Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2008/06/23/marginal_browser_security_protections/

Web browsers face crisis of security confidence

Good enough for Donald Rumsfeld. But not for you

Posted in Channel, 23rd June 2008 21:56 GMT

User beware. Today's web browsers offer more security protections than ever, but according to security experts, they do little to protect people surfing the net from some the web's oldest and most crippling threats.

Like nuclear stockpiles during the Cold War, new safety features amassed in Firefox, Internet Explorer and Opera are part of an arms-race mentality that leaves online criminal gangs plenty of room to launch attacks. What's more, the new protections often take years to be implemented and months to circumvent. Meanwhile, shortcomings that have bedeviled all browsers since the advent of the World Wide Web go unaddressed.

Earlier this week, Mozilla patted itself on the back for adding a security feature to Version 3 of Firefox that's of only marginal benefit its users. It prevents users from accessing a list of websites known by Google, and possibly others, to be spreading malware. Opera Software, in a move its CEO proclaimed "is reinventing Web-based threat detection," added a similar feature to version 9.5 of its browser released two weeks ago, and Microsoft engineers are building malware blocking into IE 8.

Here's the rub: According to our tests over the past week, the Firefox anti-malware feature frequently failed to block sites compromised by one of the most prevalent SQL injection exploits menacing the web. Outcomes varied from minute to minute, but clicking on results returned from searches such as this and this (we strongly recommend you don't try this at home) led us to dozens of compromised websites even with Firefox's gee-whiz malware protection feature turned on.

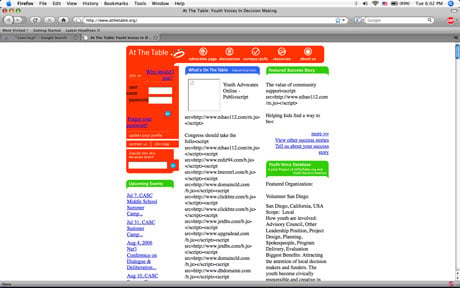

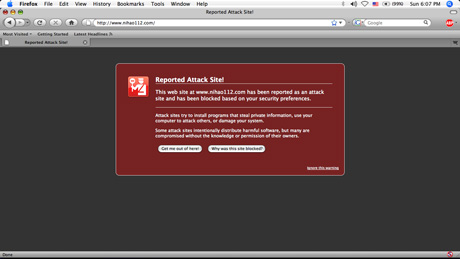

Firefox 3 does block nihao11.com and the half-dozen or so other domain names that are referenced in the injection attack, so there is some benefit to the feature. But its inability to flag a huge number of websites that have been compromised shows the limits to such an approach. Similarly, researchers from Websense report here that they "found multiple phishing pages that still made it through" anti-phishing mechanisms that have existed for more than a year in Firefox. Because they're based on static blacklists based on behavior reported weeks or months earlier, these features often fail to detect quick-moving threats.

"These little anti-phishing things and anti-malware things, I'm not buying them," says Jeremiah Grossman, CTO of web application security firm WhiteHat Security. "Are we less likely to get hacked as a result of these features? No. If I was really the evil guy, I'll send you to a hacked up blog page with Firefox 3 and you won't have a good day."

Still waiting for Firefox to flag this site as a malware pusher

Meanwhile, within hours of Firefox 3 being released, researchers reported a security bug that could allow miscreants to execute hostile code on machines running the new browser.

Like IE, Opera and every other browser on the planet, Firefox also remains vulnerable to a variety of attacks that are as old as the World Wide Web. They allow miscreants to inflict all kinds of damage, including stealing a user's browsing history, spoofing trusted websites through cross-site scripting attacks (XSS), stealing user authentication credentials to banking sites and providing easy access to corporate intranets and end-user machines.

Of course, browser makers are by no means alone in shouldering responsibility for these weaknesses. Sharing equal amounts of blame are the eBays, MySpaces and Facebooks of the world for failing to resist the allure of untested features based on Adobe Flash and JavaScript, even when they deliver only minimal convenience over more traditional methods of delivering content. Also culpable are netizens everywhere, who collectively reward all these websites for adding bells and whistles that put our safety in jeopardy.

"I wouldn't tell you not to use the internet, but I would certainly never tell you you're safe, which is a pretty horrible thing to say to someone," says Robert Hansen, CEO of secTheory, a security firm that specializes in security of web applications. "I really don't think people are in a good position from a technology perspective to defend themselves with what they're given by default in a browser."

Crisis of confidence

The situation is so dire in the minds of many security experts that they no longer trust any browser to keep them safe without taking extraordinary security measures. Grossman, for example, uses Firefox with the NoScript, Flashblock, SafeHistory, Adblock Plus and CustomizeGoogle add-ons for most of his web surfing, all to improve on the less-than-ideal state of today's web. When visiting financial sites, he switches to an obscure browser that he refuses to name. By treading off the beaten path, he says, he's less likely to get hit by an exotic zero-day exploit, which can sell on the underground market for tens of thousands of dollars if it targets a popular browser.

The obscure browser "is technically not more or less secure, it's just less targeted, which is the only thing I care about," Grossman says. As extreme as it may sound to some, Grossman says his browsing regimen is less hardcore than other people he knows in the security industry. Indeed, some of the more paranoid have entire physical machines reserved solely for sensitive transactions, employ boot-only browsers via CD-ROMs, or use virtual machines with limited features for the same purpose.

"I have very low confidence in any of the browsers' ability to keep me safe," says Don Jackson, a researcher with security provider SecureWorks. "What I have confidence in is the bad guys." One of the chief problems Jackson identifies with browser design these days: "Functionality is implemented first and security is tacked on."

Next page: 'You go to war with the army you have'

The crisis of confidence begs the question: Just how did things get this bad, anyway?

'You go to war with the army you have'

In late 2004, then US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld faced growing criticism for his decision to send US soldiers into combat with Humvees that were ill-equipped to withstand blasts from roadside bombs. When confronted by a soldier in Kuwait who complained that a shortage of armor forced him and his comrades to root through junkyards for scraps, Rumsfeld replied:

"You go to war with the Army you have, not the Army you might want or wish to have."

His point - that in the real world, professionals often have to make do with an imperfect situation created by forces out of everyone's control - couldn't be more applicable to the hard-working men and women at the helm of today's internet.

The Arpanet's underpinnings may have been built to withstand a nuclear blast, but they were never designed to competently perform even basic tasks such as authenticating an email sender as a particular person. The arcane RFCs that it soon spawned relied on the most primitive of methods to deliver text and graphics that left users fairly uninspired once they got over the novelty that the net's reach was virtually ubiquitous and instantaneous. Add to that a domain name system that enables an array of attacks and it's obvious the internet was never designed with security in mind.

It was in this highly flawed world that Netscape Communications, eBay and the rest of the net pioneers found themselves racing to build billion-dollar businesses that required complex webs of trust. Suddenly, technologies that had no grounding in security were being used to handle all kinds of sensitive information. Cookies were being used to authenticate users on banking websites, flimsy Ajax scripts held the keys to executive's calendar entries and email messages and an overabundance of buggy ActiveX programs was relied on to fill the considerable gaps left by websites that did little more than deliver static text and pictures.

The situation grew especially dire starting in the late 1990s, as Microsoft, in a series of steps later adjudged to be illegal, snuffed the life out of Netscape's Navigator browser. A lack of genetic diversity and Microsoft's then deep-seated inattention to security resulted in the years to follow being a particularly dark period for web security. Parasites like Nimda, Slammer, Code Red and Blaster wreaked havoc on businesses big and small and firmly cemented the net's reputation as a Darwinian place where the weak get preyed upon.

Things have thankfully improved since then. The rise of Firefox and Opera gave users a viable alternative to the IE hegemony, making it significantly harder for criminals to write a single piece of code that will work across wide swaths of the internet's user base. More importantly, the new browsers made it easy to control some of the net's more reckless technologies by steering clear of ActiveX, and fostering third-party extensions such as NoScript, which allows users to choose which sites get to run Java, JavaScript, Flash and iframes.

"We're asking a lot of a piece of software to take code anywhere on the internet and execute it on a user's machine and not interfere with the machine," says Mozilla's security chief Window Snyder. "People want to browse the web. They want to have these rich Web 2.0 experiences. It's a lot safer now than it used to be."

The safest browser?

Mozilla is fond of calling Firefox "the safest web browser." Given Microsoft's checkered past, and the speed with which Mozilla patches reported security flaws, that's probably true. But it's worth noting that for all Mozilla's preening the open-source organization has yet to release a browser that runs in so-called protected mode. The idea is to isolate the browser from the rest of the operating system to minimize errors that could otherwise allow attackers to hijack the machine running the program. Because exploits such as buffer overflows are relegated to a virtual sandbox, they remain dormant because they never get the opportunity to make changes to the OS at large.

Firefox's New malware protection

Internet Explorer 8 running on the Windows Vista operating system, by contrast, does offer this rather sensible piece of protection. Snyder said Mozilla considered adding the feature to the recent release but ultimately decided against it.

"It's a pretty significant change," she said. "It just didn't fit into Firefox 3." She said Mozilla may fold the feature into an upcoming version.

Read on to learn about the scourge of the ActiveX shrew

Whatever its faults, Firefox wasn't the browser that brought us ActiveX and therein lies the key reason it has stood up so well when compared to IE over the years. Last year, there were some 339 vulnerabilities in one or more ActiveX controls, according to security bug tracker Secunia. That compares with about 35 flaws in QuickTime, 12 in Java, 12 in Flash and 6 in various Firefox extensions. What's more, ActiveX bugs tend to bite harder because Microsoft designed ActiveX to have much greater control of the underlying operating system than Java and most other browsing components. As a result, ActiveX for years became a cornerstone of the underground malware industry.

"Too many ActiveX controls are of poor quality and haven't been through a quality assurance process and security audit before they're published," Thomas Kristensen, Secunia's CTO says. "A lot of them are inherently insecure and of very poor quality, which makes it easy for the bad guys to find vulnerabilities."

Microsoft choked off much of the most pernicious ActiveX threats four years ago with the release of Service Pack 2 for Windows XP, which made it much harder for miscreants to use the controls to silently install malicious code on end users' machines. And changes in IE 8 previewed here (click "Peace of Mind," then "Browser-Based Exploits") promise users "greater control over who can install Microsoft ActiveX controls and on which sites the ActiveX controls are allowed to run." (The site promises a host of other improvements, including data execution prevention that is turned on by default and features known as Cross Domain Request and Cross Document Messaging to ward off attacks on web servers.)

Cookie mishmash

In addition to largely taming the ActiveX shrew, Microsoft over the last few years has adopted a tireless security posture that places a high premium on communication and patching vulnerabilities within a reasonable amount of time, and that's gone a long way to making people safer.

"IE 7 is a very secure browser," Jim Hahn, a member of the IE team says. "A machine that is fully up-to-date is very secure, and we feel very confident about that."

Last page: As the net burns, browser makers fiddle

But while the browser makers and web application developers continue to add improvements around the edges, the most glaring and menacing vulnerabilities remain untouched. For more than a decade, for example, browsers have made it easy for unauthorized people to access corporate intranets and other off-limits areas by linking public IP addresses with those cordoned behind a firewall. This opens up all kinds of nasty possibilities, including intranet port scanning, which can reveal weaknesses in corporate networks and drive-by pharming, in which attackers use a victim's browser to change crucial home router settings. Browsers have long been able to contact a PC's inner IP address known as the localhost, an ability that's essential for programs like Google Desktop to work, but also one that unnecessarily exposes huge amounts of a machine's most sensitive innards.

At fault is the net's lack of what's known as zone separation, or a mechanism for classifying some addresses as public and others as private. Designers of the Arpanet never designed the mechanism into their creation, and no one has bothered to try since.

The net also lacks a robust way to authenticate users or reliably establish secure communications channels between trusted websites and end users. As a result, each bank, ecommerce site and online broker offers a different mishmash of authentication cookies, session log-outs and one-time tokens to establish their customers' identities. And secure sockets layer, while proving surprisingly versatile in preventing man-in-the-middle attacks, has its own Achilles Heel that net architects have ignored for years.

Don't count on many of these flaws getting repaired anytime soon. Despite its lack of a foundation, the net has proved adept at supporting a dizzying number of frameworks, many that were designed to work on top of the old, buggy ways of doing things. Fixing many of these long-standing flaws will have the unintended consequence of breaking major parts of the internet. It's a little bit like digging a cellar for a 10-story building.

Tackling the problem will also require representatives from hundreds of companies to come together to forge new standards to replace the old ones. So far, no one at Microsoft, eBay, Mozilla, Cisco or anywhere else we're aware of is showing much leadership in marshaling their peers to arrive at a industry-driven solution, so the old, broken methods are allowed to continue year after year.

From the Department of Big Lunches

About the only hopeful sign we've seen is a highly experimental set of security protections that Firefox developers have been tinkering with. First reported here, the technologies insulate users against two broad classes of attacks. One would minimize exposure to XSS and cross-site request forgery attacks by allowing site developers to define which domains are allowed to initiate or answer cross-site requests for code, cookies and other site resources. A second would guard against so-called DNS rebinding attacks like those researcher Dan Kaminsky has demonstrated.

For now, the protections will largely be implemented as a Firefox extension that will serve as a proof of concept. Depending on how they're received, they could blossom into open specifications that website developers could use to enforce policies across any participating browser.

Short of Mozilla's noble experiment, browser makers, web app developers, network providers and others shaping the direction of the internet have shown woefully few signs they're ready to confront the significant challenges they've inherited. Instead, they make incremental security improvements and pass them off as achievements on par with the cure for polio.

And then they make excuses for not doing more. Eventually, the world's net users will grow tired of this course of action, and the net's architects will run out of time. Just ask Donald Rumsfeld. ®