Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2008/04/02/dab_disaster_analysis/

Fixing the UK's DAB disaster

Beyond the bubbling mud

Posted in Legal, 2nd April 2008 09:44 GMT

Analysis How does the UK find its way out of the DAB disaster? First, we have to get beyond the denial stage and into acceptance.

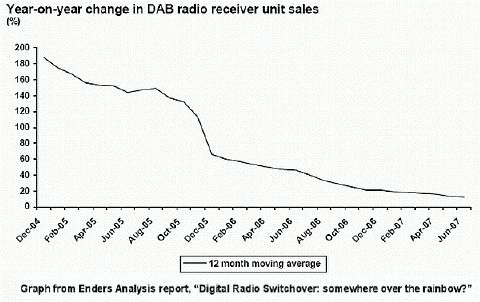

One thing is certain: the UK can't carry on the way it's been going. Digital radio's year-on-year sales growth fell off a cliff the moment the BBC stopped its "DABaganda" TV ad campaign in the run-up to Christmas 2005, and sales growth has continued to slide ever since. That's despite every receiver being pseudo-subsidised by the BBC's TV adverts to the tune of £25. The Beeb has run 19 such campaigns.

DAB's spectacular sales growth.

The sales chart shows DAB is a failing format, and if it were subject to the market, it would be on its way to the format graveyard. Successful formats don't need free adverts on BBC TV to prop them up.

A DABload of fail

Since the DAB system consists of technologies that date back to the 1980s, the ideal solution would be to switch it off and start all over again. Unfortunately, there are already 6.5 million DAB receivers in the market, so that might lead to a few complaints.

One of the things the broadcasters have been doing wrong, ironically, is that in trying to push everyone towards DAB they've actually been holding back the number of people who would choose to listen digitally. Eighty-seven per cent of all households now have digital TV and 60 per cent of households have broadband, both of which carry digital radio. So the BBC should logically promote all of the digital radio platforms on an equal footing, giving consumers the choice of which platform they want to listen on, without the BBC deciding for them.

Listening to the BBC's internet radio streams jumped 22 per cent in one month on the back of the launch of the streaming iPlayer. That's six times faster than the rate at which DAB radio set sales are increasing, and the internet radio streams weren't even being directly advertised. This shows that concentrating solely on DAB is holding back digital radio take-up as a whole.

The BBC also admitted last year that DAB had become "prohibitively expensive" to roll out to everyone (DAB works out as being four times more expensive than FM (BBC pdf) to provide universal coverage), and coverage isn't even universal.

We now know that only 90 per cent of the population will ever receive the BBC's stations on DAB. So the BBC shouldn't be promoting DAB as if it's the one and only way to receive digital radio - because six million people in the UK will never receive it.

Bubbling mudbath

DAB's main problem from a listener's standpoint is simply that it provides poor audio quality. Far too many people suffer from poor reception quality: people hear the dreaded "bubbling mud" if they're receiving a weak DAB signal. The choice of stations is also poor. The solution is to switch to using DAB+ instead.

DAB+ is really just the old DAB system but with the AAC+ audio codec and Reed-Solomon (RS) error correction coding added "on top". AAC+ is three times as efficient as the MP2 codec DAB uses, which means DAB+ can provide much higher audio quality and carry more stations. The stronger error correction coding makes reception quality far more robust, too: the bubbling mud would disappear for virtually everyone if stations switched to using DAB+.

The sad thing is that AAC (without the ë+í) and RS coding were both available from 1997 onwards - five years before the BBC relaunched DAB in 2002. The current fiasco was entirely avoidable.

One of the main reasons why GCap Media chief executive Fru Hazlitt labelled DAB as being "not an economically viable platform" was due to its high transmission costs. DAB+ is up to three times cheaper to transmit, because multiplexes can carry three times as many stations. The cost of conversion to DAB+ would be minimal as well, because DAB+ stations would be transmitted on existing DAB multiplexes, so there's no need to build an expensive new transmitter network.

A licence to deceive

Despite DAB+ solving DAB's numerous problems, Ofcom has scuppered any hopes of seeing it anytime soon. Channel 4 has made a serious investment in digital radio, and wanted to use DAB+ for stations on its national DAB multiplex, due to launch later this year. But light-touch regulator Ofcom wouldn't let them, and Channel 4 was ordered to use DAB instead.

However, which format is used on the Channel 4 national multiplex may have become a moot point, as it might not be launching at all - most of the broadcaster's executives are reportedly opposed to the £100m move into digital radio. Executives are aware that splurging on digital radio would make a mockery of the broadcaster's request to receive a share of the BBC's TV licence fee money, on the basis that they're supposedly skint.

What Ofcom is scared of is that if DAB+ stations were launched today there would be complaints from a few luddites who think technology should stand still forever. But the introduction of DAB+ would not lead to them losing any existing stations, or at least not for some time, and the irony is that DAB stations have been closing down left, right, and centre anyway.

Ofcom should simply have explained to consumers that their DAB radios won't stop working the moment DAB+ stations launch. A green light for DAB+ would also have forced the receiver manufacturers to convert their existing models to support DAB+, and that would have accelerated the transition over to the new standard.

But what Ofcom has actually achieved is giving an excuse for the receiver manufacturers to delay building new DAB+ models. The broadcasters have been misleading the public into thinking that DAB+ will never be used in the UK, so we continue buying non-upgradeable DAB radios that will all need to be replaced a few years down the line. No one seems to be able to grasp the nettle.

Future proofing the radio

There are a few DAB+ models on sale today, and the manufacturers will be releasing a wide range of receivers later this year in time for new markets in Australia, Switzerland, and Germany, who are all starting to use the new standard. But it's unlikely that there will be any DAB+ stations launched in the UK before 2010 to 2011, and even then it will take a few years to complete the transition. By which time DAB+ will be as outdated as DAB is today.

If the broadcasters want DAB to continue being the main digital radio platform, they could live to regret taking the slow route to DAB+, because listening to internet radio is set to grow quickly on the back of the iPlayer.

The BBC has finally said it's going to start using new audio formats - very likely AAC or AAC+ - for its live and on-demand radio streams in July and April, respectively. This means they should overtake DAB in terms of quality. The BBC has actually had the opportunity to use AAC+ for its radio streams ever since Real Networks added support for the codec to Real Player 10/RealAudio 10 in January 2004, and it wouldn't have cost the BBC a penny in licensing costs to use it.

Which begs the question: has the BBC actually delayed using AAC+ in order to give the failing DAB system a helping hand? We can but speculate, but it's a concern that the BBC's "all platforms" strategy and supposedly web-friendly mission has a blind spot when it comes to internet radio.

The lure of multicast

The BBC is also due to launch multicast (one-to-many IP streaming) this year. This promises to deliver stations from the BBC and a number of commercial rivals at higher quality than DAB+ is ever likely to.

Multicast is a key technology for delivering live TV channels on IPTV platforms, as it's so bandwidth-efficient. But it's received little support from ISPs up to now, because ISPs are still being heavily reliant on BT's network, and BT's current network doesn't support multicast.

BT has recently demonstrated delivering video using multicast over its shiny new 21CN next generation network to assembled journalists though, and Sam Crawford, who's behind the Samknows Broadband website, said he'd be massively surprised if [BT] didn't release [multicast] or at least announce it this year".

So with five of the six biggest ISPs either looking to provide, or already providing, IPTV it would be surprising if multicast wasn't widely available to broadband users once BT has rolled 21CN out nationally. That's due to happen by 2010.

A quarter of broadband users will be getting multicast support later this year when Virgin Media launches its 50 Mbps cable broadband package, which will include an HDTV channel called VoomHD that will only be available via multicast.

A technology tragedy

The BBC's radio programmes are also due to be incorporated into the P2P download version of the iPlayer, which should make them available at better-than-DAB+ quality and, if the BBC does invest in a content delivery network (CDN) for the iPlayer TV streams, that would potentially allow the quality of both the TV and radio on-demand streams to be improved because the CDN should significantly ease the bandwidth burden for the ISPs.

The mobile broadband platform is also looking promising, with plenty of investment in high speed data infrastructure. In theory, 3.9G and 4G that are due to be deployed between 2010 and 2015 will offer peak download speeds ranging from 100 Mbit/s up to a few Gbit/s. So if the BBC would allow mobile users to download on-demand files, rather than making people use their slow P2P network, these files could be downloaded very quickly.

These future technologies will have their own version of MBMS (Multimedia Broadcast Multicast Service), the broadcast standard in 3G. So considering that NTT DoCoMo's 4G candidate system is theoretically 223 times more spectrum-efficient at carrying digital radio than DAB and 79 times more efficient than DAB+, any such 4G broadcast standard would inevitably make DAB+ look ridiculously inefficient in comparison. And this in turn would raise serious doubts over the economic viability of DAB+. Ofcom's decision to delay using DAB+ will be seen in years to come as a mark of technology tragedy.

Ofcom's £270,000 per year CEO Ed Richards is said to be concerned about his legacy. Crippling the nation's radio is a sad one to leave us with. ®