Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2012/07/02/newbury_labs_grundy_business_systems_newbrain_is_30_years_old/

The Grundy NewBrain is 30

The revolutionary product that came too late

Posted in Personal Tech, 2nd July 2012 08:00 GMT

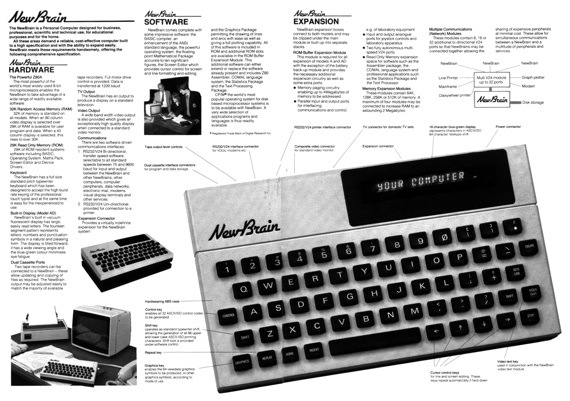

Archaeologic The NewBrain was launched 30 years ago this month, but its arrival, in July 1982, was a long time coming. The genesis of the computer that might have been the BBC Micro - that might, even, have been Sinclair's first home computer - goes back more than four years to 1978.

The company that became known as Sinclair Radionics was founded by Clive - now Sir Clive - Sinclair in 1961. But by the mid-1970s it was to all intents and purposed owned by the British government. Overseeing Radionics' operation was the National Enterprise Board (NEB), an organisation established by the Labour administration in 1975 to promote the nationalisation of key industries, and it took partial control of Radionics in 1976.

A long time coming: Sinclair Radionics Newbury BBC Grundy NewBrain

Source: WikiMedia

Two years later, the NEB agreed to fund the development, at Radionics, of a personal computer. The Apple II, the Commodore Pet and other similar machines had been launched in the US the year before to great success, and it was felt that a company like Radionics - particularly given Sinclair's keenness on producing technology products for ordinary people - could spearhead the micro revolution in the UK.

The proposed computer's hardware would be designed by Mike Wakefield, its software by Basil Smith. Having got the go-ahead, the two began work on the project in earnest.

In the same vein, the NEB agreed that year to fund Inmos, which would use the investment to develop an innovative new microprocessor architecture, the Transputer. You can follow that story here.

A micro for Blighty

Meanwhile, Clive Sinclair was finding government oversight a hindrance to his entrepreneurship and increasingly hard to cope with. Over the years, he had formed or acquired other companies and one, which had remained dormant for some time, was now brought back to life and renamed Science of Cambridge.

SoC would eventually be run by Sinclair ally Chris Curry, who would later leave to form Acorn. During 1977 and 1978, he oversaw the development of the MK14, a basic computer board conceived by Ian Williamson and which SoC would bring to market in 1978. Quite how much of the MK14 work was performed at Radionics and how much at SoC remains unclear.

Sinclair's NewBrain alternative: the MK14

What does seem certain is that Sinclair, if he was involved with the NEB-promoted micro project at all, felt that it could not be produced at a price that would make it accessible to "the man on the street". So he would focus his attention instead on a machine that could be.

Either that, or his hostility to the NEB - and therefore the organisation's apparently preferred microcomputer project - encouraged him to attempt to beat the quango at its own game. The MK14 was there in concept and in specification, and so Sinclair encouraged Curry to turn it into a product.

Whatever Sinclair's attitude to Wakefield and Smith's project, he quit Radionics in July 1979, went straight to SoC and took a closer interest in the work that would see the release of the MK14's successors: the ZX80 in 1980 and the ZX81 the following year.

Under new management

A few months before Sinclair's departure, the NEB sold off Radionics' TV and calculator product lines and development. With Sinclair out of the way, in September 1979, the Board renamed the company Sinclair Electronics. 'Electronics' was deemed more appropriate, more modern than 'Radionics'. The decision to retain the Sinclair name may have been a deliberate attempt to snub the man himself.

In any case, in January 1980, the company became Thandar Electronics and was soon effectively sold off by the new Conservative government by merging it with Thurlby Electronics. It survives today as TTi - short for Thurlby Thandar Instruments - which makes electronic test and measurement instruments.

NewBrain details

The NEB also had an interest in an electronics company called Newbury Labs, after acquiring a £343,000 stake in the firm in 1977, though in 1978 this share was sold at another company in which the NEB had a stake, The Data Recording Instrument Company. Ownership changed, but the NEB still had oversight.

In between the launch of the MK14, the collapse of Radionics, the exit of Clive Sinclair, and the formation of Sinclair Electronics, the NEB transferred the Wakefield/Smith micro project to Newbury.

Newbury continued the work. It was here that it became known a the NewBrain. Early in 1980, Newbury was ready to show off three prototypes - dubbed the M, the MB and the MBS - and discuss the product in public. Personal Computer World magazine's Dick Pountain would later say of the device shown in 1980: "The design concept was significantly in advance of anything that had been seen in the field of handheld computing."

From Newbury to Grundy

No wonder: the MB was a compact machine with its own display and a built-in battery. The MBS would use low-energy parts to maximise battery life. Newbury advertised all three units in the computing press throughout 1980.

Quite why the NewBrain wasn't released that year isn't clear. Most likely it was a casualty of the changes taking place at Newbury itself. With an anti-nationalisation government now in power, the NEB's role as a government puller of industry strings ran contrary to the administration's privatisation agenda. Its powers were curtailed. In 1991, it would be eventually privatised itself, as British Technology Group, or BTG.

During this period, Newbury MD Bob Smith left the company to join electronics firm Grundy. Did that prompt the transfer of the NewBrain to a third owner? It's hard to see the situation otherwise, but whatever the case, in September 1981, Newbury Labs formally sold the NewBrain to newly formed Grundy subsidiary Grundy Business Systems. Many key NewBrain staff - among them Mike Wakefield and Basil Smith - joined GBS at that time.

It wasn't simply a case of flogging the machine off. Newbury, don't forget, was controlled by the NEB, which by now had been merged with the National Research and Development Corporation and been renamed British Technology Group. BTG may have handed over NewBrain to Grundy, along with a £235,000 cash injection, but it got 30 per cent of Grundy Business Systems in return.

Money was always the problem. While Sinclair set price targets which governed what the ZX80 and ZX81 developers could achieve and thus yielded rather basic machines, Newbury arguably promised more than they could deliver - not for the first time in the computer industry.

The BBC Factor

As magazine Your Computer noted at the time of the sale to Grundy: "When the plans for the NewBrain were first announced, it sounded both novel and competitive, but the endless delays in its development mean that it has now lagged behind a new generation of personal computers. It is now almost certain that the NewBrain will never repay its development costs."

Part of those costs involved pitching the NewBrain to the BBC as the basis for the Corporation's own-brand microcomputer.

In 1979, ITV produced a documentary based on Christopher Evans' book The Mighty Micro, itself inspired by the microcomputer revolution taking place in the US. The BBC produced a similar programme, The Silicon Factor, later that year.

The Corporation then commissioned a ten-part series entitled Hands on Micros. Scheduled to be broadcast in October 1981, the show would would introduce viewers to the computer and help get them using one. It would form the basis of what would become known as the BBC Computer Literacy Project, devised by The Silicon Factor Producer David Allen.

Early in 1980, Allen and his team decided that the Computer Literacy Project and the TV series that Hands on Micros needed a machine which the public could buy and use to gain real experience of what was being discussed in each episode. Only that way would the audience truly engage with the new technology and the goals of the Computer Literacy Project - no less than a mass education of Britons to IT - be realised.

Acorn 1, Grundy 0

The Basic language was the obvious starting point, but with no 'standard' dialect available, it was decided the BBC should devise and promote one of its own, using the BBC brand as a stamp of authority.

Meetings held by the BBC with the Department of Trade and Industry led the Corporation's team to the NEB and then to Newbury Labs. The result, it has been claimed, is that the BBC selected the NewBrain to be the BBC Micro but dropped it when it became clear the machine would not be ready for the proposed October 1981 broadcast of Hands on Micros.

The NewBrain was well-placed to become the BBC Micro, having been first promoted early in 1980, while planning work on Hands on Micros was under way. But if the NewBrain's unsuitability was to force the BBC to look elsewhere, it happened very early on. BBC documentation shows Acorn's Atom follow-up, the Proton, had been chosen to be the BBC Micro by February 1981, long before Hands on Micros' scheduled appearance.

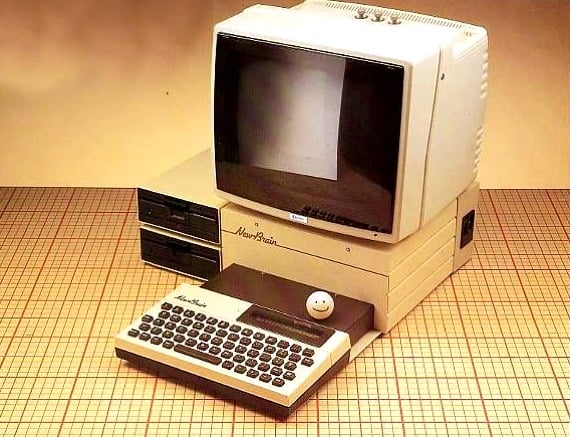

A variety of add-on units were promised

There is no specific evidence to suggest the BBC selected the NewBrain and then dropped it. Quite the reverse: the NewBrain's spec needed to be changed to meet the BBC's requirements. The hardware had to be tweaked. It seems likely it was this effort that stopped Newbury bringing the NewBrain M, MB and MBS to market in 1980 and perhaps even 1981.

Newbury's sale of the NewBrain to Grundy on September 1981 suggests that it was indeed unable to bring the machine to market, and that fresh minds - and more money - would be required to do so.

Grundy had both, and was able to finalise the development and begin manufacturing the machine. At long, long last, the NewBrain was launched, in July 1982.

NewBrain released

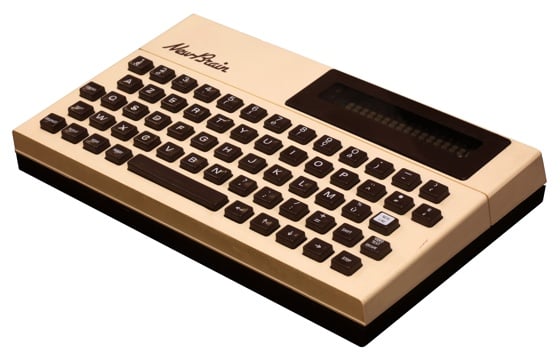

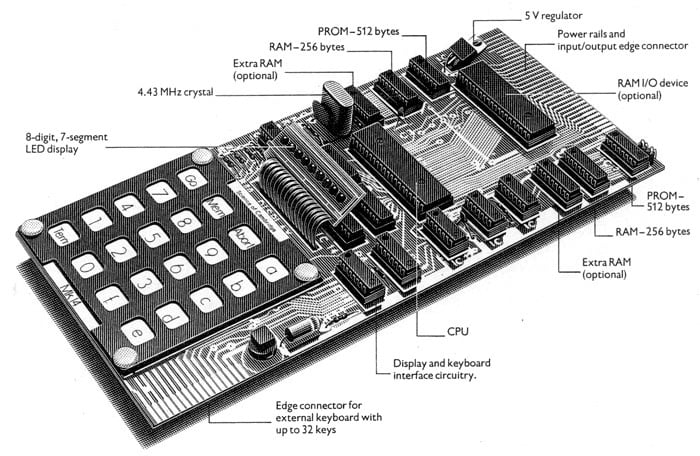

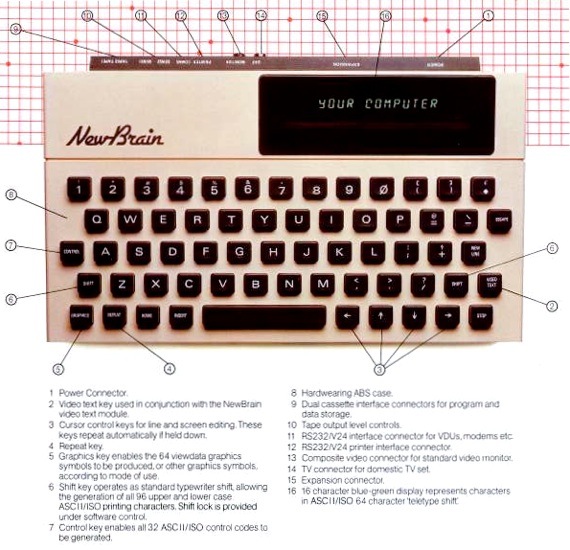

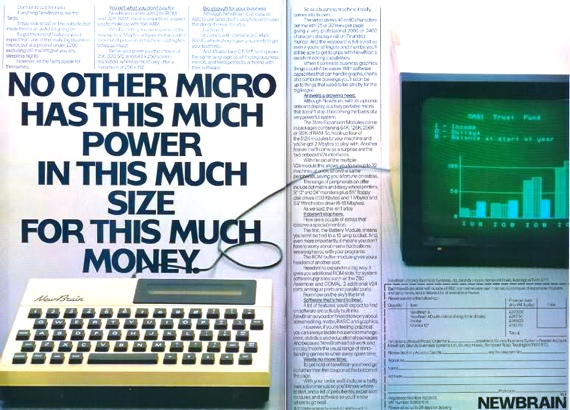

Two models were offered: the £233 Model A and the £267 Model AD. The A had 32KB of Ram, a Zilog Z80A processor clocked at 4MHz, and proprietary printer, communications and twin tape ports, plus monitor and TV feeds. An expansion port on the back could take 64KB, 128KB, 256KB or 512KB Ram packs. The packs had pass-through connectors, allowing up to 2MB of memory to be added, way more than rivals machines could provide.

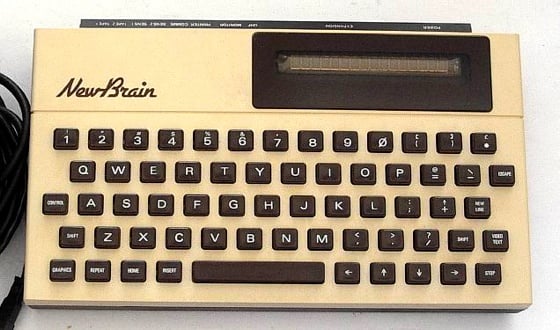

The AD also sported the well-remembered vacuum fluorescent 16-character, 14-segment display. It could also take the (optional) long-promised battery pack.

The Model AD came with a built-in 16-character displsy

Novelly, the NewBrain shipped with a Basic compiler to convert software into machine code in one go, rather than simply interpret programs line by line, as most other micros did back then.

Your Computer said of the machine at the time: "It could not be recommended to a beginner but could prove attractive to an experienced user who is prepared to explore some of the possibilities only hinted at in the manual.

"As a business machine, the NewBrain should do well: its highly adaptable operating system and large potential memory makes it suitable for applications which were hitherto only within the scope of machines several times as expensive."

Missing the market

So much promise and yet… it's the same old story. For instance, Grundy said the NewBrain would run CP/M - a version of the OS would be out by January 1983. It didn't appear for many more months. Users had problems with the cassette port. Promoted peripherals, such as floppy and hard drive controllers, expansion modules and a special multi-module housing, launched much later than announced, if they arrived at all.

Promoting the NewBrain

Yet the potential pulled in punters. Sales were slow initially, but picked up in the Christmas period, more so than Grundy was at first able to satisfy. As a result, the decision was made early in 1983 to ramp up production tenfold. But demand slumped, in part on the back of delays getting the promised peripherals out.

Basil Smith and Mike Wakefield, who had been working on the NewBrain since the very beginning, quit around this time. So closely were they associated with the machine - and so deep their knowledge of it - it would have been hard for their remaining colleagues to continue the project.

They wouldn't need to: Grundy pulled the plug later that year. Grundy Business Systems was closed down. It is thought some 50,000 NewBrains had been sold by that point. The remaining NewBrain stocks were sold to Dutch firm Tradecom, which installed them in schools in Holland. ®

The author would like to thank all those fellow enthusiasts for scanning and uploading so many adverts and manuals from the 1980s, without which this article would have been much less detailed.