Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/11/23/charles_eicher_mobile_classroom/

Huge PDP-11 in a lorry: How I drove computers into schools

Mobile technology, the mainframe way

Posted in Software, 23rd November 2011 15:42 GMT

This Old Box Computers in classrooms are so common today, we may forget this was once inconceivably difficult. Computers were very expensive and so large they needed a huge truck to transport them. Nearly 35 years ago, I worked on an ambitious but ill-fated project to bring a minicomputer to rural Iowa schools, a classroom on wheels.

In the autumn of 1977, I was a sophomore at the University of Iowa. I’d had access to the university's computers for the past six years, under their initiative to teach computer science to students as young as 12. I had recently built a SOL-20 microcomputer from a kit, was enrolled in CS classes, and worked part-time as a junior programmer for the university.

I usually worked on experimental educational projects, and one day I was offered an exceptional project. The university had another initiative, to bring Computer Assisted Instruction (CAI) to schools across Iowa. In the late 1970s, even a simple 300 baud modem was exotic equipment, and computers in schools were unheard of. There was an active CAI program on campus, but it was impractical to bring teachers from across the state to the computer facilities. So the university would bring the computers to the schools.

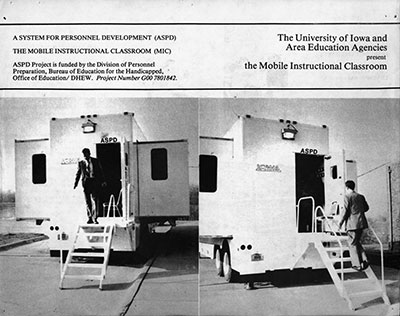

The Mobile Instructional Classroom, as it was called, would put a DEC PDP-11 minicomputer and 16 terminals into a massive semi trailer and drive it to schools throughout Iowa.

It was a very ambitious setup – especially as the trailer had expanding wings to double the room size. I suggested to the project director that since schools already had classrooms, it would be easier and cheaper to buy some inexpensive microcomputers and install them in a spare classroom or the teacher's lounge.

The project's thrilling brochure

I suggested a newly released computer called the Apple II. My idea was immediately dismissed. The director insisted that Apple computers were only suitable for playing Pong and Breakout, they were incapable of "serious" computing. So I suggested something more "serious", an IMSAI or even a SOL. The director insisted that since they had already purchased the trailer and ordered the PDP-11, they were committed to the project as designed.

Writing software the old-fashioned way: with printouts

The project's software content was intended to help teachers recognise learning disabilities like dyslexia, and give them ongoing education and improved teaching certification.

The software originally ran on an IBM 1500 Instructional System, designed exclusively for CAI courses and written in a unique language, Coursewriter. But the IBM 1500 was obsolete and was decommissioned.

The last act of decommissioning was to print out all the programs, resulting in a stack of green-bar paper about 6 feet tall. My job was to learn that dead language, then rewrite the software in BASIC so it would run on the PDP-11. The framework was simple, the courses presented a section of instructional text, some multiple choice questions and a scoring system.

So, I found myself the senior programmer on the project. I helped write some of the new BASIC software, experimenting on my SOL at home. I borrowed a Carterphone 300 baud acoustic coupler modem from the project and wired it up to my SOL so I could write code from home.

The framework was designed so typists that were untrained in programming could read the content from the printout and type the BASIC code around it without having to understand how it worked.

This is where the troubles began

The PDP-11 hadn't shipped yet. So we wrote the software in an ANSI-compatible version of BASIC on a CDC Cyber mainframe. A dozen typists were hired, and put to work on dumb terminals in the computer science building.

The software was written in using a primitive line editor, a word processor that only showed one line at a time. The results were predictably disastrous. There were so many typos and errors, it took more time to fix their code than it would to just write it all by myself. So I did.

I had my SOL and a modem so I could work at home, but the typists only worked an hour or two each day. I was supposed to work in the office, but that would just make me available to fix everyone's bugs. So I started taking an inch or two of paper off the printout stack home with me, spending late nights typing it in.

The director didn't seem to notice the stack getting shorter, or the stored files getting larger. He would question me about why I was never in the office, but my time cards showed so many hours of overtime. I showed him my file storage, he couldn't believe I was doing more work than the rest of the team. Over the next few months, I coded about 90 per cent of the project by myself.

Your laptop? Show me your car park-top

Throughout the cold winter months, we wrote the code and tested it on the Cyber mainframe, consistently falling behind the director's optimistic schedule. Cyber BASIC was compatible with the DEC. I thought it was clever that we'd used an ASCII system

instead of the university's IBM/360, which used their proprietary (and incompatible) EBCDIC. That would have been a problem. But nobody noticed that we had no way to move the software from the Cyber to the PDP-11. The director planned on dumping the code to a DEC disk pack, but the format was incompatible with the Cyber. Eventually we found a contractor that had a DEC and a CDC computer on the same network, and could convert our tapes. But these unexpected delays were putting the project behind schedule.

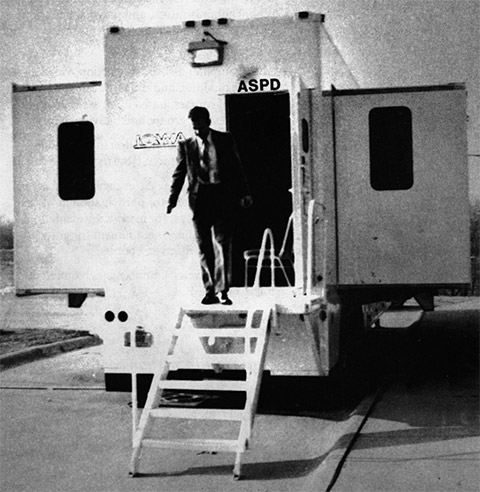

Tiring work - and that was just opening it up

The director wanted us to practice deploying the trailer, before the computer was installed. So occasionally we would visit the empty trailer, standing out in a snowy field in the freezing cold, open the wings to expand the room. Then we'd fold it back up. The wings expanded with a manual crank. It took considerable strength to turn the crank, none of us could work for more than a minute or so. It was exhausting.

The floors folded up and were retracted by an electric winch. The director wanted to show us that the winch had no automatic shutoff, so we had to be careful to manually stop it or it would snap the cable. I was watching from outside, underneath the floor, so I could see how this worked. Of course the director snapped the cable, dropping the heavy floor right over my head. A moment before, I was standing in the open floor area. I could have been killed.

In the spring (several months late) the PDP-11 arrived and was installed in the trailer. The minicomputer was installed by DEC engineers; they couldn't believe what they saw. The trailer was hooked up directly to an electric power pole, and grounded by a big copper stake hammered into the earth.

The power was too unstable to run a sensitive computer and engineers from the local power company had to come to fix it. Power grids in Iowa were notorious for voltage fluctuations; a typical 120V AC line could be anywhere from 100V to 130V. The 60Hz AC cycle could vary, disrupting the system clock.

More delays.

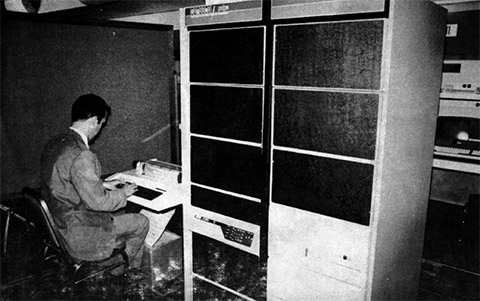

A Portable Computer: circa 1977

The computer finally became operational and more equipment was delivered. The PDP-11 occupied two full server racks, and had a removable disk pack so the delicate media could be dismounted during transport.

We received two terminals to join our DECWriter system console. I began working in the trailer, preparing the system for its first live test. I asked the Director when the other 14 terminals would arrive. He said this was it. The project had run over budget, now they didn't have enough money to buy more terminals.

I was scheduled to help deliver the trailer for its first run, but I could leave that to others. The director planned to make a big splash, delivering the high-tech truck to a small rural town. It would spend a week there and then move to another town every week. I visited the site during deployment. The electricians spent 3 days stabilising the power source. Now there were only two weekdays to finish the courses, and only two teachers could use it simultaneously.

After all this work to create and transport an enormous truck full of 16 terminals, and only deploying two, it seemed like we were transporting a huge room around with almost nothing in it. I had worked for nearly a year, to deliver almost nothing. My software job was done, so I moved on to another project. I never heard of the Mobile Instructional Classroom again.

New developments in microcomputers like the Apple II revolutionised educational computing overnight. The ambitious mobile classroom project was obsolete before it was even launched. But for a brief moment, it tried to raise the standard for computing in the classroom, at the same moment a new standard emerged. ®