Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/04/21/digital_economy_act_high_court/

What now for the anti-piracy law?

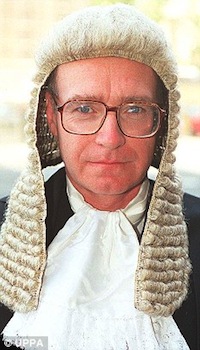

ISPs 'hoist with their own petard' says judge

Posted in Legal, 21st April 2011 10:30 GMT

Analysis BT and TalkTalk threw the kitchen sink, legally speaking, at the Digital Economy Act and made very little stick.

Reading the ruling, you wonder why they bothered. High Court Judge Kenneth Parker summarised the DEA as "a more efficient, focussed and fair system than the current arrangements". Over and over, he pointed out that the Act didn't actually say what the objecting ISPs thought it said. He reaffirmed the right of ISPs to not become snoops, or comprise their "conduit" role. Any snooping is going to have to be carried out by copyright holders. And the DEA doesn't suddenly make them liable for damages.

Parker gave BT and TalkTalk's lawyers a ticking off. At one point he found the ISPs' legal case so contradictory he said they'd hoisted themselves with their own petard. It wasn't the judge's role to favour one business interest over an other, he reminded them:

"It seems to me that if the Community legislator, as in this instance, has chosen specific language to give effect to a careful balancing of competing interests, the judge must be especially cautious before departing from the plain meaning of the text. To depart from that meaning creates the obvious risk of promoting the interest of one economic sector to the detriment of the other interested sector, and hence of seriously upsetting the balance between competing interests that the legislator has carefully struck," he notes.

The Act didn't actually say what technical sanctions (called "obligations") may eventually be introduced – and none may be. The technical obligations were "indicative, not exhaustive," the judge noted.

Nor did the DEA oblige the ISP to spy on users. "The role of the ISP under the DEA is essentially passive," he points out. The copyright holder must inform the ISP of specific suspected infringements, at which point the ISP must notify the user. It's no different to the role of the DVLC in giving out information identifying the owner of a number plate, said Parker.

Whether the Appeal for a Judicial Review was simply stalling or an expensive publicity stunt is a question that can only be answered by BT. They may wish to appeal, in which case it will drag on, but it's hard to see the EU Courts interpreting things very differently. The Act is sufficiently open-ended, and carefully worded, to see to that.

It's not all plain sailing from here, though.

The purpose of the Act isn't to make scapegoats out of hardcore infringers – who would dearly love to become martyrs for a day – and the determined, net-savvy user can bypass Torrent monitoring fairly easily.

Judge Parker acknowledged as much.

Appealing the appeal?

"It is not disputed that technical means of avoiding detection are available, for those knowledgeable and skillful enough to employ them. However, the central difficulty of this argument is that it rests upon assumptions about human behaviour. "

It's much more about reminding the household with the casual infringer that there will be consequences. The idea informing this is that the rational majority would then be nudged into listening to or acquiring music via licensed services. The cost of music has fallen sharply over 40 years, with an album now costing not much more than a cup of coffee.

Persecution fantasies such as this (from blog BoingBoing) are misplaced

"The DEA proceeds on the premise, first, that a significant number of infringers do not at the moment fully appreciate that what they are doing seriously infringes the legal and moral rights of others and that, although individual behaviour of this kind may seem trivial and excusable, the general effect may well be very damaging to the creative industries, a notorious example of what is sometimes called the tyranny of small decisions that have ruinous economic consequences," wrote Judge Parker. [Emphasis added].

He said education was one of the goals of the act, and it was reasonable and not unlawful thing for a Government to try to do.

"The recipient [of a warning] will be better informed about the nature of his conduct and of the likely consequences for others, and he may be disposed to cease, or at least to modify, such conduct. He may be persuaded to do so, even if it is contrary to his immediate interests: the days when it was assumed that consumers act only out of the pursuit of economic self interest, and do not, quite rationally, respond to moral, altruistic or longer term considerations, are long gone."

"Even if the selfish, determined infringer were minded to seek to evade detection, he might not be sure that technical means existed or were being developed to thwart him, and he might fear that, if he was detected, the new arrangements would be more likely to expose him to painful enforcement measures."

For a start, the Appeals Procedure could rapidly become a costly nightmare for everyone, but rights-holders in particular. Then there's web-blocking, which the BPI and others are desperate to see introduced to counter Rapidshare and Megaupload, and similar services. But web-blocking brings up a swarm of new problems. My bet would be that site-blocking is so problematic we'll see a fudge – with scary warnings providing roadbumps rather than roadblocks – and another round of pushing for tougher legislation.

The cyber-lockers are a problem that can really only be solved by a flourishing market. When Mandelson gave the Bill his backing he did so in the expectation that far more compelling services would be launched. He was pretty clear that they were needed. The government intervention would have to be matched by business creativity, and new markets. Given that it has been over two years since Spotify appeared, you have to wonder where they might be. ®