Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/03/10/ibm_investor_day_2011_palmisano/

IBM rides 'third supercycle of growth'

Big Blue predicts big profits through 2015

Posted in Channel, 10th March 2011 04:00 GMT

IBM hosted its annual investor briefing yesterday at the TJ Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York, which will probably go down in history as the place where the Watson question-answer machine (it is not a supercomputer, at least not yet) was built and whipped humanity's ass at Jeopardy!.

While the 20 top brass in attendance at the event gave their presentations on the mock-up of the Jeopardy! set and they made a joke here and there to the financial analysts in the stands, it was mostly seriousness as Sam Palmisano, IBM's president, chief executive officer, and chairman, and Mark Loughridge, the company's chief financial officer, laid out the plan to nearly double earnings per share between now and 2015 to $20 a pop through a combination of cost cutting, share repurchases, growth, and acquisitions.

Before getting into the prognostications and pronouncements, let's take a moment and talk about succession at IBM. It doesn't look like any of the current team are vying for any of Palmisano's jobs. As El Reg has said for a while, even though Palmisano would, according to IBM tradition, step down during the year he turns 60, it doesn't look like any of the current management team is apt to change before 2015 is over and the goals are reached.

Palmisano would be retiring this year, and that would be the centennial year for IBM if you take the June 16, 1911 founding date for the Computer Tabulating and Recording Company that was eventually renamed International Business Machines on February 14, 1924. But Palmisano's retirement seems far off in the future, particularly since no one at IBM has been anointed his successor, as Palmisano himself was by chairman Louis Gerstner more than a decade ago.

So the current configuration of IBM, in terms of the reconfigured business units and the executives running them, looks to be the team that Big Blue will be sticking with as its offensive front line. Maybe the new unofficial retirement age for IBM CEOs will be 65 when this is over. Or maybe it will be 70. Al lot will depend on how well what Palmisano and his team have planned out in meetings plays out in the real world of IT spending and the global economy that drives it or hinders it.

That plan is simple, and Palmisano made fun of himself in reviewing 2010's financials: $99.9bn in revenues, up 4 per cent; $14.8bn in net income, up 10 per cent; $11.52 in earnings per share, up 15 per cent, and gross profits up for the seventh straight year and net income, EPS, and free cash flow all setting records.

"Another record year in a tough environment," Palmisano declared. "I know it is getting boring: record, record, record." And he criticized the Wall Street analysts in the room for not quite believing that IBM could grow profits and EPS as it did in the prior ten years. Free cash flow increased from $6.7bn in 2000 to $16.3bn in 2010, and EPS nearly tripled, from $3.88 to $11.52.

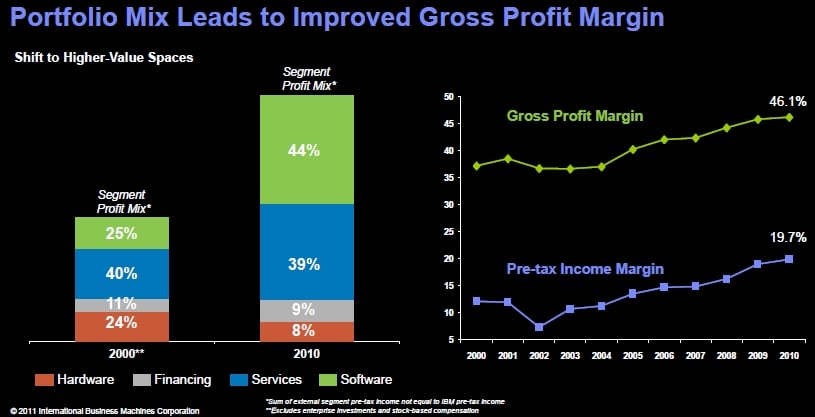

How did IBM do it? Part of the picture is right here in this chart that Palmisano showed:

What IBM did, as we all know, is ditch the PC, hard disk, and high-end printer businesses, which generated a certain amount of revenues for Big Blue and made it a more complete IT player. But these units don't make money, and if Palmisano learned anything in all of his years of tutelage under Gerstner, it was that the job of IBM was to make money.

"The new portfolio drives a heck of a lot more margin than the commodity hardware business," said Palmisano.

So it is no surprise that IBM has gone from a computer maker to a problem solver, which is why it is increasingly difficult to talk about Big Blue as an IT supplier. Perhaps a better name for the company today is International Business Manager, because generally speaking, IBM doesn't really care much about the machines except so far as chips, servers, storage, and the software that runs on them give it entre and account control into the data centers of the world. If IBM could sell off its hardware and software business and make even more money using commodity hardware, it would have done so already. And you know it.

So IBM has spent a tidy sum buying up services and software companies--some like Cognos and SPSS, which are relatively large, but many that are much smaller but which grow fast once IBM's 400,000-strong global workforce is pushing them--and building up its expertise in specific industries and research domains while at the same time investing in its core systems.

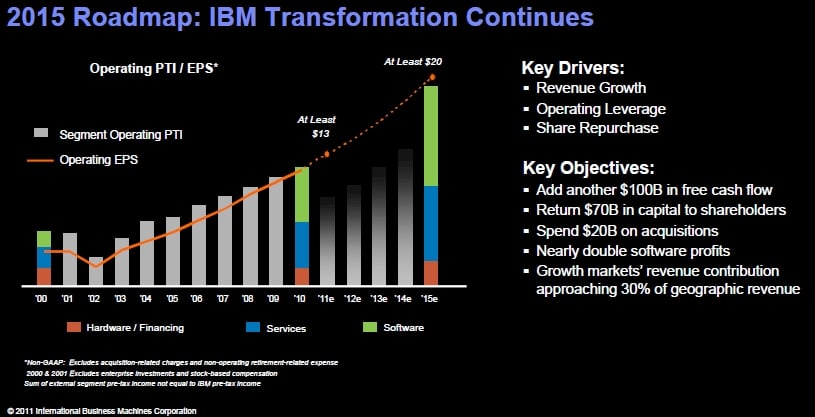

Since the end of 2000, IBM has spent $70bn on capital expenses and acquisitions ($16bn alone to buy 50 companies), $58bn on research and development, and $107bn on share repurchases and dividends. By any standard, this is a lot of cash. And say what you will about how share buyback cash might be better spent doing something else, the financial machine that Palmisano has designed looks like it has at least five more years in it, at least as far as the IBM top brass are concerned. Here's the roadmap going forward to 2015:

IBM thinks it can create another $100bn in cash flow in five years - nearly as much as it did in the prior decade - and do all kinds of interesting things with that cash. Or, more precisely, the same old "boring" things that Big Blue has done for the past ten years. This includes spending another $20bn on acquisitions and $70bn on share repurchases (which helps drive up EPS) and dividends. IBM's plan, said Palmisano, is to double profits in its Software Group and to eventually get to the point where the growth markets - the top 20 economies on earth ranked by gross domestic product expansion - contribute about 30 per cent of its overall revenues. Those growth markets, which include Brazil, Russia, India, and China, of course - are expected to contribute about 50 percent of IBM's overall revenue growth between now and 2015.

These growth markets are where the IBM top brass spend a lot of their time. And the reason is more complicated than the fact that you can get good (and real) Indian and Chinese food there.

IBM banks on the bourgeoise

Palmisano said that the world is experiencing what some people are calling "the third supercycle of growth." The first, of course, was the Industrial Revolution, and the second supercycle was the period running from the first World War to the period just after the second World War. And what is driving this supercycle "is not all of the things you read" but rather the "emergence of the middle class" in the rest of the world, according to IBM's leader.

Of the four pillars of IBM's future (and presumably modest) revenue growth and its rather more steep EPS growth, moving people and processes into these emerging markets to capture that opportunity is perhaps the most important one. Since 2003, IBM has been globalizing and standardizing its own systems, processes, and supply chain so there are not Baby Blue IBMs all over the world, each with their own stuff and cost centers, but one IBM, deployed like an army and backed by central command. The globalization of IBM's back office was timed, and not coincidentally, with its expansion into growth markets.

These efforts to consolidate back-end systems across the company pulled out $6.2bn in costs from 2005 through 2010 (inclusive), with about $4.8bn coming from what IBM calls shared services. This is the back end systems needed by branches and divisions to run themselves, including human resources, global sales, supply chain, real estate, finance, legal, IT, marketing and communications, and sales transaction software. In 2009, IBM started looking at how work is done in the company, and started ripping out costs - $1.1bn so far, and yes, those costs are people. Another effort to integrate operations across different units, started in 2010, yielded another $300m in savings.

Looking ahead to 2011 through 2015, Linda Sanford, the executive in charge of enterprise transformation within Big Blue, says that the company can do another $8bn in cost reductions by taking the shared services further and doing end-to-end process transformation and integrating operations. About $2.3bn in savings comes from shares services, $2.6bn will come from process transformation, and $3.1bn will come for better integration of operations across divisions.

Perhaps most importantly, IBM is only counting $3bn of that $8bn in savings in its model to get to the $20 EPS figure because it wants to leave a circuit breaker in there in case the economy takes a dip somewhere and revenue (heaven forbid) slows. IBM had an expense base of $80bn in 2010, and shared services was $11.4bn of that. Just to give you a sense of what the cost side of IT and back-office functions still is within IBM.

Loughridge said that the ease with which IBM can open branch offices around the world, thanks to these shared services, that will allow IBM to move from $30bn in revenues from its key four growth initiative - growth markets, cloud computing, business analytics, and smarter planet - to $50bn by 2015.

IBM's CFO put some numbers on these areas, as you would expect him to. IBM expects for business analytics to hit around $16bn in sales for Big Blue by 2015, and would contribute about 20 per cent of the company's growth. Cloud computing, while bringing in another $7bn by 2015, will also net only about $3bn in net-new revenue as IBM expects customers with strategic outsourcing contracts to shift to cloudy infrastructure. Smart planet, the hodge-podge of deals that mix IBM hardware, software, and services to help run transportation, water, electrical, and other governmental-scale systems, will hit around $10bn by 2015. That leaves the growth markets contributing around $17bn, if you do the math, and they will outpace the developed markets by about 8 points of growth, as they did before, during, and after the Great Recession.

This is where IBM is obviously very excited. Last year, it opened its first two research labs in the southern hemisphere - one in Brazil and the other in Australia - and moved into three new countries and added 42 branch offices, according to Bruno Di Leo, general manager of growth markets at IBM's Sales and Distribution unit. IBM had operations in 42 countries markets outside of North America, Western Europe, and Japan in 2000, with 95 branch offices. In 2010, IBM was in 53 growth market countries and had 218 branch offices, and by 2015, it wants to be in 78 countries with 451 branches. And not in the major cities, either. Di Leo says that 80 per cent of the IT sales opportunity in China, 63 per cent in India, and 72 per cent in the ASEAN countries is outside of the major cities. So IBM will need these branches to grow.

It's no wonder that IBM's top brass were talking all day about how they were "looping the world" and spending so much time in Asia, South America, and other fast-growing regions. If you could, you would too.

"There is a lot of confidence in Asia," Palmisano explained in a question and answer session follow the day of presentations. "If you ever want to feel really, really good about life, go to Asia. I mean, you can really feel good. Young people are inspired, there's a can-do attitude, governments want to work with you, businesses want to invest. You wouldn't recognize that you are on this planet."

That said, Palmisano said the developed countries (he singled out Germany because he was visiting the Chancellor, Angela Merkel, last week) were a lot more optimistic than two years ago, and that the outlook was a little more optimistic than it was even a few months ago in many countries.

Palmisano said IBM was sorting through all of the IT spending projections for the enterprise markets where it plays, and that things were looking better, quarter to quarter and year to year, with IT spending for 2011 being up maybe 3 or 4 points in the areas where Big Blue peddles products. "But people are cautious still. They're watching." But no one, said Palmisano, is just trying to "hunker down" to just cut costs anymore; everyone is trying to boost sales as well as cut costs. Just like IBM itself. ®