Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2012/04/20/oracle_google_java_lawsuit_summary/

Oracle v Google round-up: The show so far

What’s going on here? Who’s winning?

Posted in Legal, 20th April 2012 16:24 GMT

After years of waiting for the contenders to open fire, the Oracle-Google shooting match is now on, and the bullets are pretty expensive. The opening salvos have landed, so let's take stock.

It’s worth keeping at the back of your mind how strange it is to be here at all. Judge Alsup has spent three years trying to persuade both parties to settle privately – they’re haggling over the odd billion. But he hadn’t counted on the obstinacy of the Two Larrys. So to the case.

Sun wanted to pull off the hitherto impossible goal of keeping its Java platform open enough to achieve widespread industry adoption, but closed enough so it could retain control to avoid fragmentation. Opening your code is easy, and controlling your proprietary code is easy, but Sun wanted a unique middle way. So the procedures Sun wrapped around Java are pretty complex – and they have changed over the years. But Sun achieved what it had pretty much wanted: extensive industry use of Java, and absence of fragmentation.

That was, until Android.

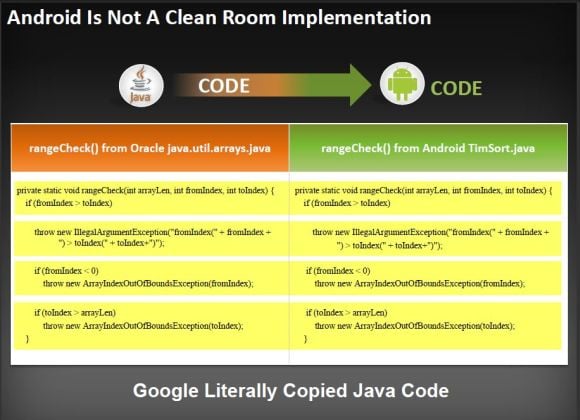

In a nutshell, Google admits copying Sun Java code into Android. Google maintains that the code it copied didn’t require a licence. Google also argues that the Android platform, in which Java language code is written against Java classes (before being crunched into something that Google’s VM can run) doesn’t need a Java licence.

Oracle's case against Google is laid out in a 90-page slide presentation released at the start of the trial this week.

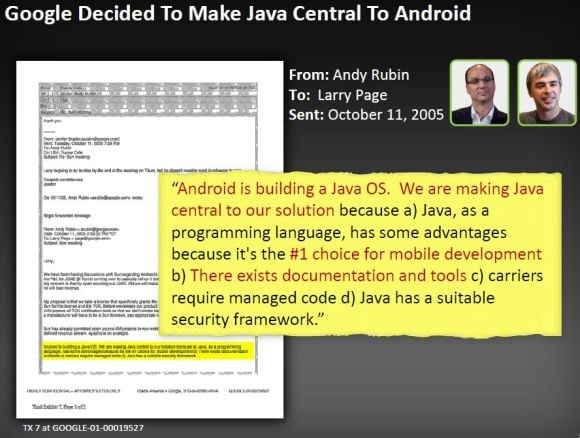

Sun launched Java in 1995 and Oracle gobbled up Sun in 2009. The hostilities began that year – but from new evidence we can see they were always simmering under surface. Android was founded in late 2003 and snapped up by Google two years later. That year, in 2005 [p38 of the slides] Android founder and chief Andy Rubin wrote to Larry Page:

Google wanted to open-source Android, but it knew Sun was uneasy about that. In October 2005, Rubin suggested to Larry Page that Google ought to pay Sun for a Java licence, and swallow the cost. According to Oracle’s narrative, negotiations were dragging on into 2006, and Google should have at that point contemplated a non-Java option – an avenue quashed by Google manager Brian Swetland in August 2006. By 2007, Android’s attitude could be summed up as: ‘Hey, what the hell’.

Rubin wrote:

I don’t see how we can work together and not have it revert to arguments of control. I’m done with Sun (tail between my legs, you were right). They won’t be happy when we release our stuff, but now we have a huge alignment with industry, and they are just beginning.

In 2007, Rubin noted how cunning Sun had spun the law around Java. The awareness that Google was striking out into new and dangerous territory was evident in 2008: taking a license was “now water under the bridge” and excerpts from emails show engineers and management coyly avoiding the subject in discussions.

“Please don’t demonstrate to any Sun employees or lawyers,” Rubin warned an engineer in 2008, as he prepared to take Android on the road. (As an aside, here’s the engineer’s blog from his first fortnight on the job at Google: “As with most companies that rely on their IP, you learn very quickly that Google has a lot to lose from loose lips, and I don't want to see that happen.”).

The “What the hell” strategy is in Google’s DNA: there are echoes of the Google Book project and Google’s acquisition of YouTube. In each case it knew it was potentially in the wrong, and acquiring huge liabilities. But it pressed on.

Enter Schmidt

Oracle adds that during this period Google hired key Sun Java personnel, who were working under former Sun executive Eric Schmidt. Schmidt had joined Google in 2001. While this is true, the implication is that Google needed these stars to create its “Java OS”. In fact, key Sun staff drifted to the Chocolate Factory throughout this period, preceding Google’s interest in Android. But the testimony of one defector has attracted the most coverage.

Tim Lindholm, a Distinguished Engineer at Sun, helped write the original Java VM, and joined Google the same year Google acquired Android. In 2010, with Android a huge hit, Larry Page asked him to explore alternatives to Java.

Lindholm concluded that all the alternatives “suck[ed]” and “we need to negotiate a license for Java”. Google fought a long, hard but ultimately unsuccessful battle to keep this email out of court. This week Larry Page couldn’t recall who Lindholm was, or making the request. Oracle details the code copied from Java into Google. This makes it difficult for Google to argue it was any kind of clean-room implementation of the key Java libraries (classes). Private classes were copied verbatim. And Android remains the only Java system in the world that doesn’t have a Sun/Oracle Java licence.

For its part Google has shown the court statements by Sun’s last CEO, talkative Jonathan Schwartz. Schwartz “applauds” Android and vows to support it, in 2007. It’s thin stuff, though. As Florian Mueller points out in his analysis, Schwartz’s comments cut little ice with the Judge.

That’s the meat of Oracle's copyright case - the trial is still ongoing. Patents will follow in the weeks to come. In court this week, the exchanges were largely theatrical. Lindholm was hung out to dry by lead lawyer David Boies (which is all Boies had to do). Google executives including Page have adopted the Clinton-Gates defence of not really being able to remember anything that was going on.

So... it doesn’t look great for Google. The principle is if you use someone’s stuff you pay for it, or invent your own. But as I pointed out earlier this week, it’s a peculiar situation. Oracle’s victory might not get it the damages it wants – the judge has consistently scorned the size of these claims – and it may extend copyright into new areas, causing huge confusion for the industry. But the case falls into a murky area where simple, clear sensible law should exist. When that happens, the lawyers are the biggest winners. ®

Related link

Oracle's case in slides (PDF)