Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2012/02/03/the_uk_in_space/

Brit space agency sends up 1st satellite

Yes, this is news

Posted in Science, 3rd February 2012 10:19 GMT

So far, the UK space agency hasn't gone in for any of that headline-grabbing stuff like landing people on the Moon or launching Martian probes that get stranded in orbit before plummeting back to Earth – it leaves that sort of stuff to NASA and Roscosmos.

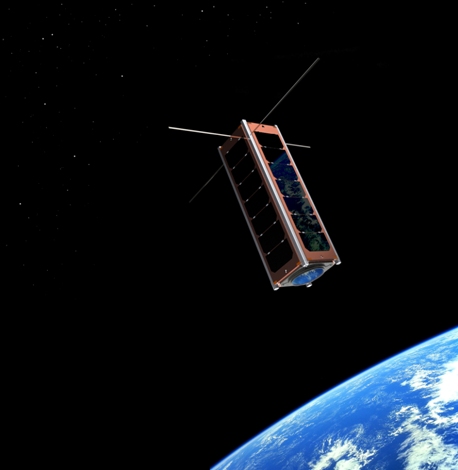

Willy Wonka's elevator Blighty's first-ever satellite...

The UKSA is usually just quietly involved in whatever the European Space Agency is up to, supplying parts and expertise to a variety of missions. (Apart from the International Space Agency, because the UK has elected not to get involved with manned space projects for now.)

As a result, there hasn't been too much to say about the body up to now. But that will change this year, with the launch of the first bit of genuinely UKSA kit into space.

UKube-1, a teeny-tiny satellite carrying a variety of scientific experiments, is due to launch later this year – providing it can find someone to hitch a lift from.

"We're still in discussions with potential launch providers for UKube-1, and are working hard to find a launch option for the satellite," head of communications Matt Goodman told The Register.

"Since cubesats tend to 'piggy-back' on larger payloads during a launch, finding an opportunity with the right orbital configuration is not straightforward."

This is a typical situation for modern space agencies, few of which seem to have the money to put their galactic ambitions into practice without a little help. And as the UK's agency isn't even a year old yet, it's not too surprising to find it in the same position.

But despite having to depend on other agencies for rockets, the UKSA is hoping that this year's UKube won't be the last.

"The idea of Cubesat is that we see it as a series with a launch every year or maybe two years allowing the sort of people that wouldn't normally get access to space to run experiments in it," David Williams, head of the agency, said.

"We'd like to see this being an ongoing programme because it gives university groups, and even school groups and amateur groups, the opportunity to test fly equipment. It also gives industry the opportunity to test fly and to develop ideas on bits and pieces of electronics."

The reason this is even a possibility is because Cubesats – a type of mini-satellite for space research – usually have a volume of one litre, a mass of around 1.3kg and typically use off-the-shelf components. In other words, they're cheap.

"It's tens of thousands, it's not a big number," Williams said of the cost of a single UKube.

Mini-satellites aren't exactly the sexiest space project going, but they are the first thing that the UKSA will be properly sending into space. And besides, the agency does have its hand in one really sexy space project: Skylon.

Skylon is an "unpiloted, reusable spaceplane intended to provide inexpensive and reliable access to space", according to the website of British firm Reaction Engines, which is hoping to build the new craft. (Read more about Skylon's techie bits here).

The project got the okay from the ESA in May last year, which said there was no reason why the design wouldn't work. Unlike UKubes though, Skylon has one major stumbling block: it'll be bloody expensive.

"We're trying to work with [the team] to work out how they can raise the necessary finance and whether government should have any involvement in it in the future," Williams said.

"It's going to be an expensive programme, several billion pounds over quite a long period, and the question is which industries wish to be involved, how UK should it be, how European should it be, should it be an international project?" he added. "The idea of a true single-stage-to-orbit plane is very novel."

If I were a rich man...

Money is also the reason why the UKSA isn't getting straight on the road to manned missions.

"In a perfect world, we'd love to do it, but of course we're not in a perfect world economically at the moment," Williams lamented.

But while there aren't billions to be handed over to the agency, it nevertheless is seeing funding from the government.

In November last year, the Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne promised half a billion pounds for science projects, including £21m to start another of the UKSA's satellite missions, NovaSar.

It's not anywhere near enough for a single satellite, but the agency already has backers in industry to make up the shortfall.

"The projected cost was £21m from the agency and about a £150m from other sources, ie, from industry, to complete the full satellite series, with an initial commitment for the first satellite on both sides. We think the first one will be in the order of about £45m all told," Williams said.

The object is to have a four-satellite constellation eventually, which will be put to all sorts of uses.

"At this stage, we have no specific plans, but we have a wide range going from marine surveillance right through to deforestation and polar monitoring," he said. "We intend to have an allocation of time pro rata to our contribution, which is about 15 per cent. So we'd expect to get time to allow the agency to work with scientists and departments across government to illustrate the value of the data sets."

Although this is a much larger satellite than the UKube will be, the agency is aiming to send it up by 2013, or 2014 at the latest.

In the next few years, UKSA will also be working on the ESA's ambitious Martian plans, the ExoMars project. ExoMars hopes to have an orbiter in place by 2016, followed by a rover for the surface in 2018.

"UKSA is heavily involved in that, we're the second largest contributor, we're looking at being the prime on the rover itself and on the Life Marker Chips*," Williams said.

And that's not the end of the UKSA's Martian ambitions.

"If that project pans out and moves forward, the next step is to be involved in a Mars sample return programme where you actually go to Mars, collect samples, and bring them back to Earth," the agency chief said, adding that he hoped the UK would be the place the samples returned to.

"It's a fairly major challenge, but you need these challenges in life," he laughed.

But again, it's all about international collaboration, because none of the agencies could bear the cost of the project alone.

"The aim was to be ESA and NASA, whether NASA will stay with us is open to question," Williams said. "But it will be a major programme and by the time it gets off the ground it will probably almost be global, almost like the Space Station – a combined effort."

Most of the agency's partnerships so far have been with Europe, and by extension NASA, but Williams said UKSA was also in talks with Roscosmos and the Chinese Space Agency.

"It's a changing world in space with countries maturing and some countries wanting to move in. And it's not just about science any more so we have to start working with countries on a bilateral basis as well as on a collective basis," he said.

Science is one of the reasons the UK wants its own space agency, but it's the bits that aren't about science that are really driving investment.

"The world at large uses space completely now in everyday life. Not only broadcast communications and satellite TV, but a lot in the background of how people work - the use of GPS, etc, all involve space," Williams said.

"Nearly everything the MoD does has a space component somewhere so you've got to be at the very least an intelligent customer, you need to understand the technologies. We've decided we want to maintain our technology capabilities so the agency gives that focus." ®

Bootnote

*The Life Marker Chips are a science experiment intended to analyse Mars' chemical make-up to try to answer THE question about the Red Planet: whether it has the conditions for life.