Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2009/06/26/google_youtube_analysis/

Google's real YouTube strategy

Meet the new boss

Posted in Legal, 26th June 2009 14:44 GMT

Telco 2.0 There is an ongoing debate about the size of the losses at YouTube and for how much longer the parent, Google, can afford to fund its errant child’s excessive lifestyle. Credit Suisse put a high price on it; Brough Turner criticised their analysis; RampRate decisively debunked it.

The debate has focused upon YouTube as a standalone service and little attention has been given to the spin-off benefits accruing to the parent. Google controls a significant and growing share of the means of production of the entire internet industry. We argue that ownership of YouTube is a crucial ingredient for Google’s control of the economic rent that Google extracts from the whole of the Internet value chain.

We believe that YouTube is used indirectly to drive profits at the parent, and that Google is currently incentivised to keep these profits hidden from prying eyes. The key indirect benefits accruing to Google of owning YouTube are as follows:

- YouTube gains Google a critical slice of growing online video eyeballs, which will attract more marketing dollars to the Internet as a whole. This is much more important in the USA, where the main competitor Hulu is ad-funded than the UK, where the BBC iPlayer is taxpayer funded;

- YouTube gains Google yet more important meta-data which can be cross-pollinated with data from other Google services;

- YouTube traffic strengthens Google specifically in peering negotiations and generally in network design;

- YouTube is probably a small fraction of Google’s overall cost base, and the spin-off benefits from lower overall unit costs;and

- YouTube positions Google very powerfully for a key role as a gatekeeper in the copyright world.

This article explains these indirect benefits in detail and explains a strategy for telcos to adopt in the online video world.

A rising tide raises all boats

On a macro level, the more ‘eyeballs’ and time spent on the internet, the bigger percentage of advertising budgets that advertisers will allocate to internet marketing. Compelling content is an essential attractor of ’eyeballs’. For Google with its massive share of the internet market, it doesn’t matter quite as much whether the video stream itself is monetized today as long as it picks up a share of the increase in the overall digital advertising budget.

Video viewing is becoming increasingly significant: 78.6 percent of the total US internet audience viewed online video. The average online video viewer watched 385 minutes of video, or 6.4 hours.

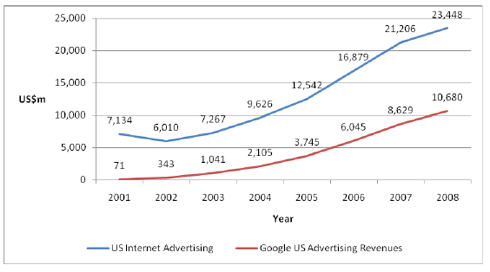

And Google’s share of the Advertising Pie keeps on rising.

Source: IAB/PWC Data and Google SEC filings

How much revenue does YouTube contribute? Unfortunately, Google's does not publish these figures. Credit Suisse in their infamous analyst note estimates YouTube 2008 advertising revenue at only US$200m (associated with overall losses of US$470m) and the IAB/PWC data estimates video advertising at only three per cent of the overall internet advertising market.

A social network by stealth

One of the little discussed benefits of Google owning YouTube is that YouTube is more than a pure video streaming network. It is a social network in its own right. Accounts are needed to create, comment about and rate content, which is something that is not required for the core search service.

It is hard to envisage that at this stage YouTube is directly monetising this meta-data. Undoubtedly, however, it will be contributing to understanding of user-behaviour, and probably the data is already contributing to the optimisation of the Google advertising engine.

Google's economics are extremely difficult for competitors to replicate and represent a significant barrier to entry.

Google worldwide revenues have grown by US$11.2bn to US$21.8bn in the two years since purchasing YouTube in 2006 for an all-share cost of US$1.8bn. In the same period, operating cashflow has grown by US$4.3bn to US$7.9bn.

The amount of indirect contribution of YouTube to Google revenues is uncertain, but what is more certain is that Google can afford YouTube.

The real economics of YouTube

One of the most important disciplines of internet economics is to keep the marginal costs of delivering another page or another video stream as close as possible to zero. With YouTube,the key variables are computing and bandwidth costs. Google’s tactic is turning the majority of them into capital costs. Google is deploying more and more capital building out infrastructure, whether vast data centers or its own network - effectively keeping an ever-increasing proportion of its traffic on the Googlenet.

Another key variable costs for YouTube is the cost of the content itself. Google here attempts to minimise its risk by making any payout to third parties dependent upon success of advertising revenues achieved. This is the cornerstone of the Adsense program for publishers. Unfortunately for Google, it is not the traditional way that the video content industry works and therefore is a great source of friction between YouTube and video rights holders.

The Bandwidth Equation

A case can easily be made that Google could make its cost of delivery for video zero. Every global IP transit provider would love to be the exclusive deliverer of such a significant portion of the world’s Internet traffic, and the transit providers could make money by squeezing the downstream ISPs in their cost of delivery. Such an extreme network design would bear a heavy political cost for Google and would obviously be unpalatable, but it illustrates the power that Google has accumulated through the YouTube traffic.

Instead of focusing on IP transit, Google extensively uses peering, delivering its own traffic to the major peering points in the world, as we made clear in this post, which the people at RampRate used in their critique of Credit Suisse. Peering is not free - it involves buying expensive dark fibre linking the Google data centres to the peering exchanges, renting space in the peering exchanges, equipment to light up the fibre and a team of network engineers to manage the peering relationships. However, most of these costs are fixed. As important for Google is that peering will allow them to control the reliability of delivering their traffic.

Look out, Akamai

A more recent tactic for Google is to build edge-caching servers within ISP networks bringing the content closer to the end-user and thereby improving the speed of delivery. The early indication seem to be that Google is building its own content delivery network in much the same way as Akamai has built one - except that the Google one is for internal use only, right now.

Most media companies have to use third party content delivery networks, as they don’t enjoy the Google economies of scale. For instance, the BBC uses Akamai for delivery of a significant proportion of its traffic. The Google costs are fixed whereas the BBC’s are variable - it is paying a third party supplier.

The more difficult question to answer is how much the sheer volume of YouTube traffic is helping the other Google services, especially the highly profitable search business. Significantly, we would argue - in terms of cost, reliability and speed. Furthermore, the overall bandwidth economics that Google enjoys are extremely difficult for competitors to replicate and represent a significant barrier to entry.

The Google strategy in distribution seems to be to keep control and only outsource the minimum. Logically, Google would only adopt this strategy if it felt it could gain a competitive edge through distribution. Scale matters in distribution and YouTube brings that scale to Google.

Despite BT claiming that the BBC and YouTube are enjoying a free ride, the exact opposite is true.

Video on the internet is currently extremely difficult to monetise - as we say in the Telco 2.0 Online Video market study, we are currently in a “Pirate world” where most content is available is available for “free” from a variety of sources. Old media are seeing their revenues cannibalised as content moves online into the “Pirate World”.

Eventually, either through legislation or sheer volume of eyeballs, New Players will emerge whose revenues and profits will be significant. Arguably, the effort to increase the percentage of YouTube videos that carry ads is a key indicator of this. The business model for this New World is still extremely uncertain. However, just because of the sheer volume of traffic, Google will have a key seat at the value chain negotiating table. Google will also almost certainly be the lowest cost player, in both aggregation and distribution.

Cutting out the middle man

What would make the negotiating position of Google even stronger is control of the method of licensing content. The recent Google Books deal shows that Google is starting to get extremely interested not only in the meta-data around copyright, but also in distributing payments directly to content creators and not through traditional aggregators.

In this case, the creators are the authors and the aggregators are the publishers. It does not take a major leap in thinking to see how Google could disintermediate the traditional aggregators of video and music with YouTube.

In the future, YouTube will be the key for Google establishing a strong position in the licensing of media content and thus not only controlling its own costs, but being a critical aggregator and distributor for content owners in its own right. Google will try to turn its current Achilles heel, copyright, into a future strength.

Despite BT claiming that the BBC and YouTube are enjoying a free ride, the exact opposite is true. Google is building out both compute and bandwidth infrastructure for delivery. Other video services, for example the BBC, are paying third parties such as Akamai for distribution

The real battleground is around the share of the value chain. BT is really saying that it is not earning enough from its access fees and the economic table is tilted in the favour of “free-at-the-point-of consumption” video services such as YouTube and other sites, such as Hulu and the iPlayer.

But all is not lost.

The growing size of the payTV market proves that advertising alone cannot fund all video services, and that consumers will pay for premium content. The core strategy for telcos competing is not to replicate YouTube, but by providing tools for the myriad of content owners who are unhappy with the current payback from the online world - these tools are not limited to billing and payment services, but should also include copyright protection.

The war of online value chain is not yet lost: we are still in a pirate world, and Google is one of a very small club who can afford to distribute all types of content across the globe. ®

[A longer version of this analysis appears at the Telco 2.0 Blog.]