Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2010/11/03/the_science_of_battlestar_galactica/

Shut up, Spock! How Battlestar Galactica beat Trek babble

TV science adviser talks Cylons with El Reg

Posted in Science, 3rd November 2010 06:54 GMT

Interview No guns firing beams of light. No photon torpedoes. And, sorry, no aliens – menacing or otherwise. The "re-imagined" Battlestar Galactica that concluded last year couldn't have been further from its 1970s namesake – or from what most of us think of as sci-fi.

In fact, the science and technology in the award-winning show – the story of survivors of a human civilization fleeing a nuclear holocaust unleashed by machines and now searching for a new home called Earth – couldn't have been more hidden or more familiar in some cases.

What we got was guns firing lead bullets, battleships hurling nuclear missiles at each other, and a space vessel - Galactica - that was more mauled aircraft carrier than sleek ship.

The reason? BSG creator and executive producer Ronald D. Moore ruled that there would be no technobabble - no sciency-sounding words or theories that sci-fi geeks typically feed on.

Moore has written for Star Trek Voyager, and he believed that story development in the series had been hindered by the sort of Roddenberrian nonsense that was used to explain how the original USS Enterprise worked. The result: BSG was barely science fiction - at least to purists.

At the same time, Moore hired a science adviser - Kevin Grazier - who works on NASA Jet Propulsion Labs' Cassini mission to explore Saturn's system, has six university degrees in science and computing to his name, and packs a background in naval aeronautics under his belt. Moore wasn't messing around when it came to getting the "facts" right.

Kevin Grazier, Galactica's science adviser

Grazier's job was to help keep the technology and science real and credible - even when there were some massive leaps. Grazier didn't just make sure that there was a reason for what we saw - bullets instead of lasers - but also that when the science bit did break into the open, it was more mind-blowing than the writers could have conceived - such as when the humans discover their mechanical Cylon persecutors have evolved to look human.

Grazier – whose new book The Science of Battlestar Galactica finally puts geeks out of their misery by explaining the "hows", "whys", and "what ifs" – is blunt in explaining BSG's success. BSG, he says, was not a technology show.

This formula worked. BSG became a cult and critical hit. BSG was the first ever sci-fi show to earn a prestigious Peabody Award for its treatment of contemporary subjects. It won over fans of the 1970s original who were initially suspicious of Moore's plans for their beloved show, and BSG secured a rarity for any TV sci-fi creation: the nodding approval of members of the science community.

The Syfy channel now hopes to re-capture BSG's magic, having just commissioned Battlestar Galactica: Blood & Chrome, set in the 10th year of the Cylon Wars that predate BSG.

Talking to us about his book (written with colleague Patrick Di Justo), Grazier makes it clear that it's the details on science and technology peppered through the BSG script that helped sell the drama and defined Galactica's world. It was a world that – in terms of technology – wasn't too distant from ours.

In their book, Grazier and Di Justo span physics, computer science, navigation systems, metals, propulsion systems, weapons and warfare, and biology, as they explain what's going on behind the scenes in BSG.

Take lasers, a staple of any sci-fi. Grazier's book explains the physical limitations of firing the equivalent of an M-16 round in laser terms. He also dispatches the idea depicted in some sci-fi that being pulled into the vacuum of space will suck your eyeballs from their sockets or cause your organs to explode (thanks, Total Recall and Outland). Rather, you'll get a wicked case of the bends, which occurs when nitrogen bubbles enter the bloodstream. It can prove lethal to ocean divers who surface too quickly.

Grazier probes the technical networking and data-transfer capacities and requirements it might take for an entire Cylon to download for "resurrection." Grazier, the NASA man whose day job involves data transfers across some 743 million miles between Earth and Saturn from the Cassini craft, calculates this might involve terabytes per Cylon and take days to transfer - depending on your Wi-Fi connection, of course.

In space, not everything works

Their book also explains not just how things can and do work in space, but also how they might not: such as in one episode when Galactica plummets through a planet's atmosphere to launch a surprise attack. The resulting shock wave and the plasma enveloping Galactica's vaporizing hull would likely prevent the launch of her Viper fighters.

We're spared these kinds of details in the show, and the book's been written to answer those who keep hitting Grazier up for answers. BSG was primarily the story of humans driven to desperate and questionable lengths as machines evolve.

In the era of Iraq and George W. Bush, Abu Ghraib and WMD, in an age of paranoia and sneak terrorist attacks, BSG wasn't a story about spacemen. It saw supposedly civilized humans torture their Cylon prisoners, the military shoot and kill un-armed civilians to force them back to work, and vigilantes on Galactica blow human Cylon collaborators to a cold and airless death through an airlock. All the while, people got married. They had kids. They had affairs with other crew members. BSG was an epic of morality, motive, and humanity painted on the black canvas of space. But it didn't preach.

Running rings around sci-fi

According to Grazier, the idea was mostly to weave the science and technology into the fabric of daily life, let the drama unfold and characters speak and interact without breaking the dramatic spell. To make the technology as natural to the characters as an iPhone or a laptop is to the viewer in their daily life today.

"We were just describing these peoples' days and the things you see are just part of their days," he said.

"The goal of the screen writer is never to wake the audience from your dream," he said. "When you do, the person goes from being immersed in that world to being: 'Hang on, I'm a person sitting in a chair in the 21st century watching TV.' You've given them 'the bump' [Inception reference, for any Inception virgins still out there]. We tried not to do that."

Grazier worked closely with Galactica's writers, advising on their ideas and the producers' concepts about where they wanted to take the show.

Science was respected, he said, but in any clash between drama and science, the drama won. The science was also eschewed when Galactica touched on something spiritual, such as the Cylons' exploration of God. That said, Grazier is complimentary about his colleagues. "They had a science adviser, but they didn't need to listen to him. Even when they didn't take my suggestions I never felt that I wasn't listened to, and that's special - that's rare."

Why was Grazier listened to in the first place?

Grazier is a scientist on the Cassini mission to explore the Saturn system. He works on the tiny craft's Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) - a visual-light camera that's been sending images of the planet, rings and moons back to Earth - and he's a planning engineer who writes and runs the software that tells the other scientists when they can take their observations based on time, distance from target, and so on. He has degrees in computer science, physics, geology, geo-physics and applied planetary physics from Purdue University, Oakland University, and the University of California at Los Angeles. (UCLA).

Boffinry aside, he has military creds: he was targeting a career as a US Navy pilot, and he was a member of the Navy's Recruit Training Command (RTC) until a knee injury grounded him. What Grazier didn't know, he soaked up through events like a day-long look around the carrier USS Constellation, now decommissioned, in preparation for BSG.

The USS Constellation: a role model for today's Galactica

This explains Galactica's decidedly military feel - a world away from the camp 1970s romp. Pilots of the Viper fighters launching from Galactica went through a pre-launch checklist rather than simply jumping in their cockpits and hitting "go" as per Glen A. Larson's original. Galactica has marines onboard, not just the buccaneering pilots of the 70s series. And Galactica's bridge crew drops terms like CBDR to describe incoming Cylon attack vessels - CBDR means Constant Bearing Decreasing Range, naval shorthand to describe a collision course. "Next day [after one particular episode] I'm on the phone talking to may dad in Pennsylvania, and he says: 'So, CBDR - that you?' And I say: 'Yes'. He's an old navy guy," Grazier admits with a sly smile on his face.

Such references were vital to keeping BSG's technology touchable and keeping viewers absorbed. "We wanted reality," Grazier says. "The average audience member wants to think he's watching life aboard an aircraft carrier - until you see the Cylons."

Why was Galactica so militarized? "It had to be," Grazier replies. "You're on an aircraft carrier in space. I think the way the military people were portrayed was brilliant - because they weren't propagandist heroes. They weren't baby-killing mercenaries. They had a job to do."

Any decent sci-fi involves some form of faster-than-light travel and Galactica was no exception to this convention - it just stood out with its execution. Grazier's fingerprints are all over Galactica's propulsion system: Faster-Than-Light (FTL).

We're gonna need more power

Nasa's man faced some constraints in coming up with the system, which is explored in his book. Galactica had to use a vernacular that was familiar to the audience, and there had to be a visual aspect. But from there, BSG departed from tradition. Play your BSG DVDs, and you'll notice how you're never actually onboard Galactica during a jump, as opposed to being on the deck of the Enterprise during warp speed flight or crammed in next to a Wookie while traveling through hyperspace in the Millennium Falcon. All you see is Galactica disappear and reappear with a startling burst.

It was Moore who laid down the concept of a warp-drive-like folding of space, with the ship simply punching a hole through from one side to the next. It was Grazier who filled in the details, supplied at short notice after one coffee-filled night pacing a hotel room.

Grazier envisioned a mechanical component and large capacitors. He tried to explain the concept of spinning up the FTL drive - "spin up the FTL" is a phrase used by crew that's a series of calculations and steps taken in the countdown to jumping - and the special effects of the light involved. The component-and-capacitors part is important, because they're what Chief Tyrol proceeds to rip out to prevent one particular episode's FTL jump.

In his book, Grazier explains how FTL's folding of space might work versus Star Trek's warping or Star Wars' hyperspace. He also explores what might drive Galactica's sub-light engine, discounting liquid fuels, Ion and nuclear, and determining Galactica would need something twice as powerful as the most powerful rocket fuel on Earth: Ammonium Perchlorate Composite Propellant used in the Space Shuttle's solid-rocket boosters.

Finding a fictional Earth

NASA's man admits this is science fiction not science fact and that he doesn't really have an answer for this kind of travel, but it worked in the context of BSG. "If I really knew how it worked, I'd be in Stockholm," he said, meaning he'd have received a Nobel Prize. "But it's more of an explanation that you get in most sci-fi shows."

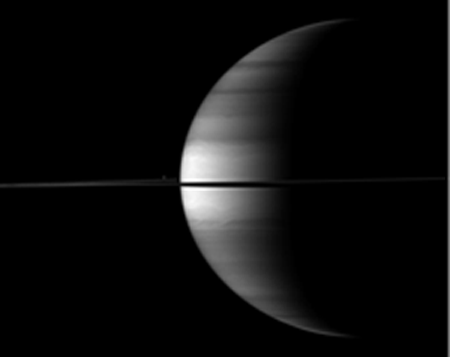

Grazier's work on NASA's Cassini also comes through in the show and this book. Cassini started as a four-year mission to explore the Saturn system, including the gas giant's moon Titan. The Cassini craft launched in 1997 and the hardy little machine's job has now been extended a third time, to 2017.

Cassini has been capturing and sending back images of Saturn, its rings and moons, which you can see here. As investigation scientist on the ISS visual-light camera that captures those images, it's part of Grazier's job to help capture those images by making sure Cassini's in the right place at the right time. Otherwise, you get a black screen.

When Galactica's producers got serious about finding Earth, Grazier was called in to give a talk to the writers on astronomical signs, portents and landmarks that could be used to find or reference the way to Earth. His work came to paint the backdrop for an important part of the show - the humans' zeroing in on Earth's part of the galaxy.

"We looked at clusters, pulsars, different colors of stars, supernovae - and they were all incorporated into the search for Earth, as breadcrumbs along the way on the path to Earth," he said.

Saturn as seen by NASA's Cassini: a breadcrumb home for Galactica

In one storyline spanning two episodes, ace-but-troubled Viper pilot Starbuck is lost on what the writers described as a "Titan-like moon orbiting a Saturn-like planet." "That wasn't my idea," Grazier was quick to point out. "But I was able to provide some input into those two episodes, so there was some indirect Cassini influence."

Starbuck proceeds to be troubled by visions of a gas planet surrounded by rings, with a trinary star system and a comet. That gas planet is clearly Saturn. Polaris – our North Star and a navigation aid to sailors for centuries – happens to be a trinary star system composed of three stars. Starbuck's visions are controversial, even sparking mutiny, but they do lead to the humans' discovery of Earth. "The rings around the planet were supposed to be a big deal... that's based on Cassini. Unless you look very carefully you will never see it," he said.

Grazier's influence wasn't always so subtle. In one cliffhanger storyline, Galactica was separated from its rag-tag fleet of civilian ships and fellow survivors. "The writers said: 'Here's what we want to do: separate Galactica from the fleet. How do we get into it, and how the hell do we get out of it, and we have to incorporate in that jumping back and we also have to incorporate fighting off Cylons while we do it'," Grazier said.

Grazier's inspiration: Cassini.

"When we image a small moon - something that's not in a well defined position - we will always update the best-known coordinates of the last position of the spacecraft so you can target it and you are not getting a blank image," Grazier said.

He needs Cassini to be pointing in the right direction at the right time to grab a particular image. The distance between Cassini and Earth is some 743 million miles at its closest point, so anything less than absolutely precise coordinates means you miss getting the image.

"I thought: 'What happens if they do something similar', they are sending up the co-ordinates constantly to update the jump coordinates in case of an emergency and the 'minus first version' didn't get updated, and though: 'That would explain it'."

"This is from special relativity: there is no fixed frame of reference in the universe, so instead you have to move everything backwards, to integrate backwards, which is what they did when they [Galactica] went back to Caprica [the humans' home planet nuked by the Cylons and abandoned in the search for Earth] to figure out the coordinates and jump there to rejoin the fleet."

Here comes 'the science' bit

It's a complicated situation – and one that could easily fall victim to technobabble if one tried to explain what was happening.

Yet, while technobabble wasn't allowed, scientific language and reasons were woven into the dialogue by way of explanation. "A lot of writers feel if you get into too much of the exposition you can get boring, but at the same time the writers we had in Galactica could incorporate it into natural dialogue instead of going," Grazier effects a loud staccato voice: "'OK. I'm going to tell you what's going on now'." Then he returns to his usual voice: "The explanation was worked naturally into the dialogue more often than not."

This attention to scientific detail didn't just help carve out a niche with fans and critics, it also helped BSG score credibility among members of the real scientific community if not web nerds

Fanbois versus PHDs: the science community votes

"A lot of people get frustrated," Grazier said of BSG's following. "You have to have a good sense of when the science can be stretched and not be absolute. I found it's people with a little science education who will give us grief online. People with a lot of science education are more forgiving. They'd say: 'You did this here. If you did this, it might work.' The people with PHDs in physics are more willing to give us leeway. That's counter-intuitive!"

A clear sci-fi fan, Grazier gets frustrated with films that try to artificially ramp up the dramatic content when the science itself would have been dramatic enough. Just "getting it right" can create the impact - something he aimed for in BSG.

Grazier cites 1998's blockbuster Armageddon, when a "planet-killing" asteroid the size of Texas - Texas is the US' second largest state with 261,797 square miles of land FYI - is bearing down on Earth, and roughnecks led by Bruce Willis swing into action. Grazier claims it lost him less than a minute from the start of the film.

"In the first 39 seconds, we see the K-T Impact of the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. Had they had a science adviser, it would have been more dramatic," he reckons.

"Charlton Heston said in his best Moses voice [over]: 'It hit with the force of 10,000 nuclear weapons.' It was more like 41 million. It was only four to six miles across, maybe 10, but that was a lot of energy, and had they checked on the science they could have made it much more dramatic. They didn't and they just picked some number out of a hat."

Smaller than Texas, but just as bad: how the K-T Impact might have looked according to NASA

Details for Grazier clearly lend credibility and sell a story. He's a huge fan of 2010: The Year We Make Contact over the more widely acclaimed 2001: A Space Odyssey, also by Arthur C. Clarke. Why? Details.

"When they approach Discovery [the ship that's home to the murderous Hall 9000] in orbit around Jupiter's moon Io and it's covered in sulphur, which it would be because it's a volcanic moon, I thought: 'How cool is that?' That's a level of detail they didn't have to do but they thought about it."

"That movie is influential for me in terms of how much the science is right. There are a few places where they say: 'Come take a leap with me,' such as adding mass to Jupiter to turn it into a star and the fact the moons didn't vaporize, but that was one that was real influential for me because of the level of detail and how well they got the science right."

It was details that got him hooked on BSG too, when Moore was touting his idea. Grazier was attending Galacticon, celebrating the anniversary of the original Battlestar Galactica series, where Moore showed clips from the then up-coming miniseries.

"The moment I realized I wanted to work on the show was [when] they were lining up a Viper in a launch tube, and you see the wind swirling down and the water condensing as it swirls down the launch tube. That was the moment when I said: 'I so want to work on that.'"

He asked a film industry contact for an interview with Moore and got it. Grazier got five minutes, and Moore asked about Grazier's military background, which turned up the fact Moore was also ex-RTC. A recommendation helped nail it.

How did Grazier end up as a science adviser before that? Studying as a UCLA grad student, he pitched an unsolicited manuscript to Paramount for an episode of Voyager with a writing partner. The studio got 3,000 such manuscripts a year with the vast majority rejected, but Grazier's was read. He was asked to pitch more and one of the people he pitched was Voyager's Michael Taylor, who went on to join the BSG crew.

To infinity and beyond

Since then, Grazier's worked on Syfy's Eureka - set in an Oregon town populated by boffins working for the Global Dynamics corporation - and consulted on Warner Bros.' planned space thriller Gravity, and the pilot of NBC's political and science thriller The Event. When The Reg last spoke to Grazier, he'd been filming a series for National Geographic on - yes - space. It covers stars, things you can mine in space, and the effects of travel in space on the body.

Despite his TV and film commitments, Grazier says he's not a full-time science consultant or adviser. His job remains with NASA and Cassini. But sci-fi does leak into his daily life: Grazier describes his office as "nirvana" with its life-size poster of a Cylon Centurion, a 4x6 poster from Eureka and models of the USS Enterprise and a Klingon Bird of Prey.

He has, he says, a dream job. Two dream jobs, in fact: science and science fiction. For someone who was a kid when man landed on the Moon and the first episodes of Star Trek hit US TV, that's hard to beat. ®

You can find out more about The Science of Battlestar Galactica, including where to buy it, here.