Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2008/04/10/intel_otellini_interview_atom/

Can the Atom help Intel's CEO meet otherworldly demands?

Otellini bullish on MIDs, bearish on Affymetrics

Posted in Channel, 10th April 2008 23:22 GMT

Interview Exclusive Strolling towards Intel's headquarters, I hoped my meeting with Paul Otellini would not be as awkward as the last encounter with an acting Intel CEO.

Back in 2001, Craig Barrett delivered a keynote speech at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, which required him to emerge from a huge tub of Jello. Intel had hired its Blue Man Group chums to perform a brief show before the speech started, and they closed by revealing a massive Jello mold sitting atop a black box on stage. Then, they ripped into the Jello to reveal the head of Barrett. The executive proceeded to tear the rest of the way through the Jello, unfurl his body from the box and get on with his own show.

"The only way they got me in the box was that they told me the last living human being in the United States who wanted to buy a PC was in that box," Barrett said at the time. "I got in there and found out I was the only person."

I'm still not sure what that means, although it seemed to have something to do with the dot-com bubble bursting.

Anyway, I had ducked out of the keynote speech early since a colleague had been tasked with writing up the "event." Like any hungry, free-loading hack, I scampered away from the theater and right into Intel's secret VIP room, which had a lovely spread. I started digging into dinner, figuring no one from the company would be the wiser.

About 20 minutes passed, and the next thing I know, Barrett and his bodyguard bound into the room. Barrett still had Jello particles on his forehead, was sweaty and looking for a respite. He seemed puzzled to see me, which is understandable since this was meant to be an executives-only type of room, and I had pasta sauce dripping down my chin. Breaking the ice, I introduced myself and said, "I guess you want some alone time to relax?".

"Yeah," he said. The bodyguard directed me to the door.

The Paul Principle

The point of this story is that Barrett could get away with Jello. Like all the previous Intel CEOs, he worked off a rich engineering background, which is thought of as crucial at the company. Engineers can have blue goop falling off their face and still be taken seriously.

"We'd even question God's credentials if he became CEO," one Intel employee told me last week, emphasizing the point that Intel's culture revolves around engineering street lab cred.

Otellini (L) and Barrett (R)

The press loves to point out that Otellini is Intel's first non-engineer CEO. He's a sales and marketing guy. Such creatures struggle to command the same level of respect at Intel - even if they abstain from Jello molds.

But the very same employee who told me that God would need to demonstrate the ability to stretch beyond his non-engineering inadequacies, said that Otellini has won over the troops. Having been trounced for two years by a resurgent AMD, Intel's best and brightest confessed to needing a kick where it counts. Otellini delivered that kick through a "painful" set of layoffs and also through a set of "decisive actions" around off-loading lagging businesses, I was told. Beyond the cutting, Otellini infused the remaining Intel employees with a sense of urgency.

This sounded like the type of polished line that a press-trained Intel employee is instructed to hand out when he finds himself trapped next to a reporter on a 10-hour flight. And maybe it was the recycled air gnawing at my brain, but I believed this employee. Or at least, I believed that he believed himself.

Just how deep Otellini's acceptance runs would seem to matter little given recent results. The company has fixed the chip delays and cancellations that plagued it just a couple of years ago and has established an obvious performance lead over a bumbling AMD. Beyond these core businesses, Intel once again looks to expand into new markets through its Atom line of processors that slot into lower-cost computers, PDAs and eventually cell phones. In addition, Otellini has pledged to deal with Intel's memory woes one way or another to make sure they are not "a drag" on the company.

The folks who follow the chip game appear in consensus that Intel has seized a massive momentum edge over its rivals and appears poised to give these new business a real run.

We probed Otellini on a number of these topics and also his thoughts on Intel's future as a nanotechnology firm and the health of the semiconductor industry moving forward as fab costs continue to rise and rise and rise.

Atom and Peeve

During a recent investors conference held at Intel's headquarters, Otellini talked up Intel's growth strategy, saying the company hoped to capitalize on new classes of systems. Some of these systems resemble the ultra-mobile PCs that haven't been terribly popular - but Intel's versions of the kit are cheaper and often lower-end products. The idea is that rich computer-savvy types will buy these systems as lightweight, near-disposable e-mail and web checkers, while the less fortunate will purchase them as their primary computers. In addition, Intel is looking to expand through beefier mobile devices likes smartphones, via more consumer electronics devices like set-top-boxes and through more embedded systems by placing lots of processors in cars and refrigerators.

The Atom processor and its future derivatives will play a crucial role in these efforts, as Intel tries to ship a powerful but low-energy part into these new markets. During the investor conference, Intel, in my mind, received quite a bit of push back from the financial types who have seen Intel try and fail to crack fresh areas in the past. The company, for example, has sold off an older, unsuccessful low-power chip business. A number of people present at the conference hit us with skeptical comments around Intel's rosy picture of the future, and one analyst, during the gig, even suggested that Intel give up on growth and stick to making the most out of its dominance in existing markets.

"I guess that I don't agree with your characterization," Otellini said.

"It's all relative, right? I talked about this for the first time a year ago at the analyst meeting. I talked about the three new big markets we are going after with the Intel Architecture. This year, I expanded it to four. I added the embedded stuff.

"A year ago, there was no silicon product. There were no end products, and there were no design wins. A year later, all three of those are different. So, my view is that a year ago the range of view from my perspective was from 'no way' to 'hmm, interesting.' And this year, it is from 'hmm, interesting' to 'there may be something here.' Maybe a year from now, it will go from 'there's something here' to 'wow.'"

The most surprising positive reaction to the new push, according to Otellini, came from the analysts' appreciation of so-called NetBooks - the lower-end laptops.

"Netbooks is a category that we invented less than a year ago and talked about publicly for the first time less than six months ago. And now it has become a category that is the hottest thing on the market today."

One need only look at all the buzz around the Asus EEE PC to find at least some evidence supporting Otellini's claims.

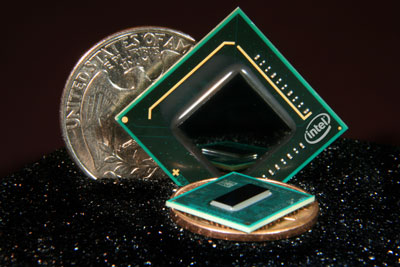

Intel's Atom chip on top of giant US currency

As Otellini sees it, the Netbook success bodes well for ventures in the PDA and smartphone markets. Sure, Intel has tried this before with the StrongARM/XScale products, but this time around "there's a better value proposition," as Intel relies on its own, familiar architecture rather than an ARM design.

"We knew where we were going awhile back, and being one of a thousand licensees to ARM doesn't seem to be the way to solve the problem of getting the internet into your pocket.

"The instruction set, to me, is a much better value proposition because we are bringing the entirety of the internet to these devices and adding voice. The alternative is that you have voice and then try to bring the internet to those machines, and the internet is not programmed around ARM. The internet is all javascript. It is all Adobe Air. It is all Flash. That's our heartland."

It must be noted that ARM advocates reject Intel's claims of a performance and ease-of-development edge. They argue that Intel is charging after a go-it-alone strategy in a mobile market that thrives on partnerships and the ability to tweak processor designs to meet specific needs. And, if you're looking for a standard, the argument goes, ARM is already that standard. Intel is simply adding confusion and more software effort to mobile application development.

With any luck, consumers will end up as the beneficiaries of this architecture war as more complete, functional mobile devices come to market, replacing the over-hyped, under-powered gear today.

Jumping past Intel's near-term agenda and well into the future, I wondered how the company might apply its nanotechnology expertise to areas outside of the traditional semiconductor field. Companies such as Applied Materials have re-tooled semiconductor manufacturing equipment to pump out silicon-based solar cells, and a number of start-ups have issued specialized processors that can crank through tasks such as protein folding at remarkable speeds. Perhaps Intel would like to have a go at something along these lines.

"We have looked at both of those markets," Otellini said.

"There is no commonality between our factories and the factories that you would need to run to build solar cells. The equipment is different, the factory flow is different, the clean-room levels are much less necessary. And, for solar factories, you need these big, long almost football field kinds of buildings with a linear process control. So, there is not a lot of re-use of, say, our old factories or old equipment.

"So, you would have to enter it as a standalone business, and that doesn't seem to be attractive to us right now in terms of where our capital can be used.

"It's a similar story on stuff like the Affymetrics products. As we investigated the various aspects around digital health, we looked at those kinds of things. We're really good at digital logic, and I think that is where we want to keep our focus."

So, if we're to think about Intel as a nanotechnology company, we should stick close to how the nano concepts relate to semiconductors and not much beyond that?

"Well, we have deep research in terms of what happens at these ultra-small dimensions, and we are working with carbon nanotubes and those kinds of things. But that is all multiple generations out.

"We've got a line of sight for four more generations of silicon scaling. That's eight or nine more years. That is about as far out as we have things that are typically moving towards production."

I thought Otellini might bite a bit more on these nanotechnology questions. The company loves to deal in high volumes and Affymetrics gear obviously does not offer such volume opportunities yet, but the solar cells at least have moved in the mass production direction.

But no such luck.

The executive, however, did prove more than willing to dig into the state of semiconductor manufacturing as the industry navigates through 45nm and onto 32nm.

The immense costs associated with building semiconductor plants continues to take a toll on some of the technology industry's biggest names. Texas Instruments, where Jack Kilby invented the integrated circuit (hats off to Noyce as well), has opted to bail out on the 32nm endeavor. Meanwhile, the Japanese giants form as many partnerships as possible around sharing research and production costs, and IBM tries to bring on as many customers/partners as it can. The fabrication set in Taiwan face similar cost issues and must keep their factories full while staying on top of the latest and greatest processes.

In many ways, this pushes Intel more and more toward a world where it's the only vendor able to compete as an independent.

"Samsung, TSMC and Intel are certainly maintaining the integrated production model, although TSMC's output is really obviously foundry driven," Otellini said. "They are not finding the need to partner to develop future technology or to share capacity."

[We believe Samsung does in fact have a 32nm deal in place with IBM and Chartered - Ed]

"This is just economics. If you are going to build to a world-class scale, in order to recoup that $4bn-$5bn investment at reasonable margins, one needs to have revenue in the range of $5bn-$6bn a year coming out of that factory. There aren't many semiconductor companies with revenue greater than $5bn-$6bn."

"From our perspective, those types of sharing arrangements are sub-optimal. We like to optimize product and process technology for each other."

Otellini points to notebook chips as one area where Intel wanted to feed a growing market with as many chips as possible and was forced to confront power issues head-on in order to deliver competitive products. This pushed Intel to jump to a new substrate - Hafnium - earlier than it might have expected. As a result, the company's entire processor line benefited.

One could argue that competitors such as Transmeta also pushed Intel in the low-power direction and that such rivals seem less likely to appear moving forward due to the costs of playing in the semiconductor game. The foundry model does present start-ups with a nice option for reaching production scale without investing in fabs. But we've seen companies such as Transmeta, PA Semi and even the yet to de-stealth Montalvo Systems struggle to compete against Intel's - and to a lesser degree AMD's - stranglehold on the x86 laptop, PC and server chip markets. These start-ups can conjure up technical edges over Intel, but such gains seem near impossible to achieve and short-lived when they do occur. Doesn't a lack of competition threaten to make Intel complacent in these mainstream markets and also to raise more potential anti-trust issues for the company?

Intel VP Pat Gelsinger discusses his engineer superpowers

"There is nothing against the law about being better than another company," Otellini said. "In fact, that is the nature of technology.

"I have done this for over three decades. Technical leads are transient. You can be disrupted by your own new products. You can be disrupted by somebody else's new products.

"I don't have sleepless nights worrying about lack of competition. Like I said, I have been doing this for three decades, and there has always been someone nipping at our heels."

From Jello to DARPA

I closed out the conversation with Otellini by looking at one area where Intel faces plenty of innovative competition - supercomputing.

The Defense Department tends to fund some of the most interesting machines going, and Intel has failed to win or even be part of many of the large, recent handouts. IBM and Cray, for example, split a massive award around large-scale systems and will rely on Power and a mix of Opterons and accelerators, respectively. In addition, the biggest machines coming up this year in the US will run on Opteron chips.

Otellini, however, said that Intel does in fact have something in store with DARPA.

"Watch this space," he told us.

But what exactly is Intel's relationship like with DARPA?

"We have participated in those kinds of deals in the past. In the old days, we actually built a supercomputer and sold one to Sandia. But nowadays those contracts tend to be best fulfilled through OEMs. So, they are still interesting to us and watch that space."

But I haven't seen a large contract announ. . . .

"I am not going to go there."

Ah, well, I tried.

Sun, IBM, HP, Dell? Bueller? Bueller? Bueller? Go on, boys, you know where to send the e-mail.

And with that, our Otellini moment came to an end. The marketing guy. The sales guy. The guy expected to meet deity-level standards said goodbye and dashed out of the conference room.

"How do you like that," I thought. Last time I'd been in that office, no less than Gordon Moore took me a on personal tour of his double-wide cubicle and then walked me out of the Robert Noyce Building. This time around, I was escorted off the premises by a Greek henchman.

But, you know, those engineering types have a bit more polish than the marketing guys. ®