Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/12/06/merging_tsunami_japan_nasa/

Boffins: Japan was hit by 'double-wave' tsunami

Two became one

Posted in Science, 6th December 2011 10:22 GMT

Boffins from NASA and Ohio State University have discovered that the tsunami that hit Japan in March 2011 was a so-called ‘merging tsunami’.

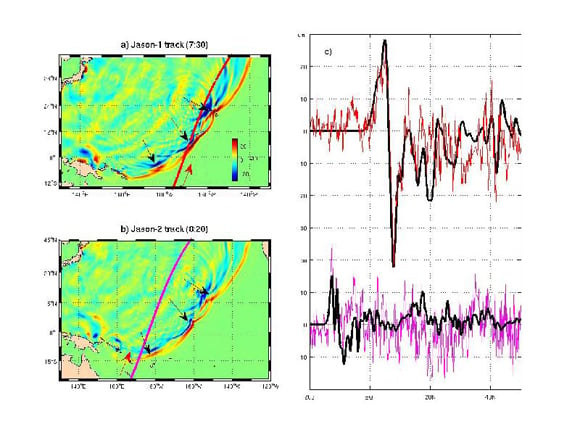

Merging tsunami data from two satellites. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Ohio State University (click to enlarge)

The idea of a merging tsunami, where two or more wave fronts join to form a single wave capable of travelling long distances, has long been hypothesised, but never before confirmed.

NASA and European radar satellites captured at least two wave fronts on the day of the Japanese tsunami, which merged to form a single double-high wave far out at sea that could travel to the coast without losing power.

The two fronts were pushed together by ocean ridges and undersea mountain chains near the tsunami’s origin.

The data gathered could help scientists to improve tsunami forecasts.

"It was a one in 10 million chance that we were able to observe this double wave with satellites," principal investigator Y Tony Song said.

"Researchers have suspected for decades that such 'merging tsunamis' might have been responsible for the 1960 Chilean tsunami that killed about 200 people in Japan and Hawaii, but nobody had definitively observed a merging tsunami until now," he added.

"It was like looking for a ghost. A NASA-French Space Agency satellite altimeter happened to be in the right place at the right time to capture the double wave and verify its existence."

The trouble with tsunami forecasts now is that while the underwater earthquake that is the origin of the event can be pinpointed, the waves themselves often seem to go off in random directions, causing massive destruction in some places but leaving nearby areas unharmed.

The researchers think that ridges and underwater mountains can deflect parts of the initial tsunami wave to form a number of wave fronts.

Current hazard maps that try to predict where tsunamis will hit only take into consideration sea-floor topography near shorelines, but this research suggests scientists might be able to create maps that also take into account ridges and mountains far from shore.

"Tools based on this research could help officials forecast the potential for tsunami jets to merge," Song said. "This, in turn, could lead to more accurate coastal tsunami hazard maps to protect communities and critical infrastructure." ®