Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2011/01/21/computer_history_museum_revolution/

Gates, Woz, and the last 2,000 years of computing

If you program it, they will come

Posted in OSes, 21st January 2011 19:58 GMT

It's weird to see something from your childhood displayed as an ancient cultural artifact. Here at the newly refurbished Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, I'm standing over a glass case that houses the Commodore 64, the same machine I begged my parents to buy me for Christmas in 1983.

Compared to today's slick and smart personal computers, the Commodore 64 is the village idiot. With its 8-bit, 1MHz MOS 6510 processor and 64KB of memory, the only thing chunky about this machine was its famous built-in keyboard. But the Commodore 64 was in the vanguard of a revolution, one that took computers into people's homes by making them mass-produced, affordable, and usable by people without maths degrees or special training.

John Hollar with Bill Gates' Altair code (photo: Gavin Clarke)

The Commodore even bested the iconic Apple II – or Apple ][, as fanbois of the day wrote its name – which was designed by that company's larger-than-life cofounder Steve Wozniak. When Apple's pioneering desktop debuted in 1977, the entry-level version with a mere 4KB of RAM cost $1,298 – significantly more expensive than the Commodore 64's 1982 intro price of $595, which later dropped to $199. The Commodore 64 was so popular that sales estimates range from between 17 and 22 million units during its 11-year run.

The Commodore 64 is now among 1,100 objects that comprise a new exhibition called Revolution: The First 2,000 Years of Computing at the Computer History Museum. Assembled by an army of 300 people over eight years, Revolution fills 25,000 square feet and is the crown jewel of a $19m renovation of a museum that's been an easy-to-miss landmark of Silicon Valley – the spiritual home of the tech industry – since 1999.

$19m is a hefty dose of private philanthropy by any standard, and one that's all the more impressive given that it came from an industrial sector famed for entrepreneurs and engineers obsessed by the future, not the past. Among the donors to Revolution is Bill Gates, who also provided the establishing gift: the BASIC interpreter tape he wrote for the MITS Altair 8800 while at Harvard in 1975, and that led to Microsoft and Windows.

Museum president and chief executive John Hollar told The Reg on a tour ahead of Revolution's opening that the exhibit centers on thematic moments in computing. "If you knit all those together, you get an interesting picture of where we are today," he said.

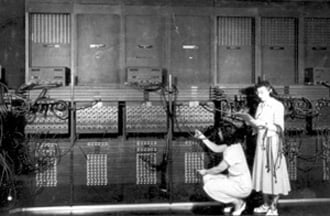

Revolution features pieces of the 700-square-foot, 30-ton ENIAC – Electrical Numerical Integrator And Computer – built by the US government between 1943 and 1945 to calculate missile trajectories. Not only was ENIAC the first general-purpose computer to run at "electronic speed" because it lacked mechanical parts, it was also programmed entirely by a staff of six female mathematicians who lacked any manuals and worked purely by deciphering logical and block diagrams.

There's also an IBM/360 from 1964, the first general-purpose computer for businesses that killed custom systems such as ENIAC that were built by and for governments. IBM staked its future on the IBM/360 – in today's dollars the project would cost $80bn.

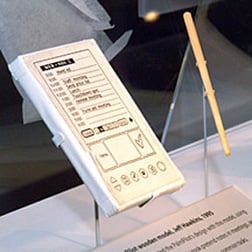

PalmPilot mock-up (photo: Gavin Clarke)

Revolution is home to one of Google's first rack towers, dating from 1999. Spewing Ethernet cabling down its front, the tower helped establish Google as a search colossus whose thumb is now on the throat of the web and society, choking out $23bn a year from online ads.

Is small and portable more your thing? There's the PalmPilot prototype and the original card and wood mock-up donated by Palm co-founder and Apple graduate Donna Dubinsky. With its stylus input, the PalmPilot became the first widely popular handheld device. The original models, the Pilot 1000 and Pilot 5000, predated Apple's finger-poking iPad by 14 years.

Revolution houses analogue devices that are more like workbenches, and is home to the first Atari Pong arcade game in its plywood case (which ignited the video-game revolution), a gold-colored Bandai Pippin from Apple (which disappeared without a trace), the Apple II, and the Altair that inspired Gates to eventually build the world's largest software company.

Overcoming the odds

While you can't view the actual BASIC interpreter tape that Gates wrote, the code has been immortalized in a huge glass plaque in the newly minted, airy reception area. Nerds take note: the reception area's tiled floor holds a punch-card design – work out what it says and you win a prize.

AltaVista on the Google rack (photo: Gavin Clarke)

"Knitting it all together," as Hollar puts it, means you shouldn't be surprised to see that 1999 Google rack server in an exhibit that goes back 2,000 years to the abacus.

"Will Google be remembered 100 years from now? That's hard to say," Hollar told us. "But what's more likely is what Google represents is with us forever - which is finding what you want, when you want it, where you are, and having an expectation that that information is going to be instantaneously available to you. That's unleashed a new kind of human freedom and those powerful forces that affect people at a personal and human level – they don't get put back in the box."

Revolution doesn't just show objects that are important to computing, such as the Google rack, it also tells the stories of their creation and their creators. Not just familiar names such as Alan Turing, but also the ENIAC women whose job title was "computer" and who were classified as "sub professional" by the army and disregarded by their snotty male managers.

Also featured are people such as integrated-circuit inventor Jack Kilby, whose bosses at Texas Instruments told him in 1958 not to bother with his project. Kilby pressed on regardless during his summer holidays, and presented the top brass with the finished article when they returned from their undeserved time away. Such jaw-dropping tales of achievement against all odds are explained with the assistance of 5,000 images, 17 commissioned films, and 45 interactive screens you can poke at and scroll through.

Thanks to its location in the heart of Silicon Valley, down the road from Apple, Intel, HP, and Xerox PARC – companies whose ideas or products now dominate our daily lives – it would be easy for the museum to present only a local feel to the story of computing, and to give a US-centric bias. With displays from Britain, France, Japan, Korea, and Russia, however, Revolution looks beyond the boundaries of Silicon Valley and the US.

A good example of the global focus is the story of LEO, the Lyons Electronic Office that's one of the least-known entries from Britain in the history of personal computing.

Back when Britain ran an Empire, J Lyons & Company was a huge food and catering company famed for running a network of nationwide teashops that refreshed stiff upper lips from Piccadilly to the provinces with cups of tea for the price of just over two old pennies.

Then, as now, catering had extremely narrow margins, and J Lyons took an early interest in computers to help automate its back office and improve its bottom line. Specifically, J Lyons was watching the work of Sir Maurice Wilkes at Cambridge University, where he was building EDSAC, the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator, that performed its first calculation in 1949. EDSAC was a pre-semiconductor dinosaur, using 3,000 vacuum valves and 12 racks, with mercury for memory, and that lumbered along at a then mind-blowing 650 operations per second.

The ENIAC monster (photo: US Army)

Lyons copied EDSAC and came up with LEO in 1951, regarded as the first computer for business. LEO ran the first routine office jobs - payroll and inventory management - while Lyons also used LEO for product development, calculating different tea blends.

Lyons quickly realized the potential of office automation, built the LEO II and formed LEO Computers, which went on to build and install LEO IIs for the British arm of US motor giant Ford Motor Company, the British Oxygen Company, HM Customs & Excise, and the Inland Revenue. LEO computers were exported to Australia, South Africa, and the Czech Republic - at the height of the Cold War. By 1968 LEO was incorporated into ICL, one of Britain's few computer and services companies, now Fujitsu Services.

The lion goes to pieces

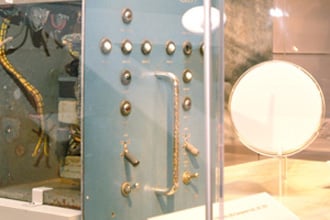

Two surviving fragments of the once mighty LEO were acquired for Revolution at auction in London: a cracked vacuum tube and a battered, grey-blue metal control box with buttons and flip switches that's more car part than computer component.

Lyons' LEO tea machine (photo: LEO Computers Society)

Alex Bochannek, the museum curator who showed The Reg around Revolution, told us he feels "particularly strongly" about LEO. "Our collecting scope is global in nature and the story of LEO is such a fascinating one, yet almost completely unknown in this country. This is why we decided to add these objects to the collection specifically for Revolution."

The $19m renovation and Revolution make the museum an attractive destination for visitors of all kinds and ages - engineers, non-techies, tourists, and those interested in the history of women in the workplace, to name a few. The museum is also trying to raise its game in academic circles, and Hollar wants to turn it into the premier center on the history of computing.

Just 2 per cent of the museum's entire collection is on display in Revolution, with the plan to make the rest available to a worldwide audience through a new web site in March.

"[The museum] will be seen as a destination of important papers and other important artifacts located around the world for that definitive collection point of oral histories of people whose stories need to be recorded," Hollar said.

After being in the Valley for 12 years, why is now the right time to plough $19m into Revolution? According to Hollar, the time is ripe because of the ubiquity of computing online and in our pockets: we need to understand the journey from moving mechanical parts to digitization, from room-sized single-purpose dinosaurs to the multifunction iPhone, from switches and flashing lights to the keyboard and screen.

The entrepreneurs and engineers of Silicon Valley could also learn a thing or two by examining their past. "Some people in Silicon Valley believe they don't look backward, they only look forwards, but some people here who are very successful do understand they are part of something larger," Hollar said.

I hear echoes of British wartime leader Winston Churchill, who was fond of George Santayana's sentiment that those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it. In this case, however, they might also miss new opportunities.

"The Google search engine is based on a very simple analogy that academic articles are known to become authoritative the more they are cited," Hollar said. "By making that analogy, Larry Page working with Brin took search from looking for words on a page to looking for something that's really important to you."

LEO's remaining bits were scooped at auction (photo: Gavin Clarke)

As more and more of the pioneers of modern computing age and pass away - Sir Wilkes died last year, and just one of the ENIAC women remains with us - there must surely be among modern computing's pioneers a growing desire for something tangible that preserves and records their achievements. It would be ironic if those obsessed with digitizing and recording data fail to record their stories, and if those stories slipped into an oral tradition or - worse - a Wikipedia-style group consensus of history where facts are relative and received secondhand. How many more LEOs are alive in the auction houses of the world, waiting to be clawed back?

Was such a concern for legacy behind Gates' donation to the museum?

"I think he's proud of what that little piece of tape represents," Hollar said. "That's the essence of the very first days of Microsoft, and if you talk to Bill and [cofounder] Paul Allen about it they are very aware now they are at a point in their lives where they are very aware that what they did was important and it needs to be preserved.

"I'm very glad they see the museum as the place where they want that to happen."

I just wonder if Gates feels as weird about all this as I did. ®