Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/10/31/sony_ericsson_retrospective/

Farewell then, Sony Ericsson

The Reg looks back over a rollercoaster decade

Posted in Personal Tech, 31st October 2011 14:57 GMT

It promised to bring together the best of Swedish design and Japanese consumer electronics marketing, and at times, it did. But after 10 years and one month, Sony has pulled the plug on its mobile phone venture with Ericsson.

The venture was born out of necessity, with two great storied giants forming a sort of losers' alliance. A decade later it ended with sales in free fall: SE's shipments were just a quarter of their peak of four years ago, and staffing a third of the 9,000.

Both parents had pretty illustrious pasts behind them. In 1876, electrical engineer Lars Ericsson began repairing telephones made by Alexander Graham Bell, and realised they could be better designed. Within two years he was doing just that, and his company dominated both consumer and network technology for over a century. The Swedes designed the rotary telephone, which remained unchanged until the 1980s.

Meanwhile, Sony had created markets for portable music and games.

The two parents also had other assets. Sony had a movie studio and a record label (and publisher); Ericsson had the network expertise and an inside track on standards. These should have been enough to keep the newcomer in Tier 1 for a very long time, with enough muscle to seriously challenge the leaders.

Sony Z5 from 2000:

the wheel-based UI was incorporated into later products

Sony had not been able to replicate its success in portable games and music devices, and by the end of 2000 Ericsson was also struggling, as Nokia's simpler, cheaper and more friendly phones were embraced by the mass market.

A partnership between the two was unusual, and on paper, it was very promising.

The JV would be free from the sprawling bureaucracies of its parents. Sony encouraged divisions to fight each other, and even sabotage each other's products. Ericsson invested hugely in R&D and design but had problems getting products to market, and then marketing them attractively. For its part, Sony would bring its global brands to the phone business. A joint venture could be more entrepreneurial, finding opportunities faster and executing more quickly. In theory.

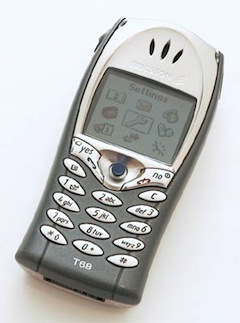

It was fortunate that the joint venture embarked on its journey with a hit. This was Ericsson's T68, released at the end of 2001, and became the ailing Swedes' comeback phone.

The T68 was colour, a blotchy, grainy colour by today's standards, but even a year later most devices on sale were still monochrome. It had Bluetooth, which Ericsson had devised and nurtured. It was tri-band, supporting US 1900Mhz frequencies. Best of all it was small and svelte; Ericsson's earlier models had been characterised by its stubby, signature antenna, just when Nokia's engineers were making the antennas disappear.

With these assets people could overlook the flaws. Within 18 months Sony Ericsson had fixed these, and was producing (in the T610, and the K700) incredibly slick-looking consumer gadgets for a low cost: a real manufacturer's dream, which translated into healthy margins. And so SE was well placed to reap the reward when Nokia stumbled in early 2004. Nokia had neglected its mid-range, which looked crude and shabby compared to the slick, themable UIs of the Sony Ericsson feature phones.

The Ericsson T68: ensured the joint venture started with a hit

In addition, Sony Ericsson had produced the most eye-catching new phone of the decade – one that even caught Steve Jobs' eye – the P800 smartphone. This was refined less than a year later in the P900, the high point of the joint venture's design and technology efforts. Of all the smartphones produced before Apple entered the market, this crossed the bridge between the needs of advanced IT users and people looking for an ordinary business phone.

Strangely, the Bluetooth Watch failed to save them

Unfortunately by the mid-noughties the smartphone market hadn't taken off in the way the industry had hoped it would, and as a result, the operators became more conservative and reasserted their control. The handset manufacturers didn't have the market clout to insist on bundled data plans. Vendors such as Sony Ericsson no longer took risks, so phones that had "smart" capabilities such as running third-party applications simply began to resemble larger and clumsier versions of voice-centric phones. The market was ripe for a new entrant that made data services nice to use, and voice an afterthought.

Sony Ericsson's futuristic P800i, from 2002

Following the success of the iPhone, Sony Ericsson was scrambling around for a platform on which to base its great designs and consumer brands. Having dallied with Windows Mobile, it eventually arrived at Android, but Samsung and HTC were moving faster and with more resources. It remains to be seen whether those investments in Android UI were ultimately worthwhile. Sony Ericsson found itself trying to put out fires: launching and then abandoning a low-cost initiative for emerging markets, and seeing its midrange wiped out by the rush for smartphones.

Anyone remember the Sony Ericsson bluetooth watch? Thought not.

What's interesting is how those assets turned out to be assets they couldn't really use. There's no point being the world's largest infrastructure player when you can't leverage that inside knowledge. And while SE tried to innovate with music services, you rarely felt that these had been put together with the help of privileged insiders at a large Hollywood company, as they were.

Cybershot and Walkman developed into recognised phone brands, but the best-known brand, PlayStation, was withheld from the JV until it was too late: a "PlayStation certified handset" was only announced this year. And arguably, the branded phones rarely lived up to the lustre of their grown-up reputations. SE didn't really do much to enhance its platform, which in 2009 looked very much like it did in 2003.

Sony Ericsson hasn't been alone in suffering: Siemens couldn't stay the course, while Motorola and Nokia went into free fall too. But is there a reason why Sony might now succeed, while Sharp and Panasonic (Matsushita) - two giants who retreated to the Japanese domestic market - couldn't? If there is, you'll have to tell me what it is.

Otherwise, the venture's most valuable legacy today looks like an IP portfolio. ®