Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2010/11/29/symbian_history_part_two_ui_wars/

Symbian's Secret History: The battle for the company's soul

How Nokia took charge, and never let go

Posted in Networks, 29th November 2010 13:24 GMT

Part Two This is Part Two of a special report about the formation and early years of Symbian. It contains stories and plans that have never previously come to light. Part One dealt with the formation of the venture. Here’s the main course: how the decisions taken between 1999 and 2001 shaped not just the future of Symbian, but the course of the mobile industry over the next decade.

Let's rejoin the story on launch day.

On a brilliantly sunny June day in London, 130 Psion Software staff arrived at work and found they had a new employer, with an unfamiliar name. Most had been completely unaware of the development.

The day before, they had been working at a tiny company, trying to crack into new markets dominated by giants. Now they learned that the mobile industry's giants had entrusted their futures to them. And Epoc, the operating system that had been put on life support three months earlier, now looked to have a boundless future. They were now at the centre of the fastest growing, wealthiest sector of the technology industry.

It was the start of an intoxicating time. Two years later, Symbian would reach a valuation of £11bn, by some estimates, and be cited as the most important technology company on the planet. It seemed to be a new kind of business, and a validation of the European model of competition based on co-operation at deep technical levels, the model that had created the GSM mobile success story.

Symbian owned the future. Or so it seemed.

Yet Symbian would not ship a mass market product for four years. By then, many of the visionaries who founded the company had departed, and Symbian - while validating the original idea - had become very different to the original dream. Thanks to never-before-seen designs, and the recollections of many of the executives involved, this story for the first time explains how this happened.

The world reacts

Symbian sprang into life with two levels of management, representing operational management and owners. The operational board was led by CEO Colly Myers, with an all-Psion team of Stephen Randall, Juha Christensen, David Wood and Bill Batchelor, who had led the Series 5 project. Later, Thomas Chambers joined as CFO and Kent Eriksson came on board too. Psion CEO David Potter acted as non-executive chairman of the owner’s board.

So the Symbian management had an all-Psion operational board, but a Psion-free company board. It's not such an unusual arrangement. What made it unique is that the company board were all customers of the people they managed. This was to cause enormous tensions, as we'll see.

It meant that getting everybody rowing in the same direction was difficult. The customer-owners could collude to make decisions over the heads of the operational staff, or behind closed doors, and then enforce them from on high.

Still, the early days were promising. The dominoes just seemed to fall into place remarkably quickly. Former Symbian executives say they made a conscious decision to attract licensees, rather than ship product, to give the venture momentum – by stopping them signing with Microsoft. By October, Motorola had formally confirmed its membership. Japanese giant Matsushita joined in the following May. Symbian had a very public royalty structure - £5 for a smartphone, £10 for a communicator - and vowed to keep this for all comers, no matter how small or inexperienced.

Palm responded with a sniffy press release, describing it as a "concept without customers". Bill Gates fumed in private. Two memos (a year apart) that subsequently surfaced show that the Microsoft founder perceived Symbian as a personal snub - and issued a range of responses... some rational, some less so.

Psion’s share price rocketed, with analysts valuing Symbian at £4bn.

“The second tier companies assumed the first tier companies must have done their due diligence. Within a year we had 80 per cent of the market,” Randall recalls. That was the existing market – the new market, for which Symbian was created, didn’t yet exist.

The operational board of former Psion execs had a fairly clear idea of what Symbian needed to do: to achieve goals that the members couldn’t do individually, or together by other means. But beneath the surface, there were hints that the different shareholder companies had different ideas.

Symbian was set up to create something that didn’t exist: a mass market for smartphones and mobile data devices. These needed slick user interfaces and applications. For developers, the experience of coding for Epoc was a challenge. It was full of peculiarities and ingenious hacks – but developers used to slick Microsoft or Borland tools expected something better.

Symbian’s operational board identified a company that could help. A Canadian outfit Metrowerks had helped saved Apple in its transition to Power PC chips a few years before, and had created a developer friendly IDE called CodeWarrior.

But the Symbian executive board, comprised of the shareholders, vetoed the idea. Former executives say Nokia wielded the veto. Metrowerks was snapped up by Motorola.

The war over the UI

The user interface issue became the most hotly contested topic at Symbian. CEO Colly Myers said that successful Symbian devices must have the “enchantment” factor – explicitly recognising the importance of user experience, and high product design values. Twelve years on, this is universally recognized.

But it was harder to put into practice.

On Symbian’s launch day, Myers spoke of a desire to create several device “families”, and said there may be between “five or eight”. He stressed the new company's philosophy was flexible. Unlike Microsoft, Symbian would encourage licensees to innovate and customise on top of these. He was sincere – it was a cornerstone of the venture, and without the assurance, Symbian would never have coalesced.

There were practical reasons to keep the number of “device families” small. Developers prefer a small number of build targets for which to design their applications. Make too many, and the administration and support burden for a developer multiplies exponentially. Application developers can’t use a specific button or key shortcut, for example, if they're not sure it's going to be there.

Today, former VP of technology at Symbian Simon East is developing iPhone applications and finds it remarkable that Apple has just one build target for four generations of iPhones, iPod Touches, and even the iPad. But then Apple licenses its software to no one.

So how many "families" was too many?

Family fortunes

Apple star designer Scott Jenson, now at Google, joined the Symbian design team in 1998. Jenson was an Apple human interface alumni who had sketched out the original Newton and stayed with the product to launch. His hire showed that Symbian was the hottest ticket in town for talent.

“Between Juha [Christensen] and Scott and Nick [Healey] we maybe arrogantly came up with this idea that four UIs could cover the whole universe of mobile devices” says Randall.

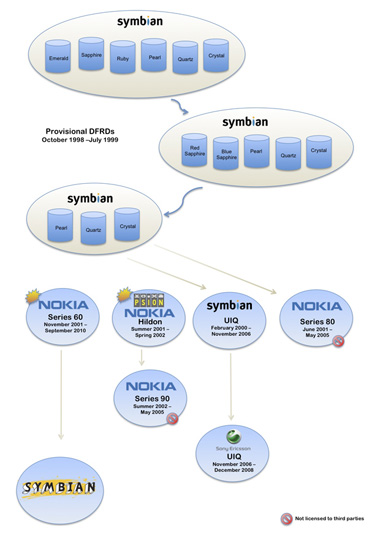

The Design team found themselves grappling with six "device reference family designs", or DFRDs, each named after a gemstone.

Jenson never thought it was realistic idea, he says. Right away, it was obvious that "family" meant different things to different people. The DFRDs were a strange collection of promising, ground-up designs and hopeful submissions from Symbian’s owners.

Two designs came from the Symbian team. Symbian acquired Ericsson’s design lab in Ronneby, Sweden and with it, a new and promising pen-based user interface, which became Quartz. Symbian’s design team were also working on a fresh one-handed soft key design, called Pearl.

Three other DRFDs (Ruby, Sapphire and Emerald - later boiled down to two, Red Sapphire and Green Sapphire) were manufacturers' ideal version of what they thought a softkey phone should look like - with a heavy manufacturer bias. Here, “family” meant “resemblance to something we do today".

There was also a design for a QWERTY communicator – not surprisingly, from Nokia.

Between April and June 1999 furious discussions took place. Motorola, as the former Psion staff had feared, said no to everything.

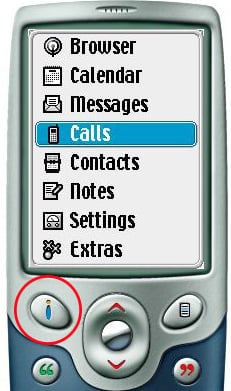

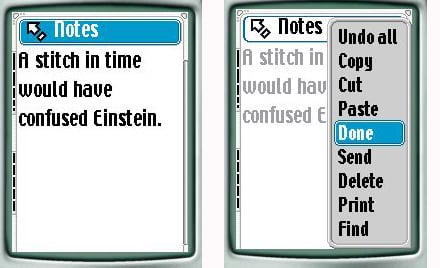

"The design team wanted Pearl, with no shitty legacy UI features," recalls one former executive. Pearl could work on the smallest handset, but ‘degrade up’ to handle any kind of screen variation. Here is it what it looked like. The story continues below the box out.

Symbian's Pearl UI

Pearl's home screen

The i key always overlays the main menu

Menu actions

No "back" key is necessary. You navigate out of the running app by heading for the top.

Context menus in action

Then, finally, there were three. Pearl (announced here) had subsumed all the other one-handed softkey designs. Quartz was the pen-based UI. And Nokia had steered its QWERTY keyboard design through the discussions – this became Crystal.

Bit by bit, it became apparent that Crystal (unveiling reported here) was not like the others. Nokia had ensured Crystal would look and feel like Nokia’s proprietary Communicators look and feel. Nokia would never share the design with anyone else. If somebody wanted to license Crystal, they would have to deal with Nokia, which had built up an arsenal of patents on the Communicator concept.

“Crystal was never a DFRD but just a subcontract,” says Jenson. “Nokia was brilliant an manipulating Symbian, getting them to do what they wanted. This wasn't nefarious by any means, but just good business.”

This would become the basis for Symbian's first true smartphone, the ‘Linda’ project from 1997 finally bearing fruit in the Nokia 9200 four and half years after the deal was struck. It was the most technically challenging, too.

“It was a complete ruse to call Ruby, Sapphire or Emerald DFRDs as they were just trying to follow the Crystal model, to get Symbian to make a custom platform for them,” recalls Jenson today.

But executives noticed something stranger. Nokia was cooling on the idea of UIs altogether.

Nokia fights back

For the man who’d drawn up the Symbian business plan, the goal was simple.

“We would own the UI. If you own the user experience, you own the developers, and you find a lot of valuable stuff is migrating to you,” says Christensen.

But if the former Psion staff, familiar with driving radical and popular designs to market, thought that Symbian was just Psion Software with a bigger toy box, they soon realised they were at a very different kind of company.

“We started seeing signals,” says an executive present at strategy meetings.

Meetings dragged on without conclusion. Decisions were delayed. Ericsson, under subtle influence from Nokia, also began to cool on the idea of accepting designs from Symbian. And all for products which didn’t exist.

“Our ability to dictate the UIs was certainly removed very early on in the negotiations,” East recalls.

“It became clear to us that Nokia had woken up to the fact that if these guys own the UI and the developer model - then that's where the value is going to migrate to.”

Despite assembling a design team to create great UIs, only one Pearl remained.

(Inaudible)

One of the strangest beliefs circulating in the industry 10 years ago was that Bill Gates refused to allow Microsoft employees to mention the name Symbian. Your reporter had a hand in creating this myth.

In September 2000, one of the architects of Symbian Juha Christensen made his first public appearance in his new job as Microsoft's VP of Sales for mobile products. He had been on gardening leave since leaving Symbian in March. The transcriber couldn't glean the name of his former employer, so whenever Symbian was mentioned, the transcription inserted "(inaudible)".

Never wanting to let a misfortune leave without fulfilling its comic potential, we left open the possibility that this was censorship from on high. On several occasions subsequently, much to the (understandable) annoyance of Symbian comms staff, we decided to play along.

"I looked into this," he tells us. "It was just a transcription error. We grow up in Europe on Monty Python, but one thing you learn about big American companies, is that the sense of humour is pretty non-existent"

“We thought it was wonderful - but none of the licensees wanted to buy it,” said one executive.

"Nokia was masterful at influencing people. Ericsson willingly went along, but they should have known better," says Christensen.

“They decided internally that was not going to happen. Without telling us. They started talking about migrating UIs from Symbian.”

Psion design veteran Nick Healey (as he vividly described in this 2007 interview) had already lost faith. There were too many compromises by committee. He left after eight months.

Nokia certainly wasn’t trying to capsize Symbian, veterans agree. Nokia was its strongest supporter, and had the religion about licensing – about creating a mass market. It is the strongest, only supporter today.

Another factor that’s easy to overlook today influenced the many Symbian stakeholders.

Like the music industry, the mobile industry veers as a pack between one business fashion and the next. But Nokia was alone in providing consistency.

Nokia was executing flawlessly. It had overtaken Ericsson as the number one digital mobile phone vendor in the year Symbian was born. Randall remembers seeing “Nokia hitting three year roadmaps to the day”. Nokia’s confidence about user interface design awed, and perhaps cowed, the other shareholders.

“It wasn’t explicitly killed, but it slowly extinguished over a period of time,” says Simon East.

The subtle shift wasn't apparent to everyone at Symbian. The company had developed a technical consultancy, and this was creating the products bu working closely with the customers. The UIs were being developed on the hoof. It became a vital revenue source for Symbian.

"It's the classic model of developing something really complicated, then selling support back to the customer," says one former executive.

But this meant the DFRDs were redundant. They were superseded by the works-in-progress.

Then came a bolt from the blue. Nokia had secretly developed its own user interface. It called it Series 60, and Pearl was redundant.

“They kept it secret from us until it was presented to us very late in the day, a fait accompli.”

Another recalls:

“S60 flat out came in and killed Pearl. It was a threat to Nokia's plans and they didn't want competition. It was that simple. I was told this directly by a senior VP,” recalls an executive.

The long, long haul to ship a product

It took four years before Symbian appeared in a mass market smartphone, the Nokia 7650. Only two other models appeared during that lacuna, a monochrome device from Ericsson which didn't accept third party applications, and Nokia's third Communicator, the Linda project signed in January 1997.

Why did it take so long? Certainly the press played its part in raising expectations to fever pitch.

One reckless journalist described this, “the initial trickle of EPOC devices, led by Ericsson's R380 smartphone, is expected to soon become a flood, with more than 30 devices available in the next 12 to 18 months.” Six months later, Symbian still insisted a slew of products would be hitting the market, from early 2001 on.

A joint venture between Motorola and Psion, based on Quartz and codenamed Odin, was eagerly anticipated. Nokia had earmarked its first mass market Symbian phone to appear in Summer 2001 too. Ericsson has shown an impressive, pen based smartphone using Quartz, and even Sanyo had demonstrated a Quartz device. Yet just one Symbian smartphone would appear in the next 18 months – the Communicator. Nokia's "Calypso", featuring Nokia’s own UI, only reached market in August 2002. Competitors made much of Symbian's difficulties. Wasn't this what you'd expect, they pointed out, from a European-led design-by-committee approach?

So what really happened?

Various reasons have been put forward over the years: the market wasn’t ready, the silicon wasn’t mature, or the networks weren’t in place. Executives cite several others here. Some are interlocking reasons and few are mutually exclusive.

The reality that hit both Symbian engineers and their customers building the phones was that putting Epoc into a complex communication product was much harder than people realised. In particular, moving the OS to new, custom hardware – a job called "base porting" - was problematic. There was no market of standard off-the-shelf integrated components, as there is for smartphone manufacturers today - although this would rapidly evolve. In a couple of cases, such as Motorola's MCore and the processor for Ericsson's first R380, the chip had no MMU (memory management unit).

So base porting was truly virgin territory - and because the phones were an order of magnitude more sophisticated than anything on the market, their complexity added more issues. This may seem so obvious in retrospect, it's almost a tautology. Yet we forget how relatively crude the hardware was then - it was striking in researching this article how much we take for granted.

Base porting was always going to be a challenge, then. But it was additionally problematic, according to senior Symbian staff, because the Symbian partners couldn’t agree who should do it.

“Nokia and Ericsson told Symbian that we should leave that task to them. So Symbian OS always had holes at that level,” recalls one former executive. “Over time, these holes caused more and more problems to new licensees - and even to the old ones. In retrospect, this may have been the single worst decision about the design of Symbian OS.”

Another reason was that the silicon was genuinely immature. Symbian engineers spent many man years of work coding around bugs in the chips. (See: Waiter - these chips are undercooked).

Delays tended to cause more delays.

Against this background was a dramatic realignment of the industry. The telecomms bubble had burst, impacting companies across the industry. The phone manufacturers biggest customers, the operators, had badly miscalculated the appeal of WAP - then paid billions for 3G licences. Three of Symbian's big four shareholders - including Ericsson and Nokia - were large suppliers of telecomms equipment to the operators, as well as suppliers of handsets. Ericsson also experienced a dramatic fall, and spun out its handset business into a partnership with Sony in 2001. For all its consumer electronics know how, and clever designs, Sony had failed to make any headway with its GSM handsets. None of these moves made customers look at their risky, expensive Symbian smartphone projects with confidence.

Much of the delay in this period can be explained by manufacturers failing to bring projects to market - there was no shortage of activity. Sony had invested in a Symbian phone with a 3D display that impressed all who saw it - but it never reached the stores. Panasonic never brought its smartphone to market, and only ever offered a couple of lacklustre models much later in 2005. Kenwood's phone was also canned.

Once initial targets were missed, the major shareholders insisted upon introducing micro-management, which also slowed progress further. Measuring and monitoring, as in any bureaucracy or company lacking leadership, had displaced development as the focus.

Milestone or Millstones?

One decision that was hotly contested was Symbian's decision to deliver regular milestone releases every six months. This was supposed to assure customers that the new venture was a dependable supplier. But it had several consequences.

"Releases bore no relation to the phone manufacturer's schedules. So releases would be made that nobody wanted because either everyone was busy making a phone on the last release or they weren't ready to start a new phone yet. Some releases simply disappeared because they had no customers," notes a senior engineer.

Phone manufacturers wanted the new features in the older stable versions they were working with, so the features would have to be backported - an unpopular job at Symbian. Sometimes milestone releases had to drop almost everything that had been promised. And with a distant window, the engineers went crazy in the sandpit.

"It gave carte blanche to the software engineering teams to just go away and break everything after each release, because they didn't have to have a complete working system until 6 months in the future," he adds.

Today we see the prolem hasn't really gone away. Phone manufacturers chafe at Google's impressive, rapid release schedule for Android - and insist on backporting features to their older stable versions.

As the UI air wars took place, back on the ground Symbian gradually became a custom product design house, working closely with the owner/partners to bring the phones to market. In the early years revenues from consulting far exceeded revenues from royalties. (Royalty revenues actually fell in 2001).

"The feeling at one point was that Symbian couldn’t deliver anything, that nothing was going to come out of it,” recalls Gretton, who had built up Psion’s software team from scratch after Symbian was formed. “The computer side got so frustrated we considered using alternative OSes."

And this in turn, impacted Symbian’s bid to continue its UI work.

"In the middle of this period", recalls a senior engineer, "the tech bubble burst. And suddenly all the limitless money that Symbian management had been promising (and people in the company had been spending) dried up. Nokia had wanted its "Calypso" phone, the 7650, on the market by the middle of 2001. It cranked up the pressure, and having thrown so much into its own user interface, quietly decided it wanted to renegotiate one of the untouchables of the Symbian agreement - the royalty schedule.

Roger Nolan, who set up Symbian’s technical consulting operation, recalls:

"Nokia decided that 'you're having trouble delivering the base stuff - what are you doing with this other stuff?'"

He remembers one executive board member from a large Nordic handset manufacturer banging the table during a meeting, shouting:

"We gave you the fucking money, now give us the fucking software."

Waiter - these chips are undercooked

What does an engineer do when the erratum sheet to a chip is longer than the chip's technical reference manual? Most would be tempted to slip quietly out of fire exit, and not start screaming until they'd reached the car park. But this kind of problem faced Symbian engineers daily as they grappled with immature and poorly documented silicon.

"There was a fundamental difference in outlook," recalls one former Symbian engineer, who was faced with making the OS work on new and foreign hardware for its phone makers.

"When Symbian said 'reference', it meant product-quality, something that you could take and use in a phone and then add to. By 'reference' the semiconductor companies (semicos) had always meant something rough and ready that was just enough to demonstrate the principles of getting the hardware to do something, you were supposed to use it as a guide to creating a proper version.

"Semicos like Texas Instruments were happy with something that just booted and showed off the headline features of the chip, such as video playback. They didn't care about finishing it to product quality, or filling all the holes, or supporting it, or making it portable - to them that was stuff that their customers were supposed to do."

Few chip companies were even interested in a market that didn't exist, but one that was - and later reaped the reward - was Texas Instruments. TI supplied custom chips to Nokia, while Ericsson designed its own, and had a close relationship with VLSI, which had recently been acquired by Philips. For much of this period, Ericsson came out better.

"TI had decided to save money by designing their own data cache instead of licensing the ARM one," he recalls. "So none of the revisions of the OMAP 15xx that were delivered ever had a reliable data cache. On the same chips, the technical reference section on the built-in real-time clock advised you not to use it because it used too much power."

Ericsson would sell its semiconductor business off in 2002, but continued to design its own silicon with VLSI (now Philips). The NX processors it designed for its P800 phone, up to its P1i, were very efficient - and relatively clean.

Nightingale: a tactical retreat

"Nokia thought they’d created a monster – now let's take it away,” says Christensen.

Nokia succeeded in crushing the Symbian UI vision, but not everyone attributes nefarious motives to the Finnish giant.

“Nokia’s vision of the future was as sound as anybody could predict. So as soon as we lost our battle for the UI, all the others went back to their flavour of week kind of thing,” Randall remembers.

"I don't think anyone was being dishonest. We didn't realise how controlling Nokia would be, when push came to shove," says Roger Nolan, who managed the Symbian technical consulting operation. "A lot of the time the board that were running the company [the Operations Board] thought they had a lot more autonomy than they did."

Another Psion designer, Matt Millar, says the politics hampered the vision.

“Symbian knew what consumers wanted, what software they wanted. But it got pulled apart by competing views – it could never execute on Symbian view.”

Symbian board sounded a tactical retreat from user interfaces - codenamed Nightingale.

"We were having difficulty staffing all the licensee projects. Only Quartz and Crystal survived as living code as UIQ and Crystal respectively," Nolan remembers.

Symbian and Nokia agreed to allow a startup - Matt Millar's Mobile Innovations - to take control of Crystal and consult on the forthcoming Nokia Communicator.

"Of course, it was tactical for Symbian but strategic for Nokia - they ensured that they were the only people who could cheaply produce Symbian phones."

Nightingale was a landmark decision – it ensured that while Symbian would remain a powerful industry force, it wouldn’t set the agenda. Most now see it as inevitable – but not everyone. Christensen today believes a more entrepreneurial Symbian would have called Nokia’s bluff, and gone outside the club of original owners for investment.

“Where would Nokia have got another OS from?”

After Nightingale, Symbian could never quite decide whether it should keep a foot in the business of designing and licensing UIs. It sought to spin out Quartz as a joint venture, jointly owned by Sony Ericsson (as it had become) and Motorola, but CEO David Levin pulled it back in, allowing it to continue as an independent subsidiary. And so it did, until Sony Ericsson acquired it in 2006.

It’s no fun here: inside the Matrix

Symbian’s changed dramatically from the can-do culture of Psion Software.

Within a few weeks, Randall had moved to be VP of Design, and Ericsson’s Kent Eriksson assumed operations.

“We brought in Kent Eriksson to run things. From being an argumentative culture, we had a Swedish guy coming in and running it as a factory – we had a matrix management," recalls Randall.

"Suddenly we were a grown up business. Pragmatically we realised it had to happen, but it wasn't an enjoyable process. It started to be a little less fun."

Symbian rapidly grew from 130 staff to 800.

Psion had traditionally recruited brilliant problem solvers – often from the natural sciences, mathematics, or practical electronics fields such as audio engineering. A degree wasn’t necessary, nor was a familiarity with Psion, or even computing. This changed.

“As Symbian [became] increasingly Nokia's company it got pushed to hire lots of graduates, and moved away from hiring real scientists with real brains, to graduates with some Symbian experience. The product-driven creative people left,” recalls one.

One product manager, who was working on a vital product for a large Nordic manufacturer and shareholder, recalls being ticked off for running up a monthly phone bill of £1,200.

“Yet the customer was billing me at a day rate of about £2,000. I thought, ‘I’m not having this conversation’.”

Another executive recalls getting into trouble for “daring to suggest that WAP was a folly, and was doomed. I was hauled in front of various people and told to toe the line,” he remembers.

High pressure

The pressure mounted on the father of the OS, Psion visionary Colly Myers. He sustained a year of hostile executive board meetings, until Nokia forced its way, according to executives.

"It was no fun being in the senior management team. The supervisory board constantly overruled the CEO; they removed his ability to run the company,” Simon East remembers.

What was Symbian worth?

Symbian would never make a public share offering - a move which would have given the venture real independence. Not surprisingly, Nokia consistently vetoed an IPO.

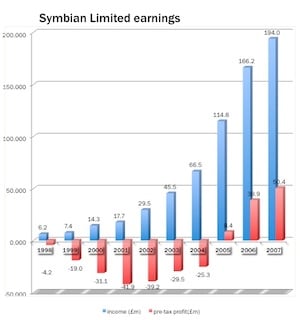

During a decade the value of the private company fluctuated dramatically. The original valuation by Randall and his team - and Goldman Sachs - was £100m. It had risen slightly when Motorola formally took up equity, buying 23.1 per cent of Symbian for £28.75m

Yet at the height of the 2000 bubble, analysts valued Symbian at £4bn, based on an extrapolation of Psion's 31 per cent stake. Staff made their own calculations, putting the value even higher. The logic here was an examination of P/E from the company most like Symbian, which was reckoned to be ARM. At one point, according to this calculation, Symbian was worth £11bn. In June 2000 Symbian said it wished to IPO on NASDAQ.

Symbian didn't float, and the bubble valuations didn't last. In April 2002, Samsung bought a 5 per cent stake for €22m, valuing it at £268m. In February 2003, Samsung bought 5 per cent for £17m, placing the value at £340m. In December that year, Merrill Lynch offered a figure of £240m.

Two months later, Psion proposed selling its stake in its entirety to Nokia , sparking a shareholder rebellion. This threw up some fascinating background material, now forgotten, where Psion chairman Potter hinted at deep shareholder disagreement, and disclosed another doomed attempt to take Symbian public. After some canny footwork from Symbian CEO Levin, three other shareholders pre-empted the deal, increasing their stakes.

Nokia acquired control of Symbian in 2008. The year-end balance sheet showed accumulated losses of £159m, although the company had been generating fast-growing pre-tax profits since 2005. The final net book value recorded was £64.6m.

“The politics got really, really annoying,” he adds. “I couldn’t see how we could do anything innovative. They'd be swooped upon and done by the licensees."

Nick Healey had left in 1999. East left in February 2000. Juha Christensen the following month. Scott Jenson left in July 2001 after Nokia killed Symbian’s only home-brewed UI design, Pearl. Randall left for personal reasons the same year.

Most controversially, Christensen joined arch-competitor Microsoft, leading to Psion pursuing a High Court action to enforce his contractual gardening leave. CEO Myers put a positive spin on it when interviewed in June 2000: "Well, obviously he knows a lot about our plans. We've put him on gardening leave for six months and say, well in six months our products will be on the market and the world will have moved on."

"Nokia is annexing this country, we thought", remembers Christensen. "The other neighbours are willingly accepting it. To us that was insane. Once that happened there was no turning back."

"I like Colly and felt bad about putting him in this position. I still feel bad about it today," he recalls.

Myers himself left suddenly in February 2002, shortly after a particularly tumultuous period - the capture of the UIs by Nokia and its decision to license Series 60, and the vexed issue of renegotiating the licence fees. Symbian wanted code - Nokia wanted to pay lower royalties.

The first mass market Symbian smartphone only emerged in the summer of 2002, four years after the venture set sail. This was the Nokia 7650, based on Nokia’s paint-still-wet Series 60 user interface. Still, the second phone was delivered speedier than the first, and by 2003 a number of products were hitting the market, including Nokia’s game console, the ill-fated N-Gage, and two Sony Ericsson Quartz phones within a year. The first was impressive, the second, the P900 was a dramatic improvement, and was a critical and popular success. Samsung and Siemens joined that year. Despite Series 60, and with a far more defined role, Symbian was back on track.

What happened next?

Much of Symbian's recent history is familiar to readers, and beyond the scope of this article, which looks at formative decisions between 1998 and 2001. After the release of Nokia's 7650 - the first real "Symbian smartphone" in 2002, the system gained increasing momentum. It was no longer a "platform" - but Symbian remained a formidable base system, particularly after the EKA2 kernel revision, and the company was established as the leading consulting and development house for smartphones. Symbian's momentum was driven by Nokia, and a clutch of Japanese manufacturers such as Fujitsu, Sharp and Mitsubishi, who took the Symbian OS kernel and some frameworks, and developed their own UIs on top, as specified by their Japanese carrier customers. The latter devices were never marketed outside Japan, making their sales figures particularly impressive.

The other shareholders were much more tentative. Sony Ericsson released two Quartz-derived devices in 2003, the second of which is widely regarded as the best Symbian smartphone - the P900. But Sony Ericsson focussed instead on its feature phones, to great success, until 2008; its Symbian "flagship" was never joined by a fleet. Panasonic would not release a Symbian phone until a couple of lacklustre models in the mid-00's. Motorola released a couple of devices, sold its Symbian stake in 2003, but then resumed licensing in 2006. Siemens released just one Symbian handset. Samsung was even less committed than Sony Ericsson, and only a handful of devices ever reached Europe.

So Nokia dominated the market share outside Japan, and released dozens of Symbian phones, successfully integrating the components into its "software factory". But Nokia never succeeded in creating a mass market for smartphone applications or content, which arrived in the wake of the iPhone. In 2008, Nokia bought Symbian outright, and licensed both the Symbian code and its own Series 60 (now S60) code to all-comers for free under an open source licence, to be managed by a Foundation. But Nokia had neglected the smartphone user interface for years, and the move failed to win new licensees. Nokia dissolved the Foundation last month. The future licensing conditions for the source code remain uncertain.

Could Symbian have led the industry?

This has been a very different story to write and research than my exploration of Psion. Psion pulled out of a market it created quite dramatically, and recriminations still fly. I interviewed many key executives for these articles and it was hard to find blame being apportioned here. Symbian, by contrast to Psion, has shipped in some 400 million handsets, which is the kind of "failure" many companies would wish to have. But Symbian's role has been one of an important component supplier rather than industry leader, as the team originally envisaged. And since 2001 its fortunes have been tied to one company - Nokia - which last year declared that a Linux-based system rather than Symbian would be its high-end future platform of choice. It was not Nokia, but Apple that eventually created markets for mobile applications and rich content.

“I don’t buy that Symbian is successful today. Most people don’t use it as a smartphone OS and don’t use the smart features,” says East.

Could Symbian have shaken off the grip of its owners? At least one former executive thinks so.

"Very early on we wanted to avoid becoming an industry co-operative - like the Milk Marketing Board. We wanted to avoid becoming a bag of bits. But that's what happened," says Juha Christensen today. If Symbian had been able to IPO, it could have escaped the clutches of its owners - and even challenged Nokia to like it or lump. "Where would it have found another operating system from?" he wonders.

Others think that's fanciful. "Would Nokia ever have helped no name manufacturers bring out a leading edge smartphone?" asks one former executive rhetorically.

"Symbian's management team really didn't understand the tigers it had by their tails," says one leading engineer. "They were woefully inadequate to manage the politics of the companies whose futures they were trying to mold."

But where Symbian pioneered the smartphone field, others seem to have learned valuable lessons.

"Symbian failed because it did licensing first. But if you bring a product to market, then license it to others, those licensees will come,” says Matt Millar. “All they needed to do was work with Nokia, it was world's number one. If you were an OS licensee you'd have given your back teeth to work with Nokia. You just needed to sit down, focus, and create some amazing products with them and then take those and license them to other people.”

Google has learned the lesson with Android, he says.

“Symbian were too socialist, and not capitalist enough."

Nolan says: "It was a huge opportunity, but we never did deliver on the promise. We never could. We did a deal with the devil."

In the past 10 years, only Google has been able to license a smartphone operating system, and it did so in the wake of the iPhone. Android may yet experience the commoditization and fragmentation Symbian wanted to avoid.

Symbian was to remain an important industry force for a decade, but would never fulfill the ambition of being a new kind of company – an industry owned council designing the future.

You can’t blame Symbian for that, East says today – as much as industry inertia.

"That’s as much down to the operators as anyone else. They prevented Nokia from doing an end-to-end solution – that’s what Apple has been able to do. They wanted to do that themselves.”®