Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/11/28/javafx_2_point_0_part_three/

Time up for Oracle's HTML5 killer?

Message to Ellison: no more JavaFX reboots

Posted in Software, 28th November 2011 15:00 GMT

Open-source Java: Part Three Sun Microsystems in 2007 announced a re-imagining of GUI platform Swing with JavaFX. Swing, Sun said, had reached an architectural dead-end and need a reboot to compete on modern, Rich Internet Application (RIA) platforms.

As Sun pitched JavaFX, Adobe brought out Flex (which is based on its Flash Player plug-in) and Microsoft countered with Silverlight.

It's unfortunate that just as JavaFX 2.0 is being released, those who helped inspire it are going HTML5. Meanwhile, almost nobody uses the phrase "RIA" anymore.

Microsoft has all but sidelined Silverlight while the bell of uncertainty is tolling for Flex with Adobe's recent announcement that it is floating the Flex SDK out to the community. Adobe insists it is still behind the Flex SDK, but it seems more like a loving form of euthanasia. Adobe, meanwhile, has decided to stop development of Flash Player for mobile.

The culprit in both cases is HTML5, the next version of the web mark-up protocol that is killing closed and proprietary media stacks.

Is JavaFX - the subject of our third and final look at Java five years after Sun released it under a GPL licence - in the wrong place at the wrong time? Has it already lost and doesn't know it? Maybe not: Microsoft may have had Windows to leverage Silverlight but Adobe was the real leader thanks the the dominance of Flash and Adobe's surprise change of direction could make way for new, standards-based development tools - if Oracle can get serious on JavaFX. Delivering on its promise to open-source JavaFX might also help.

What does JavaFX have going for it? Keep a close eye on Edge, a "web motion and interaction tool" that uses HTML5, CSS3 and JavaScript. Preview 3 is already available. The key word in Adobe's description is "tool", and it's something that Oracle's JavaFX team appears to have misunderstood from day one.

With Adobe it's all about the tools: the platform is almost secondary, it just needs to be sufficiently kickass to support the designer-oriented toolset.

When it comes to Oracle and Java, however, the platform's the thing and tools are demonstrably an afterthought, as the database giant has shown with their continued lack of a JavaFX GUI editor.

Like a Quake Live match where all the players have dropped out leaving just one player to run silently around an empty map, Oracle may suddenly have the RIA arena all to itself. But is JavaFX good enough to capture the flag with no opposition, or will it manage to frag itself instead?

After the disaster that was JavaFX 1.0, Oracle has a lot to prove. Nevertheless, four years and another incompatible redesign later, we have version 2.0.

Time to 'fess up

While there's much that is good about this latest "'fess up to the mess up" reboot, JavaFX 2.0 is mostly defined by what's missing - a theme that also ran through the keynotes at Oracle's annual JavaOne this year. It's very revealing of the mindset involved that on the official website, the "What's New?" link actually points to the JavaFX Roadmap.

But let's start by looking at what the troubled GUI platform does have to offer.

JavaFX has three deployment models: Desktop, Applet and JNLP (WebStart). It also supports a "preloader app", which is run before the main app loads. For example, you could do things like provide a custom animated loading screen, pre-load options or run a security check. The Application class provides a convenient hook into the enclosing web page or other host service.

Changing times, terrible tools

Central to the new architecture is the Scene Graph, which is comparable to the browser DOM; even to the extent that CSS styles can be used to apply styles and layout rules. In fact CSS support is a particular strength in this new release.

There's a set of modern new components that look pleasing in their default configuration, so you won't sweat to make your app not look horrible (a criticism that was commonly levelled against earlier versions of Swing). Naturally, the components look nothing like the underlying OS, but then nothing does these days (least of all the OS itself, paradoxically), so that's really not a problem.

Also new is a browser component that renders HTML using WebKit - a welcome addition.

The oddball JavaFXScript, which had all the grace of a drunken gazelle in JavaFX 1.0, has been dropped in favour of pure Java combined with a Flex-alike declarative "layouting" language, FXML. The idea is to split the UI definition from the behaviour, and to make GUI tooling support easier.

FXML is a first step in the right direction, but it has a long journey ahead. Community developers are stepping up to supply the missing pieces such as Dependency Injection (DI), which will make unit testing far easier, but this stuff should be there out of the box. Same goes for linking the spanky new components up with data sources. Oracle can thank their lucky stars for a patient and enthusiastic community.

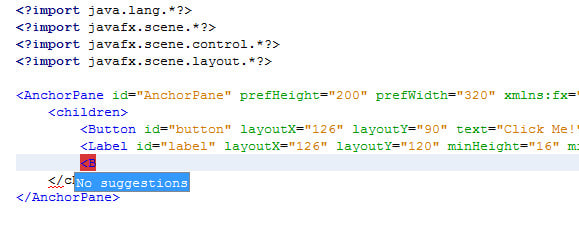

No help: Code completion in NetBeans' FXML editor

The examples - a separate download from the main SDK - are kind of nice, but are not on par with Adobe's Tour De Flex, and font rendering is rough. Bizarrely, given the amount of noise behind the new FXML, the source for the examples is almost all in Java: very little FXML to be seen.

Initially, Oracle is only supporting the latest beta of old-men's-club IDE, NetBeans. Oracle's strange infatuation with NetBeans at the expense of Eclipse and IntelliJ might hinder JavaFX's adoption.

The decision appears even odder when you consider that Composer, NetBeans' visual GUI designer, is taking an extended pit-stop while it's being rewritten. This means we're back in the surreal position of having Java's premiere GUI platform without a GUI editor.

It's a clear sign that Oracle still doesn't get that application development is all about providing quality tools, much less about the platform. The editor can't be an afterthought: it has to be the centre of their universe, with all development efforts spreading out from it.

JavaFX programs can still be developed in your IDE of choice: just link in the external jfxrt.jar like any other library. But you just won't get the linked-up editor support that you'd reasonably expect. For a more integrated experience, do check out Austrian developer Tom Schindl's flowering Eclipse plug-in, e(fx)clipse (although if I'm honest, Schindl's proprietary DSL, FXGraph, may limit its appeal).

Code completion in NetBeans' FXML editor is nonexistent. That "No suggestions" popup follows you around like a crap genie.

Refactoring support is also lacking. Here’s an FXML element describing a column in a table:

<TableColumn text="Instrument" fx:id="instrumentCol" />

You can link this to a Java field via the @FXML annotation:

@FXML TableColumn instrumentCol;

But if you use Ctrl+R to rename the field then you'd also expect the element's fx:id attribute to be renamed. No such luck. To make matters worse, there's no compile-time safety. The botched refactoring would not be caught by the compiler; instead at runtime you get a cryptic NullPointerException, which beginner developers are going to love. If the mismatch is between the Java field and the data class's corresponding property, there's not even an error: the code just fails silently and doesn't populate the table cell.

Unit-testing hole

Lucky then that JavaFX has such amazing, comprehensive support for a unit testing safety net? Ah. Yes.

The lack of documentation on unit or acceptance testing suggests that it's not even an afterthought, but that Oracle hasn't even thought about it. There's no easy way to instantiate a partial Scene Graph for isolated testing. Sure it may be possible, but it isn't easy. In an age where developers are increasingly savvy to the need for unit tests, this stark avoidance of the subject by Oracle is perplexing to say the least.

Time to build

The reboot of JavaFX has produced what might politely be termed a "version 1.0 API". Simple errors are rewarded with quite scary and obtuse exceptions. Seemingly simple tasks (such as finding a component without having to linearly traverse the whole scene) are difficult and require some heavy lifting from the community to plug the gaps left by Oracle.

I'm sure the API will mature and grow over time, but at the moment certain tasks that should be simple turn into a gruelling hunt for examples. It is as if the JavaFX designers have launched into the stratosphere, wanking over how cool all the advanced stuff is, while forgetting to make the simple stuff simple.

TableView's data model is an ObservableList, a new Collections class unique to JavaFX. An ObservableList fires off events any time its elements are added or removed. This allows the TableView to automatically refresh any time the data changes. But does this approach scale?

I set out to write a tester app that would pummel TableView with "live" updates, to see if the UI remains responsive. The use case was to have a table with 10,000 rows and 1000s of real-time updates per second. My first try was deliberately naïve: after populating the table, it then flung a randomly updated row at the table's ObservableList, 1000 times a second. Obviously a real app wouldn't do this. It would pool the updates, throw away the stale deltas, and unleash batched updates at a less frenzied rate.

Nevertheless, the table coped surprisingly well: the UI remained responsive throughout. The same approach with a Swing JTable would have locked up the whole app. It pretty much made my second test obsolete, which was to send batch updates every half-second at the table. TableView's innate ability to cope with high-frequency updates could turn out to be the platform's saving grace, and a reason for companies with low-latency requirements to adopt it.

The word "integration" can be applied only charitably in this case of Swing and JavaFX. Co-existence would be a better description. While a JavaFX Scene Graph can be added into a Swing container, making them play nicely together can get hacky. Both toolkits follow a single-threaded UI model. However, they use different threads for the same purpose: Swing uses Event Despatch Thread (EDT), while JavaFX introduces the User thread. Programmers will end up hopping back and forth between these two threads in a sword-hopping Highland Fling: inevitably there will be some cut feet in any non-trivial applications.

New platforms

The reverse situation, adding Swing components into a Scene Graph, was dropped from this release, although the community is trying hard to produce an interim solution.

It may not sound like it, but I'm rooting for JavaFX: I want it to do well. And I'm sure that over time it'll mature into something wonderful so long as Oracle doesn't drop it as Microsoft and Adobe have dropped Silverlight and Flex/Flash.

But progress is woefully slow. The lack of a GUI editor indicates NetBeans has slipped back to its contented, cud-chewing ways, while Adobe pushes ahead with HTML5-based interaction tools; and Flex, as long as it's with us, has a sublime visual editor - which it's had since 2006. Meanwhile, Flex is already multi-platform and can be deployed on iPhone and Android.

JavaFX needs a strong signal from Oracle that they're going to continue to back it, or make it somehow more relevant to the HTML5 age. Just, please, no more reboots. ®

Matt Stephens is a Java consultant in Central London. He recently launched a travel writing site, founded independent book publisher Fingerpress, and co-authored Design Driven Testing: Test Smarter, Not Harder.