Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2012/03/05/pong_anniversary_al_alcorn/

Atari Pong at 40: Alcorn talks plastics, pirates and square balls

Pong pioneer to Bushnell: 'Screw you, I'm not making it round!'

Posted in Software, 5th March 2012 12:37 GMT

Interview The phrase "Once you're lucky, twice you're good" should be applied to Allan "Al" Alcorn, the engineer behind Pong, the world's first successful computer arcade game which celebrates its 40th birthday this year.

It is Atari founder Nolan Bushnell, the buccaneering entrepreneur with a flashy grin, who attracts headlines for having invented Pong, a simple game of digital ping-pong that consisted of hitting a tiny white ball – actually a square – across the inky-blackness of a TV screen, between two "bats" controlled using circular paddles. But it was Alcorn who built Bushnell's idea.

And Alcorn didn't just build Pong once, he built it twice: first as the arcade game in 1972 and then as a home console. The latter system was in such demand that shoppers – predating Apple's fanbois by decades – waited hours in long, cold Christmas shopping lines just to get on the waiting list. Once it was in stores, the console was quickly copied by jealous rivals.

Pong proved that video games could be lucrative – if done right. Pong wasn't the first computer arcade game or even the first home games console. Bushnell already had Computer Space in arcades while at home there was Magnavox's Odyssey. What Pong brought to gamers was simplicity of play and presentation; it offered revolutionary features Odyssey lacked: sound, on-screen scoring and the ability to spin the ball to wrong-foot your opponent.

Pong was an early console pioneer. Nintendo's Wii, Sony's Playstation and Microsoft's Xbox are its heirs, with their multitude of titles from authors and studios who will all gather at this week's Game Developers' Conference in San Francisco, California. Spending on these systems and the associated ecosystems of titles and services in 2011 was estimated at $74bn last year and is expected to hit $112bn in three years' time.

Games development has changed from those Californian pioneering days of the early 1970s. Today, designing and building the system at least is an industrialised process, with components sourced and even assembled by established third-party suppliers using proven manufacturing processes. Games roll out from mega studios like movies – involving scripts, sets, designers, engineers and lots of marketing.

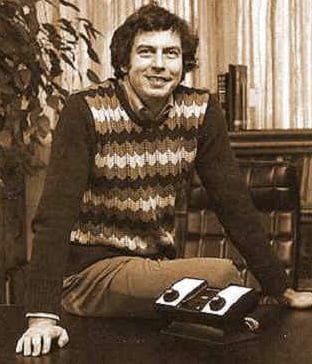

Alcorn with the first Pong in its original wooden box. Photo: Gavin Clarke

Back then, Alcorn didn't have access to these kinds of resources. Prefabricated off-the-shelf memory, processors and systems on a chip didn't really exist. If you were a start-up with vision in the early 1970s, you didn't just write the code or assemble the machine, you also built the basic components such as the chips from scratch as engineer Alcorn did. Designing the game play more often than not involved either copying the competition or jotting down some simple notes on a piece of paper.

When it came to bringing arcade Pong to the home, building the chips wasn't the biggest challenge facing Alcorn, a then recent graduate in electrical engineering and computer science from the University of California, Berkeley. In fact, it was building the game's rather simple exterior plastic casing that almost killed home Pong.

"The hardest part was the plastic case," Alcorn told The Reg during an interview at the Computer History Museum in Silicon Valley last year. "We had no idea how to make plastic tooling and consumer plastic products. I was so naive about it, it almost killed the project.

"I though the chip would be the hardest thing – how hard can the plastic case be? Well it turns out in those days it took four to six months to cut the metal that made the case and if there was a problem there was delay time. You lay a lot of money out and if it's wrong you can't fix it.

"All the other stuff on a chip is much easier to fix. And we [also] hired a contractor who was incompetent and a crook, and so I was three months into the project and I was like: 'Uh-oh, restart' so I had to scramble to get the thing out."

Home Pong couldn't have been more different to Alcorn's prototype arcade Pong machine. On the engineering side, Alcorn's speciality, it had 66 chips and a TV monitor that he had customised – plus a slot to take 25-cent coins for game play and two paddle controllers. Pong was stuffed into a rough, wooden box Alcorn made one weekend before and the prototype was dropped deep inside Silicon Valley at Andy Capp's Tavern in Sunnyvale, California.

Christmas crunch

Home Pong had its own digital chip and plugged into your existing home TV. And there would be no make-do-and-mend wooden casing for home Pong. Making matters worse for the home version was the pressure that came to bear on Alcorn as US retail giant Sears Roebuck & Co decided to feature Pong in its Christmas 1975 catalogue. Atari – the company formed by Bushnell to push Pong – was committed and there would be no backing out without serious loss of face and money.

Alcorn remembers: "They [Sears] usually shut the Christmas catalogue in March or April and they kept it open for us... the last time they did that was for a Marvin Glass slot car – the first slot car. They built 50,000 of them and the car could never get past the first turn and they had to buy all 50,000 back. Nolan and I are listening to this and thinking: 'If this happens to us, we're out of business. We're risking the whole business on this thing."

But Alcorn pulled it off and Sears sold nearly 150,000 home versions of Pong under the brand Tele-Games at $100 a pop during Christmas 1975. Such was the demand that people waited for up to two hours to simply to sign up to a waiting list for a home Pong. Home Pong is reputed to have become Sears' most successful product ever, earning Atari a Sears Quality Excellence Award.

Unintended success

Pong the home game had been in the frame from day one for Bushnell, but it was Pong the arcade game that started priming the demand three years earlier, in 1972. The arcade game, though, might also never have happened. Bushnell had hired Alcorn to build a better Odyssey after, legend has it, he attended a demonstration by Magnavox on 24 May, 1972. Bushnell founded Atari on June 27. Magnavox later sued Atari, along with others, for patent infringement.

The problem for Bushnell was he didn't have sufficient cash to invest in a home system in 1972; he had just $500, according to Alcorn, who became Atari vice president of R&D and after leaving Atari became an Apple fellow. "Doing a home game was way out of the question at that point in time for us. It cost too much money to make a chip. We didn't have any money," Alcorn told us.

Instead, Bushnell fell back on what he knew best: arcades. Bushnell had worked at an amusement arcade in Salt Lake City during his university years and had been inspired by Steve Russell's Spacewar!. Alcorn said: "He [Nolan] said: 'There's a game: if I can put that in an arcade where pin ball machines were, I could make a lot of money'."

Bushnell and Alcorn had met working at video and audio equipment manufacturer Ampex. Bushnell gave Alcorn, a recent graduate, the job of building Pong simply to get him up to speed on video game programming – a new field at that time. Bushnell, it seems, had underestimated just how driven Alcorn would be in delivering arcade Pong.

Nolan Bushnell: Arcade-turned-Atari man

"I got to work on it and that's the prototype I created in three months," Alcorn told us, gesturing towards the original machine, now sitting behind glass in the renovated Computer History Museum off the 101 freeway in Mountain View.

"I was disappointed because it had too many chips in it. Nobody told me it was going to be a throwaway. The real game was going to be a more complex game, but he [Bushnell] didn't tell me that. So I added speed up and sound and other features to it to make it playable. We put it in that cabinet over a weekend and put it in a bar [Andy Capp's Tavern in Sunnyvale]. It was a big hit.

"I was thinking: 'Who the hell would play this thing? It says Pong, there's a coin box on the side, there are no instructions and it requires two players.'"

As it happened, plenty of people wanted to play Pong, as Alcorn discovered when he got a call from the manager at Andy Capp's Tavern after just a single day – to say the machine had broken and that it needed fixing. When Alcorn arrived at the bar, he quickly discovered that the "problem" was the machine simply couldn't take any more money: the slot was overflowing with quarters. From that first machine to the last, Pong reputedly made four times as much money as other coin-operated games, with Atari selling more than 35,000 of the units.

Raunch-free

What accounted for Pong's early and unexpected popularity? Game play, yes, but also the casing of that humble and unassuming wooden box Alcorn had hurriedly assembled over the course of a weekend. There was a thriving business at the time in ornate fantasy art for arcade game casings. The understated design had helped pulled in a new group of gamers, one which is still in demand and which companies such as Nintendo and Microsoft have tried to lure with the Wii and Kinect: women.

Alcorn tell us: "We knew the game had to last for about a minute or two and Nolan wanted it to be a subdued cabinet. Back in those days the pin ball machine" – the staple of bars and amusement arcades immortalised by Elton John – "had lurid pictures of ladies and tits on them, and Nolan wanted [Pong] to go into bars and other locations that would appeal to women. I think this became a very good social game because women could play it because it wasn't biased sexually."

Atari quickly saturated its market, becoming as big as the dominant arcade games company of that time, Bally, giving Atari the money and motive to get into the home. Bushnell's company had a turnover of $40m in 1975 – with $3m profit. Also, clones were becoming an issue: Pong's architecture of 66 chips on a board programmed using discrete logic was easy to knock off. Soon, boards were coming from Chicoin, Meadows and Ramtek with even Bally offering its own Pong, called Pong Playtime.

Keeping it simple

When Atari entered the home-console market, it didn't just need something that gave consumers a TV tennis experience that beat the Odyssey, it had to also be hard to pirate. That meant concentrating almost all of arcade Pong's operations on a single, custom-made digital chip – one which also threw in the scoring and advanced sound missing in Odyssey.

"I wanted to do a custom chip that would make it hard for them to steal our stuff," Alcorn says. He worked with Atari colleagues Harold Lee and Bob Brown to deliver the magic. Alcorn reckons engineer Lee told him not to create a game that was too complex as it would defeat their ability to deliver.

"Harold Lee said: 'It [the chip] wouldn't work because your technology is evolving so fast. It takes a year to do a chip and that by the time it will be obsolete, but we can put your simplest game Pong on a chip'. And I though: 'Far out...' The three of us went of into a corner and put together a very crude but working chip. AMI did our prototype. We plugged it in and it worked."

In space, no one can hear you Pong: On-screen scoring and ball spin were advanced for the time

You can see the schematic of the design here.

That's when Atari called Sears. "We had no business plan. It was like a dog chasing a car. What do you do if you catch it? So we called Sears and Roebuck – we figured they are a retailer, and that's why the first Pong is from Sears."

History will record that Alcorn's chip actually failed to thwart the pirates, and home Pong was ripped off just as badly as arcade Pong. Home imitators sprang up, with – among others – Coleco's Telstar in 1976 and Nintendo's Color TV Game 6 in 1977, while General Instruments built and licensed a chip for manufacturers of similar ball-and-paddle games. It was probably a tribute to the simple brilliance of Pong that others wanted in on the action.

Today's gaming industry includes huge Japanese and US corporations and powerful design studios and labels pumping out installment after installment of the same game. Comparing the '70s gaming pioneers of the Wild West with today's giants, who will be gathering in San Francisco this week, Alcorn reckons he had it easier – even though he had to build everything from chip to casing. Back in the 1970s there was freedom to experiment and fail: Atari, for example, had flopped with Video Music before it hit paydirt with the successful 2600 VCS, which cemented the company name and allowed users to load different games into the console. This plugged your stereo into your TV to create a light show in tune with the music or, as Alcorn describes it, create "a hippie light show."

"We sold like zero [copies of Video Music]. It was no big deal, nobody was fired. If you can't make mistakes and fail you better not try to be too creative." Alcorn added: "It's much harder today; it's frightening as hell today. There's so much time and money in a game that you can't veer from it. If you're one guy: there it is, take it or leave it."

Is there a Pong equivalent today? Alcorn gives credit to Nintendo's Wii, the first of the wire-free and sensor-based controllers – which Microsoft has taken a step further with the Kinect. He says: "They [Nintendo] had the courage to do something new in a new class of games. I got disappointed with the Xbox and PlayStation in that you have basically have three or four types of games: there's the shooting game or the jumping game. And that's getting kind of boring. Things like Tetris appeal to me because that's only a game that exists in that medium."

What of the future of gaming? 3D is the next evolutionary step, Alcorn reckons, but the man himself isn't doing much to hasten 3D's arrival. Instead, he's been working in start-ups while in his spare time Alcorn only plays World of Warcraft, where he sees Apple co-founder and fellow Silicon-Valley chip-fiddler Steve Woz.

Simple, like a classic car

Compared to rich and complex titles such as World of Warcraft and Medal of Honor, or even compared to games as simple as Pac Man and Space Invaders for the Atari 2600 VCS, the game of Pong couldn't have been much simpler from the perspective of technology, design or game play. Yet all these titles owe their existence to Pong, which – like the Atari brand – continues to command a retro fascination.

As game-changers go, Pong was an unassuming contender. Perhaps that was its secret. "I'm just delighted people still admire something I did so long ago," Alcorn tell us. "Maybe it's the same thing antique cars have; it's a simplicity of the past.

"Imagine if somebody came out with a game that simple now. Even a simple game on the iPhone like Angry Birds, that's a lot of graphics. I mean on Pong, Nolan said: 'Make the ball round,' and I'm like: 'Screw you, I'm not making it round!'" ®