Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2012/05/24/wtf_is_lifi_visible_light_communications/

WTF is... Li-Fi?

Optical data transfer's new leading light?

Posted in Personal Tech, 24th May 2012 06:00 GMT

Feature Forget about Wi-Fi - the future of home wireless networking is, according to boffins, the light bulb.

So say a number of researchers and technologists who are looking to light to provide the next step in high-speed data networking in the home.

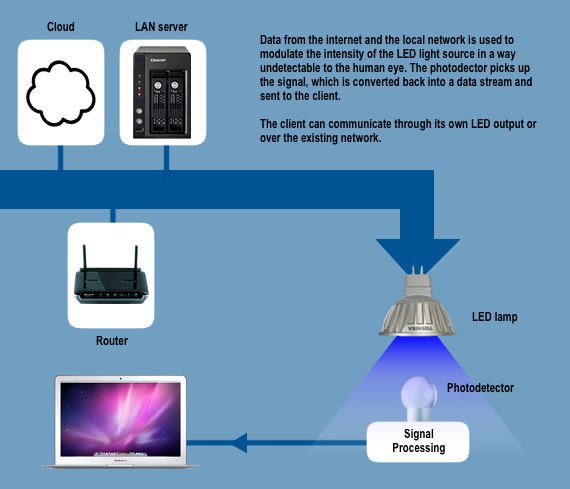

The principle is simple: turn a light on and off so rapidly that the human eye can't see the flicker, but a photodetector can nonetheless pick up the stream of 1s and 0s the blinking bulb is transmitting. Compress the data, and you up the throughput even more. Old-style filament bulbs and fluorescent tubes aren't up to the task, but new, LED-based lighting is.

It's not hard to envisage home lighting with an integrated photodetector - to pick up signals sent back from networked devices - and perhaps a powerline adaptor on board to maintain a connection over electrical wiring back to the router.

The technique is called Visible Light Communications - or VLC, not to be confused with the open source media player of the same name - but the companies springing up to deliver the technology are already branding it "Li-Fi". The similarity to the name "Wi-Fi" is deliberate: they hope VLC will become as ubiquitous a networking technology as 802.11 has become.

Lightbulbs, lightbulbs everywhere

One of VLC's key proponents, Harald Haas of the University of Edinburgh, reckons that isn't hyperbole. With tens of billions of regular lightbulbs installed in homes and offices across the globe, as they're replaced with LED light sources, Li-Fi can be a communications technology that can be found almost everywhere.

Li-Fi bulbs will inevitably be more costly than regular LED bulbs, but then the potential volumes will, Haas reckons, push prices right down.

More to the point, Li-Fi could be used in almost every location where regulations forbid the use of Wi-Fi: aircraft cabins and hospitals, to name but two. And light isn't affected by the spectrum regulations that govern how radio frequencies can be used.

Of course, getting it out of the lab and into the living room - and every other space illuminated by a lightbulb - is another matter.

From Palm Pilots to high-speed data

Germany's Fraunhofer Institute, best known for developing the MP3 audio codec, runs a photonics lab in Dresden. Earlier this year, it said it had created a wireless optical link capable of delivering data at the rate of 3Gbps.

Fraunhofer's technology isn't true VLC - it uses infrared light. So it has the backing of the IrDA, the Infrared Data Association, the organisation founded in 1993 to oversee device-to-device infrared communications standards. You know, beaming business card details from one Palm Pilot to another, or early wireless printing kit, or even linking a computer to an old Nokia phone as a modem.

A Fraunhofer boffin tweaks the Institute's IR tech

Hardly anyone builds IrDA ports into devices these days - USB, Bluetooth and Wi-Fi are faster and don't require line of sight. But the IrDA is looking to VLC to give it a new lease of life.

At the end of 2011, it pledged to work to define a new standard for 5Gbps and 10Gbps infrared communications, an effort building on the 1Gbps the existing Giga-IR standard supports. The Fraunhofer kit supports Giga-IR.

At these higher speeds, IrDA believes its updated standard could replace the likes of HDMI and USB 3.0.

D-Light delight

Meanwhile, Haas, together with Ediburgh University colleague Gordon Povey, continues to work with visible light. They and their team at the college's D-Light - "Data Light" - project have created kit capable of 130Mbps data transfer rights. A lot slower than Fraunhofer's rig, to be sure, but one delivered by off-the-shelf parts rather than custom lab components. Povey and Haas believe they can push that speed to at least 1Gbps. Other Li-Fi proponents claim 10Gbps will be possible with specially designed LED lightsources.

Both boffins also run PureVLC, a company founded to commercialise Li-Fi technology on behalf of the University, and this month PureVLC claimed to have sent the first text message send by LED to an unmodified Android handset.

Coming soon: PureVLC's 'Smart Lighting Development Kit' board

To be fair, the data rate was a low 2.5Kbps and it requires a special app to control the handset's cameras and detect the message. But PureVLC's demo showed that messages can be sent with low-cost kit and that doing so doesn't register with the human eye.

PureVLC is also promising to release a "Smart Lighting Development Kit", a full duplex VLC system that connects to standard LED light fixtures, in Q2 2012.

Practical applications

PureVLC isn't the only company working on this. In January, Casio demonstrated its take on the tech: flashing one smartphone screen - a flicker, again, imperceptible to humans - to send photo and message data to a second handset. Again, it was a relatively low-speed trial, but one made using everyday hardware.

Social communications: Casio's VLC app, Picapicamera

Casio has been working on this for some years now, as have other Japanese technology firms. A group of them formed the Visible Light Communications Consortium in 2004. But there, as here, there seems little to show for the years of experimentation.

Toshiba, for example, has a pair of maritime binoculars that can pick up a signal beamed from Japan's lighthouses at up to 2km, beyond the range of Wi-Fi. The signal tells the viewer about sailing conditions in the immediate vicinity of the lighthouse. Again, it's not a fast transfer: just 1.2Kbps. Enough for a short burst of compressed data, but not much more.

Then there's Reset. It has produced a diving mask that transmits the wearer's voice as a series of light pulses. A detector converts the light back to an audio output. This enables underwater conversations at distances of up to 30m. The catch: each mask costs ¥150,000 (£1200) and you need two to make it worth wearing one.

In the West, we have the Li-Fi Consortium. One of its first tasks: the slightly embarrassing point that "LiFi" is a trademark owned by someone else, in this case US company Luxim, which makes plasma light sources.

Wireless alternative

Casio's app is now available from the iTunes App Store. The software, Picapicamera, is designed to exchange snaps adorned with cartoons and text, but Casio says it's also ready to receive signals from digital billboards and domestic LED-backlit TVs - a key application for VLC, Casio reckons. It imagines phone owners grabbing discount vouchers, the location of the nearest stockist and such simply by pointing cameras at light sources, much as a few already do with QR codes.

But there's the rub: there are already many technologies that deliver small bursts of data for those willing to accept it. And while the lightbulb may be ubiquitous, so too are wireless networks - and these are generally turned on 24-7, not something you can always say for lights.

That doesn't mean the two are not complementary, and the ever-busy radio spectrum means some users may seek less crowded alternatives. Canny Wi-Fi users are already shifting into the relatively empty 5GHz band, but the arrival of faster version of Wi-Fi, such as 802.11ac, will steer more new users into that band, and that may persuade some folk to take a fresh look at light. ®