This article is more than 1 year old

Google accused of hard-coding own links in search

Harvard prof waves Google antitrust 'smoking gun'

Updated Update: This story has been updated with comment from Google.

In a still-simmering Google antitrust complaint, UK-based vertical search outfit Foundem accuses the Mountain View web giant of using its search monopoly to unfairly favor its own services over those of its competitors. Google chief executive Eric Schmidt denies the accusation, arguing that the company's search engine always delivers "the best end-user outcome." But Harvard professor and noted Google watcher Ben Edelman believes otherwise.

He says he's found a "smoking gun" that indicates Google's search engine does in fact favor the company's own services.

Edelman says his evidence shows that Google may "hard-code" its own links to appear at the top of certain algorithmic search result pages, including links for Google Finance, Google Health, and other Mountain View-operated web services. In other words, these links appear independently of Google's search algorithms, undermining the company's off-stated claims that its search results are unbiased and completely automated.

"Google's use of hard-coding and other search bias gives Google an important advantage in any sector that requires or benefits from substantial algorithmic search traffic," Edelman writes in a blog post unveiled on Monday morning. "By directing users to Google services, Google can make its offerings take off in a broad class of services — be it health, finance, maps, video, travel, or otherwise.

"Meanwhile, entrepreneurs recognize and anticipate that Google may bury their results as it favors its own services — blunting the incentive to build a business that competes with Google or competes with a service Google might plausibly develop. With Google already putting its Health and Finance sites first, even when user consensus is that other sites are preferable in these categories, it's easy to envision a future where user preferences and genuine excellence are less important than Google's rote power."

The implications are potentially far-reaching. "This could be very important in the long run," Edelman tells The Register. "In the long run, when Google is sued in comprehensive antitrust litigation and we get to see the processes that yield the [search results], this will be one of the smoking guns that guides the discovery."

Asked to comment, a Google spokesman provided the following statement: "We built Google for users, not websites, and while think it’s important to be transparent with websites about how we rank sites, ultimately our goal is to give users the most useful answer possible. Sometimes the most useful answer is a list of links, but other times it's a stock quote, a list of movie times, or quick answer to a question. That's what users want."

He also said that Ben Edelman has been a paid consultant for Microsoft.

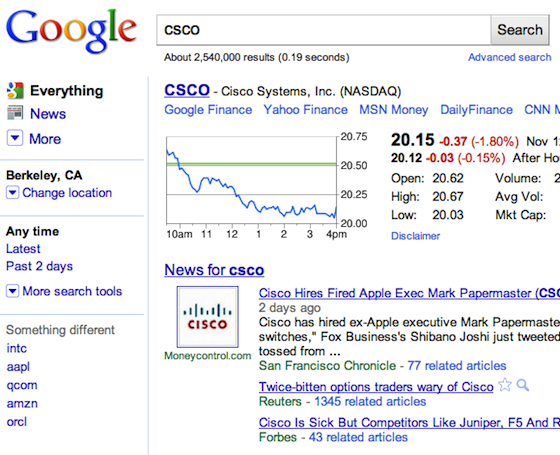

Edelman begins his argument with a standard Google search for "CSCO" — Cisco's stock ticker symbol. Google returns a Google Finance page as the top result — though it's not labeled as such — and the next two most prominent links (a stock price chart and a link that does say "Google Finance") point to the same Google Finance page. This despite the fact that according to comScore, Google Finance is not the web's most popular finance site. You can see the search here (Google's "Instant" search is turned off, but the same behavior can be reproduced when it's turned on):

The question, Edelman says, is whether or not Google algorithms select Google Finance for these top spots. "How do Google's less popular services come to receive such valuable placements? Does favorable pagerank (or other favorable reputation) of google.com spill over onto other Google services to guarantee top position under standard ranking algorithms? Or have Google staff manually adjusted ('hard-coded') search results to give favored treatment to other Google services?" he asks.

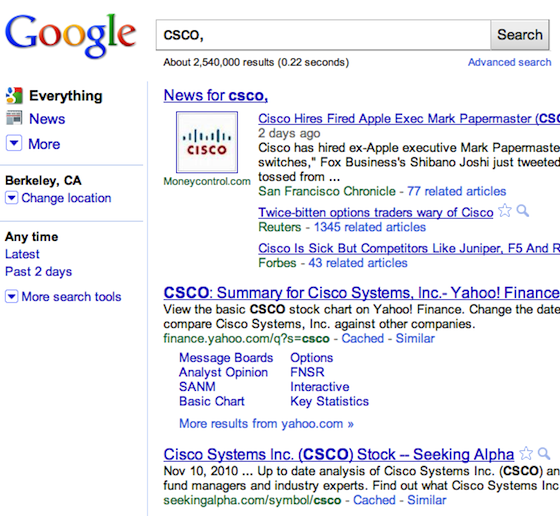

Yes, Edelman argues they're hard-coded. To buttress this claim, he performs the same "CSCO" search, but with a comma at the end. With the typical algorithmic search, adding a comma doesn't affect the results (Edelman offers a "comma search tool" to show this). But if you search on "CSCO," — rather than "CSCO" — those Google Finance links vanish:

"What system design could explain that disappearance?" Edelman says. "My best assessment: If Google staff manually specified that a given result should appear at the top of results when users search for a specific search term, they might well forget to include search term variants with appended commas. Then a user searching for an unexpected variant, including by adding a comma, can see 'true' Google algorithmic search, unaffected by the manual overrides."

Edelman points out similar behavior with searches involving health terms. If you search on "acne", the three most prominent results are for Google Health. But these disappear if you add a comma — or make other small changes. And the same goes for every term listed in Google's Health Topics index. "While exact searches for the listed terms yield prominent links to Google Health, any tiny variant causes the Google Health results to disappear completely," he says.

He also lays out several other similar examples, spanning everything from travel deals to movie listings to patent filings.