This article is more than 1 year old

Why Uber isn't the poster child for capitalism you wanted

So it can drive rivals out of business, but what do they offer that's different?

Comment Within minutes of Uber losing its licence to operate in London, Uber became a totemic icon of innovation and free enterprise market capitalism that was being crushed by vested interests in cahoots with bureaucrats. Boo to the corrupt, killjoy socialists! Hurrah for innovation! Sign the petition!

But this is a simplistic, cartoon picture of the world. As an icon of free market innovation, the wrinkles begin to appear very quickly. Even free-marketers can comfortably take exception to it.

The issue isn't whether Uber is "disruptive", but whether it's engaging in a fair fight, and whether a fair fight is even possible. Because Uber is effectively bringing two big guns to a knife fight.

The Institute of Economic Affairs sees it in very simple terms:

Uber = competition (good). TfL = protection (bad).

One is cash. The many billions in VC capital Uber has acquired that allow it to engage in predatory pricing. Uber is losing money on every journey: we just don't know how much. The other weapon is euphemistically called "labour market flexibility". As I wrote here over three years ago, it's de-risking itself by putting the risk on the drivers and passengers. You can do this in London, a city where the real population may exceed official estimates by a million.

Alan Patrick of Broadsight calls Uber a "labour arbitrage" play. I haven't found a better description.

It's the long-term economics of Uber's model that we need to look at. Thankfully people already have, and with perfect timing there was another last week.

In 2016, transport expert Hubert Horan wrote a 10-part series of articles about Uber for Naked Capitalism. He distilled it into a draft paper, Will The Growth of Uber Increase Economic Welfare?, destined for Transportation Law Journal, but you can download it for free here.

Horan takes a very long-term view. He has little time for the hyperventilating technology and business journalists, overnight experts who regard Uber's ultimate victory as inevitable. It isn't, he points out, because the fundamentals of urban transportation haven't changed.

In many cases, such as telecoms, deregulation was introduced with great success. Few would now argue that having just one mobile phone operator per country would be a good idea. But this is different.

But what everyone forgets is that on-demand urban transport is still a dull old business. There are a few profitable routes, and lots of loss-making ones. Capacity doesn't miraculously expand in response to demand via price signals, and efficiency doesn't increase in response to competition, or at least not very much.

Uber, too, could go under some day

"No one has been able to explain why an industry that has been competitively fragmented and structurally stable for a hundred years should suddenly consolidate into a global monopoly," Horan notes.

"No one can demonstrate a clear link between specific Uber product features and its meteoric growth, explain why no one else had ever recognized these opportunities, or document how they are powerful enough to allow Uber to rapidly drive all incumbent taxi and limo companies out of business. No one has conducted an independent investigation of whether an unregulated dominant Uber would actually produce long-term improvements in the quality of urban transport."

Why is Horan so confident that Uber will fail? He notes that thousands of articles written about Uber were largely emotive and ideological, and assumed Uber had some magic network and scale advantages, or technological advantages, like an eBay or Amazon.

In a nutshell, it will fail because it's unlikely to provide a service at a significantly lower cost than rivals, and unlikely to be able to lock down competitive advantages.

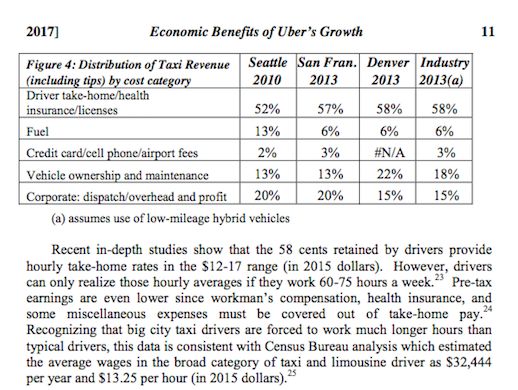

Uber has stubborn overheads to cut.

Source: Horan

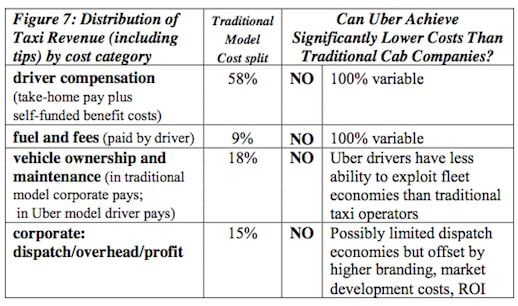

Uber lacks the scale/network economies needed to rapidly achieve profitability in a competitive market. Uber is a substantially less efficient producer of urban car services and has no significant sources of competitive advantage over the traditional operators it has been driving out of business.

Far from what Uber's supporters fervently believe, Uber is "much less efficient [and] has higher costs than traditional car service operators in every category, except for fuel and fees, where no operator can achieve a cost advantage".

How so? It takes twice the proportion (30 cents in the dollar) in overheads as a commercial rival (15 cents in the dollar). Local cab companies don't need to advertise or lobby on a global scale – which isn't cheap. Independent contract, Horan also argues, isn't actually an efficiency either. Drivers have no incentive to work better (just longer hours), and Uber won't fire lousy drivers – it doesn't employ them.

Horan doesn't defend the rent-seeking licensed taxi business (in the US licences are referred to as "medallions"); he argues that the consumer doesn't recapture the rent.

An Uber monopoly would control information about "demand, capacity and pricing, driver employment and compensation" making the task for new entrants difficult.

Other critics, most consistently the author Tom Slee (interview), have pointed out that Uber uses predatory pricing to drive commercial rivals out of business, while positioning itself to supersede city-funded transport infrastructure. It's ironic to think that the best hope for Uber, this weekend's poster child for enterprise, sees its future as a taxpayer-subsidised monopoly.

One strong supporter of free market capitalism isn't fooled.

"Uber wants to be a monopolist, too. It doesn't believe in fair competition, and it doesn't practise it, either," writes Dominic Lawson, making use of Horam's arguments.

Lawson's point won't be popular with London's largely middle-class users who have been getting their rides home subsidised by Silicon Valley VCs, and the Saudis. Some people just don't want to look the gift horse in the mouth.

Rather than being an icon of competition and innovation, Uber could be a lasting emblem of how Silicon Valley ran out of gas. ®