Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/12/24/2011_review/

Reg review of 2011: Jobs, floaters and 90,000 tons of radioactive water

Cue commentards going nuclear ...

Posted in On-Prem, 24th December 2011 12:02 GMT

Part One... Time-travelling neutrinos, lost Russian space probes, and a nuclear meltdown in Japan proved the worlds of physics, space and nature remain untamed for our brave boffins. In tech, meanwhile, Hewlett-Packard melted down, Steve Jobs died and his company's iPad proved untouchable in leaving PC makers lumbered with millions of dollars of unsold tablets.

Re-live 2011 with The Reg here...

From IPO spring to Wall St Winter

In Silicon Valley, 2011 was the year of the IPO. The pace of tech companies - specifically social networking sites - going public was unmatched since the dot-com days at the beginning of the last decade. The new crop claimed their road to investor returns lay in monetising large audiences of people who want to share online or who want bargains.

Wall St welcomed social network IPOs, then caught chills

LinkedIn led the way in May followed by Pandora, Groupon and Angie's List while Yelp and Zynga filed for IPOs. Facebook is expected to float next year.

However, what had started amid great promise had developed a distinctly chilly feel by November. Groupon's IPO was the biggest for a web company after Google, raising $700m, but soon after, investors were expressing concerns about possible competition to the daily-deals coupon-monger from Google and Amazon, and the fact Groupon must spent continuously to grow.

Groupon has now been forced to restate its earnings, cutting its 2010 sales number in half to $312.9m. 2011 revenue was also cut in half. Groupon stock has taken a pounding - going $11 below their opening price of $26.

Not helping is Groupon's funny reporting, employing something it has called "adjusted consolidated segment operating income", which the company said it is using because "we don't measure ourselves in conventional ways". Following criticism, Groupon's business heads decided to revise this metric slightly.

Zynga, the social networking games pin-up popular across TechCrunch-types, has also filed for IPO. However, the closer Zynga has drawn to its IPO, the more the lustre that had dazzled so many has started to wear off. Profits have fallen 90 per cent and growth in new users is more or less flat. If social networks need one thing more than new ways to milk money from existing users, it's new people signing up.

Now, Zynga's hard-work culture that was hailed when things were rosy was counting against it. Zynga always was a tough place to work, it's just that Silicon Valley overlooked the fact.

It remains to be seen whether the Valley's taste for IPO, rediscovered in 2011, will endure next year – given the hit on Groupon and Zynga's wobbles. For Wall St's investors to warm again to the Valley's IPO hopefuls in 2012, they will want to see some standard business reporting put in place along with solid projections of attainable growth - not flat numbers.

Facebook v Google: the battle over who owns your data (and it isn't you)

The year marked a watershed for Facebook in its ascendency and rivalry with Google. Facebook was held down on privacy while Facebook and Google deployed the tanks against each other. The prize was simple: to be able claim your data and know more about you, so both companies could profit.

The year saw Mark Zuckerberg and his company became the go-to hangout buddy for US politicians from President Obama to New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg and Senator Chuck Schumer. Power and popularity attracts politicians, and with 800 million users and a possible IPO value of $100bn, Facebook has the kind of pull politicians feel they can't afford to ignore.

Not a turkey: Zuckerberg's privacy policy finally got serious

The political love accompanied some PR warm-and-fuzzies for the industry and the media. The company generated excitement and positive coverage when it "open-sourced" the specifications and design documents for the custom-built servers and racks used in its new Prineville, Oregon data centre in April. Zuckerberg, meanwhile, was made available for a BBC documentary on the making of Facebook, and a Wired cover article.

Behind this respectability, though, was a large and unresolved problem, a problem that struck at the heart of Facebook's desire to make money out of its 800 million members. The problem was privacy.

Since Beacon in 2007, Facebook has been looking for ways to expose its users' data in exchange for money from advertisers... and it has been pulled up and kicked back each time. In 2011, however, the US government's regulators finally called time on the on-going efforts. Following an investigation by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Facebook agreed to a bi-annual privacy review for the next 20 years. The FTC ruled that Facebook was "unfair and deceptive, and violated federal law" on privacy.

Zuckerberg issued a mea culpa on his Facebook blog while also creating two Chief Privacy Officers positions to supervise Facebook policy and products. With a 2012 IPO in the air, and the courtship of media and politicians in motion, Facebook had to be seen to be doing the responsible thing - even if the wording of Zuckerberg's apology indicated he didn't really believe Facebook had done much wrong.

2011 also saw skirmishes between Zuckerberg's company and search giant Google escalate as both tried to monetise their millions of users and ensure growth. Not content to pinch each others' execs – helping drive up Bay-Area wage inflation for tech companies – the pair also sniped at each other and set out their defences around their users' data.

Google launched Google+, a Facebook-like sharing and status-update service the Mountain-View company is tying into its ads network. Before that, Google introduced a knock-off of the Facebook "Like" button with +1. Facebook applications were also barred from using Google's AdSense while Google stopped the ability for Facebook servers to hover up the gold-dust Gmail contacts info.

The field is set for 2012. As a public company, Facebook was always going to be more open to scrutiny over privacy then ever before. Now, it has the added humiliation and inconvenience of an FTC hawk on its shoulder. The regulatory restrictions on Facebook come as the company tries to look for new and even more inventive ways not just to grow, to satisfy potential shareholders, but to also beat Google.

Death of Steve Jobs

Google, meanwhile, is trying to become more responsive and nimble – against the background of a quick-moving Facebook – by returning to the start-up culture of the early days under co-founder and re-appointed CEO Larry Page. As part of that process, Eric Schmidt was moved aside as CEO after 10 years at the top while a number of projects have been killed, and search and Gmail have been changing. The giant will look for ways to turn its search customers into permanent residents of a Google community.

2012 promises to be an even more bruising experience in the history of the two companies' relationship.

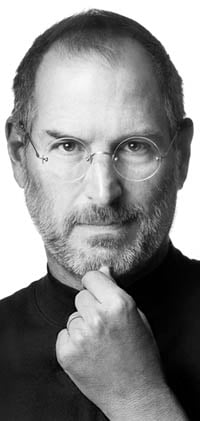

Creative, businessman, tough-guy, geek? Death of Steve Jobs leaves a riddle

Steve Jobs passed away in October at the age of 56, following a long-running battle against a rare form of pancreatic cancer going back to at least 2004.

The canonisation was instantaneous: Barack Obama, David Cameron, Stephen Fry and ordinary Apple customers were among those flocking to quickly pay tribute. They repeated the same phrases and sentiments: a creative genius, a visionary, an inspiration, a man who changed the way we live and work. Messages were left online and outside Apple's stores.

The praise came easy, but who was Jobs really?

Who was this CEO of a relatively small company in the tech sector whose passing even national leaders felt obliged to acknowledge?

The history is known. Jobs co-founded Apple with geek friend Steve Woz in 1976 where they created an accessible form of desktop-based computing based on the Graphical User Interface (GUI). For his pains, Jobs was kicked out some years later by a political company board and the CEO he hired. Jobs then founded and ran NeXT, invested in Pixar, was welcomed back to Apple, then delivered the iMac, the iPod, iTunes, iPhone and iPad.

The Mac continues to ship well and hold up a solid six-to-seven-per cent market share against the overwhelming number one, Windows. The iPod, iPhone and iPad in a short time managed to command compelling sales and market share - more than 70 per cent market share for Apple's music player, a quarter of US smartphone sales in just a few years for the iPad, and an anticipated 13.5 million units for the iPad 2 this quarter.

Microsoft for all its success actually owes Jobs and Apple a debt of gratitude: it was Microsoft's word processing and spreadsheet apps running on the Mac that made the apps look so beautiful and easy-to-use and that helped to sell the idea of the GUI on a PC. This laid the ground for the PC revolution, pushing Office and Windows to their number-one positions.

The competition - companies like Microsoft - continued to underestimate Apple and Jobs. Four years after the iPhone and nearly two years after the iPad was introduced, Microsoft - the world's largest software company and king of the PC - is still scrambling to catch up. Google, the world's largest web search company, cooked up Android against the iPhone.

Jobs wasn't defined by being "just" a technologist, some soft-faced seer of the future who let others benefit from his wisdom. Jobs was an aggressive competitor and even with a liver transplant behind him, Jobs was driven enough to unleash his lawyers on the smart-phone competition on the subject of patents, resulting in a Reservoir Dogs-style patent shootout.

Since 2010, Jobs waged an intense one-man jihad against Adobe and its Flash Player to the point where Adobe has now given up on Flash for mobile. Flash dates back to 1993 and became the go-to-way for building and running video, graphics or ads on PCs and online through a browser plug-in.

Adobe claimed more than 90 per cent of web-connected PCs were installed with Flash but Jobs wasn't letting Flash on to either the iPhone or the iPad. He called Adobe's software buggy and backward, and he championed HTML5 instead.

Was he being genuine in his embrace of HTML5 or was he fogging the issue to keep the iPhone and iPad open only to Apple? It didn't matter, because by November 2011 Adobe said it was stopping development of Flash for mobile and handing over its Flash-based Flex SDK to an open-source foundation.

Since 2010 Jobs waged an intense one-man jihad against Adobe and its Flash Player to the point where Adobe has now given up on Flash for mobile.

It was sad that for all his foresight and fire on technology, Jobs couldn't see into his own future. According to the biographer of Apple's CEO, Jobs held out against potentially life-saving surgery for too long, and picked alternative treatments instead. It was a decision he regretted.

For all the kind words, there were also words that hinted at the darker side of Jobs' competitive actions and driven personality. A year before Jobs passed, Apple was singled out by web daddy Tim Berners-Lee for helping kill the open web by locking up data inside an iTunes walled garden. Open-source firebrands Richard Stallman and Eric Raymond unleashed three bad taste attacks on the Jobs legacy: Stallman reckoned Jobs exerted a "malign influence" on computing, while Stallman said Jobs had hypnotised millions "into a perverse love for the walled garden." Others took issue with the consumerism – the i-everything.

Those close to him have revealed how just how much the "brilliant" Jobs actually relied on the genius of other people at the critical times in his career. They also revealed how he's failed to acknowledge the parts they'd played. The engineering brains behind the first Apple machines was Woz. He made Woz cry, having tricked his friend and business partner in a game development deal with Atari that saw Woz do the work and Jobs pocket the bonus. More recently, it was gentle-faced Jonathan Ive – lead designer on the iMac, iPod, iPhone and iPad – who had cause to complain. In his biography, Ive says he and others became upset at Jobs because Jobs had taken too much of the credit for their ideas.

A Jobsian riddle answered?

In the final analysis, Jobs took existing ideas and refined them: the GUI was already in existence at Xerox PARC, MP3 music players pre-dated the iPad, and it was Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates who was the first to really talk tablets.

Apple's CEO was a tough act: as driven inside as he was outside of Apple. He often saw a way to make existing things and other people's ideas better. With his closed systems and ecosystems, Jobs was no worse than any other tech CEO trying to make money and keep making money for his company. The ethics you can debate.

You just need to keep some perspective.

Loss-makers of the world unite: MS buys Skype, Google buys Motorola

The Skype and the Motorola deals were record-breakers for Microsoft and Google: $8.5bn and $12.5bn – the most either had paid in for anything.

The deals were groundbreaking in other ways, too.

Skype potentially turned the world's largest software-maker into a web telco – also the dream of Skype's previous owner, eBay. Such was Microsoft's belief in the promise of Skype that CEO Steve Ballmer broke Microsoft's M&A rules: the internet phone service would be run as a separate division under its CEO Tony Bates, who reports only to Ballmer. It would not be folded into an existing Microsoft product group under another president.

Ballmer and Bates announce Microsoft's move into web telecoms

For Google, the purchase of Motorola Mobility meant the world's largest web search provider had become a manufacturer of handsets. Google had dabbled in handsets with the first Nexus from HTC, but these were pulled as Google's Android handset partners didn't like the idea of competing against Google.

On the Skype acquisition, Microsoft's Ballmer spun it like this: "Together we will create the future of real-time communications so people can easily stay connected to family, friends, clients and colleagues anywhere in the world." As for Google, the company told the world that Motorola wasn't about handsets, rather it was all about patents - taking ownership of phone patents to shore up Android against the lawyers from Oracle, Apple and others.

With both deals, though, it seemed Microsoft and Google had been "had". Microsoft took off of eBay's hands a loss-making VoIP phone service with no prospect of making money under Bates. It had paid over the odds – $8.5bn instead of a mere $7bn that was being asked – to a circle of rich Silicon Valley VCs who had bought into Skype with the express aim of unloading it on to somebody else. There was no bidding war to drive up the price, either, because nobody else had been interested in buying Skype.

The VCs, who included Microsoft's one-time browser nemesis Marc Andreessen, made $6.6bn in cash – not Microsoft stock.

Ballmer and Bates appearing at joint press conference in May to announce the deal talked a lot about "optimising" and developing Skype for Microsoft's Xbox, Kinect, Outlook, Hotmail, and Lync real-time-communications server. This seemed to suggest Skyping inside Xbox or Hotmail, which was conceptually the same fluffy voice-meets-community thinking that had seen eBay buy Skype. There is the potential of Skype for business communications but Microsoft will need to invest a lot to improve Skype's QoS and do so without upsetting its carrier partners.

The best on the table is that Silicon Valley social networking myth of selling more ads. Was that worth $8.5bn? Likely not, and like so many other corporate mega deals that came with equally grand-yet-vague promises, it's likely not to move the needle on revenue or market share for the main business.

Microsoft's last big deal was the diversified ads and media shop aQuantive in 2007 for $6bn. At the time, Redmond said it would take Microsoft to the "next level" in online ads. It didn't, and after many staff exits and after being turned into Microsoft's advertising arm, Microsoft's online ads still make fraction of the money Google rakes in.

Page play: Larry's Motorola buy a bust?

In the Google deal, Motorola's management, too, managed to unload a loss maker with shrinking market share at a handsome price. And, while Google's boss Larry Page talked patents, the kinds of radio and design patents that old-school telecoms manufacturers like Motorola own are outdated in the touch-screen world of smartphones and are irrelevant in the current game among handset makers of standing in a big circle and shooting at each other to see who makes it out alive. It's extremely unlikely that what Motorola owns will help see off Oracle, the database giant which alleges Android infringes its Java copyrights, given Android's Java component originates from an Apache Software Foundation (ASF) project.

As 2011 closed, it looked like Google spent $12.5bn on a poker chip that was a dud. Microsoft had become the proud owner of somebody else's dream.

Microsoft to put Windows on ARM

It's not you, it's ARM: Microsoft, Windows 8 and the tablet play that broke Wintel

Intel and Microsoft were the Liz Taylor and Richard Burton of 1990s computing: a mighty power couple whose union exuded power and left the meek humbled.

Such was their success that competitors and regulators would cry foul and seek remedy through the courts at different points in their histories.

As a pair, from humble beginnings at the dawn of the PC revolution, they became responsible for the more then 300 million PCs that are sold around the globe each year.

At the start of 2011, the 32-year marriage ended in the only way such bright-burning do-no-wrong relationships can: cheating followed by public allegations and flameouts.

Intel's Otellini: Windows on ARM is nothing

The third party responsible for getting between these two West Coast corporate giants was the humble British system-on-a-chip architect ARM. The person who responsible for their hooking up? Steve Jobs. The venue? The place responsible for many a guilty act: Las Vegas.

Back in January, Microsoft's chief executive filled his familiar keynote slot at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES), with a standard sales pitch that tried to - unconvincingly - sell Windows as a player in tablets. Only Ballmer called them "slates". Ballmer demoed a trio of devices running Windows 7 that have since been pretty much unheard of.

It was away from the spotlight, however, in a small CES side room, where Microsoft quietly delivered the real news. It told a handful of carefully picked journalists that the next version of Windows - Windows 8, already in development - would run on SoC ARM architectures from NVIDIA, Qualcomm, and Texas Instruments in addition to Intel and AMD x86. Windows 8 would, therefore, become the first version of Microsoft's multi-billion-dollar-a-year PC client operating system to run natively on ARM.

Intel might dominate the PC, but the PC market is suffering a crisis of direction in the face of a mobile tsunami accelerated by the iPhone and iPad.

And while Intel is working to squeeze into mobile with Atom, ARM is already in mobile. Its ARM's Cortex-A8 CPU is used in Apple's A4 chip with a PowerVR GPU on the iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch to make these devices more power efficient; ARM supplies chip designs to 95 per cent of the world's smartphone market; ARM has about 10 per cent of the mobile computing market today but reckons it can hit more than half by 2015.

The first reaction from Intel was diplomatic. Speaking to press also at CES, Intel CEO Paul Ottelini said Windows on ARM wasn't news, yet he still welcomed the development and went on to claim that Intel's vast size and experience meant it would win.

Four months later, on 18 May, Intel was being less diplomatic and telling the world that existing Windows apps wouldn't run on the ARM fondleslabs.

This was something the man at Microsoft driving Windows 8, Steven Sinofsky, had actually put out there as a distinct possibility, so the statement by Intel was an important development. Who was telling the truth? Intel continued "Windows 8 traditional" would offer a "Window 7 mode" and said there would be four versions of Windows 8 for each of the four SoCs ARM makers picked. The comments were made by Intel's software chief Renée James.

Microsoft loses control

Desperate to control the message and exercise some form of damage limitation, Microsoft shot back at Intel on 19 May, going so far as to actually issue a statement to shoot down the claims rather take the standard route of not "commenting on rumors and speculation".

Microsoft said James' comments were "factually inaccurate and unfortunately misleading" but it refused to provide more details. Maybe, but by the end of 2011, one thing James said seemed to be coming true: Windows apps on the new ARM devices wasn't going to happen. That'll be a major set back for Microsoft and the ARM relationship, in terms of getting x86 PC customers who want the same apps they get on the desktop on their ARM tablet too.

Microsoft has had a long and beneficial relationship with Intel. The chip giant came along at just the right time for Microsoft in the 1980s. IBM had teamed with Microsoft on MS-DOS on the IBM PC 1981 but by the end of the decade IBM had decided that it wanted to push OS/2.

Saved by circumstance

Microsoft had different ideas, so Windows 2.0 in 1987 was designed to work with Intel's 286 processor. Two years later Intel released the 486, described by Business Week as a "veritable mainframe on a chip" while the 1990s became the era of Intel's Pentium chip. Intel's liberated Microsoft from IBM and gave Microsoft's software the power and responsiveness to succeed in the PC revolution of the 1980s and 1990s.

While the pair are today behind most of the 346 million PCs sold each year globally their efforts are dwarfed by what's been happening in mobile computing. Smartphones have been selling in the billions-of-units range for years and are expected to hit a record 1.55 billion in 2011. Apple – which accounted for around 75 per cent of tablet sales last year – is expected to move 20 million iPads this quarter.

Some are saying the era of the era of the laptop is now over. Maybe, but one thing that certainly did come to an end in 2011 was the Wintel alliance.

Would Leo Apotheker please turn the lights out on his way out of HP?

2011 was remarkable for Hewlett-Packard, the world's number-one maker of PCs, because it slammed the door shut on the madness that started in 2010.

In April 2010, former CEO Mark Hurd bought Palm, the widely liked but strategically mishandled maker of devices and the webOS operating system, for an eye-popping $1.2bn. In September the same year, Hurd was gone for other reasons and HP in November dipped hired a CEO who never stopped telling everybody he was a "software guy" so knew the biz. He was the ex-SAP CEO, Leo Apotheker.

HP's Mr Software, Leo Apotheker, was gone in a year

Fresh into the job in March, Apotheker made his mark: in 2012 every HP PC shipping with Microsoft's Windows will also ship with the Linux-based webOS as well, he said. "You create a massive platform," Apotheker predicted.

Ten months after Apotheker became CEO he was out, replaced by ex-eBay CEO and one-time California Republican-party gubernatorial candidate Meg Whitman. WebOS was also gone, putting an end to HP's webOS tablet and any plans for webOS also on PCs running Windows as their primary operating system.

The end of both webOS and Apotheker looked like the end of a bet by HP board that "software" could lift their company above the funk infecting the PC market and mindset.

And what a funk: PC shipments in 2011 are expected to grow just 4.2 per cent this year compared to 13 per cent in 2010 according to IDC, which had predicted 7.1 per cent in February.

The only question is whether the funk is caused by the rotten economy and the end of consumer interest in the netbook or whether there is a tectonic shift in motion, such as a permanent move to smartphones and tablets.

Certainly, 2011 saw HP attempt to ride the mobile wave, with the TouchPad. The company was proud: possibly too proud.

"In the tablet world we're going to become better than number one. We call it number one plus," said HP's EMEA personal systems group said in May. The TouchPad launched in July but it was clear from the start that this was no iPad: 12,000 sold in the first month of availability compared to one million for the iPad a year earlier. By the end of August, retail giant BestBuy had shifted less than one-tenth of its 270,000 inventory. Cruelly, HP's decision to kill the TouchPad in August boosted sales.

HP wasn't unique in its suffering. Dell, Samsung, Motorola and Research in Motion all confidently took to the field against the iPad and all cut prices. In the largest act of PC-related carnage since Windows Vista, OEMs have lost billions in channel discounting, development, manufacturing and marketing.

"HP wasn't unique in its suffering. Dell, Samsung, Motorola and Research in Motion all confidently took to the field against the iPad and all cut prices."

Unlike its peers, however, HP went further than corrective surgery in a struggling product group: a month before he went, Apotheker announced a major operation. He confidently told Bloomberg that HP was weighing the sale of its PC group. This was no IBM spinning off PCs to the Chinese and transitioning to servers, services and software, this was the removal of a healthy organ critical to HP's business. PCs had showed year-on-year as well as sequential quarterly growth for operating margins in August.

The filler for PCs? Software: HP bought a search software company called Autonomy, a UK technology success less well known in the US, for $11bn.

However, time ran out for Apotheker in September and Whitman became the new chief. According to a statement with non-executive chairman Ray Lane's name on it, the HP board was "fully focused on doing what's right for HP and the future of this iconic company... The decision to change the leadership of HP is one the board took very seriously."

No more PC spin-outs

Compare that to the year before, when Apotheker was hailed by board member Robert Ryan as a "strategic thinker with a passion for technology, wide-reaching global experience and proven operational discipline - exactly what we were looking for in a CEO. After more than two decades in the industry," Ryan added, "he has a strong track record of driving technological innovation, building customer relationships and developing world-class teams."

Nixing the PC spin-out was one of Whitman's first acts.

Whitman's reign ended a turbulent year under Apotheker. Her appointment seemed to indicate that those running the world's largest PC company had given up on the idea that an ideologist - a software ideologist in this case - could put HP on new course. In Whitman, HP had picked a business operator - a technocrat - who, as eBay's CEO, had ran a company that was a technology consumer and that used software, services and data centers to grow the business. She wasn't known for prescribing a bold directions or for being Ms Software.

Hopefully, for HPs sake, this will mean evolution into the kind of post-PC future Apotheker thought he could force.

There are challenges. HP's cloud has yet to materialise, despite much hot air and talk of OpenStack. HP's tablets will run Windows 8 not webOS; while that means HP's tablets should have the familiarity of Windows on the PC and reflect the kind of steady-as-she-goes comfortable thinking HP wanted, there's no guarantee that Windows 8 tables can do any better against the iPad than the webOS-powered TouchPad. No matter what happens to these new ideas, though, at least HP will have the PC business to help keep things ticking over.

Fukushima crisis: from nature, a mighty wave

In 2011, the most powerful earthquake in history resulted in the biggest catastrophe to hit Japan since the second world war.

The quake, a magnitude 8.9, struck off the northeast coast of Japan on March 11 and was so powerful it knocked the planet several feet off of its axis.

It also unleashed a fearsome tsunami wave. Traveling as fast as a jet airliner, the wave hit Japan's coast, wiping out entire towns and villages: officially, 19,000 people were killed by the quake and wave.

The tsunami also triggered one of the most serious civil nuclear accidents in history, when it struck the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant on Japan's northeast coast.

The plant managed to survive the quake but the tsunami shut down the plant's back-up generators responsible for cooling four nuclear generators. A following combination of explosions and meltdown resulted in the release of radioactive caesium and iodine into the atmosphere.

Around 160,000 residents were ordered out of their homes in the 20km area around Fukushima and an exclusion zone established. The Japanese government now reckons it will be 20 years before residents can return.

During the darkest hours of the crisis, when there seemed no containment in sight, there were scares over contamination of milk and water, of radioactivity hitting the atmosphere and of running into the waters of the Pacific Ocean. It didn't help that a US carrier that happened to be the region, the USS Ronald Reagan, was pulled back as a precautionary step.

The media reporting didn't take down levels of tension, as comparisons with the Chernobyl explosion and meltdown in 1986 were quickly, and inevitably, drawn.

Explosions and meltdown at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear plant

The hospitalisation of two plant workers for exposure to "higher-than-normal" radiation rates was a gift to a media gripped by nuke fear. In fact, the pair took a shot of around 170 millisieverts to the skin on their legs. The accepted value is for 100 mSv in an emergency, although the World Health Organization's limit is 500 mSv. In Chernobyl, about 134 plant workers and firefighters received does of 800 to 16,000 mSv and suffered acute radiation sickness as a result; of these, 28 died within the first three months from their injuries.

While Chernobyl and Fukushima both received International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Level 7 severity ratings, Fukushima saw less radiation released than Chernobyl; also, there were no casualties attributed to radiation compared to 64 at Chernobyl.

Nine months later, the authorities have achieved a state of "cold shut-down" with the reactor's fuel having cooled to a temperature where there's no nuclear reaction, while little radiation is being released into the atmosphere.

Japan's authorities must now work out how to physically contain the damaged reactors, with a Chernobyl-style sarcophagus. The prospect of people returning to the exclusion zone is a generation away as radiation readings in the zone are as high as 200 mSv per year – the maximum dose allowed for a worked in the US nuclear industry is 50 mSv per year and a US civilian is 6.2 mSv per year from natural and man-made radiation sources. The real problem is the presence of caesium 137, which digs into soil, and finds its way into the food chain. This has a half life of 30 years.

Meanwhile, there's the small problem of what to do with 90,000 tons of radioactive water that was dumped on the heating cores at the height of the crisis and that is now sitting in huge containment vessels. ®

The roundup was too large to squeeze into one article. Look out for part 2 over the next few days, giving you a much-needed distraction from the Christmas family frenzy. Don't say we never do anything for you.