This article is more than 1 year old

Of mice and migrations: How a rodent's DNA maps to architectural complexity

Don't cloudify your IT infrastructure lightly

Managers of enterprise systems are being bombarded by messages touting the supposed benefits of cloud for cost reductions and greater IT “flexibility.”

Bosses are pressured to, for instance, develop a hybrid solution of off- and on-premises systems: the difficult stuff is left in the company’s private cloud, and the rest migrated to a public service.

But whether you move the whole or just part of your infrastructure to the cloud, it is essential you first get a grip on your IT estate. Failure to do so will mean you risk seriously underestimating the cost and the risks of a move, thereby undermining the supposed gains associated with going cloud.

Fundamental to the question of the cost of migration is: just how complex are the IT systems that support a modern enterprise? Are they sufficiently documented or well understood, such that an executable migration plan can be developed at all? Do safe islands exist within this ocean of complexity – islands that could be migrated to in a relatively straightforward way in order to go hybrid?

As you enter a data centre, if permitted, you will see neat rows of racks with well-wrapped bundles of labelled cables and a clean liftable floor. It is difficult to imagine a more ordered scene, but does this reflect reality?

No. The true complexity of the IT support is based on the interactions of the IT components (services) that support the business. These are not directly visible in the physical world – they are based on the network, or backplane, communications between the services.

Many vendors can, and do, sell measurement technology that can observe these network interactions taking place, but just how useful is this raw data at scale?

Having been presented with such survey data for many multi-nationals, in many businesses, representing more than 200 distinct data centres, I have faced this challenge more often than most.

An interesting starting point is to ask: just how complicated is the IT support for a modern, enterprise-scale organisation? This is an important point, because it will determine the difficulty a manager or developer will face in transforming any part of the IT system because it tends to interact with itself.

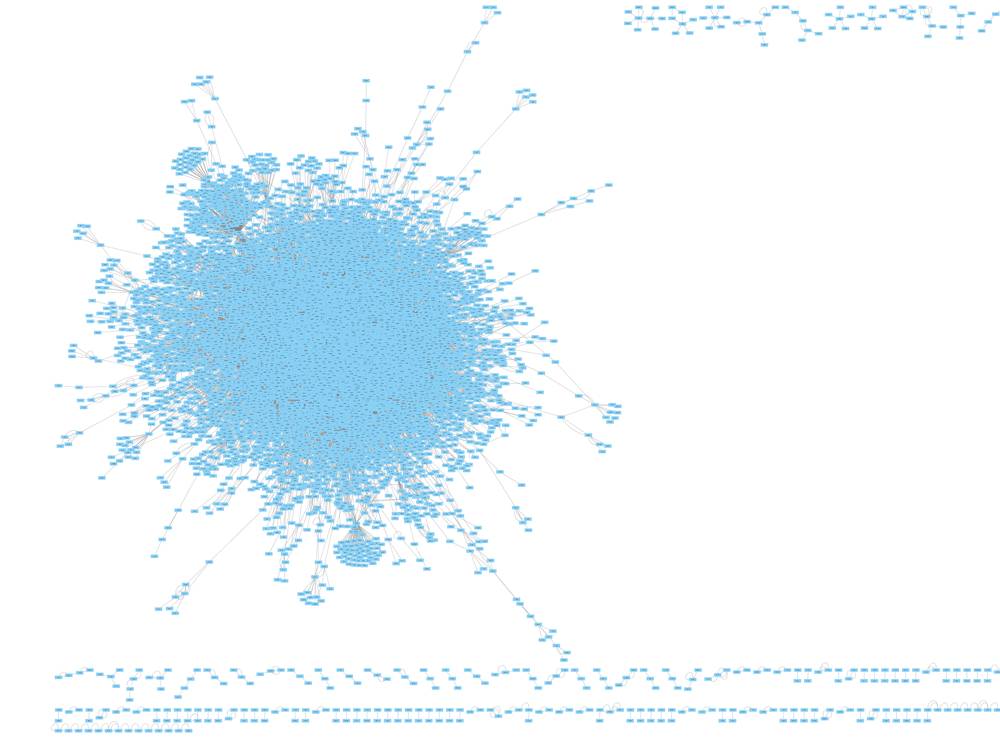

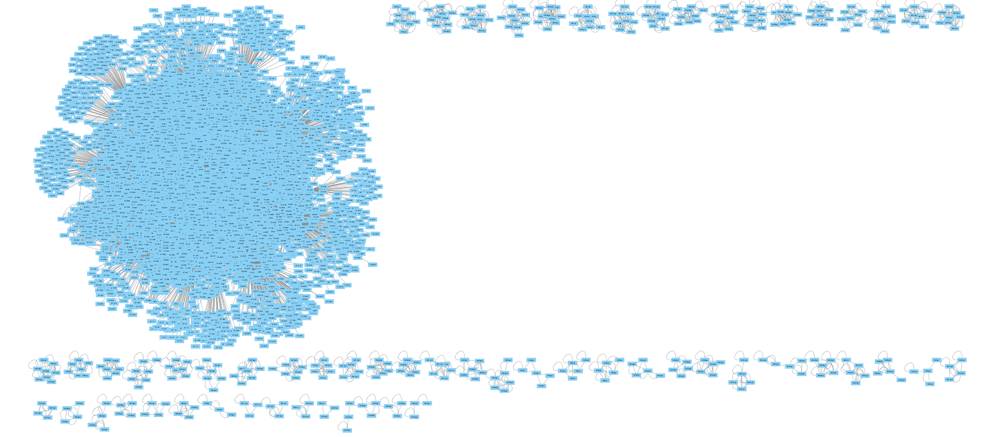

The picture above is of the mouse genome interaction map, while the picture below shows the IT support map for a medium-sized enterprise.

The mouse genome is obtained using Cytoscape (a free biological network modelling tool). Why is it here? Because it can be used as a point of reference for complexity – other genomes are available, but pretty mice are cute and are generally considered to be quite complicated.

The second map is of a genuine, medium-size enterprise and it is roughly one quarter the size of the largest enterprise IT system I’ve encountered. Given this degree of complexity, the question arises as to whether there are any changes to these systems that can be made without risk.

At this scale the result of our survey may well generate an aesthetically pleasing image, but how do we turn that into useful human-interpretable maps, which support transformation and maintenance activities in the data centre?

The simulated IT support system above is of medium scale for an enterprise, roughly one large data centre for a big multinational. It has roughly the same number of entities and interactions as the mouse genome (8,000 distinct nodes, and 2,000 interactions).

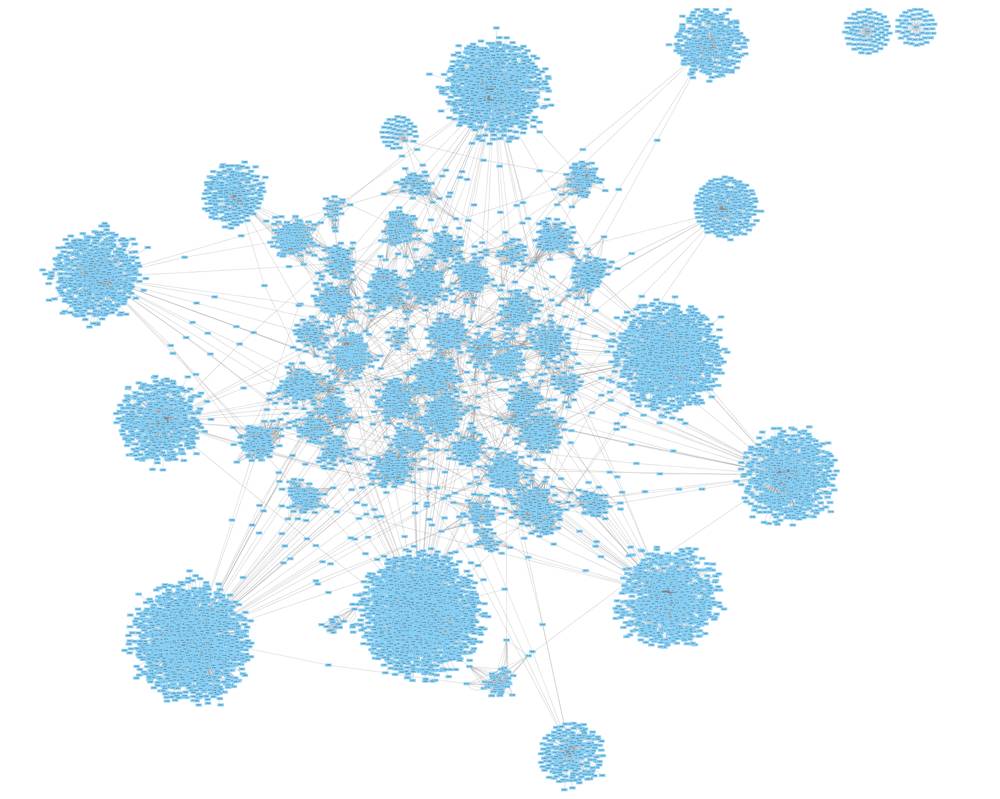

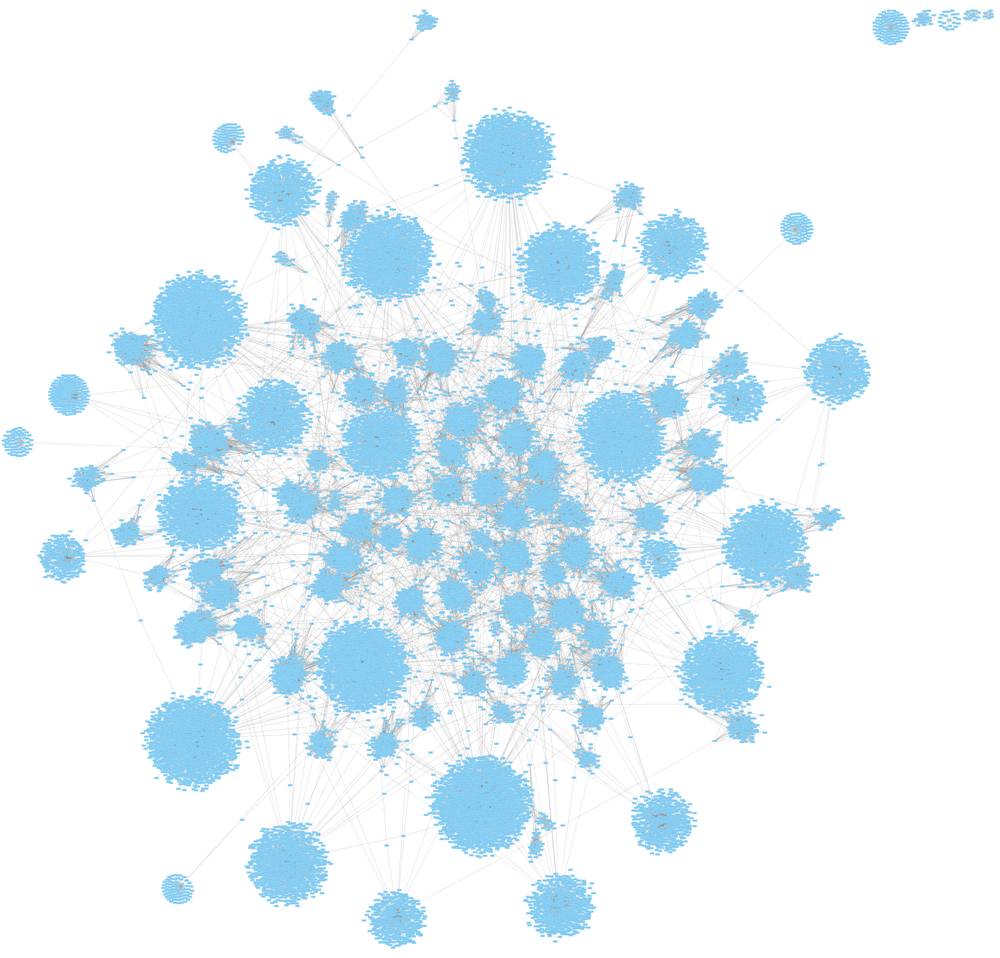

Remembering that the number of potential interactions goes roughly as the square of the number of distinct nodes, I’ve worked on making meaningful maps of IT systems ranging in scale from about 200 to 110,000 distinct IPs. In the interests of data centre art, I include what would be about half the scale of the largest mapping challenge faced – which would appear roughly like this:

Given the complexity of IT support for the modern enterprise, it is of little surprise that attempts to modify or transform these systems proceed neither rapidly nor cheaply, and often end in what can only – even sensitively – be described as failure.

The demand placed on IT is that we attempt to hack systems more complex than the genome of a mouse and do so blind, doing it randomly and with minimum expenditure.

The hope is you’ll obtain a hamster, but don’t be surprised if you get a rat that bits you in the apps. ®