Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2010/11/30/charles_eicher_computerland_mac_memoir/

How I saved the Macintosh

After getting the idea from a Clamshell Orgy

Posted in Software, 30th November 2010 12:33 GMT

Memoirs of a Salesman Today, Apple seems unstoppable - its new products dominate their markets or create entirely new ones. But there was a time, 20 years ago, when Apple seemed to have lost everything.

In 1984 I was caught in the middle of all this: I was a sales rep for ComputerLand Los Angeles; the top Macintosh salesman at the largest computer store in the world in Apple's largest metropolitan market.

In the mid-1980s, Apple released the products that defined its distinctive market niche in graphics and print production. Twenty-five years later, the Macintosh is still the mainstay of graphics studios, But it is hard to imagine the modest beginnings of the Macintosh desktop publishing tools. Today's designers would barely recognize the early Mac DTP systems. Nor would they understand the excitement over computerized typesetting and graphics.

In the early 1980s, things were changing in design. Designers had always used a wide array of complex tools to produce handmade artwork with machine precision. Work that would take hours by hand could be done in seconds on a computer. When the first Mac shipped in 1984, designers immediately saw the potential in early products like MacPaint.

In 1985 Apple released the LaserWriter with Adobe PostScript, and Aldus released Pagemaker. This combination of software and hardware was customized for professional typesetting and graphics. The enthusiasm of designers is obvious in this Apple promotional video released that year.

This video spoke to designers in their language. Every graphic artist wanted a Mac and a LaserWriter. But the cost was staggering. A basic Mac with Pagemaker would cost around $3500. The LaserWriter cost $6995 - adjusted for inflation, that is about $21,000 in today's dollars.

My corporate customers started buying Mac DTP systems to replace typesetting systems that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. But few individual designers could afford them. I still remember one designer breaking down into tears when told that her $10,000 credit application was declined.

But many designers could afford a Mac without the printer. Graphics "service bureaus" would print your designs on a LaserWriter for 25 cents a page, $2.50 for ultra-high resolution film on a Linotronic imagesetter. Now the print quality of a major publishing house was within the price range of almost any designer.

Apple even had an advantage it didn't realize. Apple hardware engineers were notorious for sneaking in hidden features that nobody noticed - or approved of. One of those features was AppleTalk networking.

The LaserWriter was designed to work over a simple network using telephone cables. An entire office could share a LaserWriter, spreading its cost over a whole office full of Macs. Hewlett-Packard's first LaserJet printers, meanwhile, could only attach to one computer. The networked LaserJets weren't introduced until later.

The Shootout

As Apple's graphics market expanded, so did the array of products - and the prices. It was becoming more difficult to sell such expensive computers.

CEO John Sculley was determined to maximize profits by infiltrating the corporate market, which was probably the only profitable market for such expensive workstations. The IBM PC and inexpensive PC clones were dominant, Apple would have to compete on their turf.

I remember attending a strategy meeting with an Apple engineering executive, who described their new principle of "predictive reaction." It would take two years to produce new computers, so these computers had to be designed to compete with products other companies would release in two years. They had to make a guess as to which of their competitors' products might still be in development, and react to what they would release in the future.

Apple was chasing ghosts, competing with machines that might never exist. Or worse, it was competing with designs from companies that would soon drop out of the PC market, like AST, NEC, and WYSE. And Apple had some serious competition: with Windows, Bill Gates was gunning for the Mac market.

All this should have worried me, but it didn't. Our corporate customers were buying millions of dollars of Macs. Our largest client was Disney - it was very secretive about its purchases, and required us to sign nondisclosure agreements (NDAs), for fear that it would be known they were one of Apple's largest customers. Disney disliked the expense of the new Macs, and was always pressuring us for equivalent PC products at a lower cost. I finally got tired of this battle, so I decided to do a "shootout."

I arranged two roughly equivalent computers, a Mac II and a Compaq 386 with Windows 2.0. and delivered them to the Disney Imagineering studios for a feature-by-feature comparison. But I made a fatal mistake. I demonstrated both machines completely stock, except I added Adobe Type Manager to the Compaq, so it could display WYSIWYG fonts.

In front of a crowd of about a hundred of Disney's top designers and computer people, I showed how the same functions worked on both Windows 2.0 and a Mac. The Mac clearly had the advantage. All the applications worked together seamlessly. On Windows, what you saw was not quite what you got on the printer, and none of the apps worked together without complex workarounds.

After exhaustively demonstrating the Mac's superior qualities, I was stunned by the conclusion of the Disney VP. He said, "wow, thanks for showing us the PC can do everything the Mac can do!" I had inadvertently disrupted a multimillion dollar Mac account.

But Apple wasn't doing much better at demonstrating its own advantages. Its marketing was losing focus. Apple was coasting off the strength of its previous successes, charging high prices for a premium product, confident that nobody could catch it. And customers were defecting.

The Apple Advantage

I was getting pretty tired of fighting an uphill battle to sell Apple products, even though I was successful enough at it. I worked at various ComputerLand locations, helping pump up Mac sales. None of them cared whether their profits came from PCs or Macs, until I showed them there was more profit margin in Macs. Typically PCs sold for a 12 to 15 per cent margin, while I sold Macs at a 20 to 25 per cent margin. Then they got more interested.

But Apple was floundering. Even Apple didn't quite know how to market its products successfully. It tried many different approaches, my favorite being a Laserdisc of Desktop Publishing videos. They were quite professionally produced - Apple could make some pretty amazing videos when it tried.

And I loved the Laserdisc machine. It was interactive - you clicked a menu on the Mac and it would play a segment. I knew how to program this myself, I'd worked with a prototype of this LD player in college, under a grant from IBM. They actually withdrew the grant when they heard we'd hooked it up to an Apple II. I had a little HyperCard program to cue up my favorite segments from the two-hour videodisc set.

Apple expected customers to sit through an hour or two of videos; I just hit the highlights for two minutes at a time, in any order I liked. Customers loved these demos, and so did our Apple reps when they saw what I'd done.

So one day my Apple rep visited me with some news. She said that ComputerLand was planning a contest to see who gave the best Mac demo, and that I should plan to be in it because I would probably win. The prize at stake: $10,000 and a cushy job in marketing at ComputerLand corporate headquarters.

Within a week, I received an invitation to enter a contest called "The Apple Advantage." I had 20 minutes to make any kind of presentation that demonstrated the advantages of Macintosh systems. I had to cover four mandatory points, but other than that, I could do anything I wanted.

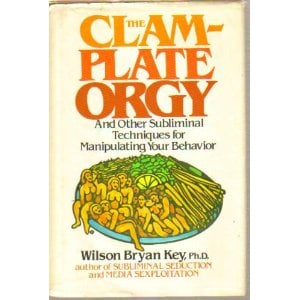

I'd been working with advertising agencies and print studios, so I would demonstrate a new concept, called "multimedia." This was a concept I borrowed from the strangest marketing book ever written. This book exposed the techniques that advertising agencies used to manipulate consumer demand. A consumer will encounter a product's marketing far more often than he encounters the actual product. A company logo like Coke or McDonalds might be seen thousands of times, in multiple media, for each time the product itself was consumed.

So ad agencies specialized in making the corporate image consistent between media. A Coke logo had to look the same in a printed advertisement, on TV, on the side of a vending machine, and on the side of the can. Every time the consumer came in contact with the logo, it was a chance to create positive impression of the product.

Now with the Macintosh, you could project your corporate logo or images into multiple media. That meant print, video, and live presentations. Powerpoint had just been invented, but it was primarily used to create 35mm slides or overhead projector transparencies.

But that was too primitive for my purposes. So I put every technology I knew into that one demo. I had a CD-ROM to play classical music during my introduction and closing. I used a Mac IIx with a special video card that could pass my LaserDisc video on to the screen. I made an elaborate interactive presentation in Macromind Director 2.0, with complex animations, and it would cue up two minute LaserDisc videos to hammer home my main points.

The primary content was how I created a brochure for our ComputerLand Rental division, using Illustrator 88 and Pagemaker, then making Linotronic films and having them printed in a regular print shop. Our brochure was simple, in two colors, but attractive and professional.

Best of all, our rental division brochure featured Apple products on the cover. I was told that eight people would judge my presentation, so I made four sets of materials (they could pair up - the materials were expensive). The presentation sets included the brochure, the films used at the print shop to make the printing plates, printouts of artwork used in the brochure, featuring the Apple and ComputerLand Logos. I even had an actual printing plate used to print the brochure, figuring that I might need to explain the offset printing process.

I had everything fine-tuned and rehearsed. Apple would provide a Mac II and a video projector, but I would would leave nothing to chance. I could not risk running a complex presentation on unknown hardware, so I brought my own Mac IIx system, preconfigured and ready to run the LaserDisc, CD audio, and video projector. I even brought a duplicate copy of my presentation on a hard disk, just in case.

Becoming a Demo-God

Word of my complex presentation had spread at Apple, so I was asked to give my presentation last. As I waited, I couldn't see into the presentation room (no peeking at competitors!) but during breaks, I could see that there were only eight judges, as expected.

Then it was my turn. I rolled in with my cart of gear, and immediately ran into a roadblock. They would not let me hook up my Mac. I had to use their Mac II, a slower machine than mine, and no special video card. I could not put my LaserDisc videos onto the projector, I would have to show them on a separate monitor. The seamless transitions between my presentation and the videos made for one of my best effects, but I would have to do without.

As I set up, I distributed my materials to the judges, and noticed the room was now filled to capacity. I recognized some of the audience as senior Apple and ComputerLand corporate executives. There is a video camera recording me - it wasn't there for the other presentations. This will have to be my best demo ever.

I launch the demo. The ComputerLand logo slides down onto the screen, and for a little extra pizzazz, I had an animation that made the Apple logo spin once. But I immediately notice a problem, the animations are running slower than expected. Oh no, I realised - this is a Mac II. It is slower than my IIx. My presentation timing is all ruined.

Nothing I can do about it. I run through all my points, and the audience is amazed at the concept of a consistent corporate image across different media. Better yet, they are seeing it live, as the Apple and ComputerLand logos appear on videos, on the projection screen, on laser printed documents, and professionally printed brochures, as I present the Apple technologies used to produce all these items.

I am deconstructing my presentation, at the same time I am presenting it. It is a presentation about how I produced this presentation. The audience is blown away. But I am about to be blown away.

My 20 minutes are up, and I still have two minutes left to go, my grand finale. I apologize for running long and bash forward. Finale, fade out to classical music on CD, big applause, hooray it is a huge success. Unfortunately, one of the judges comes up to inform me that technically I have been disqualified for running over 20 minutes, but my presentation was so impressive that they will try to give me a break.

An Apple executive comes over and asks me how I got the Apple logo to spin. I explained the technical details, and he says, "That was amazing. Now don't you EVER do that again. You just DON'T mess with the logo!"

Another Apple exec asks me if I created all this presentation myself. I said I did the animations, the brochure design, everything by myself except for four minutes of video produced by Apple. Then he asked, "You even did the music?" Oh, maybe not.

"No, that was a CD of a Vivaldi string quartet, but I think I could play the cello part." He laughed.

Two weeks later, I received a telegram (yes, telegram!) announcing the winners. I was awarded a Honorable Mention and $500. I guess those two extra minutes cost me dearly.

Later in the day, my Apple rep comes in to congratulate me and say how happy everyone was with my presentation, and how she'd fought to keep me from being totally disqualified but the Honorable Mention was the best she could do. I was not in the mood to hear this from her of all people. I told her I'd spent more than $500 on a new suit for this presentation. She cheerily said, "well then, you got a new suit out of this!"

But my presentation would live on. Apple asked me to give the presentation to a national customer, RR Donnelly, the Yellow Pages company, the largest producer of printed material in the world. It was trying to decide on outfitting its entire corporate print production on Macs over the next two years, an investment of millions of dollars.

I first met with them to discuss their proposed purchases, outlined some pricing, then gave my presentation. Afterwards, they were quite certain they could justify their Mac purchases. I tried to close the deal, asking when I could expect their first order. The response stunned me, "oh we do all our orders through ComputerLand of Houston." That was our arch-rival, the second largest computer store in the world.

My presentation continued to live on, on and on.

A few months later, I received my quarterly packet of new marketing materials. It contained store displays for a totally new campaign, "Apple Desktop Media." Apple paid an advertising agency to produce a national ad campaign in print, on video, even radio.

Apple would send out thousands of promotional videotapes to drive customers to our stores. We would show them an elaborate Macromind Director presentation on CD-ROM, accompanied by materials from a book with illustrations, color sample brochures, and even 35mm slides, all demonstrating a consistent image through all the different media, on screen, print, and video. This is my presentation, but modified beyond all recognition by an expensive ad agency. This would become Apple's most notorious campaign, known as the "Helocar."

Here is the videotape that Apple mailed to customers. It begins with an extended version of the TV commercial that ran nationwide for weeks.

I can understand the reasoning for the Helocar; Apple had to pick an obviously nonexistent product. It couldn't let a real product interfere with its message. I was even amused that my spinning red Apple logo had become a spinning red Helocar. But the Helocar overpowered the message. People did not understand what they were watching on the commercial - some thought it was an advertisement for a real helocar. Nobody seemed to understand it was an Apple ad.

The rest of the video was even more confusing. Corporate clients that received the videotape didn't understand what it was selling. Apple was marketing some of its most nebulous products, like HyperCard.

There is a long segment showing a storyboard for a TV commercial with Wilford Brimley, produced in HyperCard. TV producers came in to my store asking for this storyboard software, and I had to explain it was a do-it-yourself project in HyperCard. I showed them how to do it, and they would just not understand, and walk out of the store in confusion, wondering why didn't I have this magic storyboard software. I hesitate to think of what would have happened if they had tried to market Macromind Director, one of the most complex applications I had ever used.

Goodbye, Helocar

After seeing my presentation turned into a marketing disaster, it was becoming obvious I was wasting my time in computer sales. Apple was unable to clearly define and market its own advantages. I helped shape the market and entrench the Mac in the largest corporate accounts in America. But the era of full-service computer stores was coming to an end. ComputerLand faced increased pressure from competitors like BusinessLand, just as Apple faced increasing competition from Microsoft. It was getting harder to make a living selling computers, and ComputerLand merged with another company and I was made redundant, merged out of a job. I changed careers and went to work in one of LA's best graphics service bureaus. It was where I really belonged. By the time Apple straightened out its multimedia marketing in the early 1990s, I had returned to Art School, where every student wanted to become a computer artist - except me. ®

Charles Eicher is an artist and multimedia producer in the American Midwest. He has a special interest in intellectual property rights in the Arts and Humanities. He writes at the Disinfotainment weblog.