Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2008/12/11/engelbart_celebration/

The Mother of All Demos — 150 years ahead of its time

It’s not the mouse. It’s what you do with it

Posted in Software, 11th December 2008 06:10 GMT

Sometime in the late sixties, as Douglas Engelbart was preparing what would one day be called The Mother of All Demos, his boss flew to Washington to meet with the money man.

The demo that birthed the modern computer mouse - and so much more - was funded by Bob Taylor, a NASA program manager who would one day take his own place among the titans of modern computing. Engelbart's boss had a single question on his mind as he walked into Taylor's office after a cross-country flight from Northern California's Stanford Research Institute.

"He came from the west coast to see me, which was very unusual," remembers Taylor, also known for cooking up the ARPAnet and Xerox PARC's Computer Science Laboratory. "He came into my office and he said 'I want to talk to you about Doug - Why are you funding this guy?'"

Needless to say, Douglas Engelbart's boss wasn't the only one who questioned the import of the mouse inventor's 1968 interactive-computing demo, which received a 40th anniversary celebration at Stanford University's Memorial Hall yesterday afternoon. Bill Paxton - one of the SRI researchers who participated in the demo - says that 90 per cent of the computer science community thought Engelbart was "a crackpot."

"It's hard to believe now," he explains, "but at the time, even we [Engelbart's fellow researchers] had trouble understanding what he was doing. Think of everyone else out there."

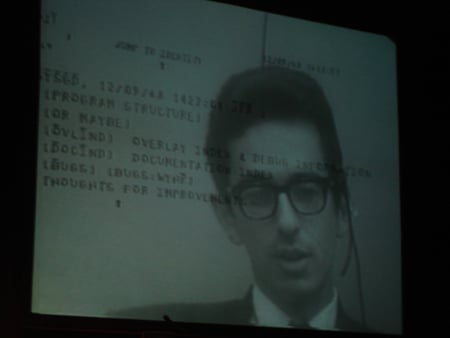

The Demo Relived

Three or four years later, Engelbart repeated his hypertext-meets-desktop-sharing-meets-video-conferencing demo. In the audience was an MIT prof described by Andries van Dam, another east-coast prof in attendance, as among "the best and the brightest" of the early 1970s computing cognoscenti. According to van Dam, at the end of the presentation, the MIT man raised his hand and said "I don't get it - everything you've shown me today I can do on my ASR-33."

The ASR-33 was a standard-issue teletype - a machine that did nothing but print stuff you keyed into it. "In a Turing sense, he was right," van Dam says. "But that was completely not the point. The demo went right over his head, and I thought to myself, 'If the best and the brightest can't grok this, what hope have we got?'"

As it turns out, there was hope. In the years to come, Engelbart's on-line system - known by the pseudo-acronym NLS - begat the GUI machines developed at Xerox PARC. PARC begat the Apple Macintosh. And the Macintosh begat a widely used operating system from a company called Microsoft.

Engelbart didn't just invent the mouse. He and his team were the first to divide a graphical interface into windows-like subsections. "Even way back then, we already had the concept of multiple windows," Engelbart told The Reg in 2005. "Any one application could manage multiple windows, and you could easily move objects, paragraphs, and words between them."

Desktop sharing, 60s style

NLS also foreshadowed video conferencing and desktop sharing, as Engelbart demonstrated for Andy van Dam and about a 1,000 other computer obsessives on that December afternoon back in 1968. At yesterday's 40th-anniversary celebration, Engelbart's colleagues and peers gathered to hail him as one of computing history's great visionaries - a man who foretold the future.

"[Engelbart] was one of the very few people very early on who were able to understand not only that computers could do a lot of things that were very familiar, but that there was something new about computers that allow us to think in a very different way - in a stronger way," says Alan Kay, the PARC researcher who built atop Engelbart's work with the development of the object-oriented computing environment he called SmallTalk.

But those gathered for Engelbart's anniversary also warned that most of his vision was lost amidst the computer revolution.

A Dream Deferred

As van Dam points out, Engelbart's system seamlessly combined its tools in ways our modern machines do not. "[NLS] hasn't really been realized with the mainstream market," van Dam says. "We're looking back at this with a kind of nostalgia, asking what this magician did for us. But ask yourself this: What do we really have today?

"We have a collection of tools at out disposal that don't inter-operate. We've got Microsoft Word. We've got PowerPoint. We've got Illustrator. We've got Photoshop. We can do a lot of individual things that were done with NLS and we can do them with more functionality...But they don't work together. They don't play nice together. And most of the time, what you've got is an import/export capability that serves as a lowest common denominator."

For van Dam - and others who witnessed it first hand - NLS went much deeper than the GUIs of today. "Everything inter-operated in this super rich environment. And if you look at the demo carefully, it's about modifying, it's about studying, it's about being really analytical, and reflecting about what's happening."

This last point is hammered home by Alan Kay, another firsthand witness to Engelbart's 1968 demo. "I was shivering like mad, with a 104 degree temperature," he says. "But I was determined to see it."

Engelbart and fans

When Kay thinks of NLS, he remembers Henry David Thoreau's response to the first transatlantic cable. "We are eager to tunnel under the Atlantic and bring the Old World some weeks closer to the New," Thoreau wrote in Walden. "But perchance the first news that will leak through into the broad, flapping American ear will be that Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough."

Kay calls this "one of the earliest examples of capturing the two sides of technology. Here's this incredibly difficult technical feat that could be used for expressing important information back and forth. But Thoreau understood exactly who human beings are and what they like to do with their technology."

Like van Dam, Kay argues that Engelbart's interactive system hasn't been realized. "You may have noticed after watching the demo that [NLS's] response time is a just a little bit better than we have today." But his bigger point is that the ideas that did survive are now dedicated to transmitting the 21-century equivalent of Princess Adelaide's whooping cough.

NLS wasn't meant to enhance the transatlantic cable, Kay says. It was meant to create an entirely new form of collaboration. "It showed that ideas could be organized in a different way, built in a different way. What we were looking at was not something that was trying to imitate what was already there.

"The jury is still out on how long - and whether - people are actually going to understand this." It took the world 150 years to realize the true power of the printing press, Kays says, citing Thomas Paine's Common Sense as the publication that finally did the trick. And he wonders if we will need another 150 years to embrace NLS.

NLS was designed to harness the power of "collective intelligence" - to create a deeper level of thought. His research group was dedicated to "augmenting human intellect." But forty years on, Engelbart's core vision has vanished. NLS has devolved into Twitter.

But Kay still has hope. "We haven't forgotten NLS, after 40 years. It's as good today as it was when we first saw it. The real significance of NLS is that it put a difficult idea into the world and it put it into the world so well that none of us can forget - and everyone will leave here today and go out and try to get others to understand it." ®

You can view The Mother of All Demos here.