Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2010/11/17/languages_of_the_geeks/

Speak geek: The world of made-up language

Pointy ears, bumpy foreheads and obscure tongues

Posted in Legal, 17th November 2010 11:43 GMT

The world of invented language is a difficult place to succeed and those who have the patience to create their own tend to have a hard time gathering followers.

Klingon and Elvish are notable exceptions, thanks to the huge fan bases for Star Trek and Lord of The Rings.

Society tends to regard people who learn these languages as über geeky and socially-inept but we often overlook the reasons why they’re so obsessed with the fantasies they love.

Until recently, expanding the speaker numbers was a challenge: conventions were the only place for enthusiasts to gather and sporadic publications the only other method of sharing their passion.

With the internet, mobile app markets and other techie possibilities, these languages now have easily accessible platforms to grow. While such languages thrive, constructed languages, or “conlangs”, that were created in our past generally struggled.

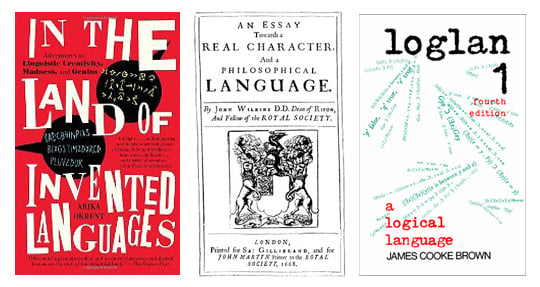

In her book The land of Invented Languages (highly recommended), Akira Okrent tracks down the conlangs that have, in most cases, faded into oblivion. With some pretty wacky ones out there from John Wilkins’ Analytical Language to James Cook Brown’s Loglan, it’s clear why few take off in the first place, even though most were created with respectable goals in mind.

These hard-working, eccentric individuals sought to create a lexicon of words or symbols that remove technical faults in our own languages to create a practical and universal alternative. Okrent supplies wonderful insight into their efforts.

She also delves into successful conlangs that survive today. Those that aren’t supported by pop culture include the widely known Esperanto and my personal favourite; Blissymbolics.

Created by Charles K. Bliss in 1945, Blissymbolics was an attempt at a cross-language unification tool. It has since been adopted by BCI, an institute that teaches language to children with non-speaking disorders such as cerebral palsy.

The language of unity

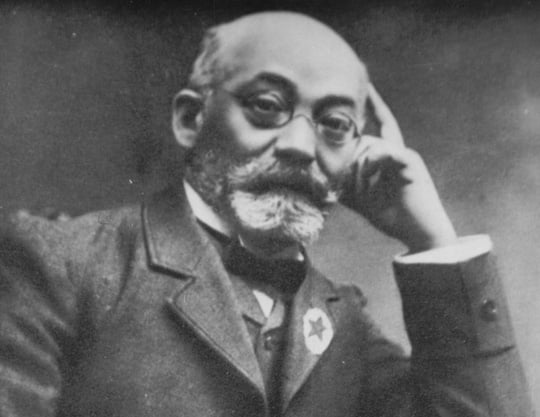

While Bliss was busy creating his symbols, Esperanto was already establishing itself as a globally recognised conlang. Although exact figures are much cause for debate, late psychology professor and longtime Esperantist Sidney Culbert conducted research that suggests by 1988, the number of speakers worldwide ranged from one to two million.

L. L. Zamenmhof

Created toward the end of the 19th century by the philologist L. L. Zamenhof, the concept was, unsurprisingly for the time, an attempt to foster peace and unify the way we communicate. Through much hard work, the language gathered support and after years of specialist periodicals and correspondence, Esperantists held their first world congress in 1905.

Esperantists faced persecution through WWII after the language was falsely perceived to be a secret Jewish plot - A belief of Hitler, publicised in his book Mein Kampf. Despite this, the language survived and was officially recognised by UNESCO in 1954. Its popularity continues to grow today and in 2009, the senate of Brazil passed a bill to make Esperanto an optional part of the curriculum in public schools. That bill would still need to be passed by the Chamber of Deputies, but for a language that few people natively speak worldwide, let alone Brazil, the recognition is monumental.

Esperanto was George Soros's first language

Often described as a good foundation to understand other languages, Esperanto is touted as easy to learn and blossoming with practicality.

These “practical” languages are spoken fluently by few, but are globally accepted and generally respected, so why are those connected with fictional works attributed to the over-zealous or plain nuts and how have they survived the cut?

People once thought that language was a barrier and possibly a cause of regular war and disagreement. The obsession of creating a universal language for peace was lost in translation – literally.

As Okrent puts it, the golden era of conglangers has come to an end.

What next?

Fantasy Islands

Languages created nowadays are typically made for occasional use in a Film, TV series or book collection. Practicality is often ignored. Created to fit the fantasy in mind and not potential linguists, the languages can be deliberately difficult, with awkward pronunciation and limited vocabulary.

The latest communication fad among movie fans is Na’vi - the language spoken in James Cameron’s Avatar. This shows conlanging is on the rise again and with the support of modern tech, it now has a platform to survive.

Klingon also fits this bill: this conlang has seen considerable success and was even used recently in Australian cave tours as well as a full-blown Klingon opera.

Klingon Opera

Photo by Guus Rijven

Linguist Dr Marc Okrand was commissioned by the Star Trek writers to take a handful of phrases coined by James Doohan (Scotty in the original series) and turn them into a fully-fledged language for Klingon use in future Trek films and episodes. Although purpose of creation is thus clear, reasons for attempting to learn the language are not. Aren’t subtitles enough?

Perhaps there’s a possible element of superiority involved - to express complete devotion for a work of fiction, one has to push the boat out further than the rest. To follow suit becomes a must for serious fans who otherwise risk appearing less enthusiastic than others. With so much time already invested, there’s too much pride at stake to appear second best.

The Klingon Alphabet

I struggled to find a Klingon speaker who was prepared to talk to me, so perhaps that pride has its confine. Okrent writes how Klingons can be reserved - a result of the mockery they have to deal with on a regular basis. It appears that imitating an alien race known for its brash demeanour opens the doors for humans to act undignified in return - who'd have thought? Ms. Okrent provides the perfect example of this when checking into a hotel alongside a fully equipped Klingon:

They looked at us, immediately noticing, of course, a costumed member of our group. One of these so-called normal people walked right up to him and, without asking for permission, took out his cell phone to take a picture, saying to no one in particular, and certainly not to the Klingon in question, ‘If I don’t get a picture of this, no one will believe me.’ The Klingon stood tall and posed like a true warrior. At that moment, I knew whose side I was on. The world of Klingon may be based on fiction, but living in it takes real guts.

Put 'em in an institute

The Klingon Language Institute (KLI) has brought enthusiasts together since 1992, mainly through a series of quarterly journals called HolQeD (Klingon for linguistics). The KLI hosts an annual five-day conference called qep’a', which is open to members and anyone vaguely interested. With more than 2500 members from over 50 countries, including Antarctica, qep’a' has a low turn-out, but remains a great place for bumpy-headed Lieutenant Worf lookalikes to socialise.

Scaramouche! Scaramouche!

Operating with Paramount’s permission to use the Star Trek trademarks, the KLI has even translated The Bible and Shakespeare plays into Klingon. This is a tricky job, as only one person is “allowed” to create new words.

Okrand, who admits to having a limited grasp on the language himself, often makes appearances at qep’a' to announce these new words and take suggestions for other translations.

Although phrases such as 'thank you' contradict a Klingon’s temperament and aren't obligatory, the language appears to have evolved for every-day speech and is at a level where it can be used conversationally.

The fact you can select Klingon as the language of choice in Google highlights this. Perhaps it won't be long before we see children brought up with Klingon as their mother-tongue. It has already been attempted.

Homeless Klingon

Photo of Kevin Parker (Amar) by Brian Richardson, Dragoncontv

Linguist Dr d’Armond Speers spoke Klingon to his son for the first three years of his life, while the boy's mother spoke to him in English.

The child displayed moments of understanding Klingon but was apparently uninterested. Speers, struggling to find equivalent words for bottle and diaper, decided enough was enough. His son, now 16, does not speak Klingon, but probably had a grunt at his dad for the embarrassing article.

Elvish is not dead

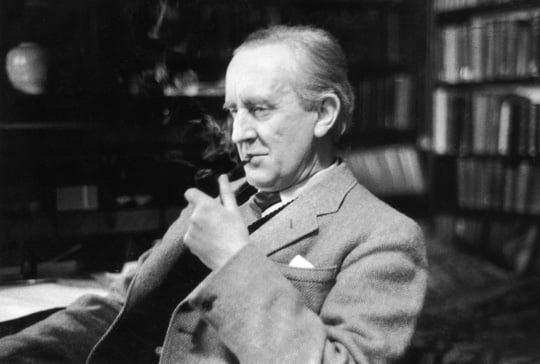

Author and philologist J.R.R. Tolkien constructed several Elvish languages, which in turn inspired the stories we find them in.

J. R. R. Tolkien

Tolkien was no regular myth writer. He believed Mythology touched us all at a very deep level and those that disagree simply don't understand the power it holds. Once, after attempts to get such feelings across to a fellow writer and friend CS Lewis, Tolkien came home, frustrated and wrote this poem. It offers good insight into the conlang mindset.

It’s easy to think that these languages were created for his stories, but Tolkien was primarily a linguist and had dabbled with language invention since his childhood. Through the words he penned, Tolkien’s mind was filled with imaginary worlds, from where the stories originated.

Sindarin and Quenya are Tolkien's two most recognised languages. Sindarin, loosely based on the sounds of Welsh, is spoken by most Elves in the time of LOTR. Quenya, loosely based on the sounds of Finnish, is known as “High-Elven”.

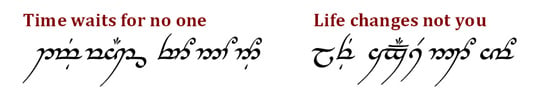

English translated into the Tengwar script

The level of depth that Tolkien went into is amazing and you could be on the Internet for months studying the finer details. Tolkien crafted an entire history and evolution around the tongues of Middle-Earth and even created a fictional philological society that studies them.

Nowadays real people study the languages. There are more than 40 Tolkien societies that arrange numerous events worldwide. These include costumes, dance, drama, good food and re-enactments of battles from the books. However, although poetry readings are common, few include linguistics. Sarehole Mill, a museum in Birmingham, hosts an annual Middle-earth weekend where tongue in cheek Sindarin conversational lessons are offered. Nobody takes it far enough to be practically implemented though.

Modern technologies are increasingly used to bring together followers and recruit. The rise of the mobile app markets is helping.

This summer saw the launch of I write Elvish 1.0.1, an app from Sviluppo iPhone Italia, where users can learn to write their name in Elvish, structure full paragraphs and connect to Facebook to post Elvin encrypted messages to other Ring-bois. Available from the App Store for 64p, the app allows users to overlay script onto supplied backgrounds, or connect to Facebook and adapt existing photos, with the latter marketed as a perfect tool to see how an Elvish tattoo would look.

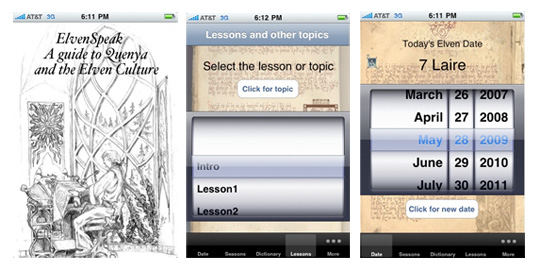

Also, there’s ElvenSpeak, a free app from developers Lassiquendi. Released last year, it offers a 20-course lesson in learning to speak Elvish, which includes a conversational lesson in Quenya. The app features a searchable dictionary, Elvish calendars and traditions, Elven-inspired music and Elven-astronomy lessons.

According to some of the devoted Elves out there, these apps dumb it down for those more interested in getting wedding rings engraved than anything else. Nonetheless, the apps represent an interest in the culture and offer a new platform for expansion.

To speak an Elvish language fluently though is near impossible - the language doesn't work in the modern era. As with Klingon, where the lexicon is specifically written for intergalactic war-talk, Sindarin was created for Middle-earth, a fantasy world where modern culture has no place.

You won’t find phrases like “I’m so cool, I have an iPhone” - though in principle the phrase could be created through "reverse engineering" and close examination. The English word “television” for example, comes from the Greek and Latin words meaning ‘far’ and ‘to see’. The same method can be applied to many forms of language.

The word "television" also exists in Sindarin - “palantír”. A LOTR fan may recognise this as the word Saruman used for “seeing-stones”, the two way television set, or Middle-earth’s version of FaceTime.

Who owns what

Although there are actually those who unofficially construct Elvish words for modern times, this defeats the point, according to "Lúthien", a 39 year-old woman from the Netherlands and speaker of Sindarin. Lúthien is immersed in Tolkien culture and uses Sindarin to write poetry, translate songs and create Middle-earth related artwork. She has almost finished her own Sindarin dictionary too.

Lúthien's art: Nost-na-Lothian in Gondolin

Elvish languages are not made for the modern era - to adapt them to our culture goes against everything they’re used for and dilutes their charm, she says. Lúthien is happy for others to speak Sindarin and insists that being part of a minority is not the appeal, but she says the language should only be used “in the spirit of the Elves”.

Christopher Tolkien owns all copyrights to his father's works and the Tolkien Estate has an official editorial team that sifts through Tolkien’s paperwork and releases new sets of words from time to time.

Lúthien say she must tread carefully though when it comes to the words they publish and worries about legal issues should she include them in her dictionary because the Tolkien estate are very strict about their use.

The Tolkien estate has taken people to court in the past, most notably author Michael Perry for his book Untangling Tolkien: A Chronology and Commentary for The Lord of the Rings. Wired magazine reported back in 2001 how "Elfconners", the name given to those involved with Tolkien's unpublished writings, had acted as "informal copyright police" and attempted to prevent publications by other linguistic scholars.

Copyright disputes in Middle-earth: who knew? ®

On learning Elvish

Ever since her father read The Hobbit at bedtimes, Lúthien dreamed of learning the languages. Aged thirteen, she pored through The LOTR appendixes to learn more. She tried to master the Tengwar script but couldn’t sustain it and while her passion remained undimmed, she struggled to find enough resources to continue. Three years ago, browsing the internet, Lúthien discovered other Tolkien fans and additional material that assured her it could be done. In 2008, she started to take it seriously.

Can't see the video? Download Flash Player from Adobe.com

Lúthien has attended just one Elvish gathering and with with face-to-face congregation a rarity, she often uses Skype to talk with enthusiasts. Subscription to Elfling, the Yahoo mailing list, along with several forums, including Parendili, appear to be the best places to meet - more signs that modern tech helps to further the widespread celebration of Tolkien’s languages.

Lúthien feels Sindarin takes her to a fantasy realm, much to the same degree it originally took Tolkien, before he turned the languages into the core of LOTR.