This article is more than 1 year old

Boeing big cheese repeats pledge of 737 Max software updates following fatal crashes

Airline maker accused of not realising what controversial MCAS system could do

Boeing chief exec Dennis Muilenberg has repeated earlier promises that a software update for the troubled Boeing 737 Max airliners is coming "soon".

In an open letter published last night Muilenberg acknowledged the "shared grief for all those in mourning" after the separate crashes of two 737 Max 8s within a few months - Ethiopian Airlines flight 302 and Lion Air flight 610. The crashes killed a total of 346 passengers and crew.

Much attention has been paid to a new software feature of the 737 Max series aircraft, the Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS. This adds nose-down trim input to the airliner when it senses that the jet is nearing a stall.*

"We're united with our airline customers, international regulators and government authorities in our efforts to support the most recent investigation, understand the facts of what happened and help prevent future tragedies," wrote Muilenberg. It was not until China grounded all 737 Maxes in its airspace, followed by the rest of the world's aviation regulators, that US authorities eventually acted as well.

Muilenberg continued: "Soon we'll release a software update and related pilot training for the 737 MAX that will address concerns discovered in the aftermath of the Lion Air Flight 610 accident."

That promise of a patch was originally made a week ago. Various news outlets reported that it would be deployed by the end of this month, rather than April as was originally expected before the worldwide grounding.

The Seattle Times, which covers the local area around Boeing HQ, reported that an internal Boeing safety analysis of MCAS "understated the power of the new flight control system" and failed to spot that "MCAS was capable of moving the tail more than four times farther than was stated in the initial safety analysis".

It also reported that Boeing's analysis "failed to account for how the system could reset itself each time a pilot responded, thereby missing the potential impact of the system repeatedly pushing the airplane's nose downward".

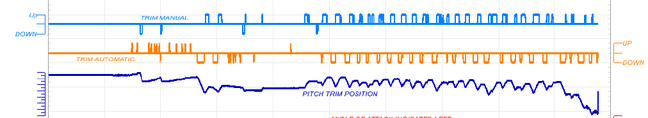

The Indonesian authorities' initial analysis (PDF, 12.7MB, 78 pages) of the flight data recorder (black box) from Lion Air 610 showed the pilots repeatedly undoing trim settings made by MCAS, only for the software system to repeat its input.

An extract from Figure 5 of the KNKT preliminary report into the fatal crash of Lion Air flight 610. The yellow graph shows MCAS inputting nose down trim with the light blue graph showing the pilots countering it with nose up trim. The dark blue line shows the ultimate position of the trimmer ending at almost full nose down. Click to enlarge

Unlike the other automatic trim systems aboard Boeing 737s, MCAS was written to operate in 10-second bursts. The system reportedly takes its critical inputs, from which it decides whether the aircraft is near to stalling and therefore needs nose-down trim, from a single angle-of-attack sensor at a time.

Boeing described the Seattle Times' reporting in a statement to that newspaper as containing "significant mischaracterisations" and saying it could not comment further because of the ongoing investigations into the crashes. ®

*Stallnotes

An aircraft is said to stall when its wings are no longer generating enough lift to keep it flying. This normally happens because of low speed and a nose-high attitude (the aeroplane is being pointed upwards). When the aircraft stalls, its wings are no longer producing enough lift to keep it in the air so it starts descending. When an aircraft stalls close to the ground, the odds of recovering it back into controlled flight are greatly reduced.

Trim is basically balancing an aircraft. When it's correctly trimmed, an aeroplane will fly straight and level without the pilot needing to constantly hold the controls and keep it there. MCAS was intended to add nose-down trim if it thought the aircraft was getting close to stalling. It's a bit like having a second pair of hands on the controls, pushing the aeroplane's nose down to help pilots avoid a dangerous stall.

One way of thinking about the original 737s, the 737 Max design and the Max's need for MCAS is to imagine a boring family car like your dad used to drive. Take that car, replace its engine with a V12 and put monster truck wheels on it. If you tried to drive it in the same way as you used to before the upgrades, you'd find the handling very different. But if you had a magical software box between you, the engine and the steering, you could program it so the car would feel the same to drive as it did with the original engine and wheels.

This is broadly what Boeing did when it put much larger engines on the 737 Max: it tried to compensate for the handling changes with software. Some pilots have alleged that original training courses on the 737 Max glossed over what MCAS was and how it worked.