Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/05/26/orion_mpcv/

NASA 'deep space' ship: Humans beyond orbit by 2020?

Just maybe – if Elon Musk can do what he says

Posted in Science, 26th May 2011 10:00 GMT

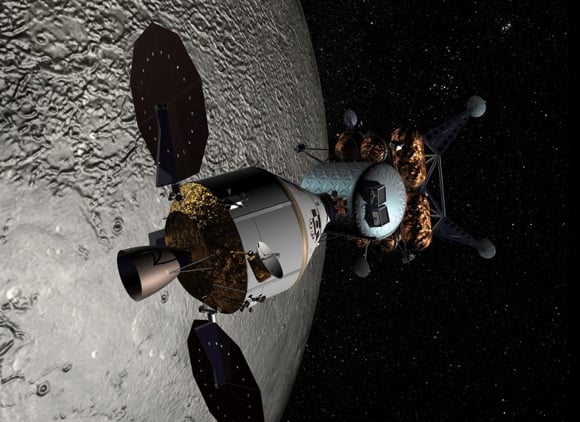

Analysis NASA has declared that its pork-tastic Orion moonship – whose primary mission disappeared with President Obama's decision that there will be no manned US return to the Moon – is now to be a "deep space transportation system", suggesting that the agency plans to send it on missions beyond Earth orbit.

Well, this isn't happening any more.

It remains unclear how the newly-renamed Multi Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV) will travel into space, when it will do so and what its destination might be – though a near-Earth asteroid is a likely possibility. A major reason for Orion's continued survival appears to be ignoble porkbarrel politics – but there is a tantalising possibility that it might fly beyond Earth orbit in the relatively near future.

The history of Orion stretches back to 2004. The Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle was conceived as part of the "Constellation" plans envisioned under the previous Bush administration. These would have seen NASA allied with the established US defence-aerospace industry to mount an ambitious manned Moon-return/Moonbase programme, seen as a precursor effort which would build manned beyond-low-orbit expertise and hardware to be used in an eventual Mars mission.

Under Constellation, not only Orion but an Altair moon lander would have been built. Ares I person-carrying and massive Ares V cargo-only rocket stacks would also have appeared, using technology developed under the Shuttle and Apollo programmes and delivered by traditional cooperative efforts involving large workforces both at NASA and the aerospace majors.

The problem with Constellation was that it was terrifically expensive and NASA's manned-space budget – even on the basis that there would be a gap between cessation of Shuttle flights and commencement of Ares/Orion ones – could not cover it. Congress declined to provide a budget boost of the sort which President Kennedy had managed to obtain for the previous Apollo moon programme.

This led President Obama to institute a review process on taking office, following which almost all of Constellation was axed. The first task which had been foreseen for early Ares/Orion missions – that of carrying supplies and ferrying crews to the International Space Station – was handed off instead to new commercially-built ships (and even rockets) which would be produced without major involvement by NASA – and perhaps without any input from the established aerospace firms either.

The question of manned missions beyond Earth orbit was punted into touch, with the President stating that there would be no return to the Moon and that the goal was now Mars – with the prospect of manned missions to Lagrange points and asteroids beyond lunar orbit as stepping stones at some point. A decision on the heavy-lift rocket which would be necessary to assemble Mars missions in Earth orbit was postponed until 2015.

It's going to be a 'deep space' manned ship ... where's the man-rated rocket?

The president had reportedly planned to axe Orion along with all the rest of Constellation, but at the last minute – possibly as a sop to the large space-industry and NASA workforces facing the sack in the wake of the Shuttle programme and the axing of Constellation – Orion was reprieved. It lacked any obvious task in the near future, and with the demise of Ares I there was no prospect of any man-rated rocket able to carry it being ready at the point when Orion would be completed. It was stated at the time that the orphan ship might be launched unmanned to dock with the ISS and serve as a crew lifeboat, though Russian Soyuz craft were already performing this role without difficulty and one would never keep on building Orion just for this.

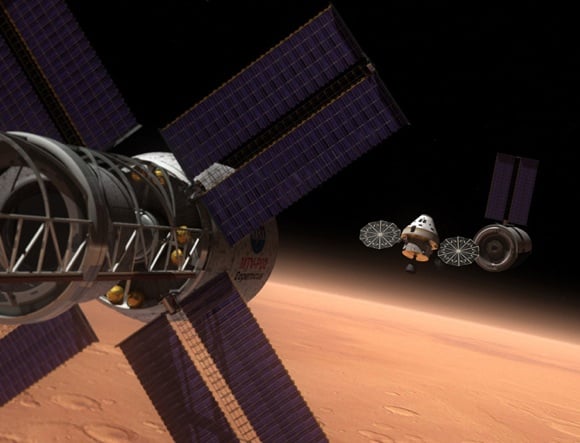

Nor is this

You might alternatively keep Orion going for use in the projected deep-space missions of the future, but on stated plans the lifting rockets and the funding for these will not be ready until well into the 2020s: even the heavy-lift rocket decision is not until 2015, a year after Orion/MPCV is supposed to be ready. The ISS has now had its life extended, too, which will eat up US manned-space funds. A development timeline of 20 years and more from its 2004 kickoff to first flight would make Orion very expensive indeed: financially it would probably make more sense to mothball it or scrap it and start over again once the deep-space plans firmed up. Probably cancellation followed by a new ship would work out cheapest, as Orion is an old school, cost-plus, joint effort between NASA and established contractors led by Lockheed. Almost any kind of new and more appropriately-timed effort would be likely to cost less.

None of this background has changed: this week's announcement by NASA doesn't at first sight mean that anything new has really happened other than some contract shuffling. What it really says is that the agency and its Obama-appointed director Charles Bolden are formally committed to resisting cancellation and keeping Orion, sorry, MPCV alive until the deep-space era eventually begins. That will be politically beneficial, as NASA's pork map shows.

It also seems that Bolden and NASA intend that the 2015 heavy-lift rocket decision should be made in favour of the contender being designed by NASA's in-house team for build along traditional agency-plus-industry lines.

"The NASA Authorization Act lays out a clear path forward for us by handing off transportation to the International Space Station to our private sector partners, so we can focus on deep space exploration," says Bolden in a tinned quote. "As we aggressively continue our work on a heavy lift launch vehicle, we are moving forward with an existing contract to keep development of our new crew vehicle on track."

No matter who builds the heavy lifter, it won't be ready until the 2020s. Why does NASA want a deep-spacer now?

NASA's planned Space Launch System heavy lifter is a sort of Shuttle without the orbiter, which would look a bit like a Shuttle fuel tank and strap-on boosters with some Shuttle main engines attached at the bottom, plus payload, upper stage etc mounted on top. In time, parts of this might be replaced by former Ares/Constellation pieces developed before the axe fell.

This is certainly a long way off.

Exactly when the SLS could be ready is uncertain: a detailed report is expected this summer, but delivery seems likely to be at some point well after the original goal of 2016. Unsurprisingly NASA analysis suggests that SLS would be expensive to use, as it would run on cryogenic liquid-hydrogen fuel and would mean making and throwing away sophisticated Shuttle main engines every time rather than re-using them as has been the practice until now. Developed versions of the SLS might lift as much as 130 tonnes to orbit, and it would of course be man-rated.

In this vision of the future, NASA and its established Shuttle and Orion partners would build and run the entire US manned space programme apart from the ISS supply and ferry missions, which will of course disappear in the nearish future. This would avoid any uncomfortable need for job losses among the multitudes of NASA and aerospace-industry employees who have made the US manned space programme what it is today.

The problem here is cost: politically realistic levels of US funding probably can't mount much of a deep-space push – almost certainly not one as far as Mars – on this model of large traditional organisations using expensive traditional technology.

There is an alternative, though. Famous geekbiz-kingpin Elon Musk and his upstart rocket company SpaceX have come from nowhere in just eight years to successfully test-fly their brand new and very cheap Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon capsule, already apparently quite capable of performing the ISS supply mission. Only a few years ago, many in NASA and the established industry were arguing that this would never happen.

It's also no secret that Musk and SpaceX are working on a new Merlin 2 rocket engine, much bigger than the current Merlin 1 which propels the Falcon 9. A multicore heavy lifter based on Merlin 2 would be in the 100-tonne-plus realm required to mount a Mars mission, and will surely be the cheapest offering competing at the 2015 heavy lift Mars-rocket decision.

A further hint that SLS may be doomed is offered by the fact that Obama specified that one of the R&D efforts he expects to lead to less-costly space access would be "a US first-stage hydrocarbon engine for potential use in future heavy lift": in other words something a lot like the hydrocarbon-burning Merlin 2, and not much like the hydrogen-burning Shuttle main engine or derivatives of it.

Nonetheless there is a possible man-rated, Deep Space Lite™ option coming on stream before 2020

So NASA are quite possibly out of luck with their SLS aspirations, particularly if President Obama gets re-elected in 2012. And no matter who builds the heavy lifter, it would on the face of it seem that the Orion/MPCV deep spaceship will sit about costing billions and not actually fly anywhere for quite a few years. Musk's existing Falcon 9 doesn't have the grunt to carry Orion/MPCV, no matter that it seems likely to get cleared for manned flights fairly soon.

OK, Mr President, keep Orion if you have to. I'll get you something to launch it on

The sudden decision to rebrand the Orion as a deep space ship would seem to be nothing more than porkbarrel politics, then. Certainly, the President seemed to imply last year that it would be no deep-spacer but merely an ISS-lifeboat makework project. Why has he changed his mind? Is it merely because of that upcoming presidential election?

Obviously that must be a factor in Obama's thinking – and therefore presumably in Bolden's. But one does note that SpaceX has just unveiled a triple core, Merlin-1 based Falcon Heavy design intended to fly by 2014, supposedly man-rated and able to lift 50 tonnes to orbit. SpaceX is keen to use this to compete for business putting hefty US spy satellites into orbit.

However the Falcon Heavy would also be more than capable of carrying Orion/MPCV into space, with a fair bit of additional payload as well: perhaps enough to mount a small beyond-Earth mission right off. Certainly two Falcon Heavy launches, if the Heavy delivers to the planned spec, would be enough to put together a worthwhile little deep space mission in orbit. And if Musk's price quotes are for real, such a mission would potentially be cheap enough to happen really quite soon.

If Musk can get the Falcon Heavy flying on time and meanwhile show a safe and reliable flight record with its Merlin 1 engine and other common technology in the smaller Falcon 9, the case for manned Falcon Heavy missions late this decade would be looking strong. In the absence of a properly kitted out Orion/MPCV, however, there would be no candidate for a beyond-Earth-orbit ship ready to go*. The first missions would have to wait for the more likely 2020s timetable.

In this light, the decision to keep Orion and make it a deep-spacer might look reasonable to manned-space enthusiasts down the road, as well as deal-makers in Washington right now.

Obama could have largely achieved his political goals with a more basic, ISS-lifeboat-only Orion along the lines spoken of last year, after all. There's very little extra porkbarrel benefit in restoring the project's former status as a potential deep-space ship.

It seems likely that this week's announcement results at least partially from SpaceX's Falcon Heavy timeline revealed just last month. It seems at least possible now that if Elon Musk can do what he promises, space watchers may not have to wait yet another weary decade and more for the first manned flight beyond Earth orbit since 1972.

One has to note, though, that a good deal of insitutional inertia would need to be overcome at NASA for such plans to eventuate. As this is published, the agency has just announced a 2016 launch date for a robotic near-earth-asteroid sample return mission, OSIRIS-REx, spoken of as a necessary precursor to any manned asteroid mission. OSIRIS-REx would not return its sample to Earth until 2023. ®

Bootnote

*Musk has suggested that his company's Dragon capsule, once equipped for manned flight, would be capable of landing on Mars as well as Earth. However there's no suggestion that the SpaceX will be able any time soon to fit it with a service module and propulsion system suitable for long-endurance, long-range manned missions beyond Earth orbit.