Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2010/09/14/preston_mcafee/

Yahoo! economist rebuilds ad empire with 'Magic Formula'

Why Carol Bartz wears math when it's chilly

Posted in Legal, 14th September 2010 22:43 GMT

Yahoo! CEO Carol Bartz owns a sweatshirt emblazoned with Preston McAfee's math. McAfee is an economist, but he's the sort of economist who's actually useful. In the early-90s, he helped build the simultaneous ascending auction, a mathematical contraption that governments across the globe have since used to license over $100 million in wireless spectrum. And nowadays, as the man who oversees the microeconomics and social sciences research group at Yahoo!, he builds things that are so useful, they wind up on the boss's chest.

"I'm a member of a group of people — you might even call it a movement — who do economics as an engineering discipline," McAfee tells The Reg. "If you look at the humor of economics, it's all about how useless economists are. What economists have traditionally done for the world is block stupid ideas. Economists go to Washington just so they can stop Washington from doing the silly things it would otherwise do. That may serve a greater purpose, but it's still a negative thing to do.

"Economics as engineering discipline is all about building things with economics that are positive — as opposed to stopping things, things that won't work."

McAfee is a disciple of Nobel Prize–winning economist Roger Myerson, whose "mechanism design theory" has been used to build everything from efficient trading systems to reliable voting procedures. "In the same way a physicist develops a theory and an engineer builds something that actually uses that theory, we're the kind of people who use scientific principles to actually make markets or interactions among people work better, work more smoothly," McAfee says.

It's no surprise that he — and so many like-minded souls — wound up at Yahoo!, whose online ad empire is a global market unto itself. The company's Right Media exchange — a display advertising marketplace that matches advertisers with publishers and ad networks — is by one measure the largest exchange in the world, running over nine billion auctions each day. The US-Euro foreign exchange market generates more dollars. And Google AdWords may as well. But there are other things to consider.

"It's not an accident that I and many other [economic engineers] are here," McAfee says. "Yahoo! is more open."

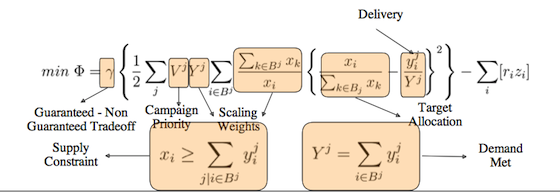

Bartz refers to the McAfee creation on her sweatshirt as The Magic Formula. This epic piece of math — which is also worn by McAfee and his children on occasion — made its debut earlier this year. In short, it's a formula designed to keep Yahoo!'s largest advertisers as happy as possible. It lets each of those guaranteed-contract advertisers pick and choose — in remarkably precise fashion — how their ads are targeted, even though there are more than three trillion possible targets.

The formula

"What this formula does is simplify the problem of how do we figure out what inventory goes to what advertiser, when advertisers have all these conflicting needs and desires," McAfee explains.

Yes, Yahoo! has advertisers who only want to reach women between the ages of twenty and thirty. But it also has advertisers who only want to advertise in cities where the sun is shining. There are brokerage houses who only want to advertise when the stock market is up. And, yes, there are those interested in serving ads according to your online behavior. Among Yahoo!'s two hundred largest advertisers, McAfee says, there are three trillion possible categories. And his formula handles them all.

The magic is that there is no magic

"What is really 'magic' about this is that it gave us a backdoor way to price three trillion different pieces of advertiser demand," McAfee says. The trick is that it doesn't actually price all three trillion categories. The formula reduces the calculation down to a pair of parameters per campaign — that's a total of 400 parameters for those 200 large advertisers — and it prices the ads with real-time bidding, mimicking an ad-exchange model. Yahoo!, in other words, bids on behalf of the advertisers.

"The pricing is the outcome of the bidding, so we don't have to price everything in advance. We can price them after the fact. We can price them in the process of executing the campaign," McAfee explains. "What that does is take a problem that was — in principle — three trillion dimensions and reduces it to 400 dimensions."

The setup also gives Yahoo! fine-grain control over each advertiser's campaign. "It gives us a dial to favor an advertiser," he continues. "If one of our advertisers is not getting enough impressions, we turn the dial and increase their bids, to make sure we fulfill the contract."

Before Yahoo! began rolling out the system this past January, ad placement was at the opposite end of the spectrum. "We would basically flip a coin as to what ad you saw," he says. "It wasn't completely random — we let you, say, target an ad to someone in San Jose, and if a San Jose campaign was behind, we would push it — but it was pretty much random."

Preston McAfee

The new setup — part of Yahoo!’s display ad serving system (known internally as "IMS2") — has now been deployed across North America, and it's designed to eventually integrate with the company's Right Media exchange, where smaller advertisers — those without guaranteed contracts — bid for ad placements across a sweeping network of websites, including Yahoo!'s. Currently, it doesn't fully integrate with Right Media, but it does take pricing input from the exchange. If a guaranteed advertiser wants to advertise to men over the age of 65, for instance, the system will ask how much men over 65 are selling for on the exchange.

But the point of this new system — and this will be the case even when it integrates with Right Media — is to give the contract advertisers what they want before its snapped up by clever bidders on the exchange. "It's a way of protecting our most valuable advertisers," McAfee says. "We don't want to just expose those guys to our ad exchange. If we expose the inventory to the exchange, we allow somebody else to buy the really good stuff, and that's a threat to our best advertisers."

The exchange model is a wonderfully efficient means of distributing ad inventory, but it may work against the big guns. "If some smart guy comes in and says I'm going to buy all of the high-income areas of the country — which is easy enough to do based on a census table look-up — a big advertiser may end up with only the poor neighborhoods. And they're going to be really unhappy."

IMS2 gives the contact advertisers what they want and then exposes the leftovers on the exchange. But at the same time, it delivers exchange-like efficiency.

It's no wonder Bartz wears that math on her chest. ®