Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2012/04/09/feature_wtf_is_ultraviolet/

WTF is... UltraViolet

Cloud Nine or Hurt Locker?

Posted in Personal Tech, 9th April 2012 11:00 GMT

Feature

We're all used to buying movies and TV series on disc. Many of us are accustomed to downloading films and shows from the likes of Apple's iTunes. A fair few of us stream video content from Netflix or Lovefilm. Wouldn't it better to combine all three into a single system?

Such a combo is what the Hollywood-backed UltraViolet is trying to become, and with the support of the best known content companies in the film business, plus retail giants like Tesco and Walmart; computing fims like Adobe, Microsoft, HP, IBM and Nvidia; IPTV players and broadcasters, including BSkyB and BT; streamers Netflix and Lovefilm; and hardware makers Panasonic, Philips, LG, Sony, Samsung, Toshiba and more - all members of the 75-strong Digital Entertainment Content Ecosystem (DECE) consortium - it's hard to see it failing to succeed.

Not that it's the only player in town. Apple's iTunes stands apart, back turned, arms folded, nose high. Indeed, it's unlikely to ever be a part of UV since it is one of the service's key competitors. So too are all the folk making disc rips available through Torrent sites.

The UltraViolet way

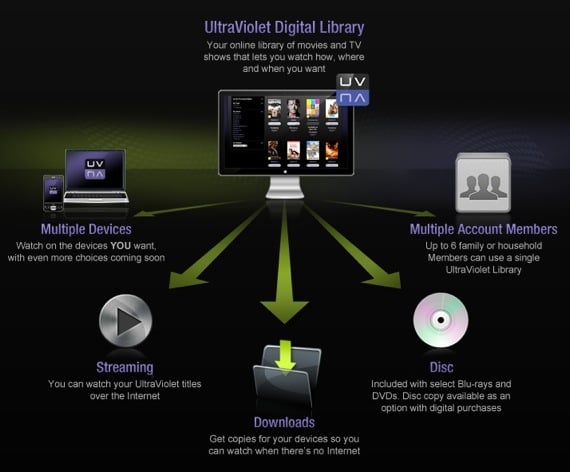

UltraViolet, which launched in October 2011, is pitched as a universal cloud-hosted movie library. The notion is that all your content - not just what you will buy but also what you've already bought - will be permanently available to you on the internet.

Buy a film on Blu-ray Disc and, once you've created a UltraViolet account, either directly at the UV website or through the disc distributor's online shop, and you'll be able to stream the content too, not just watch it on your TV using a BD player.

You'll be able to download it too, for offline viewing - handy if you want to take a stack of films with you to while away the hours on a long flight, say.

Delete the file deliberately or accidentally, and you'll always be able to re-download it. Or simply stream it to avoid having to find disk space for it.

If you're not collecting discs any longer, you'll be able to buy UV movies just as you would a download from iTunes, Vudu or Blinkbox.

How UltraViolet works

Behind this process is a framwork that combines file formats and digital rights management (DRM) technology, and a mechanism to connect cloud-stored licences to content owners' online archives.

UV accounts don't store the content itself, only the licence that grants the account holder the right to view the material. Stream a movie through a UV partner's website or their app, and the system confirms that you're allowed to watch it. It then initiates a stream, or download, from whatever server farm holds the video file.

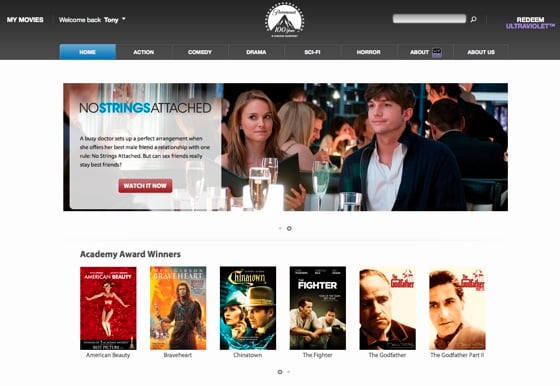

Paramount's UV store

There are two advantages here. First, content owners need only hold a couple of copies of each title, one in SD, the second in HD. Users' accounts don't accumulate copies of movies themselves.

Secondly, if a studio decides to offer, say, 4K by 2K copies, it can do so easily. If it likes, it could provide existing customers with access to those higher resolution files simply by updating their licences.

Licenced premises

Of course, that's unlikely to happen for free. UV currently offers two content profiles: one for SD content, the other for HD and SD content. Crucially, though, UV makes it possible to add higher resolutions or simply better copies - there's an audio drop-out in the current version, say - of existing files, easily and without troubling the customer.

But, yes, all this involves DRM, to prevent folk giving content away to all and sundry. But the DECE partners have tried to provide a true 'buy once, play anywhere' system that's as flexible for the viewer as working with DRM-less files can be.

UV's licensing terms allow the content licensed to any given account to be accessible by up to six household members. Any device with a web browser will be able to stream that content, and three files can be streamed simultaneously. UV's Ts&Cs permit downloads to a total of 12 devices. You can own one physical copy: either the Blu-ray Disc you started out with, or a secure memory card if you bought a download.

You can even sell the disc on or give it away, but it's unclear - the UV partners are vague about this - what that does to your digital copies. If they came 'bundled' with the discs you've just got rid of, you no longer have a right to the. Whether UV prevents the new owner from gaining downloadable copies - or automatically transfers your licence to them - remains to be seen.

Sequel server: Warner Bros' first UK UltraViolet release

Core technology

UltraViolet is, the DECE claims, built on standards. It has a Common File Format (CFF) derived from Microsoft's Protected Interoperable File Format (PIFF) and which holds AES-encrypted or unencrypted audio and video and DRM data. The Motion Picture Experts Group (MPEG) is wrapping the DECE's file format into the MPEG 4 container and other UV elements into its Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP (DASH) protocol.

The DRM schemes UV files hold are Marlin, used by many connected TVs; the Open Mobile Alliance (OMA) and the Content Management License Administrator's (CMLA) OMA 2.0, which is found on many mobile phones; Google's Wildvine; Microsoft's PlayReady; and Adobe's Flash Access 2.0.

Any of these DRM technologies can be used to play the file. Using the profile information, an SD player will only play SD content, but an HD player will handle HD or SD, as appropriate.

It's not all there yet, though. While some UV partners are currently offering downloads, the files transferred aren't yet fully compliant with the CFF, which isn't due to be finalised and launched until summer 2012. At this stage, it's unclear whether copies bought now will automatically be replaced with CFF-based ones, but there's no reason to believe they will not be. Annoying early adopters will do nothing to promote UV, especially when the industry is so keen to stress the service's consumer friendliness.

Once CFF-based download content is available, it will allow material purchased from source A to be freely viewed on source B's player. Viewers won't be tied to specific companies, just to the UV ecosystem as a (very big) whole, which is essentially what we've grown used to with physical media.

Converting libraries

UV won't only be relevant to new purchases. On 16 April, US retail giant Walmart will allow shoppers to bring in their DVDs and BDs and pay to have digital copies added to their UV accounts. An SD copy will set punters back $2 (£1.26), an HD copy $5 (£3.15), even if someone only owns the DVD. They get their discs back.

Walmart's scheme is the first of its kind, and requires you to sign up for the retailer's online video store, Vudu, though the digital copies you buy can be played on Warner's Flixster app, available on a number of platforms.

Other firms will follow Walmart in the States. Best Buy is a DECE member and is expected to announce a similar disc-to-digital scheme soon. And the smart money suggests fellow DECE member Tesco will offer such a service too, no doubt tied to its online video store, Blinkbox, which it bought in April 2011. It's not hard to imagine Walmart-owned Asda doing so too some way down the line.

Will Tesco's BlinkBox offer disc-to-digital trade-ups?

In the US, Amazon has voiced its interest in UV. Its UK-based Lovefilm streaming service, like the rival Netflix, is a DECE member. Both are likely to support UV in due course, offering UV sales as an alternative to their streaming and rental services.

Warner Bros UK has said it will support UV on all future BD releases, and Sony is expected to do so when the CPP is launched this coming summer. Virgin Media may add UV playback to its TiVo set-top box. Tesco's Blinkbox has confirmed that it will support UV. So has Dixons, which launched its own online movie shop earlier this year.

Apple alone

UV's universality replicates the old-style retail world. It allows you to buy content wherever it's cheapest and play it on whatever (compatible) device/app combo you fancy. The exception is - surprise, surprise - iTunes.

Apple's DRM technology, FairPlay, isn't part of the UV spec. Apple won't make it available - or at least hasn't so far. Under Steve Jobs it would have been unimaginable for the company to support UV, which is the antithesis of his lock-the-customer-in philosophy. CEO Tim Cook seems less dogmatic than Jobs, but it's hard to see him willingly loosening the hold Apple has over folk who buy content from iTunes, especially when the company's iCloud service allows it to match the functionality UV offers, if not its universality.

Indeed, pipelined projects such as the rumoured 'iTV' Apple television and a TV subscription service, suggest the company is preparing for a two-horse race: iTunes vs UV; us and them.

For now, Apple has the edge: it has hundreds of millions of customers worldwide - there are just under a million UV accounts in play - it has a better known brand and it is already selling lots and lots of content. UV really won't come into its own until it is relaunched in the summer with CPP support and the true universality the common file format makes possible.

Apple's iTunes to support UV? Not likely

Apple alone then? Not entirely. Disney is developing its own UV-like service, called KeyChest. Like Apple - to which it was, in Jobs' day, connected through Pixar - Disney reckons its brand is strong enough that people will come to it, no matter what.

The real target

But there's room for Apple, Disney and UV. Indeed, while it's tempting to see UV as an industry-wide attempt to resist the rise of the Cupertino giant, it's actually about discouraging consumers from downloading pirate copies of films. Most folk do so because it's free, and that's going to be a hard sell, no matter how flexible UV is.

But for downloaders who object to previously imposed tight DRM limits and those who'd rather go legal if given a decent way to do so, UV is attractive. And since it renders the need to rip purchased discs largely unnecessary, it may have the effect of limiting the amount of content available on Torrents. Maybe.

As the UV website admits: "Whether these options are available, and the details of how they work, may vary by retailer and by title." Likewise, content licensing limitations means that the service, while available in multiple countries, doesn't necessarily mean you can stream a US movie to a UK user. The industry still wants some say in what you watch, when - and that may be too much control for movie fans. ®