Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2008/05/26/paul_sanders_digital_flops/

The music biz's digital flops - a short history

Beware of The Next Big Thing

Posted in Legal, 26th May 2008 12:02 GMT

Since the record industry first noticed that some of the kids were using the internet in the mid-90s, it's flopped from one puddle to the next. Despite a desperate need to evolve - guys, the pond is drying up, do try to breathe - recording industry strategy has flopped from one muddy puddle to the next, and a muddy puddle is quite a good metaphor for the latest survival strategy: advertising supported music which 'feels like free' to the consumer.

Flop, flop, flop. So let's take a quick tour of the puddles, in rough chronological order.

The first muddy puddle was all about marketing the album and adding value to the CD. These were heady days for web developers when a label could be persuaded to part with upwards of £50,000 for a website with a few bits of repurposed server-side code or client side Flash. Alongside this were the first experiments in enhanced CDs and brave but foolish 'multimedia' projects. The multimedia arms race - you can get a flavour of it from this announcement by EMI in 1995 - took a few years to prove itself expensive and largely pointless. Music CD-ROMs couldn't compete with games, and were subject to the explosive and expansive egos of artists as budgets ballooned and projects failed to be delivered. Websites got heavier and more 'creative', again to stroke egos rather than feed fans.

And the upshot was that by the late 90s, record labels were paying out more than the price of a CD to reach each and every person who had already bought the CD anyway. Which led some of the more commercially driven execs to start to think of the net as a sales and distribution channel.

Diamond Rio MP3 Player

And just for context, the MP3 format had hopped off alt.binaries and Hotline and onto the web in 1998 gaining sufficient popularity for Diamond Multimedia to risk marketing a hardware player, the Rio, which played MP3s. Which the RIAA failed to kill at birth, as an instrument of infringement.

SDMI

So into the next puddle we flop, and this one is inhabited by SDMI and friends. The lesson is that cake is not a dual-use foodstuff. The central idea that motivated the participants was to produce a kind of technical environment that would allow consumers to access only approved music, and would allow record labels to decide even post-distribution what could be done with it.

They thought big.

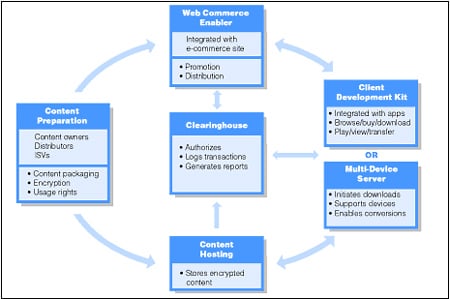

SDMI at its peak was a consortium of around 200 member companies and churned out technical documents under the fervent leadership of Leonardo Chiariglione, an MPEG expert and in 1999 number 19 on Time's top 50 digital movers and shapers list. Fellow travellers included EMMS, from IBM, otherwise known as the Madison Project, and bluematter, a proprietary multimedia packaging format from Universal Music Group.

Anyone remember Universal's Bluematter?

It was in these cauldrons that 'Digital Rights Management' principles and techniques first flavoured the music retail stew, and companies such as Macrovision started punting around CD copy-protection malware.

IBM's ambitious Madison project

But they were all predicated on Napster being shut down and nothing taking its place, which with hindsight looks a little over-optimistic. The blowtorch of decentralised P2P, the continuing popularity of the plain old CD (it's rippable), and consumer indifference to the massive and clumsy software they were being told they would have to use if they wanted music, all contributed to drying up the puddle. Needing to follow the consumer, technology industries en masse adopted MP3 as the standard format. SDMI fell apart, Madison was shelved.

Label-owned stories

So as the mud started to crack, flop went the recording industry into the next puddle, which in retrospect looks like an episode from TV's The Good Life. The record companies attempted self-sufficiency while their bemused technology neighbours looked over the fence.

So, in 2001 Universal was ready to announce Duet, its exclusive licensing partnership with Sony, to push its own aforementioned bluematter file format on as many unfortunate retailers as it could corral. And shortly after, RealNetworks put together a consortium of the other major labels and announced MusicNet, to do much the same.

Here's the counteraction: 2001 was the year of Apple's 'Rip. Mix. Burn.' campaign, as it added a CD-RW drive to the already iconic iMac home computer.

The labels whinged, of course, and while 'fair use' got its first real public airing in the press, the hipper recording execs started talking about downloading CDs to your computer and ripping the files to your MP3 player. Language is a window on the soul sometimes. The public was so excited by their new freedom with music, that when Apple launched the iPod the brand name was immediately genericised, like the hoover and fridge before it. And recording execs - now looking slightly less hip - started pointedly referring to 'MP3 players': meaning any device which could decrypt Windows Media DRM.

It took just over a year for RealNetworks to realise that record companies were - to bring the Good Life analogy to a climax - unable to recognise a goat, let alone milk one or turn it into curry pasties, hopping back over the fence to rejoin the technologists and announcing that the future was in its own subscription service, Rhapsody. Spotting another muddy puddle, the record strategists flexed their fins and went for it.

Enter iTunes

In bubbleworld, consumers are so delighted with having four million tracks in one software application, and being able to make playlists for themselves and maybe listen to pre-programmed streams, that they can no longer see why they would ever want to 'own' music. (The music industry has always told them they don't own music anyway - Todd Rundgren once referred to a CD as a 'licence to listen in the form of a plastic disc'.)

2002 saw the launch by the record labels of a brace of subscription services that would later make PC World's Top Ten Worst Tech Products of All Time, MusicNet and Pressplay (the surfacing of the Sony/Universal Duet deal). Outside of bubbleworld there are iPods, and CDs and loads of MP3s; imagine a small underpowered horse behind a large motorised cart.

The cart was just getting warmed up. The iTunes store was launched in 2003, and just five years later is now the biggest music retailer in the US. But strangely it never looked like a muddy puddle to the strategy execs. Perhaps it was too simple, offering 'buy to own' at a fixed price. iTunes' launch year also saw the beginning of the ringtone sales curve hockey stick.

Heave, flop.

Someone who made a lot of money out of it recently told me that in his view the record company strategists had entirely misunderstood the nature of the ringtone market. He said, it's 'bling' - cheap jewellery, not music.

Mobile: Always the next big thing

One of the interesting features of the evolution of digital music is how the optimistic forecasts spring up like desert flowers after the rain of a strategic shift. A cynical observer might think that those strategists were using their research budgets to support their pre-conceived notions rather than to test them.

Quoting them were those very record company strategists who only months before had been investing their credibility in PC subscriptions, tethered or 'to-go'. Now they hit the conference circuit, waving their complimentary mobile phones at audiences.

By now, anything which looked even remotely incremental was being called a 'lifeline' by the analysts and journalists, and mobile fitted the bill. But after almost a decade of generating strategies, and watching the internet music investment boom and bust, a weariness seemed to be setting in.

Thus it was perhaps that most mobile action in the middle of this decade amounted to a bit of licensing, and an expansion of the number of SKUs that went around a record release. Only Amp'd Mobile in the US could really be characterised as a big bold bet with an investment from Universal Music Group, the largest of the majors. The trajectory of the recording industry's belief in mobile can be tracked by proxy in the fortunes of a small French company called Musiwap.

Recently-defunct MVNO, Amp'd Mobile

Musiwap started doing local deals in 2001, found investment and became Musiwave in 2002, got bought by Openwave for $121m in 2005, and was sold by Openwave to Microsoft in 2007 for $46m. Amp'd declared itself bankrupt in 2007, having munched through $360m.

Of course while none of the strategic geese have shipped gold, none has gone away either, and each has been assimilated into normal business for the recording industry. And that will no doubt prove to be the case for the next puddle - advertising-supported music.

Ad-supported music

It would be very gratifying to be able to say that this rise in expectations for advertising cash was a mature response to new marketplace evidence that some of the new entrants to consumer music services were actually delivering revenue in convincing quantities and in a scalable manner. But I can't, because they're not. Most have yet to launch in any significant way.

Accenture recently released its yearly survey of top content execs, and about two-thirds of them are looking to advertising to drive the funding of content creation. That's up from the 50 per cent that said the same in 2007, and the 40 per cent in 2006.

But the warning signs are already apparent.

In case anyone missed it, Pandora, an ad-supported music service, turned off its UK service in January. Pandora complained that it could not generate enough revenue to pay for the music. Lime Wire seems to have come up with an ingenious advertising scheme, which involves selling contextual search advertising to the very people whose rights are being infringed as a result of those queries.

In an ad-supported world, the people who pay indirectly for your music are buying the scraps of attention an intermediary can sell them when you search for or listen to Death Cab For Cutie, for instance. Even the mighty Google hasn't managed to monetise that phrase in its general search offering, Adsense, and in its music channel shows an unconvincing Amazon ad offering 'Low prices on death for cutie.' Notice the circularity?

QTrax offers free, ad-supported music downloads

But even if you could break out and get music fans paying attention to financial services or cars, at current rates anything between 500 and 1000 impressions (streams or downloads) would be needed to return the same revenue as one paid-for track.

But with record companies making strategic investments in a new crop of on-demand music websites none of which has a working revenue model, brace yourselves for the next big flop. ®

Paul Sanders is a founder of Playlouder MSP, the world's first ISP licensed for music file-sharing. He is also a founder of the state51 conspiracy, an independent digital music distributor, and founder and director of strategy at Consolidated Independent, a digital media technical service provider.