Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2010/11/15/google_accused_of_hard_coding_own_results_into_search/

Google accused of hard-coding own links in search

Harvard prof waves Google antitrust 'smoking gun'

Posted in Legal, 15th November 2010 17:56 GMT

Updated Update: This story has been updated with comment from Google.

In a still-simmering Google antitrust complaint, UK-based vertical search outfit Foundem accuses the Mountain View web giant of using its search monopoly to unfairly favor its own services over those of its competitors. Google chief executive Eric Schmidt denies the accusation, arguing that the company's search engine always delivers "the best end-user outcome." But Harvard professor and noted Google watcher Ben Edelman believes otherwise.

He says he's found a "smoking gun" that indicates Google's search engine does in fact favor the company's own services.

Edelman says his evidence shows that Google may "hard-code" its own links to appear at the top of certain algorithmic search result pages, including links for Google Finance, Google Health, and other Mountain View-operated web services. In other words, these links appear independently of Google's search algorithms, undermining the company's off-stated claims that its search results are unbiased and completely automated.

"Google's use of hard-coding and other search bias gives Google an important advantage in any sector that requires or benefits from substantial algorithmic search traffic," Edelman writes in a blog post unveiled on Monday morning. "By directing users to Google services, Google can make its offerings take off in a broad class of services — be it health, finance, maps, video, travel, or otherwise.

"Meanwhile, entrepreneurs recognize and anticipate that Google may bury their results as it favors its own services — blunting the incentive to build a business that competes with Google or competes with a service Google might plausibly develop. With Google already putting its Health and Finance sites first, even when user consensus is that other sites are preferable in these categories, it's easy to envision a future where user preferences and genuine excellence are less important than Google's rote power."

The implications are potentially far-reaching. "This could be very important in the long run," Edelman tells The Register. "In the long run, when Google is sued in comprehensive antitrust litigation and we get to see the processes that yield the [search results], this will be one of the smoking guns that guides the discovery."

Asked to comment, a Google spokesman provided the following statement: "We built Google for users, not websites, and while think it’s important to be transparent with websites about how we rank sites, ultimately our goal is to give users the most useful answer possible. Sometimes the most useful answer is a list of links, but other times it's a stock quote, a list of movie times, or quick answer to a question. That's what users want."

He also said that Ben Edelman has been a paid consultant for Microsoft.

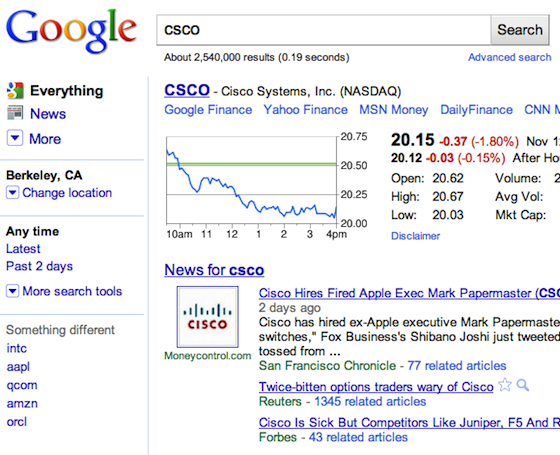

Edelman begins his argument with a standard Google search for "CSCO" — Cisco's stock ticker symbol. Google returns a Google Finance page as the top result — though it's not labeled as such — and the next two most prominent links (a stock price chart and a link that does say "Google Finance") point to the same Google Finance page. This despite the fact that according to comScore, Google Finance is not the web's most popular finance site. You can see the search here (Google's "Instant" search is turned off, but the same behavior can be reproduced when it's turned on):

The question, Edelman says, is whether or not Google algorithms select Google Finance for these top spots. "How do Google's less popular services come to receive such valuable placements? Does favorable pagerank (or other favorable reputation) of google.com spill over onto other Google services to guarantee top position under standard ranking algorithms? Or have Google staff manually adjusted ('hard-coded') search results to give favored treatment to other Google services?" he asks.

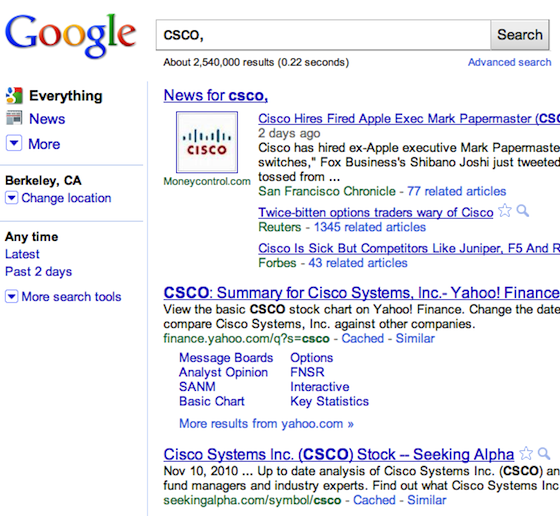

Yes, Edelman argues they're hard-coded. To buttress this claim, he performs the same "CSCO" search, but with a comma at the end. With the typical algorithmic search, adding a comma doesn't affect the results (Edelman offers a "comma search tool" to show this). But if you search on "CSCO," — rather than "CSCO" — those Google Finance links vanish:

"What system design could explain that disappearance?" Edelman says. "My best assessment: If Google staff manually specified that a given result should appear at the top of results when users search for a specific search term, they might well forget to include search term variants with appended commas. Then a user searching for an unexpected variant, including by adding a comma, can see 'true' Google algorithmic search, unaffected by the manual overrides."

Edelman points out similar behavior with searches involving health terms. If you search on "acne", the three most prominent results are for Google Health. But these disappear if you add a comma — or make other small changes. And the same goes for every term listed in Google's Health Topics index. "While exact searches for the listed terms yield prominent links to Google Health, any tiny variant causes the Google Health results to disappear completely," he says.

He also lays out several other similar examples, spanning everything from travel deals to movie listings to patent filings.

Google comes clean

As Edelman points out, his findings run contrary to Google's age-old description of its search engine. "No manual intervention," Google Fellow Amit Singhal said in a 2008 blog post. "The final ordering of the results is decided by our algorithms…not manually by us. We believe that the subjective judgment of any individual is…subjective, and information distilled by our algorithms…is better than individual subjectivity."

But Edelman also digs up an unguarded moment where the company seems to admit to the sort of hard-coding he describes. It may be his most significant find. "When we roll[ed] out Google Finance, we did put the Google link first. It seems only fair, right?" vice president of search Marissa Mayer said during a June 2007 public appearance. "We do all the work for the search page and all these other things, so we do put it first...That has actually been our policy, since then, because of Finance. So for Google Maps again, it's the first link." You can see her on video here:

'

This is just the sort of behavior Foundem criticizes in its EU antitrust complaint. The complaint is under seal, but it's mirrored by a stateside FCC filing. Foundem homes in on what Google calls Universal Search, a search setup — introduced in May 2007 — where Google, well, inserts links from other Google services into prominent positions on its search results pages. There are certain Universal Search results that point to content from third-party companies — "news" links, for example, point to third-party news stories — but in many other cases they point to Google pages, including pages for Google Maps and Google Product Search.

Foundem contends that with Universal Search, Google is unfairly positioning its services over competing services. "Google should not discriminate — at all — not even in favor of Google's own services," Foundem co-founder Shivaun Raff has told The Reg, accusing Google of using completely different algorithms to rank results for its own services. Google says that Universal Search is a way of "blending" its services with web results, but as Foundem points out in its FCC filing, others have called it "bundling."

The comparison is obvious. Foundem is arguing that in much the same way Microsoft unfairly bundled applications with Windows, Google is unfairly bundling its own services on its search engine, which controls an estimated 85 per cent of the market — if not more. Foundem produces stats showing that since the arrival of Universal Search, Google's market share in areas such as online maps and product search has increased significantly. In short, Foundem says, Mountain View has exerted discriminatory market power to demote such competitors such as MapQuest and Pricegrabber.

Google may or may not classify its allegedly hard-coded Google Finance and Google Health results as examples of Universal Search in action. But Edelman sees them as a slightly different thing. When Google slips in, say, Google Maps links via Universal Search, it labels them as "maps" results. You don't get the same sort of label with Edelman's searches. "With the CSCO search, Google does say 'these are the finance results," he says. "They're masquerading as algorithmic results. They look like algorithmic results. They don't look like something else."

What's more, Universal Search appears to use separate algorithms from those used for other results on the page. With his examples, Edelman believes that Google is not merely shifting to other algorithms. He believes the company has indeed hard-coded specific results. "If you look at Google's Health Topics index page, every one of those terms is hard-coded," he says.

Ben Edelman

But he does see the similarity to Foundem's argument. And he sees the Microsoft "bundling" analogy. But he believes that Google's hard-coding goes beyond Redmond's setup. "There are some similarities, and some differences," he tells us. "With Windows, at least you could install another web browser. What does it mean to install another map program into Google? You can't.

"You could go maps.yahoo.com, if that's what you want. But you could never have a different one that was integrated nicely into the web browser. Whereas in the operating system context, if you installed Netscape and you double-clicked on a .html file, it would open in Netscape...It would be fully integrated in the relevant sense. But it's hard to see how Yahoo! Maps could get to be fully integrated with Google in the relevant sense. I don't think there's been any discussion of that." ®