Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2010/05/12/intel_xeon_server_forecast/

Intel: best days are ahead for servers

Xeons everywhere, virt no cause for alarm

Posted in Channel, 12th May 2010 21:07 GMT

As it comes off yet another global recession, and with a severe freeze in IT spending starting to thaw, Intel's server-chip lineup is perhaps the best Chipzilla The Continuum has ever put into the field - including its much-delayed and much-maligned quad-core Itanium 9300s.

What a difference seven years makes.

Today, rival Advanced Micro Devices doesn't have all the right ideas as it did back in 2003 with its Opterons. Or rather, Intel now has its own versions of those same right ideas while AMD is having a tougher time getting what it deems is its fair share of the microprocessor and chipset sales in the server racket.

In addition, here in 2010 the Sparc and Sparc64 processors from Oracle and Fujitsu, respectively, seem to be frozen in time. And everyone knows that except for three operating systems controlled by HP - OpenVMS, HP-UX, and NonStop - and a smattering of mainframe operating systems in Europe and Japan, Itanium is not a contender. Red Hat and Microsoft have each pulled the plug on Itanium for future development, as IBM and Sun did for AIX and Solaris a decade ago, before Itanium even came to market.

The way, it seems, is clear for the increasing dominance of Intel's Xeon server chips.

But that's not the only thing that has Kirk Skaugen, general manager of Intel's Data Center Group, stoked. The Data Center Group was created this year not just to chase the server-chip market, but also to get Xeons into storage arrays and networking gear, replacing Power and other processors that have long had dominance there.

Skaugen says that a few years back, Intel was getting about 20 per cent of the design wins from storage vendors opting to use its Xeons; this year that share will hit 70 per cent and next year it will be 80 per cent or so, he said. The same kinds of trends are holding in networking gear, which uses Power, MIPS, and other specialized processors.

"This is growth for us," Skaugen said at a meeting yesterday that Intel hosted for Wall Street analysts. "But you won't see it immediately because it takes time for these companies to transition their products."

Think of it as Xeon money in the bank - just like Intel earns in the two-socket workstation space, which currently accounts for about 15 percent of the Xeon CPU's total addressable market and is expected to be about the same in 2014. Intel basically owns the two-socket workstation market - a market that helped put RISC/Unix on the map twenty years ago in commercial computing but one that IBM, Sun, HP, and others could not hold against the onslaught of Windows (and then Linux) coupled with cheap-but-powerful x64 iron.

Another target that Intel has had its eye on for the past decade, Skaugen explained to Wall Street, is the high-end RISC and mainframe server market, a $16bn market Intel felt confident it could finally take down a peg with the new eight-core Nehalem-EX Xeon 7500 processors announced at the end of March.

The way IDC carved up the server racket in 2009, the Xeon family of processors drove about $22bn in server revenues, with Intel taking in about $4.4bn in chip and chipset sales. Itanium servers accounted for $4bn in revenues, and gave Intel an undisclosed revenue share - probably something on the order of $1bn.

AMD's Opterons drove another $3bn in server sales, leaving $16bn that companies shelled out for mainframes, RISC/Unix, and a smattering of proprietary midrange gear. Skaugen estimates that the RISC and mainframe server space represents a $1bn to $1.5bn processor opportunity for Intel - that is, if it can convert those customers to Xeon 7500 systems, which have some of the mainframe-class reliability features missing from prior Xeons but in Itanium.

I know what you are thinking: "How can $22bn in x64 server sales bring Intel about $4.4bn, but converting $16bn in RISC and mainframe sales to Xeons will only bring $1bn to $1.5bn?"

Well, it's precisely because those machines are not compatible with Xeons and do have some features that Xeons are missing that made customers spend a huge amount of money on them. Once customers are willing to convert, however, they're not going to spend the same kind of money. And they don't. And unless the economy gets a lot worse, that base of Unix and proprietary machines will stand pat, out-gassing a little here and there to be sure, like a piece of dry ice. But it won't simply sublimate all at once to Xeons, even if the Xeon 7500s do have a shiny new machine check architecture.

People don't spend money disrupting systems that work, no matter how much they might save. Ask OpenVMS and AS/400 shops. Ask mainframe shops. They'll tell you. This may not make sense, but that's people for you. Messing with something has a potential opportunity cost, just like leaving it alone has an opportunity profit. The money you don't spend on changing something that works can be used to create something new. Which is what IT shops do all the time, and it's not illogical. It is just frustrating - and, in some ways of looking at it, costly.

The Itanic sails on

If you are thinking that Intel is going to abandon Itanium, you're wrong. It just isn't - no matter how embarrassing the comparisons to Nehalem-EX and then Westmere-EX and then SandyBridge-EX will get.

Skaugen said that Intel doubled Itanium performance with the quad-core Tukwila Itanium 9300s, and that it would double it again with the future Poulson Itaniums. And while he conceded that Intel had cut back on Itanium development, it did so by having the Xeon EX line share chipsets and memory buffers with Itanium. Skaugen said that Itanium customers could "invest with confidence" in Itanium machinery, and added that the Itanium line "was more profitable this year than it was last year."

While all this talk of expansion into new markets may excite Skaugen and his colleagues, the installed base of ancient servers - which Skaugen said numbers some 40 million - have them doubly excited. Although Skaugen wasn't clear whether that 40 million number was of servers or CPUs, but his talk generally referred to CPU units. A 40 million–CPU count would be consistent with the belief that there are about 25 million to 30 million true servers worldwide - not counting "desktops on their side," which Skaugen called DOTS servers, as a joke.

According to IDC estimates cited by Intel during their Westmere-EP Xeon 5600 briefings in March, 76 per cent of the x86 and x64 server installed base is comprised of machines using single-core or dual-core processors. Many of these machines are six, seven, eight, or more years old. The 2009 economic downturn pushed out the upgrading of about 1 million servers, and there are maybe 19 million to 23 million machines that need to be brought up to snuff.

Call it three year's worth of server shipments at current rates.

Now, companies can either buy the same number of servers and have a lot more performance, or they can compress a lot more computing into a smaller space. And it's hard to guess which they'll do when the spending starts. But Intel clearly believes that companies will spend, because the power and cooling issues and the increased performance that comes with getting new servers can provide a payback in a few months when you reckon software licenses and juice into the equation.

This is why the Nehalem-EP Xeon 5500 launch of March 2009 resulted in the fastest ramp of a Xeon server chip in Intel's history - and did it during a severe economic downturn. The Xeon 5500s increased from a tiny fraction of Intel's processor-shipment mix to server partners in the first quarter of 2009, ahead of their launch, rocketing in a straight line up to 90 per cent of the mix by the fourth quarter. Not only that, but customers bought faster models with more cache and clock speed, getting better bang for their buck and driving up Intel's average selling price for Xeons - along, of course, with its revenues and profits.

Another greenfield market where Intel is hoping to plop millions of Xeons is small and midrange businesses. Skaugen says there are 18 million SMBs worldwide who have lots of PCs but no servers. There are plenty of sales here to scarf up - if you can get SMBs to buy servers at all. Fifteen years of cheapo servers hasn't had a dramatic effect. Some people don't want servers, even if they need them.

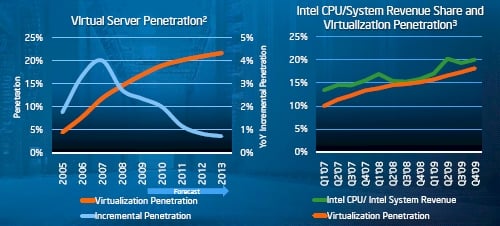

Which leaves the virtualization effect. Skaugen cited statistics from IDC that showed the penetration of virtualization on servers was slowing, and slowing dramatically. Take a gander:

As you can see, the uptake of virtualization hypervisors on new server installations is asymptotically approaching something around 24 per cent in the IDC forecast. Skaugen says that Intel believes the current number to be about 20 per cent of new machines.

The reason it won't get higher is that SMBs won't add virtualization to their entry machines - they'll buy a second server or a disaster-recovery service instead. High-performance computing clusters won't run virtualization, and it doesn't look like workstations will either, for the most part. So there are big swaths of the Xeon's addressable market that will not be virtualized. And that means unit shipments will keep forging ahead, as far as Intel is concerned.

Another reason that Intel is not scared of virtualization is that companies that are virtualizing are buying bigger processors and fatter systems, and Intel has managed to keep its share of system revenue growing more or less in synch with the penetration rate for virtualization. That suggests virtualization is not really hurting Intel. But a footprint count collapse could hurt them, if companies decide to not do a 10X or 20X compression on those vintage x86 and x64 servers with one or two cores per socket.

As far as Intel can calculate, virtualization will only knock off about 1 per cent of the compound annual growth rate projected for servers. Mercury Research stats cited by Skaugen say x64 server CPU units were about 12.5 million last year and will crest at over 20 million by 2013, with a growth rate compounded over those five years of 14 percent. ®