Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2010/09/10/adobe_security_analysis/

What Adobe could learn from The Flying Wallendas

Do security safety nets make Reader less safe?

Posted in Security, 10th September 2010 19:25 GMT

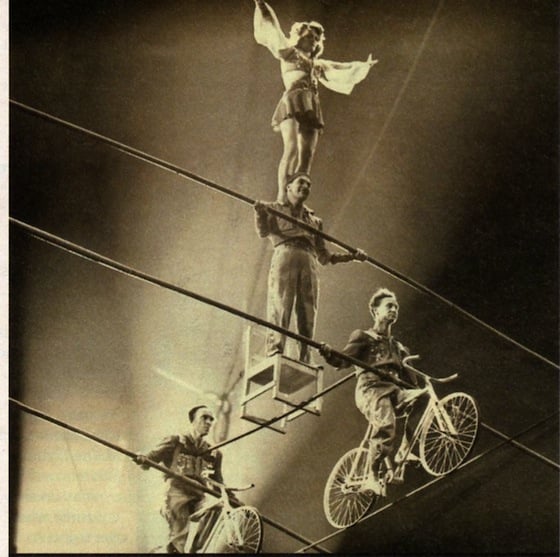

Analysis The Flying Wallendas were a legendary circus troupe that performed death-defying acts from a high wire without the use of nets or safety devices of any kind. Even when they performed their world-famous four-person, three-level pyramid act 50 feet in the air, patriarch Karl Wallenda steadfastly eschewed nets out of a belief they sapped the aerialists' concentration.

“He did feel that a net could cause you to be sloppy and not really train the way you should to prepare for a performance and therefore give you a false security,” Karl Wallenda's grandson, Tino, said recently from a performance in Greenfield, Massachusetts. “It makes the audience feel comfortable more than it makes us, the performers, feel comfortable.”

Perhaps the recently discovered attack targeting a code-execution vulnerability in Adobe's near-ubiquitous Reader application should raise similar concerns in the software arena.

The 15-page PDF was able to compromise PCs even when they ran Reader on versions of Microsoft Windows that are fortified with protections designed to lessen the damage from garden-variety bugs – such as the stack overflow being targeted in Reader. While white-hat hackers have demonstrated similar techniques over the past 18 months or so, the Reader exploit marks one of the first times they've been used in the wild, Nicolas Joly, a vulnerability researcher with Vupen Security, said earlier this week.

Constantly risking absurdity security

Particularly hard to defeat – or so we've been told – is a protection known as ASLR, or address space layout randomization, which Microsoft introduced with Windows Vista. It loads system components in a different memory location each time a machine is rebooted. That means that even when attackers have identified a vulnerability that allows malicious code to be injected into the operating system, they will have a hard time knowing where to find and run it.

The criminals behind the Adobe exploit worked around this feature by piggybacking their attack on a Reader file known as icucnv36.dll, which because of an oversight at Adobe, doesn't make use of ASLR. With a single mistake, a protection Microsoft spent years developing was undone. An Adobe spokeswoman said the company will “perform a thorough review of each vulnerability and our response” – including the lack of ASLR protection for the DLL file – so that changes can be made to the development process.

The attack also got around a second major defense that's known as DEP, or data execution prevention. The feature blocks the execution of code in specific memory regions, a measure that prevents the running of malicious shellcode even if it manages to sneak into a known region of computer memory. To do this, the attackers made use of a technique called ROP. Short for return oriented programming, it copies legitimate pieces of code already in use and reorders them in a way that significantly alters what they do.

ROP turned heads when it was successfully used at this year's Pwn2Own hacker contest. It's now becoming a staple of exploits used in the wild. And so are techniques, such as heap spraying and JIT spraying, that defeat ASLR.

And that should be a wake-up call for the entire industry.

Devs on a wire

“The whole idea of counting on certain sections of memory not being being executable and not being in the same place was pretty cool of Microsoft to add as a possibility,” said Gary McGraw, CTO of software security consultancy Cigital. “But it shows that just because that possibility exists on a platform doesn't mean that it's impossible to exploit. That's the key lesson here.”

As someone who regularly works with software companies, McGraw said he regularly encounters developers who view the mitigations as a license to be more careless than they otherwise would be.

“I know that people have kind of relied on DEP and ASLR to make up for not looking carefully enough for stack-based buffer overflows,” he explained. “They say, 'Well, it's alright because they're not going to be able to exploit it because of DEP or ASLR.' Guess what. That's not always true.”

It definitely wasn't true when going up against the authors of the Reader attack, who spared no effort in making sure their exploit compromised as many users as possible. In addition to ROP and heap-spraying techniques, they also embedded three different font libraries into their booby-trapped document to make sure it worked with versions that date back to October.

And lest would-be victims grew suspicious, the attackers signed their malware using a digital certificate belonging to Missouri-based Vantage Credit Union, a member-owned financial institution that encourages customers to “go bankless” by using their online service. According to this analysis by researchers from anti-virus firm Kaspersky, the malware bears the credit union's valid digital imprimatur, which “means that the cybercriminals must have got their hands on the private certificate.”

Vantage Director of Operations Dean Parkinson said the certificate was revoked shortly after his team learned it had been compromised. As a precaution, the server that administered the certificate has been temporarily shut down. The credit union is investigating how the private key was intercepted by the attackers.

The determination and sophistication of the attack, which is also well-documented by researchers from the Metasploit Project, means that mitigations such as DEP and ASLR are best viewed as hinderances that only make attackers' jobs harder. Think of them as a fireproof safe that's intended only to delay the amount of time before the contents are incinerated. Or a bullet-proof vest that provides no protection against a sharp shooter who hits his target in the head.

No doubt, Adobe should proceed with plans to implement a security sandbox that places a container around the application and sensitive parts of the operating system. A similar design seems to have served Google well by upping the ante against attacks that try to exploit its Chrome browser. And, as we've said before, Apple ought to design ASLR into its own Mac OS X.

But no security mitigation should be viewed as a substitute for cleaning up Reader's large, and considerably buggy, code base (or the code of any other widely used application, for that matter). At more than 41MB, it's more than five times as big as competing PDF reader Foxit, and that means there's five times the attack surface to exploit.

The risk of protections like DEP, ASLR and the upcoming sandbox is that Adobe developers will use them as a substitute for the onerous task of conducting line-by-line code audits. Or better yet, rewriting huge chunks of the application from scratch under a better-defined secure development lifecycle, in which security managers have veto power over their coding peers.

Of course, the Wallendas have had a few falls in their history. One came in 1962 while performing their crowd-wowing pyramid act, when two of the performers died. Another came in 1978, when Karl Wallenda fell to his death “because of several misconnected guy ropes along the wire,” according to the official Wallenda website.

But before that, there was a fall in Germany in the 1930s that claimed the life of Willie Wallenda while he was using a safety net at the insistence of his older brother Karl. The tragedy left a lasting impression on Karl that could also prove instructive to developers at Adobe and elsewhere.

“It emphasized that a net is not a foolproof safety device,” Tino said. “We train to do what we do and be successful at it. We train for success, not for failure.” ®

This article was updated to add comment from Vantage Credit Union. It was also updated to correct the definition of DEP.