Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2009/03/13/rashid_innovation/

Microsoft's R&D chief: the people problem with innovation

iPhone's secret father speaks

Posted in OSes, 13th March 2009 00:17 GMT

Updated Rick Rashid, leader of Microsoft's R&D operation, said he could foresee cloud computing some years back.

The challenge as a technologist, though, has been in anticipating the finer details of how the cloud and its related technologies - the data center, replication, and synchronization - will be adopted by people and organizations.

Sure, Microsoft was heading in that direction in the labs, but Amazon, eBay, and Google got there first in their businesses, and Microsoft is now fast trying to catch up.

Speaking to The Reg at Microsoft's Mountain View, California campus recently, Rashid outlined the challenge: "What I've never been very good at - and don't think anybody's that great at - is knowing what society is going to do with them [technology innovations]. That's the harder part."

As a professor at the Carnegie Mellon University, Rashid helped in the creation of the Mach kernel. That early work speaks to the challenge. Mach was intended as replacement for BSD and Unix but has snuck into Apple's orgasmically successful iPhone.

Rashid: technology prediction will get you so far

"Did I realize in the early 1980s that the operating system I was building would someday run on a cell phone. I'd have said: 'What's a cell phone?' - they didn't exist. So you never really know what's going to happen or how something that you've created is going to be eventually used and what forms it's going to take. Technologists are never good at that kind of prediction."

After joining Microsoft in 1991, Rashid patented work in data compression, networking, and operating systems that helped turn Windows into the multi-billion dollar gift that keeps giving to the Microsoft bottom line.

That track record's important given that the 850-person R&D operation Rashid now runs is working on search, social computing, and systems architecture and is getting a share of the company's overall $9bn research-and-development budget thanks to chief executive Steve Ballmer's enthusiasm for beating Google online and easing Microsoft's reliance on the PC.

The work of Rashid and others on his team might yet turn Microsoft's nascent cloud into a multi-billion-dollar business akin to Windows - despite its lateness and early mistakes.

Microsoft was forced to announce a major U-turn on cloud-based storage this week after it succumbed to its usual product-segmentation fever, but the company's already got the fundamentals in place with data centers and a core-computing fabric that it can build on. And that's a lot more than some others have, who are still at the talking stage.

Rashid is certainly optimistic. "There's been a huge impact on the business of the company, and the products we ship," he said of the R&D operation. "We've been creating $1bn businesses every few years over the last 10 years."

Asked if he foresaw the rise of the cloud as a successor to these $1bn businesses on the desktop and server, Rashid indicated he thought Microsoft was moving in the right direction.

"There are two ways to answer that. The first is to say 'yes' - I've got slides," he confessed. "One of the things you see in any research environment is you get to see the technologies people are developing, you can make summaries about what people doing with them, you can put them in slides.

"Did we know we could build these big data centers...were we thinking about the services mesh? Yes, absolutely," he said.

"Did we know it was going to pan out in a particular way. Did we know what's happening now with the shift to cloud services and the way businesses are thinking about large-scale computation? No. The exact details of how things pan out have to do with society, legal and government environment, and business climate. But were all the seeds there? Absolutely."

The patent question

Microsoft unlike some companies in the tech sector puts a lot of value in R&D. That doesn't make the work any easier, though. Working on new ideas takes courage to commit from an early stage to something people may not yet get or that seems relatively unimportant, according to Rashid.

"You have to have courage especially in the beginning," Rashid said.

"In the beginning, you don't know what's going to work. We've been going almost 18 years and get feedback from all parts of the company saying: 'You guys are doing great stuff,' but the problem is that's at the end of the pipe - they are seeing stuff the researchers were first thinking of years ago. Once the pipe's full this is great, but in the beginning the pipe is not full and that's what takes courage and some suspension of disbelief."

Interestingly for someone who's chalked up a fair number of his own patents, and who works for a company infamous for its love of patents, its desire to make money from those patents and willingness take others to court to enforce its patents, Rashid seems to depart from the party line on the actual value of patents.

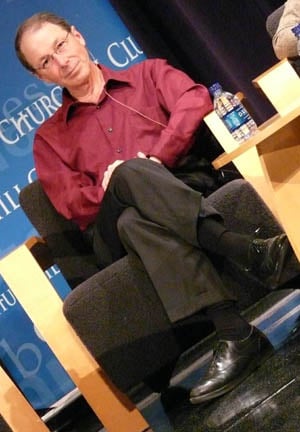

He thinks patents are a poor way of measuring the rate of innovation or progress. That quickly became clear during a Churchill Club debate hosted by Microsoft at its campus last week about the importance and role of R&D during the current economic "crisis."

Rashid disagreed passionately with fellow panelist Josephine Cheng, a vice president and research fellow with patent hits factory IBM. Microsoft is trying to compete with IBM on how many patents it can register, while IBM actually rewards its staff for filing patents.

Remonstrating with Cheng, who'd said patents are one yardstick for measuring the rate of innovation, Rashid said: "No, that's a horrible metric. The number of patents is a measure of how much you want to spend on lawyers!"

Rashid to Cheng: patents a "horrible metric"

Also, throwing wads of cash at a problem is not just shortsighted when it comes to the subject of encouraging innovation, Rashid believes it can actually hurt progress. Rashid said his pet peeve is the earmarks that are common in the US government, where politicians attach to legislation spending on projects they have a vested interest in for their district.

The problem is that while earmarks might mean money for technology in the short term on special projects, such as a research facility in West Virginia or Southern California, they do not represent long-term investment or commitment.

"We've done things in the past, where we made large investment, say, for example, in aerospace and we've just stopped, and as result a lot of people said: 'I gotta find a job somewhere'. And as a result you lose a generation of people, then 10 years later you say: 'Hey is there anybody here knows how to solve this problem?,' and the answer is 'no', of course, because everybody's left."

Rashid hopes the new Barrack Obama administration will change things at a national level and also invest in innovation through the stimulus package by setting out a long-term plan of sustained spending in science and technology. Healthcare looks like being one particular beneficiary.

The challenge lies in breaking the cycle, by getting people to stop accepting the money in the first place and to invest time and effort, even if the technologists can't clearly see where their work will head.

"When I went to Microsoft and started at Microsoft research everybody understood that would be along term commitment," he said. "Science isn't like building roads or bridges. It's really about trying to reward the smartest people," he said. ®