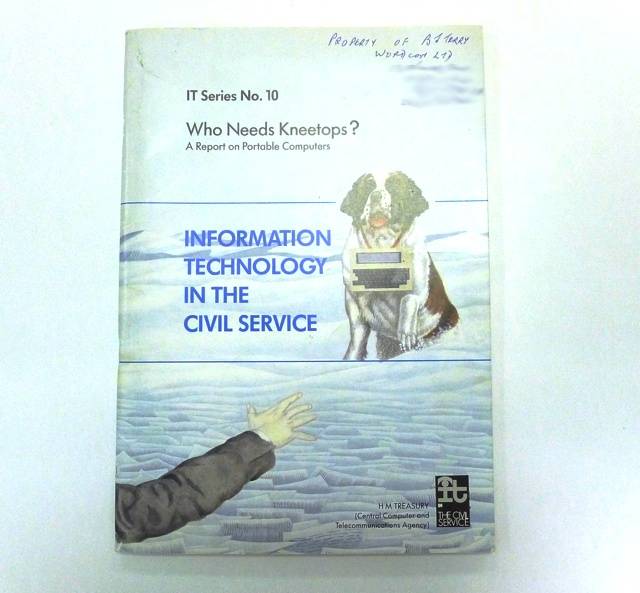

The nine-month trial, run by CCTA employee Gordon Lawrence, kicked off in 1983 and quickly demonstrated that Bernard Terry's initial notion was correct: that report-writing civil servants could not only be made more productive if given a portable text editor, but also that the device reduced the time taken to go from rough draft to finished document. The study revealed that senior civil servants could save almost three hours a week by using a portable machine for text preparation. A £750 machine would have paid for itself in six months, it was calculated.

The users were keen too: in the early days, two-thirds of triallists said they thought the machines had potential. By the end of the evaluation, five out of six thought that was the case.

Who needs kneetops? The CCTA's 1983-84 survey showed rather a lot of knowledge workers did

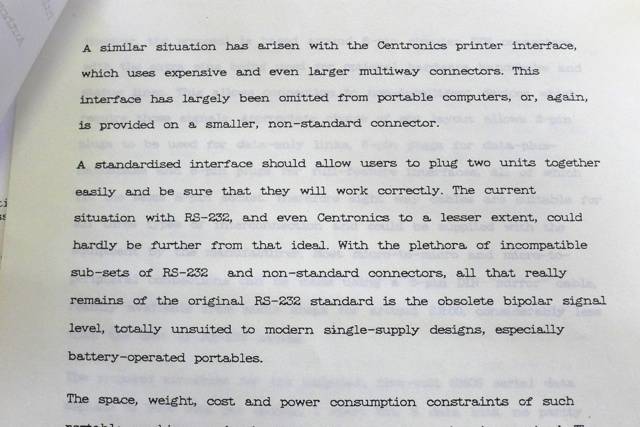

However, the test also showed that none of the products evaluated quite met their users' needs. Beyond problems getting printers connected and then working, they emphasised file juggling with the operating system or Basic programming over how specific tasks might be achieved. In short, says Terry, they were designed for computer buffs, not for workers needing to get a job done. The programs themselves often contained more features than were actually needed and so appeared intimidatingly complicated to the non-technical users of the time.

Terry approached a number of vendors with the results of the evaluation, but they showed no willingness or interest in adjusting their products - or devising new ones - on the back of this feedback.

There was nothing for it. With no existing machine exactly meeting Terry’s trial-tested requirements, and with vendors unwilling to adapt to them, the CCTA would have to oversee the creation of a machine of its own.

'Could hardly be further from the ideal' - The Public Service Working Party (PSWP) dismisses the Centronics and RS-232 ports

Terry was able to persuade the CCTA’s powers-that-be to grant him sufficient funding to initiate a development project: a UK company would be selected to build a prototype text editor under CCTA oversight, but would be able to release the final machine as a commercial product. Not only would the early work be funded by government, but the Civil Service would be there as a ready made market for the machine. Terry was instructed to prepare a broad specification for the device.

More than a quarter of a century on, Bernard Terry doesn’t recall approaching companies with whom he might develop the proposed text editor. As he remembers it, it was Reay Atkinson who had a contact in Thorn EMI's management through whom the company was eventually brought on board. "The next thing I knew, I was called into a meeting with the director of Thorn EMI and told they were interested in making the machine if I thought there was a market in the Civil Service," he remembers.

However, CCTA documentation from the time suggests the organisation, with the help of the Department of Trade and Industry, approached a number of UK computer and electronics manufacturers to sound them out as potential participants in the project.

Thorn EMI had certainly agreed to take part by September 1984, when an article penned by Andrew Hardie, who was Research Director of Oval Automation and Technical Consultant to a civil service advisory body called the Public Service Working Party (PSWP), alluded to the CCTA's "recent trial of A4-sized portable microcomputers, or ‘kneetops’ as they are referred to within the CCTA" and the organisation's "involvement with a major British manufacturer in the design and development of a new UK ‘kneetop’."

Hardie would would soon become closely involved with the Liberator project, initially working with Bernard Terry as a consultant to Thorn EMI's IT marketing team, later as a supplier of third-party peripherals for the devices, and eventually as a seller of the laptop’s word processing software on other platforms.

Finding a manufacturer

It isn’t known how many other British manufacturers the CCTA and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) approached, but one of them was certainly Dragon Data, the financially troubled maker of the Dragon 32 and Dragon 64 home computers. By the time the CCTA first talked to Dragon, the company had been bought from its founding parent, Mettoy, by the UK electricals and electronics giant GEC.

After the release of the Dragon 32, the Wales-based Dragon Data had established a nascent R&D team under its Technical Director, Derek Williams. Its task: to begin creating the next-generation products that would follow the 32 and its stop-gap upgrade, the Dragon 64. The Dragon 32 had been designed by a third-party consultancy; Dragon Data management wanted this crucial work and the expertise it required brought in house.

The Dragon Portable that might have been: Convergent Technologies' WorkSlate

Source: Bruce Damer/DigiBarn Computer Museum

Williams was tasked with seeking out new opportunities for Dragon and while travelling in the States in early 1984 his attention had been drawn to a machine spotted on the front cover of a magazine: Convergent Technologies’ WorkState, a machine not unlike Epson’s HX-20 but based on the Motorola 6800 processor family, as was the Dragon. It was designed less as a general-purpose computer more as a mobile spreadsheet - a numerical version of the text processor Bernard Terry was pondering back home. Williams was impressed by the WorkSlate’s potential as an easy-to-use device for business people, and realised it would fit very nicely into Dragon’s product line.

“I came back to the UK to find a letter on my desk from the CCTA, which was looking for a British company to make a portable text processor for the Civil Service,” Williams told me. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is amazing - the WorkSlate could be exactly what they’re looking for’. So I organised a meeting, went up to London and met Bernard Terry.”

It didn’t go quite as Williams had expected. “I outlined how I felt the WorkSlate could fulfil the need the CCTA had. Bernard was pretty solemn-faced throughout my presentation, and then he proceeded to just about wipe the floor with me, telling me everything that was wrong with the WorkSlate. I was just about to say ‘thank you very much’ and go when he said, ‘Now I’ll tell you what’s right with it’.”

Williams took Terry’s comments on board and promised to come up with a spec for a machine that would fit the bill. “And that’s what I did,” he recalls. “It took about two or three weeks, and I came with a spec which I discussed with Bernard, and he said, ‘Yes, this is something we can take forward’.”

Dragon Data's former R&D team, then at Thorn EMI, on the completion of the Liberator laptop:

(L-R) Duncan Smeed, Jan Wojna, John Linney, John Peacock and Derek Williams

Source: John Linney

At the same time, of course, the Dragon R&D team was working on other, rather more important, more concrete projects too, including a dual-processor Dragon for business users. But this was never completed: Dragon Data, by now renamed GEC Dragon, was declared unsustainable by GEC bosses and put into administration in May 1984.

Past histories of Dragon have often mentioned an unnamed portable that was intended to be pitched to business buyers. This is almost certainly a distorted mix of the WorkSlate brought home by Derek Williams and the CCTA machine the Dragon team was asked to consider.

After his meetings with Bernard Terry, Derek Williams was all fired up to persuade Dragon's management to take on the CCTA contract. The collapse of GEC Dragon put an end to that, but Williams was enterprising enough to realise that even though Dragon was no more, the company's tightly knit R&D team had the exactly right expertise to take on the CCTA project, left hanging by the closure. Williams and John Peacock, Dragon's Finance Director, began exploring how to make this happen.

One of the Dragon R&D team’s software engineers, John Linney, recalls that Williams and Peacock initially hoped to form a new company to tackle the government project. Local money men and venture capitalists were approached, Peacock remembers, but none were keen to invest in the then troubled computer business. He and Williams also approached electronics companies, such as Race, but without success.

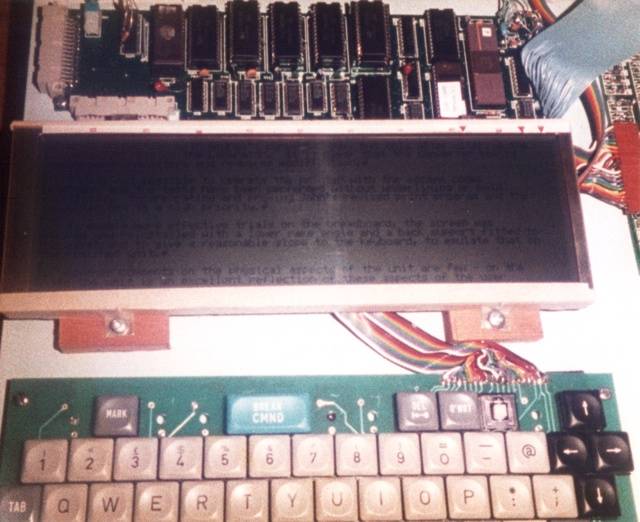

The Liberator prototype - then dubbed the 'Management Aid Tool'

Source: Bernard Terry

In the end, it was an industrial giant, the guns-to-music combine Thorn EMI, which took Derek Williams’ engineering team - Linney, hardware engineer Jan Wojna and Dragon software chief Duncan Smeed - under its wing. They would report directly to Williams as technical lead. John Peacock would manage the machine's component suppliers and cashflow.

"We were introduced to Thorn EMI by Bernard Terry," remembers Peacock. "We told about Thorn on Monday, met them on Thursday and started work the following Monday," he says.

The Dragon team sets to work

The DTI, through its interest in seeking a future for the former GEC Dragon plant in South Wales, also helped bring Thorn EMI and Williams' group together, in the summer of 1984. That's how Williams remembers it - he and Peacock met a DTI representative in a motorway service station near the Severn Bridge, half way between London and South Wales, and the government man suggested they approach Thorn EMI. The DTI later gave Thorn EMI a "support for innovation" grant to support its bid for the CCTA contract.

A few days later, Williams and Peacock were invited to meet Colin Southgate, then Group MD of Thorn EMI's IT division. "So we went down, met him, told the whole story and went through some budget projections and he said, 'yes'. He was one of those guys who make decisions very quickly, and he said in that meeting, 'I'm going to hire you'."

"The attraction to Thorn was they they were inheriting not a group of individuals but a team that had all the required disciplines to take on a project like the Liberator," recalls Jan Wojna.

It lives!

Source: Bernard Terry

"We were an unusual team," adds Derek Williams. "You wouldn't normally have someone like John Peacock, who's a chartered accountant, involved in the development group like this. But John has many other skills apart from financial. He's a really good wheeler dealer is John, and so he basically managed the purchasing side of things. John was very innovative in getting the cost of components down."

There was, Wojna remembers, a small period between Dragon's collapse and work on the new machine commencing at Thorn EMI - including the time taken to establish a development lab - but then "once all the basics had been sorted out - accommodation and things like that - it was a case of working out how we were going to turn this into a reality: [asking] what we need from the hardware, what we need from the software, what are the constraints, what are the requirements and what's the current technology available that would help us achieve that."

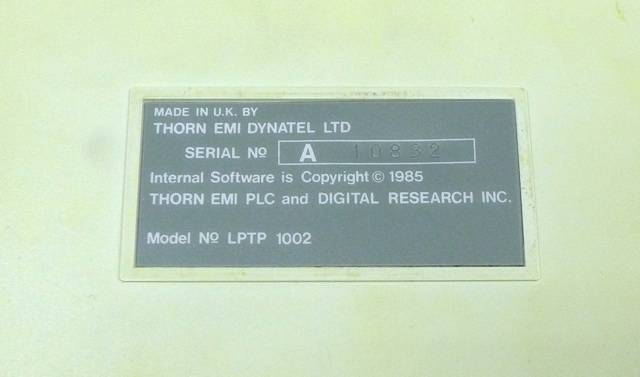

Thorn EMI itself the advantage of a presence in South Wales. And its plant in Treorchy, Glamorgan was under threat: by the early 1980s it was punching out dials for rotary phones - the operation was called Thorn EMI Dynatel - but was being undercut by Taiwanese rivals, as was so much of British manufacturing at that time. The factory might close, but if the proposed mobile text processor could be produced there, workers' jobs would be saved.

Financially, the CCTA text editor project was easy for Thorn EMI to accept, says John Peacock, because it was low risk. It could afford to chance "half a million quid and, in the end, more like £350,000 after the government grant" on the project going awry.

Whether it was DTI civil servants concerned by rising unemployment in the area; Thorn EMI's ability to persuade the CCTA that, with Derek Williams' team on board, it was best placed to deliver the mobile computer on time and on budget; Williams and Peacock's entrepreneurial chutzpah; or a mixture of all these factors, in August 1984, the CCTA gave Thorn EMI the go-ahead to design the Liberator and manufacture it at Treorchy.

Had GEC Dragon survived, the engineers might have considered basing the new machine on the technology they were preparing for future Dragon computers: the Motorola 6809E processor and its fully 16-bit successors, and Microware's Unix-like OS-9 operating system. At Thorn EMI, however, the team started afresh. Bernard Terry had already provided a broad statement of the problem they needed to solve - devise a text processing system civil servants could use to create documents away from their desks and later print out those documents - and it was up to them to spec up and create the machine.

The prototype's keyboard

The were given very little time to do so. Peacock, Linney, Wojna and Smeed all separately recall Derek Williams promising Thorn EMI chiefs that he and his team would have the prototype up and running within six months - a timetable pointing to completion by January 1985, at which point the CCTA was expecting to take possession of an initial 40 units. The pledge was treated with some skepticism by the powers that be, but it was one that the team, fuelled by coffee, adrenalin and a youthful drive to succeed, were able to make good.

At the time, the best choice for a low-power processor - clearly an essential requirement for a battery powered machine intended to free users from being permanently tethered to a power supply - was Zilog's ageing Z80A. John Linney recalls that other, more advanced microprocessors were briefly considered, including the Intel 8088 used in the IBM PC, but quickly rejected because of their relatively high power consumption.

"The Z80A could be put into a very low-power mode and [you could] wake it up with an interrupt," recalls Jan Wojna. "Whenever possible, we put the whole thing into this low-power mode or make it run more slowly."

The label says Digital Research, and the OS was CP/M, but using the Liberator, you'd have never known it

As the original Liberator Technical/Service Manual notes: "Great care has been taken both in software and hardware to keep the operating, standby and backup power consumption to a minimum, eg. in the operating mode the Z80 spends inactive periods in a 'halt' state (min. power consumption state, supply current about 65mA), when in standby mode power is disconnected from the Z80 system and the I/O processor [is put] in a 'sleep' condition (supply current <1mA)."

With the processor selected, the operating system effectively chose itself, says Linney. The team could have built one afresh, but it was easier and, crucially, less time-consuming to license one. For the Z80A, the only real choice was Digital Research's CP/M. ®

Part Two: The Liberator is launched

Part Three: Into the maelstrom