Original URL: https://www.theregister.com/2015/09/24/bbc_space_a_short_history_of_indoor_relief/

The BBC's Space: A short history of 21st Century indoor relief

Digital: the magic middle-class makework word

Posted in Legal, 24th September 2015 08:02 GMT

Special Report It was Open London last weekend, where for two days we got to see inside buildings normally closed to the public. With Doctor Who’s Tardis being unavailable, my kids found themselves on the Dazzle Ship moored in the Thames*.

They were at once accosted by someone showing them an app. Take a photo, slap it on your own Dazzle Ship, turn it into a 3D model and share it with others! Available on iPhone, iPad and Android! Two steps in, and they hadn’t yet seen a thing.

The app isn’t terrible, but given that the kids have been taking pictures using a phone or tablet and jazzing them up in funky filters since they were two, it didn’t give them anything new, either. They’re still at the age where they’re amazed by everything, and Dazzle Ships were such an odd idea it was hard to see how something interesting couldn’t be conveyed. Like: What was the idea behind it? How was this anti-camouflage supposed to work? Were they effective?

You know what kids are like – questions, questions, questions. But the app had no answers. That wasn’t the app designer’s brief. It never is: distraction is the point.

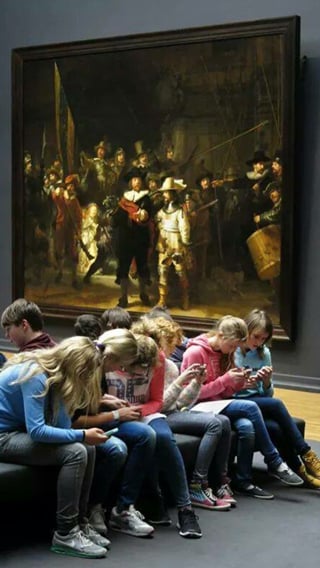

My experience is pretty common today. You can’t walk far into a museum or gallery without being showered in digital gimmicks. In this case, we got about a yard. Is there too much of this now? Is it even a good thing at all? Does the digital gimmickry distract you from the real experience? One popular picture circulating last year seemed to sum up such anxieties – the “kids ignoring Rembrandt” photo, showing teens tapping away at smartphones oblivious to Rembrandt’s painting The Night Watch.

This led to much hand-wringing, since there are some things you need to experience first-hand, not via a crappy digital thumbnail, and great paintings by old dead white guys are one of them. Unfair**, cried others: “Hey, analog Dads – leave the kids alone!” And the pic spawned this joke, which may not actually be a joke at all, but next year’s “digital engagement and inclusion strategy” at the Rijksmuseum.

Either way, it is hard to argue that today we have a shortage of digital gimmickry or even a shortage of digital art, with the taxpayer-funded institutions of the culture sector tipping millions into the cause of digital distraction. Nobody holding a purse of your money seems to be able to say "no" to an idea containing the word "digital", which has become a magic key to release funding which might otherwise be denied, if the idea was considered on its merits.

In fact, digital art is now so ubiquitous, defining it is as difficult as defining a digital startup or a digital business. For example, to big up its “digital cluster”, the government began to count chemists, public relations companies and even the Bank of England as digital businesses. Because almost all use modern communication tools or technology, they all must be digital.

Yesterday, the Daily Mail stumbled upon the phenomenon, without really realising it. In its quest to find skeletons in Alan Yentob’s enormous wardrobe, the paper discovered that the BBC created a digital arts quango, then chucked money at it. The BBC incubated the nebulous concept, chipping in half of the £16m funding for the new quango – and gave it the real committee-couldn’t-think-of-a-name name, "The Space".

Being an arts quango, money has gone on some nutty stuff: “a Gaelic birdsong video and Syrian puppet films”, the Mail told us. There’s a video wall (inevitably) and a bit of this:

There are also ideas which aren’t actually so bad, but which should really belong to existing BBC shows or services, such as the “John Peel record collection”. In reality, this is a playlist “curated” by an artist. It’s really somebody doing a guest spot on Radio 6 Music, only with a picture of the sleeve or disc. In the two years since launch, Space has managed to produce just four of these John Peel playlists, leaving us to wonder, why it couldn’t be done without the committees of digital arts bods hemming and hawing?

If this proves anything, it’s that “radio people” are hardworking and inventive (because they need to be) while digital people take a long time to do anything at all (because they can). Even posing the question of why John Peel record collection playlists are on Space, not 6 Music, is an interesting question to pursue, because it gets to the point (or lack of it) of funding a new digital arts quango.

Alan Yentob’s closet may contain a city-sized cemetery for all we know, but the BBC’s creative director is surely a red herring in this story. A better question is why Space exists at all. And we can only answer that by examining how it came about.

Indoor relief for the media classes: a brief history

Space has echoes of the Nathan Barley quango, memorably described by readers as “Welfare for Wankers” – albeit on a much less grand scale.

Back in the pre-recession New Labour era, around 2007, Ofcom wanted to expand its empire and create a taxpayer-funded commissioner of new media stuff, called the Public Service Publisher, or PSP. Ofcom had found (to nobody’s surprise) a dearth of “public sector content” on the internet. A mere £100m a year would do the trick, and fix this most pressing problem – surely by now on a par with migration, climate change or famine. Parliament later quashed the idea.

Space’s interim CEO is Anthony Lilley, one of the prime movers behind the PSP, who we interviewed here back in March 2007.

Around the same time as the PSP was being spawned, Channel 4 hired BBC tech worthy Tom Loosemore to head up a new media fund, 4IP. Like the PSP, 4IP vowed to “reinvent public service media for the digital age”. The ideas funded were remarkably similar too, including “a discussion tool... [a] question and platform, which allows the public to put their concerns to ministers and high-profile figures” – as if Twitter and email had never been invented. Three years and £50m later, 4IP was dissolved. Loosemore resurfaced at the Government Digital Service as its deputy director, where, amid staff allegations of nepotism and cabals, he was in a key position as the credibility of HM Government’s electronic publishing operation disappeared down the toilet, only to quit in the great stampede for the exit last August.

The PSP idea was revived last year by former No 10 SPAD Rohan Silva, who identified (once again) a “chronic funding gap in the UK for companies creating digital media content, as our venture capital funds do not typically invest in this sector”. But for once, a gravy train had rolled out of the station without Silva on board. He hadn't been paying attention: one was merrily commissioning away.

These ideas were conceived in happy, pre-austerity days. The concept had been snuffed out by Ofcom and Channel 4, but had taken root at the BBC, where austerity only ever happens to other people.

We must build... a giant digital trough

Writing at the BBC in 2007, new media luvvie Bill Thompson*** argued that although everybody appeared to be sharing digital media everywhere you looked, this was actually an illusion. The taxpayer needed to be tapped up once again. Why?

“The real problem with MySpace, YouTube and Flickr and the many other social spaces, sharing tools and online collaborative mechanisms is not that they are privately owned, it is that there is no public service ethos behind them.”

Undoubtedly so, but did anyone other than Thompson and a handful of new media freelancers actually care? Undeterred, he outlined a grandiose vision. There would be a new er, something: “This does not have to mean a state-owned online social network, although it could do,” Thompson mused, before setting his ambitions a little lower.

Thompson was hired by his friend and former Guardian digital boss Tony Ageh, who was by now in charge of the BBC's incomparable archive, and a plan was hatched. Remember, this was before The Crash, a time when the BBC was burning through £120m outlay on its Digital Media Initiative, called by one the execs the BBC's "digital brain”.

Bill Thompson. Pic: Cory Doctorow

Under the plan, the BBC would create a commissioning thing for digital media stuff, and so help save the internet. This is a classic expression of public sector narcissism, where the circular logic goes like this: Spending other people's money is what makes us virtuous. And we’re virtuous people, because we spend your money on things like this.

Ageh certainly showed signs of Noble Cause-itis when he described Space as a “higher calling for both the BBC and the Licence Fee”. Digital had become a kind of substitute religion; Minister Ageh and Minister Thompson were its evangelicals.

Yet the premise behind the plan was dubious and based on a fairly narrow and anti-humanist interpretation of developments in new media. When people complain about what’s wrong with the internet and what might make it better, it is unlikely that you will hear the words: “I simply can’t find anywhere to host or share my stuff. If only someone could start a photo-sharing social network!”

Sharing your photos on Flickr is not some underground samizdat activity. Digital media is characterised not by scarcity, but by ubiquity. As we’ve seen from time to time, what gets users riled isn’t the absence of a place to share stuff, but the terms on which individuals are required to share that stuff – and what’s subsequently done with that stuff. What’s under threat today isn’t some collective "space", but the gradual disenfranchisement of the individual from participating fully and exercising their legal and human rights on networks: specifically, the individual’s ability to own or control and maybe even trade their digital stuff.

State-owned, collectivised server farms

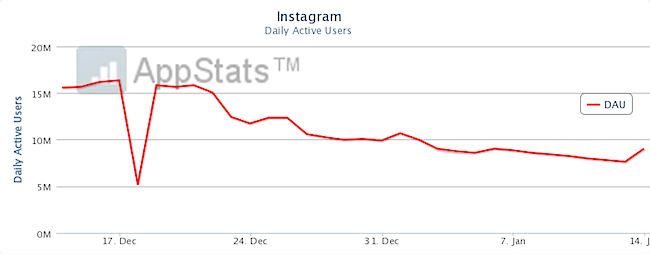

Ordinary people aren't stupid: they recognise when they’re being fleeced and react very strongly against it: whether its Instagram changing their T&Cs to assert more ownership or British bureaucrats trying to collectivise ownership of your property. Both are land grabs.

Instagram traffic backlash: People care more about their digital property than who owns the plantation

It’s the coercive transfer of property that they recognise and react more strongly against, not some ownership structure. And pointedly, readers didn't respond to state collectivisation positively, sighing with relief that the state had acquired ownership of their digital stuff. At all.

If you were to perform a “digital ethics audit”, the BBC doesn't emerge as one of the Good Guys, as Richard Hooper pointed out in his 2012 report for the government. The BBC routinely strips metadata from images that individuals send to the BBC, which Hooper pointed out is actually a criminal act. He also castigated it for not collaborating well with others on media formats.

So, trying to argue that the “public sphere was impoverished” using a definition of platform ownership is a bit like calling the Space Age "the Stone Age", because Neil Armstrong brought rocks back from the Moon. Of course you can try, but it isn’t really the full picture. It shows a tenuous, possibly utopian, grasp on reality.

The absence of “a public space” that, er, Space was supposed to fill did not actually mean “a space used by the public”, but “collectively owned”, in the Old Clause 4 of the Labour Party sense. But perhaps the ambiguity was intentional. Either way, it did the trick, and opened the BBC’s purse, and the idea was enthusiastically backed by the BBC Trust.

The Trust has a statutory role to see the BBC does its core job, but when it comes to anything digital, it tends to swoon like a giddy schoolgirl. The grander and vainer the digital proposal, the less critical was the BBC Trust. In 2011, the BBC Trust had described the doomed Digital Media Initiative as “something of which the BBC should be proud”. It was soon making the same swoony noises about Space.

What happened next?

The Space was announced as a formal collaboration with the Arts Council in 2012, which gave it a quasi-evangelical role in orienting other public sector organisations to doing web and apps, a "digital capacity-building" mission, as well as “connecting arts organisations with each other” (translation: networking, junkets). Here it took on a more Arts Council flavour, being a kind of digital portal for arts events****.

Not all audiences found their Space collaborations were a riotous success. “Given the size and reach of the BBC, we had hoped that the audience might have been larger and that a greater number would trickle through to our own website,” one participant noted. Interestingly, only 35 per cent of the arts orgs involved could identify a definite positive traffic impact on their sites from collaborating with the new quango. When audiences had the choice of going to the arts organisation's site or Space, they often shunned (PDF) the Space.

Naturally the theatres and museums were delighted with the helping hand. “89 per cent had ‘met’ or ‘strongly met’ their capacity-building objectives,” the Arts Council also noted (exec summary, pdf). “60 per cent reported changes in staff roles, giving greater prominence to digital.”

Yet merely conducting the evaluation of these modest pilots for the Space had created a mind-boggling amount of work. The Arts Council’s evaluation report drew on nine separate reports into traffic*****. The BBC had commissioned or funded five of these.

The Digital Trough

It’s too subtle for the Daily Mail to report, but there’s a story here, and it’s bigger than one about Syrian puppeteers and the paper’s ongoing obsession with Alan Yentob.

The British philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill once described the British Empire as "outdoor relief for the middle classes". The Victorians at the time were funding "indoor relief", a state-sponsored workhouse programme which invented jobs for the poor to prevent them being idle. Mill’s joke was that the Empire was a gigantic job creation scheme.

Today, “digital” has become the UK’s indoor relief program for the middle classes. Our digital do-gooders embark on a variety of Noble Causes, such as “teaching kids to code”, building “digital capacity” or hyping a "digital cluster", which are often responses to problems that don’t really exist. Sometimes – as we saw with the Government Digital Service (a quintessential digital-evangelical Mission) – the missionaries tout unique skills that don't really exist, but that can be used to bully and coerce.

The Space and the other now-abandoned "digital media commissioners" are a response to an imaginary scarcity, or an invented crisis, with the sketchy justification that the Cause was so Noble, no further justification was necessary. In the specific example of Space, the justification hinges on a definition of "public" that the public don't really care about. What they do care about is brushed aside.

What unites all these ventures – apart from the numinous word "digital" – is that administering them creates enormous amounts of work.

Our digital relief programmes today may even employ far more people than the British Empire employed in the Victorian era. From this estimate from the National Archives, the real number the Empire employed in the 19th Century is smaller than the 4,000 frequently cited. So while your kids doodle on a pointless arts app, or another "digital engagement" microsite goes dark, remember that at least the Victorians got some decent tea out of the deal. ®

Bootnotes

* It's actually an artistic homage to the Dazzle Ships applied to the former warship HMS President (1918), rather than a preserved Dazzle Ship.

** Or more charitably, you can only take so much of a good thing.

*** Here's Bill at The Register in 2002, busting net libertarian mythology with some gusto. From which we can infer that the flight from reality took place between 2002 and 2007, and may have coincided with a flight towards some work.

**** As of February this year, Ageh was still struggling to define the point of The Space. He devoted almost 5,000 words to a recent attempt before concluding it was "a higher calling".

***** Arts Council England, Artistic Assessments (January 2013); Arts Council England, Comprehensive Evaluation: Marketing and Communications for The Space pilot (2013); CogApp, The Space: User testing research (November 2012); eDigital Research, Pulse survey – website survey: Initial findings (August 2012) Independent evaluation of the pop-up Space user survey; Digital, The Space: Pilot analytics report (February 2013); Hassell Inclusion, User testing of The Space with disabled users (December 2012); MTM, Evaluation of The Space: Impact on Participants (February 2013); An independent evaluation of the impact of The Space programme on participating organisations; MTM, Evaluation of The Space: Artistic quality and innovation (December 2012); TrendSpot, The Space: Pulse evaluation deep dive (February 2013).