Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/09/10/how_september_11_changed_our_world/

9/11: The day we lost our privacy and power

Every day, we have to prove we have 'nothing to hide'

Posted in Legal, 10th September 2011 10:00 GMT

Investigative reporter Duncan Campbell reflects how 9/11 has torpedoed resistance to intrusion and undermined privacy rights born of earlier struggles. It may, irreversibly, have changed the way we think.

9/11 was a savage nightmare that took too long to happen for some in the West.

For 12 fallow years, from the fall of the Wall to the fall of the Towers, there was a brief golden period in which no great common enemy menaced all unseen beyond the distant horizon. There was no simple spectre of fear on which to construct, fund and operate surveillance platforms, or reason to tap data funnels into society's communications and transport arteries.

Through the '90s, in debates about the control of communications and electronic security measures – amid a US-led hue and cry for government control of all cryptography (remember the "Clipper Chip"?) – the "what if" question hung always in the mouths of the proponents of more control. What if terrorists had a nuke? A new virus to plague civilisation?

But the bad guys largely stayed off stage. The inter-Irish conflict that had dogged the UK had subsided into a peace process. There was a global terrorist shortage.

Then the catastrophe hardliners had secretly longed for was on everyone's screens, providing the justification for rafts of intrusive new surveillance measures. The common criminality that caused carnage in New York and Washington was elevated to a war that became the GWOT, the global war on terror that endures today.

It seems that on that day, and for the sake of that war, civil society's power to control surveillance of the wired world has eroded, and with it the moral authority to impose controls on what shall be done in security's name. The zeitgeist has changed.

Much aided and abetted by the internet giants' readily expressed contempt for privacy in the rush to monetise their customers and their customers' data, the long-term legacy of 9/11 is that new generations are being schooled to no longer see or understand why control of personal information may really matter, and why in history it does and did matter.

"Warrantless wiretapping" of the internet and other intrusions have become a fact of life. When secret agreements made by the US National Security Agency (NSA) to access American telephone and cable networks started to become public in 2005, it was soon apparent that they had been made unlawfully, on the basis of questionable and undisclosed secret authorities from the Bush White House given after 9/11.

Privacy advocates fight back

But when lawsuits started by the Electronic Frontier Foundation and other privacy advocates started to gather traction, the rules were changed. Supported, sadly, by Senator Obama before his election, the lawmakers handed out get-out-of-jail-free cards indemnifying the communications companies and their executives from prosecution and lawsuits. GWOT was their trump card.

Once, we did understand. Twenty-five years ago, Independent science correspondent Steve Connor and I wrote a tome about Britain's Databanks and the effect of growing data processing on civil society. Steve had located Britain's first ever vehicle Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) device, a washing-machine-sized contraption planted on a motorway bridge near St Albans. It heralded the potentially tyrannical ultimate development of a nationwide movement surveillance. We both reached for and proclaimed words from early reviews of data protection laws that had warned that new sensors and new software such as free text retrieval (FTR) raised "new dimensions of unease".

A quarter-century on, these words are all but unsayable. The thoughts no longer fit the world. Every sort of record is analysed in every way. A vast nationwide ANPR network is in place and growing every week, collating years of movement records in a Hendon database for potential analysis for any purpose. Every traveller, whether of current interest or not, has her or his movements logged. There was no parliamentary debate. Only on one occasion, in Birmingham, has an ANPR network been rolled back from a community targeted for intense surveillance.

For now, ANPR sensors placed around Britain's roads remain marginally distinguishable from "ordinary" traffic cameras and CCTV (since they feature infrared illuminators and require at least one camera per lane). But that will change within less than a decade, as the signatures of these and other new surveillance devices vanish to invisibility.

For this writer, the political effect of 9/11 was immediate, personal and direct. Six days before the towers came down, the European Parliament had passed 25 recommendations for securing domestic and international satellite communications from the Anglo–American surveillance system known as Echelon.

I had uncovered and first reported on the Echelon network in 1988. It took a decade more for its significance to become widely known, mainly because of further investigation and revelations by New Zealand investigator Nicky Hager in his book Secret Power.

Although now widely mis-described in web chat as a generalised surveillance octopus, Echelon's purpose and hardware was quite specific. In 1969, new receive-only satellite ground stations were built in Cornwall, UK and West Virginia, USA, and soon after around the world, to copy and analyse all international satellite communications.

That part of all international communications which was digital – communications addresses, data streams, faxes and telexes – were fed into early text-recognition software, the Echelon Dictionary, and then extracted and fed out.

In 1999, the European Parliament commissioned reports on Echelon, and then asked for further checks and legal recommendations for controlling spying from EP vice president Gerhard Schmid. Schmid's detailed recommendations were passed without exception by the full parliament on 5 September 2001. They would have been an important new step to protect the privacy of global communications. But in less than a week, the project to control Echelon and its like lost moral authority. The proposals soon sank into the dustbin of history.

In their wake, quite apart from the now well-publicised episodes of kidnapping (rendition) and torture, a new archipelago of monitoring and control and extrajudicial punishment has come into being. The US has according to a major new study published this week, created a vast and almost unseen archipelago of secret operations and control centres.

Top Secret America is the product of two years' of research by former military intelligence analyst Bill Arkin and a team from the Washington Post. They found that since 9/11, more than 1,200 government agencies and 2,000 private corporations at over 10,000 locations within the United States alone have created an unstoppable and barely controllable top secret network to support the GWOT.

Like Arkin and his team, I have tramped around recondite suburbs and industrial parks in Maryland, Virginia, Washington, Colorado and elsewhere to view the architecture of this new world. In Washington alone, the new homeland security, intelligence and counterterrorism real estate includes 33 new building complexes erected since 2001, with a net floorspace 22 times greater than the Congress.

Constellations of these centres have grown everywhere: in the UK at Menwith Hill in the Yorkshire dales; in the US in Texas, Georgia, Colorado. The monolithic and windowless nature of the buildings is dictated by an extreme electronic security requirement that they be SCIFs (Secure Compartmented Information Facilities). Apart from physical security and personnel control systems, the signature physical aspect of a SCIF is that no electronic emanations reflecting what happens inside should be carried out by cable, fibre or through a window. Not a photon shall escape.

Some are merely windowless and featureless blockhouses. Others sport multiple satellite connections that supplement the buried and unseen fibre global networks.

Bolling Airforce Base on the Potmomac.

Denver and Buckley buildings

Arkin and co–author Dana Priest conclude that "hardly anyone truly comprehends the enormous expansion of the military, intelligence and homeland security bureaucracy that has occurred over the past decade, and the often irrational transformation of American life that has accompanied it."

Some centres manage satellites. Others collate and assess information harvested from the internet. Modern warfare bases in Nevada and California and on the east coast house control centres for the growing fleets of UACVs which can remotely administer final punishment on those considered to be threats. No courts or judges are required, or indeed allowed in.

A large part of the new technical apparatus since 9/11 is devoted to filtering international communications passing through the United States, including the communications of American citizens. Thanks to courageous whistleblowers and the persistence of campaigners such as EFF, details of NSA's surveillance network have been coming to light since 2006. Wiring plans and fibre schematics provided by a former technician for the communications company AT&T showed how optical fibres running through their San Francisco hub had been spliced and tapped to take much of the United States' west coast internet traffic into a secret monitoring room, and on into analysis centres.

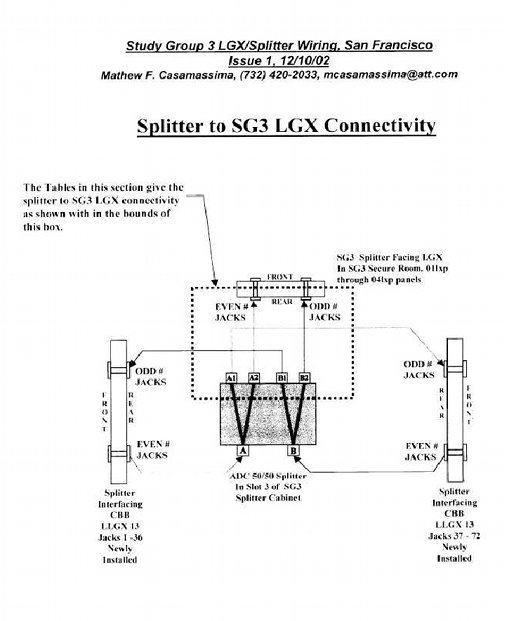

Wiring plans and fibre schematics provided by a former technician for the communications company AT&T

Further and later investigations showed that the plans for the San Francisco and other taps into the global internet had been developed in the late 1990s, but that the full–scale go ahead was only given late in 2001. EFF assessed that there might be hundreds of similar access points spread through communications centres.

Pivotal to sanctioning breaches of law and the setting aside of historic protections that the United States had gained after the War of Independence and in its Bill of Rights, was a lie about terrorists and computers. The lie remains on the internet to this day.

On 6 December 2001, US Attorney General John Ashcroft – desperate to leverage support from the US Senate for the radical post 9/11 PATRIOT act that would hand the government powers unprecedented in peacetime – announced the publication of an "Al Qaeda manual" found by the US government. The manual he said, was "a "how– to" guide for terrorists – that instructs enemy operatives in the art of killing in a free society … in this manual, al Qaeda terrorists are told how to use America's freedom as a weapon against us. … Imprisoned terrorists are instructed to concoct stories of torture and mistreatment at the hands of our officials." (sic)

The manual was allegedly "found in a computer file" described as "the military series" related to the "Declaration of Jihad".

Among the many problems with these assertions is that the document Aschroft described was not on a computer and could not have been. It was a limited edition paper book prepared in the 1980s, at a time when Al Qaeda did not exist and when Mr Bin Laden was helping run a guesthouse for fighters supporting the US-backed attacks on the Soviet occupiers of Afghanistan. It was souvenir from that first war kept by a fighter who had moved to Manchester, England.

When the police called on him in 2001, there were no computers in his house. He handed it to them and told them what it was. The rest of the story was made up in Washington after 9/11.

The book is not called the al Qaeda manual, and does not mention al Qaeda or Osama Bin Laden. Its target was not the West but rather corrupt Arab states. It was written at a time when the Soviet Union was ruled by the communist party. The manual is still online, and still dishonestly described, here.

Can the zeitgeist change back? Part of the problem lies in the construction of journalism in approaching privacy issues. No newspaper or magazine wants to talk about theory or abstract principles. Anecdotes rule the day. Editors want victims of the putative harms of excessive surveillance. And not just any victims: they want fresh new and charismatic victims whose stories are exclusive to their outlet, whose allegations and fears are sufficiently well documented and clear to satisfy lawyers, yet simple enough to slim to a soundbyte.

This is not a new structural problem in journalism or politics. It can make it hard for many to argue against the jibe that they have "nothing to hide". This is never true, of course, but it leads an informed audience away from the central harm, which is that it is the existence of uncontrolled surveillance and (critically) the power to act on its results, that causes harm to society. This is the "chilling effect". Fear, no more and no less.

Enhanced fear has now been common currency for a decade. It could be why – following Winston Smith, the central character of 1984 – that since 9/11 we may all be headed to a time why we don't understand anymore why privacy matters.

Perhaps part of this may have been inevitable, driven by Moore's Law and the related effects of decades of exponential growth in IT capabilities. What 9/11 has done to take away the idea that we should have the power to control what happens next. ®