This article is more than 1 year old

In this Facebook and Google-owned world, it's time to rethink privacy

New paper suggests ways to grab control of your data

And so what's the answer

Of course you've heard all this before and the well-worn paths go in two directions. First, just shut up and deal with it or stop using the service. Or second, learn how to work within the system: why did you drunkenly post that message anyway? It's your fault.

Rather than simply accepting Google and Facebook's realities as untouchable, Taylor instead looks at what could to be done to improve the situation. She has three basic proposals:

- Include paid alternatives.

- Start defining data in more sophisticated ways.

- Develop new processes for handling content.

On the first, Taylor notes: "Many users are not concerned about what happens to their data, or accept it as part of the bargain in using a free platform. Others do care, and they should be offered some alternative – such as a limited opt-out or an option of a paid subscription – other than exclusion from services that are now becoming embedded in daily life."

It's not hard to imagine a Facebook Pro option that gives you back rights over how your data is used, requiring Facebook to delete it after a certain period of time, for example. It is hard to see Facebook offering this voluntarily, however. For one, it would have to put a dollar sign on everyone's head for what their personal information is worth to them – something that would put a spotlight on a topic that people go out of their way not to think too hard about.

Although it does raise the intriguing question: how much do you think it would be? $10 a month? $50 a year?

Defining data

Taylor's second point about data is probably the most important and interesting. She notes that everything that goes through the online giants is just data and treated the same regardless of whether it is a blog post meant to be read by as many people as possible or a private chat, highly personal and intended specifically for one person at one point in time.

When Facebook throws up an image of what you were doing three years ago, it can be delightful, reminding you unexpectedly of an event you have forgotten or not thought about for a while. But when it turned on the feature, users complained bitterly that pictures of lost love ones were suddenly appearing in their news feeds and shocking them. Facebook tweaked its settings, but the fact is that its systems are not set up to recognize intrinsically human understandings of information.

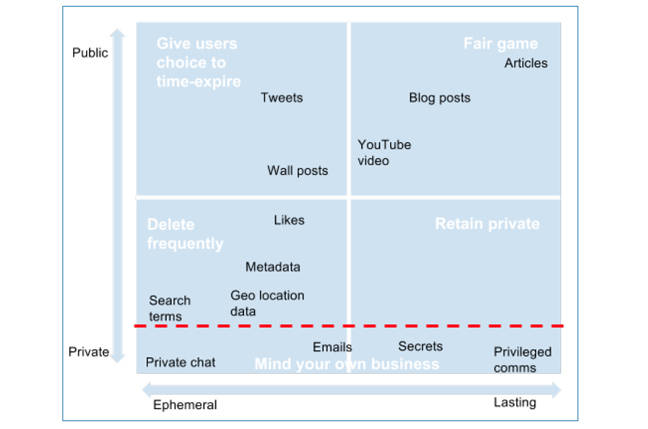

Taylor has produced a graphic demonstrating the different kinds of information that will pile into Google and Facebook, ranging from private to public and ephemeral to lasting. And she suggests that they need to be recognized and handled differently according to which type they are: blog posts retained and public; private chats invisible to the companies; geo location data deleted after a certain period of time.

A proposed model for fitting data into more human boxes

Arriving at a solution

And tying all this together is the concept that these new ways of viewing and handling the data given to their monolithic companies should be developed in open consultation with all those impacted: the companies themselves, the users, the advertisers and governments.

Nation states have an obligation to protect human rights. It's time they started doing so in relation to the online environment "rather than rely on ad hoc mediation of these rights by private companies."

Self-regulation should mean users being given more rights over their data, not the companies who profit from the data being allowed to do whatever they want so long as they don't break any laws.

And if anyone thinks that we can continue on as we have been, turning a blind eye to growing concerns and relying on private agreements between these companies and governments – particularly law enforcement – then Taylor points to the recent European Court of Justice decision against Facebook brought by Max Schrems.

The times they are a-changin; and it's time to get to pragmatics, Taylor argues. Her paper is a good start point for that conversation. ®