Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2010/12/07/mcnealy_sun_and_open_source/

McNealy to Ellison: How to duck death by open source

Ex-Sun boss talks code, community, and underpants

Posted in OSes, 7th December 2010 01:30 GMT

Interview Let's forget the last few years ever happened — the last five, at least. Possibly 10. In the 1980s Sun Microsystems was on fire.

Founded in 1982, Sun raked in so much money that it broke the psychologically important $1bn sales barrier in six years. It took Microsoft 15 years to hit $1bn — six if your starting point is the date Microsoft was incorporated. Oracle — up the road from Sun — took 14 years.

Sun was the fastest growing US company between 1985 and 1989, according to Forbes, and supplied the entire US government with more than half its workstations nine years after starting.

Sun was early to the 1980s PC revolution. It built powerful machines that people didn't need to share compute time on, and it did so using off-the-shelf components, and based on SunOS Unix, which was based on Berkeley's BSD from Bill Joy. The BSD code was essentially free to anyone who wanted it. The creation of Berkeley Unix is regarded by some as the "birth" of open source software.

Burning bright: McNealy's Sun sizzled in the 1980s

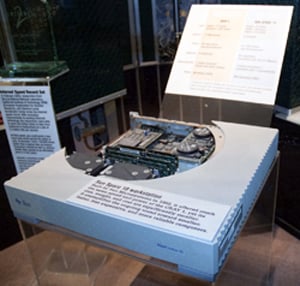

The Sun machines were cheap compared to computers of that time, but not that cheap — and it's easy to see how Sun soon busted the $1bn barrier. The Sun Sparc 10 workstation, 10 years into Sun's life, sold for $40,000. Bill Gates began selling Windows 1.0 at $99 a pop. No wonder Microsoft hit $1bn later in life. Today, $40,000 doesn't buy you a PC, it buys you a super computer with four teraflops of power — the Sparc 10 got you 10 Megaflops.

Still, stars that burn the brightest fade the fastest.

In the nearly 30 years since Sun started, Microsoft sold enough copies of Windows and diversified so broadly that it became the world's largest software company. Oracle became the number-one database supplier. Sun? It stumbled so badly that Oracle swooped in and bought it for a "mere" $5.6bn this year.

In a fitting memorial to the past, you'll now find a Sparc 10 behind glass as an exhibit at the Los Alamos National Laboratory museum in New Mexico. I saw one while on vacation there, right next to a Cray.

If Sun cofounder Scott McNealy has any regrets about the sale after those jet-fuelled early years, it's that he didn't get more of Oracle chief executive Larry Ellison's money for Sun's shareholders. "The week Larry closed the deal we were at the bottom of the Dow — we hadn't been that low for decades," McNealy told The Reg in a recent interview.

Sun was a group effort that became McNealy's charge. Stanford grads McNealy and Vinod Khosla founded Sun with Andy Bechtolsheim, who'd built the first workstations that first attracted McNealy, along with Joy. Khosla and Joy were long-gone by the end, while Bechtolsheim had left, been re-recruited and then slipped away again in 2008.

Having sold Sun to billionaire yacht-racer Ellison, McNealy is now doing unpaid work. He advises startups for no salary or retainer, he sits on the board of Curriki — a project he created to deliver free, open source educational materials for kids in the US up to college age — and he speaks at the odd event, such as last month's PostgreSQL West 2010, where I caught up with him.

McNealy might rue Sun's sale, but — truth be told — he probably had relatively little power over what went down. After a decade of red ink, and with Sun's market cap plummeting $5bn in four months to below $3bn, Sun's largest shareholder — Southeastern Asset Management — decided it was time for action, and they weren't taking any chances. The investors expanded the size of their stake in Sun to secure greater voting rights, and landed two extra bodies on Sun's board to force a strategy Southeastern said would find "opportunities to maximize the value of the company for all shareholders." Translation: sell Sun.

A happy place called MySQL

Further, McNealy was no longer running Sun day-to-day, having become chairman and relinquishing the CEOship to ponytailed vision chief Jonathan Schwartz, with his talk of open sourcing Java and Sun's software, and of floating Sun's business on a "rising tide of opportunity." As one pundit famously pointed out, Schwartz embraced an open source underpants gnome strategy. Immortalized by South Park,Underpants Gnomes sought to collect underpants during phase one and to turn a profit in phase three. Getting from pants to profit was the bit they hadn't worked out.

Towards the end of its life, Sun's open source projects were yielding downloads but no dollars; revenue from Java, open sourced amid great hype in November 2006, was falling, and only Marten Mickos' MySQL, bought by Sun for $1bn in 2008, was growing.

Money from underpants

It couldn't have come at a worse time. Southeastern needed revenue model Plan B at a time when Sun's high-end Solaris server sales dried up in late 2008 as the economy went south. Everybody was suffering, but Sun hadn't recovered from the 2001 crash. Southeastern had no use for a software strategy founded on a theory and that was failing to deliver.

Today, Sun's formerly failing open source software is in Ellison's hands, and Ellison has made it pretty damn clear that open source is there to serve his goal of profit, and not some exercise in corporate self-indulgence. The marching orders are clear: Oracle, not the community, owns Sun's open source projects, therefore Oracle and not the community will run them. Sun's open-source software contains Sun IP that Oracle now owns, so Sun's IP will serve Oracle's greater business interests. Additional time and money spent by Oracle on Sun open source will deliver a return on investment to, you got it, Oracle.

Sun's business plan for open source software in the 2000s

Oracle has trademark ownership, too, so good luck building that level of brand recognition for your MySQL and OpenOffice splinter.

Oracle's strategy is alienating it from those who'd bathed in Sun's collegiate ways.

Is there, then, a teachable moment here? A moment that McNealy can impart to Ellison, given that McNealy is a career-long fan of marrying open source with commerce since he picked up BSD and ran with it in SunOS, and then teamed up with Unix's then-owner AT&T to sink SunOS into Unix System V Release 4 in 1990?

McNealy, after all, likes to boast how Sun donated an "enormous" amount of its R&D to the community, and he identifies Sun as the Red Hat of Berkeley Unix. Any lessons the old dog of open systems can teach the brash database king?

Sure, McNealy tells us: put your shareholders first.

Wait — what? That's the language of Ellison!

"We probably got a little too aggressive near the end and probably open sourced too much and tried too hard to appease the community and tried too hard to share," McNealy said. "You gotta take care of your shareholders or you end up very vulnerable like we got. We were a wonderful acquisition — we got stolen for a song at the bottom of the Dow."

"That's the message," McNealy tells us. "You gotta strike a proper balance between sharing and building the community and then monetizing the work that you do... I think we got the donate part right, I don't think we got the monetize part right.'

Does McNealy then think that Larry is handling MySQL, OpenOffice, OpenSolaris, and Java well? Oracle is throwing its weight around on Java, created by Sun, claiming Google's Android violates Oracle-owned patents, and is claiming ownership of trademarks on MySQL and OpenOffice — a move that prevents others using those names on their forks.

Speaking at PostgreSQL West 2010, McNealy was blunt on where he stands. He believes in patents and copyright law. Ellison is exercising his rights of patent ownership in Java and open source.

"Do I have a problem with Larry Ellison buying Sun? No. That's part of the capitalist system. As soon as we go public we are for sale. Do I have a problem with him exercising his legal IP rights? No. Would it be how I run and operate? No. But I was a good capitalist, he's a great capitalist," McNealy told Pg West 2010 last month.

The right thing

Open sourcers are mourning the loss of Sun and ruing Oracle's subsequent inheritance. Is McNealy surprised about the way things have turned out on Java and Sun's open-source projects?

McNealy deflects. This wasn't a consideration when it came to selling, he explains. His objectives were value for shareholders and as few layoffs as possible. Prior to sale, Sun was in the midst of dumping a fifth of its 33,400-strong workforce as part of a restructuring.

"It was not an issue of can I do the right thing," he said of Java and open source. "We were a public company. There was a legal tender for us, there were bids in from other companies. At that point when you're in play, it's a question of how do you maximize shareholder value and how do you create an environment where the most Sun employees will maintain their jobs — those were the two things I was worried about.

Solaris: the "new" Linux

"One of the issues I had with one of the other suitors was there was a complete overlap in what they did and what we did, and I could see 100 per cent of the Sun employees getting fired," McNealy told us. He didn't name names, but he was referring to IBM's bid for Sun. IBM had competed heavily with Sun for decades on processors, servers, Unix, Java tools, middleware, and open source. There weren't too many areas where they didn't overlap.

"At least with Oracle, they weren't in the hardware business, the operating systems business — the places and spaces where I saw chance for some Sun employees to keep their jobs, and that for me was an important consideration," McNealy said.

McNealy might not regret the act of selling to Oracle rather than IBM, and he might feel open source went too far by the end — but McNealy's biggest mistake? That would be Solaris.

Noorda cut a $90m Unix rights deal with McNealy

Solaris could and would have eaten Linux's business, McNealy believes. The problem was that Sun didn't act fast enough. Sun didn't open source Solaris sooner — OpenSolaris started to release in 2005. Proud of Solaris' technology and performance, McNealy believes now — as he did back in the early 2000s when Linux was taking off — that Solaris is a superior operating system.

What allowed Linux to become established was the openness of the code — Solaris was still closed — with its marriage to x86, a platform more affordable than Sun's Sparc.

"We didn't really make a mistake with Linux or Solaris. We did System V Release 4 [1990] and that really blew the doors off IBM, HP, and DEC Unix by combining AT&T with Berkeley [BSD] SunOS," McNealy said.

"But AT&T forced us to encumber SunOS so it was no longer an open-source operating system, so we went six or seven years not being open source, which hurt us in the open community. It wasn't that we wanted to go closed, it was just AT&T had very last millennium perspectives on open source and they were protecting the source code like it was the corporate jewels."

McNealy decided to act in 1993, just before the only person holding the most influence over the matter prepared to step down from his position of power. Ray Noorda was CEO of Novell, the company that bought the Unix trademark from AT&T along with Unix Systems Laboratories — the AT&T subsidiary formed out of AT&T's Bell Labs. McNealy said he telephoned Noorda, and in the course of a week negotiated a deal that gave Sun rights equivalent to ownership over Unix, and valued at $90m. Noorda left Novell a year later, and Novell transferred the Unix trademark to industry group X/Open whose members included Sun. Rights equivalent to ownership gave Sun more freedom to work with the code.

In a 2003 interview, then–software executive vice president Schwartz told eWeek that Sun paid AT&T to get rights equivalent to ownership — Sun paid $100m, he said. We double-checked this with McNealy, and he is positive: there was an agreement with Novell in 1994. This would make more sense, given it was Novell that retained the Unix trademark.

Patience pays

Sun went on to use its Unix rights to open the code and create OpenSolaris, spending years and millions of dollars to engineer out patents held by various patent holders.

This was step one in making Solaris more accessible to the community. Step two, putting Solaris on x86, proved tougher, and McNealy faced opposition inside his own company from those who'd grown used to the non-x86 hardware at the heart of Sun's business.

Putting Solaris on Intel would take Sun's Unix to people outside of Sun's traditional customer base of high-spending telcos, financial services companies, and government. It might also give these same people a reason to no longer buy Sun's pricey Sparc servers.

"If we'd have just decided to release Solaris on metal instead of shrink wrapped, Solaris on Intel would have been a wild hit and nobody would have done Linux," McNealy told The Reg. "I could have told them: we'll open source Solaris eventually and the only reason they went to Linux was because Solaris wasn't available on Intel."

Yes, we have no Solaris on x86

"We had some execs who kept saying: 'We are not going to do Solaris on Intel.' I said: 'Time out, yes we are'. And they'd say: 'We are not going to do Solaris on Intel' and I'd say: 'Time out, yes we are' until we got rid of them. That was probably bad leadership on my part."

This leads us to the other problem for Sun, Solaris and Intel: Microsoft.

Sun should, McNealy told us, have sold and supported Solaris on its own x86 hardware. Instead, Sun took the fatal decision of outsourcing that role: it placed its trust in OEMs such as Dell to sell and support Sun's Unix on their Intel boxes. Problem was, these were the very same OEMs who, it emerged during the US Department of Justice's (DoJ) antitrust prosecution of Microsoft, had had their arms twisted into offering only Windows with Internet Explorer on PCs or risk losing access to Windows on their machines.

Faded glory: a Sun Sparc 10 as museum artifact

A hard-dealing Microsoft had told OEMs such as Dell how their PCs would look at boot-up, and to make sure Windows was not only prominently branded but was the only operating system offered. The OEMs complied — it just wasn't in their interests to sell or support Solaris anywhere and risk Microsoft's tearing up their Windows licensing agreement.

In 1998 McNealy testified in front of a US Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on whether Microsoft held a monopoly, just ahead of the DoJ's case. He appeared with Bill Gates. McNealy — a fiery capitalist from the Adam Smith school of economics — famously branded Microsoft a monopolist whose control of Windows was killing innovation.

"The only technology I'd rather own than Windows would be English," McNealy told US politicians hearing his testimony. "All of those who use English would have to pay me a couple hundred dollars a year just for the right to speak English. And then I can charge you upgrades when I add new alphabet characters like 'n' and 't.' It would be a wonderful business."

Looking back, McNealy's feels like a Cassandra whose warnings went unheeded — with the fallout hitting his beloved Sun.

"I thought it would be better to let Dell try to sell it [Solaris on x86] but Dell was under strict orders from Intel and Microsoft not to deviate. I said it all back then, and now it's all come out in the court documents and that was hugely damaging to Sun, and they got a slap on the wrists," he said. "I feel good as a company we didn't engage in that. I sleep better at night — but not on a yacht!"

You can't just blame Dell for the failure of Solaris on x86 — Sun shares some of the blame. Remember that version of Solaris for x86? Well, for some reason those execs with whom McNealy had disagreed decided to stop the practice of making a version of Solaris for x86 with Solaris 9, and to just to make the operating system for Sun's Sparc servers instead. The company quickly reversed course following an outcry from loyal users. Solaris 9 for x86 shipped in January 2003, eight months after Solaris 9 for Sparc. It was the first time since 1994 that Solaris on x86 had lagged the version destined for Sun's own servers.

History lessons

History might have been different had Sun open sourced Solaris sooner and delivered its own x86 servers rather than rely on a set of compromised Microsoft partners. It might also have been different had Sun ventured away from hardware sooner and into that other great moneyspinner, the database. Not having a database was Sun's "Achilles leg," McNealy said. "Oracle sucked an enormous amount of life blood out of [Sun] customers because we didn't have a database to compete."

Oh irony, where is thy sting?

Had Sun transitioned sooner to x86 and a more measured form of open source that you could make money on — not the insane sprint it became towards the end of Sun's life — Sun might be alive today. It might be the kind of diversified tech company that Microsoft and Oracle are now.

A businessman in the hippie state of California, McNealy founded Sun on a belief you could make money from open systems — he fused BSD with workstations to scorch the opposition in the 1980s. In the end, it was the making money part of that equation that escaped Sun.

Sun made $200bn during the course of its lifetime doing what it did best: building and selling powerful workstations and servers built on an open core, not by open sourcing its software and hoping for the best. McNealy and Sun made their billions without resorting to the kinds of abusive tactics Microsoft used or becoming infected by Oracle's zero-sum, almighty-dollar competitive ethos.

With that thought in mind, I question just how much McNealy really honors Ellison when he bats around "good" and "great" capitalist. McNealy's a capitalist, sure — while he's never read Atlas Shrugged, McNealy cites its author Ayn Rand as his mentor while he was growing up. Rand is a hero to those on the political right and in business because of her philosophy of individualism, the free market, and personal responsibility.

Yet, McNealy comes across as old-school, fair-play, slightly paternal capitalist versus Ellison's cult of the dollar. McNealy's dad came from the blue-collar American economy — cars, where product was tangible and the rules of combat and competition clear — as a vice president of American Motor Corporation, eventually bought by Chrysler. That had to rub off.

Would McNealy use this experience and what he's learned at Sun to lead another tech company? Jobs are available: Nokia and HP, after all, recently had open CEO spots, while start-ups are always on the hunt for the kind of credibility that "grey eminence" talent lends them.

Don't count on it. "I'm asked daily to be on boards and be CEO, but I'm doing all my little free stuff. I like free right now because I can continue to say what I want to say."

Again with the "free". ®